Cheese is often described as spoiled milk, but this characterization oversimplifies the intricate process of cheese-making. While it’s true that cheese begins with milk that has undergone bacterial fermentation, this transformation is deliberate and controlled, not a result of spoilage. During cheese production, specific bacteria and enzymes are introduced to curdle the milk, separating it into curds and whey. The curds are then aged, pressed, and treated in various ways to develop flavor, texture, and preservation. This process turns what could be considered spoiled milk into a diverse array of cheeses, each with its unique characteristics. Thus, cheese is not merely spoiled milk but a carefully crafted product that highlights the art and science of fermentation.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Cheese is a dairy product made from milk, but it is not simply spoiled milk. It is produced through a controlled process of curdling milk using enzymes (like rennet) or acids, followed by draining, pressing, and aging. |

| Spoilage vs. Fermentation | Spoiled milk is milk that has undergone uncontrolled bacterial growth, leading to off flavors, odors, and textures. Cheese, on the other hand, involves deliberate fermentation by specific bacteria and molds, transforming milk into a stable, flavorful product. |

| Microbial Activity | Spoiled milk contains harmful bacteria that make it unsafe to consume. Cheese production uses beneficial bacteria and molds that break down milk components, creating unique flavors and textures while preserving the product. |

| Texture and Appearance | Spoiled milk becomes lumpy, curdled, and unappetizing. Cheese has a wide range of textures (soft, hard, creamy, crumbly) and appearances, depending on the type and aging process. |

| Shelf Life | Spoiled milk has a short shelf life and must be discarded. Cheese, when properly made and stored, can last from weeks to years, depending on the type. |

| Nutritional Value | Spoiled milk loses its nutritional value and can be harmful. Cheese retains and concentrates many nutrients from milk, such as protein, calcium, and vitamins. |

| Flavor Profile | Spoiled milk has an unpleasant, sour taste. Cheese has diverse flavor profiles, ranging from mild and creamy to sharp and pungent, depending on the production method and aging. |

| Safety | Spoiled milk is unsafe to consume due to harmful bacteria. Cheese is safe to eat when produced under hygienic conditions and properly aged, as the fermentation process inhibits pathogenic bacteria. |

| Purpose | Spoiled milk is a waste product. Cheese is a valued food item with cultural, culinary, and economic significance worldwide. |

Explore related products

$8.99 $9.99

What You'll Learn

- What is spoilage Understanding the natural process of milk spoiling and its transformation?

- Cheese-making basics: How controlled spoilage creates cheese through fermentation and bacteria

- Types of cheese: Exploring varieties made from different spoilage methods and cultures

- Safety concerns: Is spoiled milk in cheese safe to consume Health implications

- Taste and texture: How spoilage affects cheese flavor, aroma, and mouthfeel

What is spoilage? Understanding the natural process of milk spoiling and its transformation

Milk spoilage is a natural process driven by microbial activity and chemical changes. When milk is exposed to air, light, or warmth, bacteria—both naturally present and from the environment—begin to multiply. These microorganisms break down lactose (milk sugar) into lactic acid, lowering the pH and causing proteins to curdle. This results in the familiar signs of spoilage: a sour smell, thickened texture, and off-flavor. Unlike cheese, which harnesses controlled spoilage for preservation and flavor, spoiled milk is unsafe to consume due to potential pathogens like *E. coli* or *Salmonella*. Understanding this process highlights the difference between intentional fermentation and unintended decay.

To observe spoilage firsthand, leave a small amount of pasteurized milk at room temperature (20–25°C) for 24–48 hours. Note the changes: within 12 hours, a faint sour odor develops; by 24 hours, the milk separates into curds and whey; by 48 hours, mold may appear. This experiment illustrates how temperature accelerates bacterial growth—a key factor in both spoilage and cheese-making. While cheese relies on specific bacteria and molds to transform milk into a stable, flavorful product, uncontrolled spoilage lacks this precision, leading to waste or illness.

From a practical standpoint, preventing milk spoilage involves slowing microbial activity. Store milk at 4°C or below, as refrigeration reduces bacterial growth by 90%. Use airtight containers to limit oxygen exposure, and avoid returning unused milk to the carton to prevent cross-contamination. For extended preservation, pasteurization (heating to 72°C for 15 seconds) kills most spoilage bacteria, while ultra-high temperature (UHT) treatment (135°C for 1–2 seconds) allows milk to remain shelf-stable for months. These methods contrast with cheese-making, where bacteria are not eliminated but carefully managed.

