Gouda cheese, a popular Dutch cheese known for its rich, creamy texture and nutty flavor, undergoes a fermentation process as part of its production. This fermentation is essential to developing its distinctive taste and texture, as it involves the action of lactic acid bacteria that convert lactose into lactic acid. The process not only preserves the cheese but also contributes to its complex flavor profile. Additionally, Gouda can be aged for varying lengths of time, further enhancing its characteristics through continued fermentation and enzymatic activity. Thus, fermentation is a fundamental aspect of Gouda cheese production, making it a key factor in its unique qualities.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Fermentation Process | Yes, Gouda cheese undergoes a fermentation process. |

| Type of Fermentation | Lactic acid fermentation, primarily by lactic acid bacteria. |

| Starter Cultures | Mesophilic or thermophilic bacterial cultures are added to milk. |

| Fermentation Time | Typically 30 minutes to a few hours, depending on the recipe and desired flavor. |

| Role of Fermentation | Converts lactose (milk sugar) into lactic acid, lowering pH, coagulating milk, and developing flavor. |

| Aging Process | After fermentation, Gouda is aged (from a few weeks to several years), during which further fermentation and ripening occur. |

| Flavor Development | Fermentation contributes to Gouda's nutty, sweet, and sometimes caramel-like flavors. |

| Texture | Fermentation and aging affect the texture, making it range from semi-soft to hard. |

| Preservation | Fermentation helps preserve the cheese by creating an environment hostile to harmful bacteria. |

| Probiotic Content | May contain live bacteria, depending on the aging process and pasteurization. |

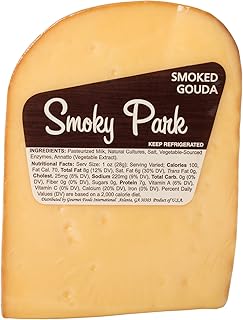

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Fermentation Process: Gouda undergoes lactic acid fermentation, transforming lactose into tangy flavor compounds

- Bacterial Cultures: Specific bacteria strains like Lactococcus lactis initiate Gouda's fermentation

- Aging and Flavor: Longer fermentation deepens Gouda's nutty, caramelized taste profile

- Pasteurization Impact: Raw milk Gouda ferments more naturally than pasteurized versions

- Texture Changes: Fermentation reduces moisture, creating Gouda's firm yet creamy texture

Fermentation Process: Gouda undergoes lactic acid fermentation, transforming lactose into tangy flavor compounds

Gouda cheese, a Dutch staple, owes its distinctive tangy flavor to a precise fermentation process. At the heart of this transformation is lactic acid fermentation, a metabolic pathway where lactose—the natural sugar in milk—is broken down by lactic acid bacteria. These bacteria, naturally present in raw milk or added as starter cultures, convert lactose into lactic acid, lowering the cheese’s pH and creating the characteristic sharpness Gouda is known for. This process not only develops flavor but also preserves the cheese by inhibiting harmful bacteria.

The fermentation of Gouda is a delicate balance of time, temperature, and microbial activity. After curdling the milk with rennet, the curds are cut, heated, and pressed into molds. During aging, which can range from a few weeks to several years, lactic acid bacteria continue to metabolize residual lactose, producing compounds like diacetyl and acetaldehyde that contribute to Gouda’s nutty, caramelized notes. Younger Goudas retain more lactose, resulting in a milder, sweeter profile, while aged varieties become firmer and tangier as fermentation progresses.

For home cheesemakers, replicating Gouda’s fermentation requires attention to detail. Start by using a mesophilic starter culture, which thrives at temperatures between 20–30°C (68–86°F), ideal for Gouda’s fermentation. Maintain a consistent aging environment—a cool, humid space around 13°C (55°F) with 85% humidity—to encourage slow, controlled fermentation. Regularly flip and brine the cheese to develop its rind and prevent mold growth. Patience is key; even young Gouda benefits from at least 4 weeks of aging to allow fermentation to deepen its flavor.

Comparatively, Gouda’s fermentation process differs from cheeses like Cheddar, which undergoes cheddaring and mechanical acid development, or blue cheeses, which rely on mold cultures. Gouda’s reliance on lactic acid bacteria alone highlights its simplicity and purity of flavor. This method also makes it a suitable option for those with mild lactose intolerance, as the fermentation significantly reduces lactose content. A 30g serving of aged Gouda, for instance, contains less than 1g of lactose, making it a tangy, fermented treat that’s both accessible and indulgent.

In essence, Gouda’s fermentation is a masterclass in how microbial activity can elevate a simple ingredient. By harnessing lactic acid bacteria, cheesemakers transform milk into a complex, tangy delight. Whether you’re crafting Gouda at home or savoring a slice, understanding this process deepens appreciation for the science and artistry behind every bite.

