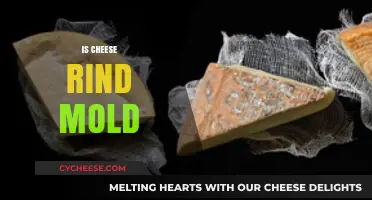

The claim that cheese is made from cow pus is a controversial and misleading statement that has sparked debates among consumers and experts alike. While it is true that some dairy products may contain trace amounts of somatic cells, commonly referred to as pus, from cows, it is essential to understand the context and the dairy production process. Somatic cells are naturally present in milk and can increase due to factors like mastitis, an inflammation of the udder, but strict regulations and quality control measures ensure that milk with elevated somatic cell counts is not used for human consumption. Cheese production involves curdling milk, separating curds from whey, and aging, which further reduces any potential presence of somatic cells. Therefore, the notion that cheese is primarily composed of cow pus is inaccurate and oversimplifies the complex dairy production process.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Claim | Cheese is made from cow pus. |

| Reality | False. Cheese is primarily made from milk, not pus. |

| Pus Definition | Pus is a thick, yellowish-white liquid composed of white blood cells, dead tissue, and bacteria, typically found in infected wounds or abscesses. |

| Milk Composition | Milk is a natural secretion from mammary glands, containing water, fats, proteins (casein, whey), lactose, vitamins, and minerals. |

| Cheese Production | Cheese is made by curdling milk (often with rennet or acids), separating curds from whey, and aging the curds. |

| Source of Misinformation | Misinterpretation of dairy farming practices or confusion between milk and pus. |

| Health Impact | Cheese made from properly sourced milk is safe and nutritious. Pus in milk would indicate infection and render it unsafe for consumption. |

| Regulations | Dairy industries are regulated to ensure milk is free from contaminants, including pus. |

| Scientific Consensus | There is no scientific evidence supporting the claim that cheese is made from cow pus. |

| Common Misconception | The misconception may stem from misinformation about dairy farming or sensationalized claims. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Myth vs. Reality: Clarifying misconceptions about cheese production and its relation to cow pus

- Milk Composition: Understanding natural enzymes and cells in milk, not pus

- Cheese-Making Process: How milk is transformed into cheese, debunking pus claims

- Health Implications: Addressing safety and nutritional value of cheese consumption

- Industry Standards: Regulations ensuring cheese is free from harmful substances like pus

Myth vs. Reality: Clarifying misconceptions about cheese production and its relation to cow pus

Cheese, a beloved staple in diets worldwide, often falls victim to misconceptions, one of the most persistent being its alleged connection to cow pus. This myth stems from a misunderstanding of dairy farming practices and the natural processes involved in cheese production. Let’s dissect this claim by examining the realities of milk production, the role of somatic cells, and the stringent regulations that ensure cheese safety.

Understanding Somatic Cells in Milk

Milk naturally contains somatic cells, which are primarily white blood cells (leukocytes) and epithelial cells shed from the lining of the udder. These cells are present in all mammals, including humans, and their presence is a normal part of milk composition. The myth of "cow pus" arises from conflating elevated somatic cell counts (SCC) with pus, a thick, yellowish fluid associated with infection. While high SCC levels can indicate mastitis (udder inflammation), regulatory standards strictly limit the amount of somatic cells in milk used for cheese production. For example, in the U.S., milk with SCC exceeding 750,000 cells/mL is typically rejected for human consumption. This ensures that milk used for cheese is of high quality and free from contamination.

The Role of Pasteurization and Cheese-Making

Pasteurization, a critical step in modern dairy processing, further safeguards cheese production. This heat treatment eliminates harmful bacteria and reduces somatic cell counts, ensuring the final product is safe and wholesome. Artisanal cheeses made from raw milk, though less common, are subject to rigorous testing and aging processes that naturally eliminate pathogens. During cheese-making, milk is coagulated, and the curds are separated from the whey, which contains most of the somatic cells. This process inherently minimizes any residual cell content, making the "cow pus" claim biologically implausible.

Comparing Cheese to Other Dairy Products

To put this myth in perspective, consider other dairy products. Butter, yogurt, and even ice cream are made from the same milk used for cheese, yet they rarely face similar scrutiny. The focus on cheese likely stems from its solid, textured nature, which some mistakenly associate with impurities. However, cheese’s transformation from milk involves precise fermentation and aging, processes that enhance flavor and safety, not compromise them. For instance, aged cheeses like cheddar or Parmesan undergo months of maturation, during which any trace of somatic cells becomes negligible.