Comparing spoiled milk to cheese reveals a critical distinction: intent. Spoilage is an accidental, uncontrolled process, while cheese-making is deliberate, guided by specific cultures, temperature, and time. For example, cheddar relies on *Lactococcus lactis* to acidify milk, while blue cheese uses *Penicillium roqueforti* for its distinctive veins. Both involve spoilage organisms, but in cheese, these are selected and monitored to create a safe, desirable product. Spoiled milk, however, is a byproduct of neglect, lacking the precision that transforms decay into delicacy.

In essence, spoilage is milk’s natural response to its environment, a process that can be harnessed or halted depending on human intervention. While spoiled milk is a sign of degradation, cheese exemplifies how controlled spoilage can preserve and enhance food. By understanding the science behind both, we can better appreciate the art of fermentation and the importance of proper storage. Whether you’re discarding curdled milk or savoring a slice of aged cheddar, the line between spoilage and transformation is thinner—and more fascinating—than it seems.

Exploring the Syllable Count in the Word Cheese: A Linguistic Breakdown

You may want to see also

Cheese-making basics: How controlled spoilage creates cheese through fermentation and bacteria

Cheese is, in essence, controlled spoilage of milk. This transformation relies on the deliberate introduction of bacteria and enzymes to ferment lactose into lactic acid, a process that lowers pH and curdles milk proteins. Unlike uncontrolled spoilage, which leads to decay, cheese-making harnesses specific microorganisms to create a stable, edible product. For instance, starter cultures like *Lactococcus lactis* are added in precise amounts—typically 1-2% of milk volume—to initiate fermentation. This step is critical: too little culture results in slow curdling, while too much can produce excessive acidity, ruining texture.

The role of bacteria in cheese-making extends beyond curdling. As fermentation progresses, these microorganisms produce flavor compounds, such as diacetyl (buttery notes) and acetoin (sweet, creamy undertones). In aged cheeses like Cheddar, bacteria continue to metabolize lactose remnants, contributing to sharper flavors over time. Meanwhile, molds like *Penicillium camemberti* in Camembert or *Penicillium roqueforti* in blue cheese introduce enzymes that break down fats and proteins, creating distinct textures and aromas. Each cheese variety requires a tailored bacterial or fungal profile, emphasizing the precision of this controlled spoilage.

Temperature and humidity are as crucial as microbial selection. For example, soft cheeses like Brie ferment at 20-24°C (68-75°F) with high humidity to encourage mold growth, while hard cheeses like Parmesan require higher temperatures (35-40°C or 95-104°F) to expel moisture and firm up curds. Salt is another key player, applied in concentrations of 1-3% by weight to inhibit unwanted bacteria and enhance flavor. These conditions must be monitored rigorously, as deviations can lead to off-flavors or unsafe products. Think of cheese-making as a symphony: each element—bacteria, temperature, salt—plays a specific role, and the conductor ensures harmony.

Aging is where controlled spoilage truly shines. During this phase, bacteria and molds continue to transform the cheese, breaking down proteins and fats into complex molecules that deepen flavor and improve texture. For instance, a young Gouda aged 1-6 months develops a mild, nutty profile, while a 2-year-old Gouda becomes harder and more caramelized due to ongoing enzymatic activity. Home cheese-makers can experiment with aging by maintaining a consistent environment—a wine fridge set to 10-13°C (50-55°F) with 85% humidity works well for most varieties. Patience is key, as rushing the process yields inferior results.

Understanding cheese as controlled spoilage demystifies its creation and highlights the artistry behind it. By manipulating bacteria, temperature, and time, cheese-makers transform a perishable liquid into a durable, flavorful solid. This process is not just science; it’s a craft that balances precision with creativity. Whether you’re a home enthusiast or a professional, mastering these basics opens the door to endless possibilities—from creamy Bries to crumbly fetas. After all, cheese is proof that sometimes, a little spoilage goes a long way.

Top Healthy Low-Fat Cheese Options for Delicious Sandwiches

You may want to see also

Types of cheese: Exploring varieties made from different spoilage methods and cultures

Cheese is, indeed, a product of controlled milk spoilage, but the methods and cultures used transform it into a culinary treasure rather than a waste. The diversity in cheese varieties arises from the intricate interplay of spoilage techniques, microbial cultures, and aging processes. Each method imparts distinct flavors, textures, and aromas, creating a spectrum of cheeses that cater to every palate.

