Dairy cheese is a beloved and versatile food product made from the milk of various animals, most commonly cows, goats, and sheep. It is produced through a process of curdling milk, separating the solids (curds) from the liquid (whey), and then pressing and aging the curds to develop flavor and texture. Dairy cheese comes in a wide range of varieties, from soft and creamy Brie to hard and sharp Cheddar, each with its own unique characteristics shaped by factors like milk type, bacterial cultures, and aging methods. As a staple in many cuisines worldwide, dairy cheese is not only prized for its rich taste but also for its nutritional value, providing essential nutrients such as protein, calcium, and vitamins. However, its classification as a dairy product has sparked debates, particularly in the context of dietary restrictions, lactose intolerance, and the rise of plant-based alternatives, raising questions about what defines dairy and whether all cheeses fit neatly into this category.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Types of Dairy Cheese: Cheddar, mozzarella, gouda, brie, and feta are popular varieties

- Cheese-Making Process: Curdling milk, separating whey, pressing curds, and aging

- Nutritional Value: High in protein, calcium, fat, and vitamins A and B12

- Lactose Content: Most aged cheeses have low lactose due to fermentation

- Health Considerations: Benefits and risks for digestion, heart health, and allergies

Types of Dairy Cheese: Cheddar, mozzarella, gouda, brie, and feta are popular varieties

Dairy cheese is a cornerstone of culinary traditions worldwide, offering a diverse array of flavors, textures, and uses. Among the most beloved varieties are cheddar, mozzarella, gouda, brie, and feta, each with its own distinct characteristics and applications. Understanding these cheeses not only enhances your appreciation of their craftsmanship but also empowers you to use them effectively in cooking and pairing.

Cheddar, originating from England, is the most widely consumed cheese globally. Its versatility spans from mild to sharp flavors, depending on aging time—typically 3 to 24 months. Mild cheddar melts smoothly, making it ideal for grilled cheese sandwiches or macaroni and cheese, while sharp cheddar adds a tangy punch to crackers or salads. For optimal flavor, serve aged cheddar at room temperature to release its complex nutty and earthy notes. Pair it with apples, nuts, or a bold red wine like Cabernet Sauvignon for a balanced experience.

Mozzarella, a staple of Italian cuisine, is prized for its soft, stretchy texture and mild, milky taste. Traditionally made from buffalo milk, modern varieties often use cow’s milk for accessibility. Fresh mozzarella, stored in water or whey, is perfect for caprese salads or atop pizzas. Low-moisture mozzarella, firmer and shreddable, is the go-to for baked dishes like lasagna. To elevate its flavor, pair it with fresh basil, tomatoes, and balsamic glaze. Avoid overheating, as it can become rubbery—melt it gently for best results.

Gouda, a Dutch masterpiece, ranges from young and creamy to aged and crystalline. Young gouda has a mild, buttery flavor, excellent for sandwiches or snacking, while aged gouda develops a caramelized, nutty profile, perfect for cheese boards. Its wax rind is edible but often removed for consumption. Gouda pairs beautifully with fruits like pears or quince paste and beverages such as pale ales or chardonnay. For a unique twist, grate aged gouda over roasted vegetables for a savory finish.

Brie, France’s iconic soft cheese, is known for its bloomy rind and rich, creamy interior. Serve it at room temperature to fully appreciate its mushroomy, earthy flavors. Brie is a star on cheese boards, paired with honey, figs, or crusty bread. For cooking, bake it in pastry for a decadent appetizer or melt it into sauces for added depth. Caution: ensure the rind is bloomy and white; avoid if it’s overly dark or ammoniated. Pair brie with sparkling wine or light-bodied reds like Pinot Noir to complement its richness.

Feta, a Greek staple, is a brined cheese with a tangy, salty profile and crumbly texture. Traditionally made from sheep’s or goat’s milk, it’s a key ingredient in salads like Greek salad or spanakopita. Its high acidity and salt content make it a natural preservative, but it can overpower dishes if used excessively—start with small amounts. Feta softens when heated, making it great for stuffing peppers or layering in omelets. For a refreshing pairing, serve it with olives, cucumbers, and a glass of crisp white wine like Assyrtiko.

