Halloumi, a popular cheese known for its unique texture and ability to hold its shape when grilled or fried, often sparks curiosity about its origins and ingredients. One common question is whether halloumi is made from sheep's milk. Traditionally, halloumi is produced from a mixture of sheep's and goat's milk, though cow's milk is increasingly used in modern variations, especially in commercial production. This blend of milks contributes to its distinctive flavor and firm yet slightly springy consistency. While sheep's milk is a key component in authentic halloumi, the exact composition can vary depending on regional practices and availability of milk sources. Understanding its origins helps appreciate the rich cultural and culinary heritage of this beloved cheese.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Origin | Cyprus |

| Primary Milk Source | Sheep and/or Goat |

| Cow's Milk Usage | Often mixed with sheep/goat milk |

| Texture | Semi-hard, squeaky when grilled |

| Flavor | Mild, slightly salty |

| Melting Point | High, does not melt completely |

| Traditional Use | Grilled or fried |

| Shelf Life | Relatively long, especially in brine |

| Common Allergens | Milk (lactose may be reduced in aged versions) |

| Vegetarian-Friendly | Yes, uses microbial rennet |

| Sheep's Cheese Exclusivity | Not exclusively; often a blend |

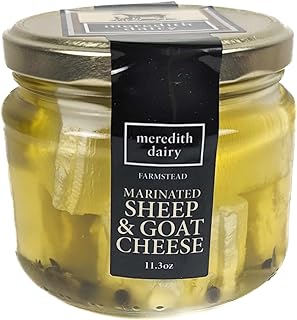

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Halloumi's Origin: Traditionally made from sheep's and goat's milk, halloumi originated in Cyprus

- Modern Variations: Some halloumi uses cow's milk, reducing reliance on sheep's milk

- Sheep's Milk Benefits: Higher fat content in sheep's milk enhances halloumi's texture and flavor

- Authenticity Debate: Purists argue halloumi must use sheep's milk to be considered authentic

- Labeling Standards: Regulations require clear labeling if halloumi contains sheep's milk or alternatives

Halloumi's Origin: Traditionally made from sheep's and goat's milk, halloumi originated in Cyprus

Halloumi's roots are deeply embedded in the agricultural traditions of Cyprus, where shepherds historically relied on sheep and goats for milk due to their adaptability to the island's rugged terrain. Unlike cows, which require more fertile land and resources, sheep and goats thrive in Cyprus’s rocky, arid environment, making their milk the practical choice for early cheese production. This necessity-driven decision laid the foundation for halloumi’s distinctive character, as the higher fat and protein content in sheep and goat milk contributes to its signature firmness and melt-resistant texture.

To recreate traditional halloumi at home, start by sourcing high-quality sheep’s and goat’s milk, ideally unpasteurized for authenticity, though pasteurized milk can be used with slight adjustments. Heat 1 gallon (3.8 liters) of milk to 86°F (30°C), then add 1/4 teaspoon of liquid rennet diluted in 1/4 cup of water and stir gently for 1 minute. Allow the mixture to set for 45 minutes until a firm curd forms. Cut the curd into 1-inch cubes, reheat to 104°F (40°C), and stir for 10 minutes to release whey. Drain, press the curds into a mold, and brine in a solution of 1 quart (1 liter) water, 1/2 cup salt, and optional herbs for 24 hours. This process preserves the cheese’s elasticity and savory tang, hallmarks of its Cypriot heritage.

While halloumi is traditionally made from sheep’s and goat’s milk, modern variations often incorporate cow’s milk to reduce costs and increase yield. However, purists argue that this substitution dilutes the cheese’s cultural identity and alters its texture. Cypriot halloumi, protected by the EU’s Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) status, must contain a minimum of 51% sheep’s and goat’s milk, ensuring its authenticity. When selecting halloumi, look for PDO certification to guarantee adherence to traditional methods and ingredients.

The enduring appeal of halloumi lies in its versatility and connection to its origins. Its ability to withstand high heat without melting, a result of its sheep and goat milk composition, makes it ideal for grilling, frying, or serving fresh. Pair it with watermelon and mint for a classic Cypriot meze, or use it as a protein-rich addition to salads. By understanding and respecting its traditional production methods, consumers can fully appreciate halloumi’s unique place in culinary history and its role as a testament to Cyprus’s pastoral heritage.

Creative Ways to Use Up Leftover Cheese in Delicious Recipes

You may want to see also

Modern Variations: Some halloumi uses cow's milk, reducing reliance on sheep's milk

Halloumi's traditional recipe calls for a mixture of sheep's and goat's milk, a combination that lends the cheese its distinctive flavor and texture. However, modern variations are increasingly incorporating cow's milk, either as a partial or complete substitute. This shift is driven by practicality: cow's milk is more readily available and often less expensive than sheep's milk, making it an attractive option for large-scale production. For home cheesemakers or small-batch producers, this means experimenting with ratios—typically starting with 70% cow's milk and 30% sheep's milk—to balance cost and authenticity.