Practical Tips for Informed Consumption

For consumers concerned about cheese quality, understanding labels is key. Look for certifications like "organic" or "grass-fed," which often indicate lower somatic cell counts due to stricter animal welfare practices. Additionally, aged cheeses are inherently safer due to their extended production process. If you’re still unsure, opt for pasteurized varieties, which are widely available and meet stringent safety standards. Finally, educate yourself on dairy farming practices—many farms now use advanced technology to monitor cow health and milk quality, ensuring the milk used for cheese is pristine.

In conclusion, the notion that cheese contains cow pus is a myth rooted in misinformation. By understanding the science of milk composition, the safeguards in cheese production, and the regulatory frameworks in place, consumers can confidently enjoy cheese as a safe and nutritious food. The next time you savor a slice of cheddar or sprinkle Parmesan on your pasta, rest assured: it’s the product of careful craftsmanship, not misinformation.

Is Cheese a Dry Ingredient? Unraveling the Culinary Mystery

You may want to see also

Milk Composition: Understanding natural enzymes and cells in milk, not pus

Milk, a staple in diets worldwide, is a complex biological fluid designed to nourish the young of mammals. Its composition is a delicate balance of nutrients, enzymes, and cells, each serving a specific purpose. One common misconception is that cheese, derived from milk, contains cow pus. To address this, let's dissect milk’s natural components: enzymes and somatic cells. These elements are not indicators of contamination but rather essential parts of milk’s biological function. For instance, enzymes like lactoperoxidase act as natural preservatives, protecting milk from bacterial growth. Somatic cells, primarily white blood cells, are present in trace amounts and reflect the cow’s health, not the presence of pus. Understanding these components is crucial for separating myth from science.

Analyzing milk composition reveals a precise structure tailored for nutrition and protection. Milk contains approximately 87% water, 3.8% fat, 3.3% protein, and 4.6% lactose, alongside vitamins, minerals, and enzymes. Enzymes such as lipase and proteases aid in digestion, breaking down fats and proteins into absorbable forms. Somatic cells, typically ranging from 100,000 to 200,000 per milliliter in healthy cows, are part of the immune system, not pus. Pus, a product of infection, contains high levels of dead neutrophils, bacteria, and tissue debris, which are absent in properly sourced milk. Regulatory standards ensure somatic cell counts remain low, with the USDA limiting counts to 750,000 cells/mL for Grade A milk. This distinction is vital for debunking the "pus in cheese" myth.

To illustrate the difference, consider the cheese-making process. Coagulation, the first step, relies on enzymes like rennet or bacterial cultures to curdle milk. These enzymes interact with milk proteins, not somatic cells or contaminants. During aging, beneficial bacteria further transform the curd, enhancing flavor and texture. Pus, if present, would introduce harmful pathogens and alter the cheese’s structure, making it unsafe for consumption. Practical tip: When purchasing dairy, check labels for somatic cell counts or organic certifications, which often indicate lower cell counts and stricter health standards for cows.

Persuasively, the "pus in cheese" claim oversimplifies milk’s biology and ignores regulatory safeguards. While somatic cells are present, they are not pus and do not compromise milk quality when within acceptable limits. Cheese, as a processed dairy product, undergoes rigorous filtration and fermentation, eliminating potential contaminants. Comparative studies show that somatic cells in milk are analogous to white blood cells in human breast milk, both serving protective roles. For those concerned, opting for pasteurized or ultra-pasteurized dairy ensures further reduction of cell counts and enzymes, though this may alter flavor profiles.

In conclusion, milk’s natural enzymes and somatic cells are not pus but integral components of its biological design. Cheese production leverages these elements, not contaminants, to create a safe and nutritious food. By understanding milk composition and regulatory standards, consumers can confidently enjoy dairy products without misinformation-driven concerns. Practical takeaway: Educate yourself on dairy labels and processing methods to make informed choices, ensuring both quality and peace of mind.