Consider the role of lactic acid bacteria in fresh cheeses like cottage cheese or queso fresco. These cheeses rely on a simple fermentation process where bacteria convert lactose into lactic acid, causing milk to curdle. The result is a mild, tangy flavor and a soft, crumbly texture. This method is quick, often taking just a few hours, and requires minimal equipment, making it accessible for home cheesemakers. For optimal results, maintain a fermentation temperature of 72–75°F (22–24°C) and use a mesophilic starter culture for consistent acidity.

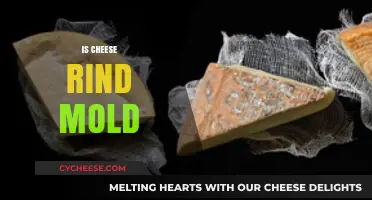

In contrast, mold-ripened cheeses like Brie or Camembert showcase a different spoilage method. Here, *Penicillium camemberti* is introduced to the cheese's surface, creating a velvety rind and a creamy interior. The mold breaks down proteins and fats, producing earthy, nutty flavors. Aging these cheeses for 3–4 weeks in a humid environment (around 90% humidity) is crucial, as it allows the mold to flourish and develop the desired texture. Be cautious: improper humidity can lead to dry rinds or excessive ammonia flavors.

Blue cheeses, such as Stilton or Gorgonzola, take spoilage a step further by introducing *Penicillium roqueforti* directly into the curd. This mold grows internally, creating veins of intense, pungent flavor. The cheese is pierced during aging to allow air exposure, fostering mold growth. Aging times vary—Stilton matures for 9–12 weeks, while Gorgonzola can take 2–3 months. For enthusiasts, experimenting with piercing frequency can alter the intensity of the veining and flavor profile.

Finally, washed-rind cheeses like Époisses or Limburger demonstrate how bacteria and brine can transform spoilage into sophistication. These cheeses are regularly washed with solutions like saltwater, wine, or beer, encouraging the growth of *Brevibacterium linens*. This bacterium produces a sticky, orange rind and a robust, savory flavor. The washing process must be consistent—typically every 2–3 days—to prevent unwanted mold growth. These cheeses are not for the faint of heart but offer a rewarding exploration of bold flavors.

Understanding these spoilage methods and cultures not only deepens appreciation for cheese but also empowers experimentation. Whether crafting a simple cottage cheese or aging a complex blue, the art lies in controlling the very processes that, left unchecked, would spoil milk. Each cheese tells a story of microbial mastery, turning potential waste into a delicacy.

Is Cheese a TCS Food? Understanding Time-Temperature Control Requirements

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Safety concerns: Is spoiled milk in cheese safe to consume? Health implications

Spoiled milk, characterized by its sour smell and curdled texture, is generally considered unsafe for consumption due to the risk of bacterial growth, including pathogens like *Salmonella* and *E. coli*. However, cheese is a deliberate product of controlled milk spoilage, where specific bacteria and molds transform milk into a stable, edible form. The key difference lies in the process: spoilage in milk is uncontrolled and unpredictable, while cheese-making is a precise fermentation guided by specific cultures and conditions. This distinction raises the question: does the transformation of spoiled milk into cheese eliminate safety concerns, or are there still health implications to consider?

From an analytical perspective, the safety of cheese hinges on the type of bacteria involved and the conditions during production. In cheese-making, lactic acid bacteria (such as *Lactococcus* and *Streptococcus*) dominate, creating an acidic environment that inhibits harmful pathogens. For example, hard cheeses like cheddar undergo aging, which further reduces moisture content and makes it inhospitable for most bacteria. However, soft cheeses, particularly those made with raw milk, carry a higher risk of contamination from pathogens like *Listeria*. Pregnant women, the elderly, and immunocompromised individuals are advised to avoid unpasteurized soft cheeses due to the potential for severe health complications, including listeriosis.

Instructively, consumers can minimize risks by understanding labels and storage practices. Pasteurized cheeses are safer because the heat treatment kills harmful bacteria, while raw milk cheeses retain a higher risk profile. Proper storage is critical: hard cheeses should be wrapped in wax or parchment paper and stored below 40°F (4°C), while soft cheeses require airtight containers and should be consumed within a week of opening. For instance, leaving cheese at room temperature for more than two hours can accelerate bacterial growth, even in aged varieties. Following these guidelines ensures that the controlled "spoilage" in cheese remains safe for consumption.

Comparatively, the health implications of consuming cheese versus spoiled milk differ significantly. Spoiled milk can cause immediate gastrointestinal distress, such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, due to the presence of toxins produced by bacteria. Cheese, on the other hand, is generally well-tolerated because the fermentation process breaks down lactose and reduces the presence of harmful bacteria. However, excessive consumption of certain cheeses can lead to other issues, such as high sodium intake (e.g., feta contains up to 300 mg of sodium per ounce) or saturated fats, which contribute to cardiovascular risks. Moderation and awareness of individual health conditions are essential when incorporating cheese into the diet.