From a nutritional standpoint, the switch to cow's milk alters halloumi's profile subtly. Sheep's milk is higher in fat and protein, contributing to the cheese's rich, creamy mouthfeel. Cow's milk, while lower in fat, can still produce a satisfactory texture when combined with proper technique, such as brining and heating. For those with dietary restrictions, cow's milk halloumi may be easier to digest, though it lacks the nuanced flavor of its traditional counterpart. A practical tip: if using cow's milk, add a pinch of citric acid during curdling to enhance acidity and improve texture.

The economic implications of this modern variation cannot be overlooked. In regions where sheep farming is less prevalent, cow's milk halloumi allows local producers to enter the market without relying on imported ingredients. This democratization of production has led to innovative twists, such as smoked or herb-infused halloumi, which cater to diverse palates. For consumers, this means more options at varying price points, though purists may argue that the essence of halloumi is lost in translation.

Finally, the sensory experience of cow's milk halloumi differs slightly but is not inherently inferior. When grilled, it achieves the signature squeak and golden crust, though the flavor may lean milder and less complex. To elevate it, pair with bold accompaniments like harissa or fig jam. For a closer approximation of traditional halloumi, blend cow's milk with a small amount of sheep's milk or goat's milk, if available. This hybrid approach bridges tradition and innovation, offering a halloumi that is both accessible and satisfying.

Mastering Malcore's Wisconsin Cheese Curds: A Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

Sheep's Milk Benefits: Higher fat content in sheep's milk enhances halloumi's texture and flavor

Halloumi, a cheese celebrated for its unique ability to hold its shape when grilled or fried, owes much of its character to the milk from which it is made. While traditionally crafted from sheep's milk, modern variations often incorporate goat's or cow's milk. However, it is the higher fat content in sheep's milk that significantly enhances halloumi's texture and flavor, making it the preferred choice for purists and connoisseurs alike.

Analytical Insight: Sheep's milk contains approximately 6-8% fat, compared to 3.5-4% in cow's milk and 4-5% in goat's milk. This elevated fat content contributes to halloumi's rich, creamy mouthfeel and its ability to brown beautifully when cooked. The fat globules in sheep's milk are also smaller, allowing for better distribution throughout the cheese, resulting in a smoother, more consistent texture. For those seeking to replicate the authentic halloumi experience, using sheep's milk is not just a tradition but a scientific advantage.

Instructive Guidance: If you’re making halloumi at home, opt for sheep's milk to achieve the desired texture and flavor. Start by heating 1 gallon of sheep's milk to 86°F (30°C), then add 1/4 teaspoon of mesophilic culture and let it ripen for 45 minutes. Next, stir in 1/4 teaspoon of liquid rennet diluted in 1/4 cup of cool water. Allow the mixture to set for 45 minutes until a firm curd forms. Cut the curd into 1-inch cubes, gently stir for 10 minutes, and gradually increase the temperature to 95°F (35°C). The higher fat content in sheep's milk will ensure the curds meld together seamlessly, creating a cohesive cheese that slices and grills perfectly.

Persuasive Argument: Beyond texture, the fat in sheep's milk imparts a distinct nutty, slightly sweet flavor to halloumi that cow's or goat's milk cannot replicate. This flavor profile is particularly pronounced when the cheese is heated, as the fat caramelizes, adding depth and complexity. For chefs and home cooks alike, using sheep's milk halloumi elevates dishes—whether it’s a grilled cheese sandwich, a salad topping, or a standalone appetizer. The investment in quality ingredients pays off in the final taste experience.

Comparative Perspective: While cow's milk halloumi is more common due to its lower cost and wider availability, it lacks the richness and structural integrity of its sheep's milk counterpart. Goat's milk halloumi, though closer in fat content to sheep's milk, has a tangier flavor that can overpower the subtle nuances halloumi is known for. Sheep's milk strikes the perfect balance, offering both the fat needed for texture and the flavor profile that defines authentic halloumi. For those who value tradition and quality, sheep's milk is the undisputed choice.

Descriptive Takeaway: Imagine biting into a piece of halloumi—its exterior golden and crisp, its interior soft and yielding. The higher fat content in sheep's milk ensures that each bite is luxuriously creamy, with a flavor that lingers on the palate. Whether enjoyed hot off the grill or cold in a salad, sheep's milk halloumi delivers a sensory experience that is both comforting and sophisticated. For anyone curious about the origins of halloumi's appeal, the answer lies in the milk that makes it—sheep's milk, with its unparalleled fat content, is the secret to its success.

Is Brie Cheese Truly French? Exploring Its Origins and Authenticity

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Authenticity Debate: Purists argue halloumi must use sheep's milk to be considered authentic

Halloumi's identity crisis begins with its milk. Traditionally, this Cypriot cheese was crafted from sheep's milk, a fact rooted in the island's pastoral heritage. Yet, modern production often substitutes cow's milk, sparking a fiery debate among purists. They argue that deviating from sheep's milk strips halloumi of its authentic character, reducing it to a mere imitation of the original. This isn’t just about taste—it’s about preserving cultural integrity.