Each of these dairy cheeses offers a unique sensory experience, rooted in tradition yet adaptable to modern culinary creativity. By understanding their nuances, you can elevate everyday meals and impress guests with thoughtful pairings and preparations. Whether you’re crafting a cheese board or experimenting in the kitchen, cheddar, mozzarella, gouda, brie, and feta are indispensable tools in your culinary arsenal.

Is Cheese Allowed in School? Unpacking Lunchroom Rules and Restrictions

You may want to see also

Cheese-Making Process: Curdling milk, separating whey, pressing curds, and aging

Cheese, a beloved dairy product, begins its journey as milk, undergoing a transformative process that involves curdling, separating whey, pressing curds, and aging. This intricate dance of chemistry and craftsmanship turns a simple liquid into a complex, flavorful solid. The first step, curdling milk, is where the magic starts. By adding a starter culture—bacteria that ferment lactose into lactic acid—the milk’s pH drops, causing proteins to coagulate. For harder cheeses, rennet, an enzyme, is often introduced to speed up this process. The result is a gel-like mass, a delicate balance of science and tradition.

Once curdled, the mixture is cut into smaller pieces, releasing whey—the liquid byproduct rich in lactose and proteins. Separating whey from curds is critical, as it determines the cheese’s texture and moisture content. Soft cheeses retain more whey, while harder varieties require thorough draining. This step demands precision; too much whey left behind can make the cheese crumbly, while excessive removal can lead to dryness. Home cheesemakers often use cheesecloth or specialized molds to gently coax out the whey, a process that can take hours.

Pressing the curds is where cheese begins to take shape—literally. The curds are placed in molds and subjected to pressure, consolidating their structure and expelling remaining whey. The duration and intensity of pressing vary by cheese type; fresh cheeses like ricotta require minimal pressure, while aged cheeses like cheddar need hours or even days under heavy weights. This step is as much art as science, as the right pressure ensures uniformity without sacrificing texture.

Aging, the final stage, is where cheese develops its distinctive flavor, aroma, and texture. During this period, which can range from weeks to years, bacteria and molds continue to work their alchemy. Humidity, temperature, and airflow are meticulously controlled to encourage the growth of desirable microorganisms while preventing spoilage. For example, blue cheese is pierced to allow air in, fostering the growth of Penicillium mold, while hard cheeses like Parmesan are aged in cool, dry environments to develop their crystalline texture. Aging transforms the humble curd into a culinary masterpiece, proving that patience is indeed a virtue in cheesemaking.

Understanding Enzymes' Role in Cheese Making and Flavor Development

You may want to see also

Nutritional Value: High in protein, calcium, fat, and vitamins A and B12

Cheese, a staple in many diets worldwide, is a nutrient-dense food that offers a unique combination of essential macronutrients and micronutrients. Its nutritional profile is particularly notable for its high content of protein, calcium, fat, and vitamins A and B12, making it a valuable addition to a balanced diet. For instance, a single ounce (28 grams) of cheddar cheese provides about 7 grams of protein, 20% of the daily recommended intake of calcium, and significant amounts of vitamins A and B12. This dense nutritional composition makes cheese an efficient way to meet daily nutrient needs, especially for those with higher protein or calcium requirements, such as athletes, growing adolescents, and older adults.

From a practical standpoint, incorporating cheese into meals can be a strategic way to enhance their nutritional value. For example, adding a slice of Swiss cheese to a sandwich not only boosts its protein content but also increases calcium intake, which is crucial for bone health. Similarly, grating Parmesan over a salad or pasta dish can provide a concentrated dose of vitamins A and B12, which play vital roles in immune function, vision, and red blood cell production. However, it’s important to consider portion sizes, as cheese is also calorie-dense. A general guideline is to limit intake to 1-2 ounces per serving to balance nutrient benefits with caloric intake.