Crunchy Delight: Carb Count in Batter-Fried Cheese Curds Revealed

You may want to see also

Bacterial Cultures: Specific bacteria strains like Lactococcus lactis initiate Gouda's fermentation

Gouda cheese, a Dutch staple renowned for its rich flavor and smooth texture, owes its distinctive character to a carefully orchestrated fermentation process. At the heart of this transformation are specific bacterial cultures, with *Lactococcus lactis* taking center stage. This lactic acid bacterium is the primary starter culture responsible for initiating the fermentation that defines Gouda’s development. By converting lactose (milk sugar) into lactic acid, *Lactococcus lactis* lowers the pH of the milk, creating an environment that encourages coagulation and inhibits unwanted microbial growth. This initial step is critical, as it sets the foundation for the cheese’s texture, flavor, and safety.

The role of *Lactococcus lactis* extends beyond mere acidification. During fermentation, it produces enzymes and metabolites that contribute to Gouda’s complex flavor profile. For instance, diacetyl, a byproduct of its metabolism, imparts buttery and nutty notes, while other compounds add depth and richness. The strain’s activity also influences the cheese’s moisture content and structure, ensuring the characteristic firmness yet creaminess that Gouda is celebrated for. Interestingly, the specific subspecies and strains of *Lactococcus lactis* used can vary, allowing cheesemakers to fine-tune the final product’s attributes.

In practice, introducing *Lactococcus lactis* into milk requires precision. Typically, a dosage of 0.5–1.0% of starter culture (by weight of milk) is added, though this can vary based on the desired fermentation rate and flavor intensity. The milk is then maintained at an optimal temperature of 30–32°C (86–90°F) to encourage bacterial activity. Over 12–24 hours, the pH drops to around 5.0–5.4, signaling the completion of the initial fermentation phase. This step is crucial, as insufficient fermentation can lead to a bland or unstable cheese, while over-fermentation may result in excessive acidity or texture defects.

While *Lactococcus lactis* is the star, it often works in tandem with secondary bacteria and molds, particularly during aging. For example, *Propionibacterium freudenreichii* may be introduced to create the distinctive eye formation in some Gouda varieties, while surface molds like *Penicillium camemberti* can add complexity during ripening. However, the primary fermentation driven by *Lactococcus lactis* remains the cornerstone of Gouda’s identity. For home cheesemakers, selecting a high-quality starter culture and monitoring temperature and pH are essential to replicating this process successfully.

In conclusion, the fermentation of Gouda cheese is a testament to the precision and artistry of bacterial cultures, with *Lactococcus lactis* playing an indispensable role. Its ability to transform milk into a flavorful, textured cheese highlights the interplay between science and tradition. Whether crafting Gouda in a commercial facility or a home kitchen, understanding and respecting the role of these bacteria ensures a product that honors the cheese’s storied legacy.

Why Cheese Costs More: Uncovering the Pricey Dairy Dilemma

You may want to see also

Aging and Flavor: Longer fermentation deepens Gouda's nutty, caramelized taste profile

Gouda cheese, a Dutch masterpiece, undergoes a transformative journey during fermentation, but it's the aging process that truly unlocks its complex flavor profile. As Gouda matures, its texture evolves from supple and creamy to firm and crystalline, while its taste intensifies, revealing layers of nuttiness and caramelized sweetness. This phenomenon is a direct result of extended fermentation, which allows enzymes and bacteria to work their magic, breaking down proteins and fats into smaller, more flavorful compounds.

Consider the aging process as a delicate dance between time and temperature. Young Goudas, aged for 1-6 months, exhibit mild, buttery flavors with subtle hints of sweetness. As the cheese matures, typically between 6-12 months, its flavor profile deepens, showcasing more pronounced nutty and fruity notes. For the ultimate indulgence, seek out Goudas aged 12-24 months or longer, where the fermentation process reaches its zenith, yielding a rich, caramelized taste with a satisfying crunch from tyrosine crystals. To appreciate the nuances, try a vertical tasting: sample Goudas of varying ages side by side, noting the subtle differences in texture and flavor.

The science behind this flavor development lies in the breakdown of proteins and fats during extended fermentation. As Gouda ages, protein-degrading enzymes (proteases) cleave complex proteins into simpler amino acids, some of which contribute to the cheese's nutty and brothy flavors. Simultaneously, fat-degrading enzymes (lipases) release fatty acids, adding complexity and depth to the taste profile. For instance, the presence of butyric acid, a short-chain fatty acid, can impart a subtle, sweet, and creamy note, while other fatty acids contribute to the overall richness and mouthfeel.

To maximize the flavor potential of aged Goudas, consider the following practical tips: pair older, more complex Goudas with bold, full-bodied wines like Cabernet Sauvignon or Syrah to complement their rich, caramelized flavors. For younger Goudas, opt for lighter, fruitier wines such as Pinot Noir or Riesling. When serving, allow the cheese to come to room temperature, as this will enhance its aroma and texture. Finally, experiment with different age categories to discover your preferred flavor profile – whether it's the mild, buttery notes of young Gouda or the intense, crystalline crunch of an aged masterpiece. By understanding the role of fermentation and aging in Gouda's flavor development, you'll be better equipped to select, serve, and savor this exquisite cheese.