Consider the process. Sheep's milk is richer in fat and protein, contributing to halloumi's signature texture: firm yet springy, ideal for grilling. Cow's milk, while more accessible and cost-effective, yields a milder flavor and slightly softer consistency. For purists, this difference is non-negotiable. They insist that using sheep's milk isn’t a preference but a requirement for authenticity. After all, the Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) status for halloumi in the EU mandates a minimum of 51% sheep's and/or goat's milk, underscoring its historical roots.

However, practicality often trumps tradition. Sheep's milk is scarce and expensive, making large-scale production with cow's milk a necessity for global demand. This raises a question: Can halloumi evolve while retaining its essence? Purists say no, but pragmatists argue that adaptation is survival. Still, the debate persists, leaving consumers to decide whether authenticity lies in strict adherence to tradition or in the spirit of the cheese itself.

For those seeking the "real" halloumi experience, look for labels indicating sheep's milk content. Artisanal producers often prioritize traditional methods, offering a product closer to the original. Pair it with fresh figs or grill it until golden for a taste that purists revere. Ultimately, the authenticity debate isn’t just about milk—it’s about honoring heritage in a changing world.

Should You Refrigerate Cheese Danish? Storage Tips for Freshness

You may want to see also

Labeling Standards: Regulations require clear labeling if halloumi contains sheep's milk or alternatives

Halloumi's traditional recipe calls for a mixture of sheep's and goat's milk, but modern variations often include cow's milk to meet demand and reduce costs. This shift raises questions about labeling transparency, as consumers may assume they're buying the classic version. Regulations mandate clear labeling to distinguish between traditional halloumi and alternatives, ensuring buyers know exactly what they're getting. For instance, the European Union's Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) status for Cypriot halloumi requires a minimum of 51% sheep's and/or goat's milk, with cow's milk allowed only as a supplement. Labels must reflect this composition, often stating "contains sheep's milk" or "made with cow's milk."

When shopping for halloumi, look for terms like "traditional," "authentic," or "PDO" to ensure you're getting the sheep's milk-based version. However, these labels aren't always present, especially in non-European markets. In such cases, scrutinize the ingredient list for milk sources. Phrases like "sheep's milk (50%), cow's milk (50%)" provide clarity, while vague terms like "milk" or "dairy" should prompt further inquiry. For those with dietary restrictions or preferences, this distinction is crucial. Sheep's milk halloumi tends to be richer and tangier, while cow's milk versions are milder and creamier. Knowing the difference allows you to choose based on taste, texture, and nutritional needs.

Regulations vary by region, complicating matters for international consumers. In the United States, for example, halloumi isn't subject to the same PDO restrictions as in the EU, allowing for more flexibility in milk composition. However, the FDA still requires accurate labeling of milk types under the Food Allergen Labeling and Consumer Protection Act (FALCPA). This means U.S. labels should clearly state "sheep's milk," "goat's milk," or "cow's milk" to avoid confusion. If you're unsure, contact the manufacturer directly for clarification. Apps like MyFitnessPal or barcode scanners can also provide ingredient breakdowns, though these aren’t always up-to-date.

For home cooks and chefs, understanding halloumi's milk composition impacts recipe outcomes. Sheep's milk halloumi has a higher melting point and firmer texture, making it ideal for grilling or frying without falling apart. Cow's milk versions may soften more quickly, better suited for salads or sandwiches. When substituting, consider the milk type to maintain dish integrity. For instance, using cow's milk halloumi in a traditional Cypriot recipe might alter the expected flavor profile. Always check labels to ensure the product aligns with your culinary goals.

In summary, labeling standards are your best tool for navigating halloumi's milk variations. Whether you're seeking authenticity, accommodating dietary needs, or perfecting a recipe, clear labels provide the information you need. Stay informed about regional regulations, read ingredient lists carefully, and don’t hesitate to seek additional details when labels are unclear. By doing so, you’ll make confident choices that align with your preferences and requirements.

Effortlessly Open Your Pampered Chef Cheese Grater: A Quick Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, halloumi is traditionally made from a mixture of sheep's and goat's milk, but modern versions may also include cow's milk.

Halloumi is often associated with sheep's milk due to its traditional recipe, but it is not exclusively a sheep's cheese, as it can contain other types of milk.

Halloumi made primarily with sheep's milk tends to have a richer, slightly tangier flavor compared to versions made with cow's milk.

If halloumi is made solely from sheep's milk, it may be suitable for those with cow's milk allergies, but always check the label to ensure no cow's milk is included.

Sheep's milk is traditionally used in halloumi because it was widely available in the regions where the cheese originated, such as Cyprus, and it contributes to the cheese's distinctive texture and flavor.