Comparatively, cheese stands out among dairy products for its nutrient density. While milk and yogurt are excellent sources of calcium and protein, cheese often contains higher concentrations of these nutrients per gram due to its condensed form. For example, one ounce of cheese can provide as much calcium as a full cup of milk. Additionally, the fermentation process involved in cheese-making enhances its vitamin B12 content, making it a superior source of this nutrient compared to other dairy products. This makes cheese particularly beneficial for individuals following vegetarian or lactose-restricted diets who may struggle to meet their B12 needs.

Persuasively, the nutritional benefits of cheese extend beyond its macronutrient content. Vitamins A and B12, found abundantly in cheese, are essential for overall health but can be difficult to obtain in sufficient quantities from plant-based sources alone. Vitamin A supports skin health and immune function, while B12 is critical for nerve function and DNA synthesis. For those at risk of deficiency, such as vegans, pregnant women, or the elderly, incorporating cheese into the diet can be a practical solution. However, it’s advisable to opt for lower-fat varieties like mozzarella or feta if managing fat intake is a concern, as these still provide the same vitamin benefits with fewer calories.

Finally, while cheese is a nutritional powerhouse, its high fat content warrants mindful consumption. Full-fat cheeses like Brie or blue cheese are rich in saturated fats, which, when consumed in excess, can contribute to cardiovascular risks. To maximize benefits while minimizing risks, consider pairing cheese with fiber-rich foods like whole-grain crackers or fresh vegetables. This not only balances the meal but also slows the absorption of fat, promoting satiety and stable blood sugar levels. For those monitoring fat intake, choosing reduced-fat options or limiting portions to 1-2 ounces per day can help maintain a healthy balance. Cheese, when consumed thoughtfully, can be a delicious and nutritious component of a well-rounded diet.

Mastering the Art of Slicing Wedge Cheese: Tips and Techniques

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Lactose Content: Most aged cheeses have low lactose due to fermentation

Aged cheeses are a lactose-intolerant individual's best friend in the dairy aisle. During the aging process, bacteria feast on lactose, breaking it down into lactic acid. This natural fermentation significantly reduces lactose content, making aged cheeses more digestible for those with sensitivities. For example, a 30g serving of cheddar (aged 6+ months) contains less than 0.01g of lactose, compared to 3g in the same amount of fresh mozzarella.

Hard cheeses like Parmesan, Gruyère, and Pecorino Romano undergo extended aging, often 10 months or more, resulting in lactose levels below 0.1g per serving. This makes them excellent choices for adding savory depth to dishes without triggering discomfort.

Understanding lactose content in cheese is crucial for managing dietary restrictions. While fresh cheeses like ricotta and cottage cheese retain high lactose levels (up to 5g per serving), aged varieties offer a safer alternative. Look for cheeses labeled "aged" or "hard," and check for longer aging times, as these indicate lower lactose. Pairing aged cheeses with lactase enzymes or consuming them in small portions can further minimize symptoms for those with mild intolerance.

The science behind lactose reduction in aged cheeses lies in the activity of lactic acid bacteria. These microorganisms consume lactose as a food source, converting it into lactic acid, which contributes to the cheese's tangy flavor and firm texture. The longer the aging process, the more lactose is metabolized. For instance, a 1-year-old Gouda will have virtually no detectable lactose, making it a safe option even for those with severe intolerance.

Incorporating aged cheeses into a low-lactose diet requires awareness and experimentation. Start with small servings to gauge tolerance, and opt for varieties with the longest aging periods. Combining aged cheeses with naturally lactose-free foods like nuts, fruits, or gluten-free crackers creates satisfying snacks or meals. Remember, while aged cheeses are low in lactose, they are still dairy products, so moderation is key for those with dairy allergies or sensitivities beyond lactose.