Is Chucky Cheese Scary? Unraveling the Nostalgia and Fear Factor

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Pasteurization Impact: Raw milk Gouda ferments more naturally than pasteurized versions

Raw milk Gouda undergoes a fermentation process that is inherently more dynamic and complex than its pasteurized counterpart. This is because raw milk contains a diverse array of native bacteria and enzymes that contribute to the cheese’s flavor, texture, and aroma. During fermentation, these microorganisms break down lactose into lactic acid, creating an environment where beneficial bacteria thrive and undesirable pathogens are inhibited. In pasteurized Gouda, the milk is heated to destroy bacteria, both good and bad, which limits the natural fermentation process. As a result, raw milk Gouda often develops deeper, more nuanced flavors over time, while pasteurized versions may rely on added cultures to achieve fermentation, yielding a more standardized but less intricate profile.

To understand the practical implications, consider the aging process. Raw milk Gouda can be aged for 12 months or more, during which its flavors intensify and its texture becomes firmer and more crystalline. This extended aging is possible because the natural bacteria continue to work, breaking down proteins and fats in ways that pasteurized cheese cannot replicate. For instance, a raw milk Gouda aged for 18 months might exhibit notes of butterscotch, hazelnut, and caramel, whereas a pasteurized version of the same age may lack these complex layers. Home cheesemakers or enthusiasts should note that raw milk Gouda requires careful temperature control (ideally 50–55°F) and humidity (85–90%) to support this slow, natural fermentation.

From a health perspective, the debate between raw and pasteurized Gouda often centers on safety versus nutritional benefits. Pasteurization eliminates pathogens like *Listeria* and *Salmonella*, making it a safer option for vulnerable populations, such as pregnant women or the immunocompromised. However, raw milk Gouda retains beneficial probiotics, such as *Lactobacillus* and *Bifidobacterium*, which support gut health. For those prioritizing flavor and microbial diversity, raw milk Gouda is the clear choice, but it must be sourced from reputable producers who adhere to strict hygiene standards to minimize risk.

Finally, the choice between raw and pasteurized Gouda ultimately depends on your priorities. If you seek a cheese with a rich, evolving flavor profile and are willing to invest in proper storage and sourcing, raw milk Gouda is unparalleled. Conversely, pasteurized Gouda offers consistency and safety, making it a reliable option for everyday use. For optimal results, pair raw milk Gouda with bold accompaniments like dark honey or robust red wines to highlight its complexity, while pasteurized versions pair well with milder flavors like apples or light crackers. Understanding the pasteurization impact allows you to make an informed decision that aligns with your taste preferences and lifestyle.

Training Your Cheese Plant: Vertical Growth Tips and Techniques

You may want to see also

Texture Changes: Fermentation reduces moisture, creating Gouda's firm yet creamy texture

Fermentation is the silent sculptor of Gouda’s signature texture, transforming a pliable curd into a cheese that balances firmness with creaminess. During this process, lactic acid bacteria metabolize lactose, lowering the pH and expelling moisture as a byproduct. Young Goudas retain more water, resulting in a softer, almost rubbery mouthfeel, while aged varieties become denser as moisture evaporates over time. This gradual dehydration is not a flaw but a feature, as it concentrates fats and proteins, creating a texture that yields under pressure yet retains structural integrity. Think of it as the cheese equivalent of a well-aged leather—supple yet sturdy.

To understand this transformation, consider the fermentation timeline. A 4-week Gouda loses approximately 10-15% of its initial moisture content, while a 12-month aged wheel can shed up to 30%. This moisture loss is deliberate, guided by controlled humidity and temperature in aging rooms. For home cheesemakers, replicating this requires precision: maintain a relative humidity of 85-90% for young Goudas and reduce it to 75-80% for aged versions. Too much moisture retention results in a gummy texture; too little, and the cheese becomes crumbly. The goal is a Goldilocks zone where firmness meets melt-in-your-mouth creaminess.

The science behind this texture shift lies in the protein matrix. As moisture decreases, casein proteins tighten, forming a denser network. Simultaneously, fermentation-produced enzymes break down fats into smaller molecules, contributing to the creamy sensation. This dual process is why a slice of aged Gouda can simultaneously snap when bent yet coat your palate with richness. For optimal results, pair younger Goudas (3-6 months) with crisp apples to contrast their semi-firm bite, and reserve older varieties (12+ months) for grating over dishes where their crystalline texture can shine.

Practical tip: If your homemade Gouda feels too moist, extend the pressing time during production by 2-4 hours, and ensure proper salting to draw out excess water. Conversely, if it’s overly dry, reduce aging room ventilation slightly to slow moisture loss. The texture of Gouda is not static but a dynamic interplay of fermentation and environment—a reminder that cheese is as much a living craft as a culinary product. Master this balance, and you’ll unlock the full potential of Gouda’s textural duality.

Is Fudge Cheese a Myth or a Delicious Reality?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, Gouda cheese is fermented as part of its production process.

Fermentation in Gouda cheese is driven by lactic acid bacteria, which convert lactose (milk sugar) into lactic acid, lowering the pH and aiding in curd formation and flavor development.

The fermentation time for Gouda cheese varies depending on the type, but it typically ranges from a few hours to several days during the initial stages of production.

Yes, fermentation significantly influences the flavor of Gouda cheese, contributing to its characteristic nutty, sweet, and sometimes tangy taste, depending on the aging process.