Mastering the Art of Crafting the Perfect Ham and Cheese Sandwich

You may want to see also

Cheese-Making Process: How milk is transformed into cheese, debunking pus claims

Milk, a nutrient-rich liquid, undergoes a remarkable transformation into cheese through a series of carefully controlled steps. The process begins with coagulation, where enzymes or acids are added to milk, causing it to curdle. This separates the milk into solid curds (the foundation of cheese) and liquid whey. Contrary to the myth that cheese contains cow pus, this step involves no foreign substances—only natural or microbial agents like rennet or lactic acid bacteria. These agents mimic the stomach’s digestive process, breaking down milk proteins in a way that’s entirely food-safe and intentional.

Next, the cutting and heating phase refines the curds. The curd mass is cut into smaller pieces to release more whey, then gently heated to expel moisture and firm the texture. This step is crucial for determining the cheese’s final consistency, from soft and creamy to hard and crumbly. Importantly, no pus or abnormal substances are introduced here; the focus is on manipulating milk’s inherent components—proteins, fats, and water—through temperature and mechanical action.

Aging and ripening further develop flavor and texture. During this stage, cheeses are stored under specific conditions (temperature, humidity) to allow beneficial bacteria and molds to work. For example, cheddar ages for 2–24 months, while brie ripens in 4–8 weeks. Claims linking this process to pus are baseless; the visible eyes in cheeses like Swiss or the molds in blue cheese are naturally occurring and part of the intended transformation, not signs of contamination.

To debunk the pus myth entirely, consider this: pus is a product of infection, containing white blood cells, dead tissue, and bacteria. Milk, however, is tested rigorously for somatic cell counts (SCC), which indicate udder health. In the U.S., milk with SCC above 750,000 cells/mL (indicating possible infection) is rejected for human consumption. Even in healthy cows, SCC averages 200,000 cells/mL—far below levels suggesting pus. Cheese is made from milk that meets strict safety standards, ensuring no pus is present.

In summary, the cheese-making process is a precise art rooted in science, transforming milk through coagulation, heating, and aging. Each step builds on milk’s natural properties, with no room for pus or contaminants. Understanding this process not only dispels myths but also deepens appreciation for the craftsmanship behind every wheel, block, or slice of cheese.

Spicy Delight: Exploring Mexico's Green Chili and Cheese Dish

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Health Implications: Addressing safety and nutritional value of cheese consumption

Cheese, a staple in diets worldwide, often faces scrutiny over its origins and health implications. The claim that cheese contains cow pus stems from the presence of somatic cells, which can include white blood cells, in milk. While it’s true that elevated somatic cell counts may indicate mastitis in cows, regulated dairy industries enforce strict limits to ensure milk safety. For instance, the FDA permits up to 750,000 somatic cells per milliliter in milk, a threshold well below levels harmful to human health. This regulatory oversight minimizes risks, but it’s essential to understand the broader health context of cheese consumption.

From a nutritional standpoint, cheese is a dense source of protein, calcium, vitamin B12, and phosphorus, making it a valuable addition to diets, particularly for children, adolescents, and older adults. A single ounce of cheddar, for example, provides over 20% of the daily calcium requirement for adults aged 19–50. However, its high saturated fat and sodium content necessitates moderation. The American Heart Association recommends limiting saturated fat to 5–6% of daily calories, meaning a 2,000-calorie diet should include no more than 13 grams of saturated fat daily. A practical tip: opt for low-fat or part-skim varieties like mozzarella or Swiss to balance nutritional benefits with health risks.

Safety concerns arise primarily from unpasteurized (raw) cheese, which can harbor pathogens such as Listeria, E. coli, and Salmonella. Pregnant women, young children, older adults, and immunocompromised individuals are particularly vulnerable. For instance, Listeria infection during pregnancy can lead to miscarriage, stillbirth, or severe neonatal illness. Pasteurization eliminates these risks, making it a critical step in cheese production. Always check labels for pasteurization, especially when consuming soft cheeses like Brie or Camembert, which are more likely to be produced raw.

Comparatively, the alleged presence of "cow pus" pales in significance to the well-documented risks of excessive cheese consumption, such as cardiovascular disease and hypertension. A 2018 study in the *European Journal of Nutrition* found that while moderate cheese intake (up to 40 grams daily) correlated with reduced heart disease risk, higher consumption increased LDL cholesterol levels. To mitigate this, pair cheese with fiber-rich foods like whole-grain crackers or fresh vegetables, which can help offset its fat content. Additionally, consider portion control: a serving size is typically 1.5 ounces, roughly the size of a lipstick tube.