Mastering Shredded Cheese Storage: Tips for Freshness and Flavor

You may want to see also

Health Considerations: Benefits and risks for digestion, heart health, and allergies

Dairy cheese, a staple in many diets, offers a complex nutritional profile that can both benefit and challenge health, particularly in digestion, heart health, and allergies. Its rich composition of proteins, fats, and minerals makes it a double-edged sword, depending on individual tolerance and consumption patterns. Understanding these nuances is key to harnessing its potential while mitigating risks.

Digestion: A Balancing Act

Cheese is a concentrated source of protein and fat, which can slow digestion, making it a satisfying food choice. However, its lactose content poses a challenge for those with lactose intolerance. Hard cheeses like cheddar or Parmesan contain minimal lactose, making them more digestible, while softer varieties like mozzarella or brie retain higher levels. For optimal digestion, pair cheese with fiber-rich foods like whole grains or vegetables to counteract its density. Probiotic-rich fermented cheeses, such as Gouda or Swiss, may also support gut health by promoting beneficial bacteria. Limiting portion sizes to 1–2 ounces per serving can prevent discomfort, especially for sensitive individuals.

Heart Health: Weighing the Fats

Cheese is often criticized for its saturated fat content, which has been linked to elevated LDL cholesterol levels. However, recent studies suggest that the relationship between dairy fat and heart health is more complex. Full-fat cheese, when consumed in moderation (e.g., 30–40 grams daily), may not significantly increase cardiovascular risk for most people. Its calcium, vitamin K2, and conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) content can even support arterial health. Opt for lower-fat options like part-skim mozzarella or feta if concerned, but avoid highly processed cheese products, which often contain additives detrimental to heart health. Pairing cheese with unsaturated fats, such as olive oil or nuts, can further balance its impact.

Allergies and Sensitivities: Navigating Reactions

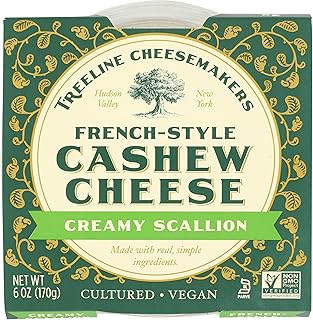

While lactose intolerance is common, true dairy allergies are less frequent but more severe, typically triggered by milk proteins like casein or whey. Symptoms range from mild hives to anaphylaxis, requiring strict avoidance of all dairy products. For those with non-IgE-mediated sensitivities, symptoms like bloating or skin issues may arise hours after consumption. Fermented or aged cheeses, which break down proteins, may be better tolerated in small amounts. Alternatives like almond or cashew cheese can provide similar textures without dairy proteins. Always consult an allergist for testing and personalized advice, especially for children under 5, who are more prone to dairy allergies.

Practical Takeaways for Health-Conscious Consumers

To maximize cheese’s benefits while minimizing risks, adopt a mindful approach. Choose high-quality, minimally processed varieties and monitor portion sizes. Incorporate digestive aids like lactase enzymes if lactose intolerant, and prioritize fermented options for gut health. For heart health, balance cheese intake with a diet rich in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains. If allergies or sensitivities are a concern, explore dairy-free alternatives or consult a healthcare provider for tailored guidance. By understanding cheese’s complexities, you can enjoy its flavor and nutrition without compromising well-being.

Mastering Cheese Storage: Best Practices for Keeping Cheese Blocks Fresh

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, dairy cheese is made from milk, typically from cows, goats, sheep, or buffalo, through a process of curdling and draining.

Yes, dairy cheese is a dairy product because it is derived from milk, which is a primary dairy source.

Many dairy cheeses, especially aged varieties like cheddar or Swiss, contain minimal lactose and may be tolerated by lactose-intolerant individuals, though sensitivity varies.

Yes, dairy cheese contains animal products since it is made from milk, which comes from animals.

No, dairy cheese is made from animal milk, while plant-based cheese is made from ingredients like nuts, soy, or coconut and does not contain dairy.