Descriptively, the transformation of milk into cheese is a marvel of microbiology, turning potential waste into a nutrient-dense food. The tangy flavor of cheddar, the creamy texture of brie, and the sharp bite of blue cheese all result from controlled spoilage processes. Yet, this transformation is not without risks. For example, artisanal cheeses made in small batches may lack the rigorous quality control of industrial producers, increasing the likelihood of contamination. Consumers should prioritize purchasing cheese from reputable sources and inspecting for signs of spoilage, such as mold outside the typical veining or an off-putting odor. By understanding the science and risks, one can appreciate cheese as a safe, spoiled milk product when handled correctly.

Is Cheese Overly Processed? Uncovering the Truth Behind Your Favorite Dairy

You may want to see also

Taste and texture: How spoilage affects cheese flavor, aroma, and mouthfeel

Cheese is, in essence, controlled spoilage of milk. This transformation hinges on microorganisms and enzymes breaking down milk’s proteins and fats, creating a spectrum of flavors, aromas, and textures. Spoilage, however, is a double-edged sword. While intentional spoilage by specific bacteria and molds crafts the desired characteristics of cheese, unintended spoilage—often from unwanted microorganisms—can distort these qualities. Understanding this distinction is key to appreciating how spoilage shapes cheese’s sensory profile.

Consider the role of bacteria in flavor development. Desirable spoilage, such as that caused by *Penicillium camemberti* in Camembert, produces earthy, nutty notes and a creamy texture. Undesirable spoilage, like *Clostridium* contamination, can introduce rancid, putrid flavors and a slimy mouthfeel. The difference lies in the type of microorganisms and their metabolic byproducts. For instance, lactic acid bacteria produce mild, tangy flavors, while coliform bacteria create off-putting aromas. Dosage matters too: even beneficial bacteria, in excess, can overwhelm the cheese’s intended profile.

Texture is equally affected by spoilage. Proteolytic enzymes break down milk proteins, contributing to the smooth, melt-in-your-mouth quality of aged cheeses like Gruyère. However, unchecked enzymatic activity, often from improper aging or contamination, can lead to an overly soft or crumbly texture. Lipases, enzymes that break down fats, add complexity but can turn sharp and soapy if overactive. Practical tip: monitor humidity and temperature during aging to control enzyme activity and preserve desired texture.

Aroma is perhaps the most volatile aspect of cheese, influenced by both microbial activity and chemical reactions. Desirable spoilage produces volatile compounds like diacetyl, responsible for the buttery scent of Gouda. Undesirable spoilage, such as from yeast overgrowth, can introduce yeasty or alcoholic aromas. Comparative analysis shows that while a hint of ammonia in aged cheeses like Parmesan is acceptable, excessive ammonia indicates improper aging or contamination. To mitigate this, ensure proper ventilation during aging and avoid cross-contamination with other foods.

Finally, mouthfeel—the tactile sensation of cheese—is a culmination of texture, moisture content, and fat distribution. Controlled spoilage creates a balanced interplay of creaminess and firmness, as seen in Brie. Uncontrolled spoilage, however, can result in a greasy or grainy mouthfeel. For home cheesemakers, maintaining consistent pH levels during curdling and pressing is critical. Aim for a pH of 4.6–5.0 for most cheeses to ensure proper coagulation and moisture retention.

In summary, spoilage is both the architect and the saboteur of cheese’s sensory qualities. By understanding the mechanisms behind flavor, aroma, and texture, one can navigate the fine line between desirable transformation and undesirable degradation. Whether crafting cheese or selecting it, this knowledge empowers a deeper appreciation of its complexity.

Cheese and Antibiotics: Unraveling the Myth of Dairy's Impact

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Cheese is not spoiled milk; it is a controlled transformation of milk through the process of curdling, separating curds from whey, and aging. This process preserves and enhances the milk rather than spoiling it.

Cheese is made by adding bacteria or enzymes (like rennet) to milk, causing it to curdle. The curds are then separated from the whey, pressed, and aged, creating the texture and flavor of cheese.

While cheese can spoil if not stored properly, it has a longer shelf life than milk due to its lower moisture content and the aging process, which inhibits bacterial growth.

Yes, cheese is safe to eat as long as it’s made and stored correctly. The cheesemaking process transforms milk into a stable, edible product, and proper storage prevents spoilage.