In conclusion, while the "cow pus" claim is technically rooted in the presence of somatic cells, it’s a misleading oversimplification of cheese’s safety profile. The real health considerations lie in its nutritional density, potential pathogen risks in raw varieties, and the need for moderation due to saturated fat and sodium. By choosing pasteurized, low-fat options and adhering to recommended serving sizes, individuals can enjoy cheese as part of a balanced diet without undue concern. Always consult a healthcare provider or dietitian for personalized advice, especially for those with specific health conditions or dietary restrictions.

Does Cheese Contain Vinegar? Unraveling the Ingredients in Your Favorite Dairy

You may want to see also

Industry Standards: Regulations ensuring cheese is free from harmful substances like pus

Cheese production is governed by stringent industry standards designed to ensure consumer safety and product quality. One critical aspect of these regulations is the prevention of harmful substances, including the oft-misunderstood concept of "cow pus," from entering the final product. While the term "pus" is sensationalized in some discussions, it refers to somatic cells—primarily white blood cells—that can be present in milk due to mastitis, an inflammation of the udder. Regulatory bodies worldwide set clear limits on somatic cell counts (SCC) to mitigate risks. For instance, the European Union mandates that raw milk used for cheese production must not exceed 400,000 cells/mL, while the U.S. FDA allows up to 750,000 cells/mL for fluid milk. These thresholds are based on scientific research linking high SCC to potential health risks and reduced milk quality.

To comply with these standards, dairy farmers implement rigorous practices. Regular udder health checks, hygienic milking procedures, and immediate treatment of infected cows are essential steps. Milk is also tested upon collection, and batches exceeding SCC limits are discarded or diverted for non-food purposes. For cheese makers, pasteurization—a process that heats milk to 72°C (161°F) for 15 seconds—effectively eliminates somatic cells and pathogens, further ensuring safety. However, raw milk cheeses, which bypass pasteurization, must adhere to even stricter SCC limits to minimize risk. Consumers can look for certifications like the USDA Organic or EU Organic labels, which often imply lower SCC due to their emphasis on animal welfare and preventive health measures.

The role of regulatory agencies extends beyond setting limits to enforcing them through inspections and penalties. In the U.S., the FDA and state departments conduct routine audits of dairy farms and processing facilities, while the EU’s Directorate-General for Health and Food Safety oversees compliance across member states. These agencies also collaborate with international bodies like the Codex Alimentarius to harmonize standards, ensuring that imported cheeses meet equivalent safety criteria. For example, cheeses entering the EU must comply with Regulation (EC) No 853/2004, which includes specific provisions for somatic cell counts and microbial contamination.

Despite these safeguards, misconceptions persist, fueled by misinformation and a lack of public awareness. Educating consumers about the science behind these regulations can bridge the gap between perception and reality. For instance, explaining that somatic cells are a natural component of milk, not an additive, and that their presence is carefully monitored, can alleviate concerns. Additionally, transparent labeling—such as indicating pasteurization status or SCC levels—empowers consumers to make informed choices. Practical tips for consumers include purchasing cheese from reputable sources, checking for certification logos, and storing products properly to prevent spoilage.

In conclusion, industry standards and regulations form a robust framework to ensure cheese is free from harmful substances, including elevated levels of somatic cells. By combining scientific thresholds, farmer diligence, and regulatory oversight, these measures protect public health while maintaining product integrity. As consumers, understanding these processes fosters trust in the dairy industry and allows us to enjoy cheese without unwarranted fears.

Is Arla Bread Spread Cheese? Unraveling the Dairy Mystery

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, cheese is not made from cow pus. Cheese is primarily made from milk, which is a natural secretion produced by cows and other mammals to nourish their young. Pus is a completely different substance associated with infection or inflammation.

Cheese may contain trace amounts of somatic cells (often referred to as "pus cells"), which are naturally present in milk. However, these cells are not pus and are not indicative of infection. Regulatory standards limit the number of somatic cells in milk used for cheese production to ensure safety and quality.

The claim often stems from misinformation or a misunderstanding of somatic cells in milk. Somatic cells are white blood cells and other cells shed from the udder lining, not pus. Critics sometimes use this to argue against dairy consumption, but it’s important to distinguish between somatic cells and actual pus.

Yes, it is safe to eat cheese made from milk containing somatic cells within regulatory limits. High levels of somatic cells can indicate poor milk quality or udder health issues, but milk used for cheese production must meet strict standards to ensure it is safe and wholesome for consumption.