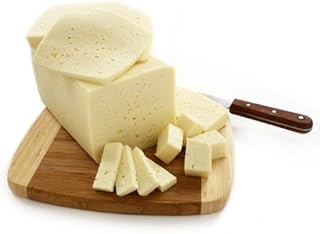

Havarti cheese, often mistaken for an Italian variety due to its mild, buttery flavor and creamy texture, actually originates from Denmark. Created in the mid-19th century by Danish cheese maker Hanne Nielsen, Havarti is a semi-soft cow's milk cheese known for its small, irregular holes and versatility in cooking. While Italy is renowned for its own rich cheese traditions, such as mozzarella and Parmigiano-Reggiano, Havarti’s roots are firmly Scandinavian, making it a distinct product of Danish dairy craftsmanship rather than Italian cuisine.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Origin | Denmark |

| Type | Semi-soft cheese |

| Milk Source | Cow's milk |

| Texture | Creamy, smooth, and slightly crumbly |

| Flavor | Mild, buttery, and slightly tangy |

| Appearance | Pale yellow interior with small, irregular holes |

| Aging Time | 3 to 12 months |

| Italian Origin | No |

| Cultural Association | Danish cuisine, not Italian |

| Common Uses | Sandwiches, grilled cheese, cheese boards, melting |

| Italian Cheese Counterpart | None (Havarti is not an Italian cheese) |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Havarti Origin: Havarti cheese originated in Denmark, not Italy, despite its Italian-sounding name

- Italian Cheeses: Italy has its own cheeses like Parmigiano-Reggiano, not including Havarti

- Havarti Characteristics: Semi-soft, Danish cheese with mild flavor, unlike Italian varieties

- Name Confusion: Havarti’s name may mislead, but it’s distinctly Danish, not Italian

- Italian Cheese Culture: Italy’s cheese tradition focuses on regional specialties, excluding Havarti

Havarti Origin: Havarti cheese originated in Denmark, not Italy, despite its Italian-sounding name

Havarti cheese, with its creamy texture and mild, buttery flavor, often finds itself mistakenly categorized as an Italian creation. However, a closer look at its history reveals a Danish origin story that dates back to the mid-19th century. Created by Hanne Nielsen, a Danish farmer’s wife, Havarti was initially known as *Danish Port Salut* due to its similarity to the French cheese. The name "Havarti" was later adopted, inspired by Havartigaard, the farm where Nielsen perfected her recipe. This Danish heritage is a testament to the country’s rich dairy tradition, not Italy’s.

To appreciate Havarti’s Danish roots, consider its production process, which aligns with Scandinavian dairy practices. Made from cow’s milk, the cheese is semi-soft and features small, irregular holes, a result of the specific bacterial cultures used during fermentation. Unlike Italian cheeses like mozzarella or Parmigiano-Reggiano, Havarti is not aged for long periods; it’s typically ready for consumption after 3 to 5 months. This shorter aging process contributes to its mild flavor, making it a versatile ingredient in both Danish and international cuisines.

One practical tip for enjoying Havarti is to pair it with traditional Danish foods to honor its origin. Try it melted on a Danish open-faced sandwich (*smørrebrød*) or alongside rye bread and pickled herring. For a modern twist, incorporate it into pasta dishes or grilled cheese sandwiches, showcasing its adaptability. However, always remember: while its Italian-sounding name might suggest otherwise, Havarti’s soul is undeniably Danish.

A comparative analysis highlights the contrast between Havarti and Italian cheeses. While Italian varieties often emphasize bold flavors and specific regional techniques (e.g., buffalo milk for mozzarella), Havarti’s appeal lies in its simplicity and accessibility. Its Danish origin also explains its prominence in Scandinavian cheese boards, often paired with fruits, nuts, and crispbreads. This distinction is crucial for cheese enthusiasts seeking to understand the cultural and culinary contexts of their favorites.

In conclusion, Havarti’s Italian-sounding name is a mere coincidence, not a reflection of its heritage. By recognizing its Danish origin, you not only deepen your cheese knowledge but also pay homage to the craftsmanship of Hanne Nielsen. Next time you enjoy a slice of Havarti, savor it as a piece of Danish history, not an Italian impostor.

Master Cold Smoking Cheese in Your Pellet Smoker: Easy Steps

You may want to see also

Italian Cheeses: Italy has its own cheeses like Parmigiano-Reggiano, not including Havarti

Havarti, with its creamy texture and mild flavor, is often mistaken for an Italian cheese due to its popularity in Mediterranean-style dishes. However, a quick search reveals that Havarti is Danish in origin, named after a farm in Denmark. This highlights a common misconception: not all cheeses used in Italian cuisine are Italian. Italy, however, boasts a rich tradition of cheesemaking, with over 400 varieties, each tied to specific regions and techniques. Among these, Parmigiano-Reggiano stands out as a quintessential Italian cheese, protected by a DOP designation that ensures its authenticity and quality.

To truly appreciate Italian cheeses, it’s essential to understand their regional roots. Parmigiano-Reggiano, for instance, is produced exclusively in Emilia-Romagna, using centuries-old methods. Its complex, nutty flavor develops over a minimum of 12 months of aging, with some wheels maturing for up to 36 months. This contrasts sharply with Havarti, which is typically aged for just 3 to 5 months. While Havarti’s versatility makes it a favorite in sandwiches and melts, Parmigiano-Reggiano’s granular texture and robust flavor make it ideal for grating over pasta or enjoying in shards with balsamic glaze.

When exploring Italian cheeses, it’s instructive to compare them to non-Italian varieties like Havarti. For example, while Havarti’s mildness pairs well with light wines, Parmigiano-Reggiano’s depth complements full-bodied reds like Barolo. Another standout Italian cheese is Pecorino Romano, a sheep’s milk cheese with a sharp, salty profile, often used in pasta dishes like cacio e pepe. Unlike Havarti, Pecorino Romano’s intensity demands specific pairings, such as hearty breads or robust sauces. These contrasts underscore Italy’s commitment to crafting cheeses with distinct identities.

For those looking to incorporate Italian cheeses into their culinary repertoire, start with a classic: a cheese board featuring Parmigiano-Reggiano, Gorgonzola (a creamy blue cheese), and fresh mozzarella. Pair these with Italian staples like prosciutto, olives, and crusty bread. Avoid the temptation to include Havarti, as it dilutes the authenticity of the experience. Instead, use this opportunity to educate your palate about the nuances of Italian cheesemaking. Remember, while Havarti has its place, Italy’s cheeses offer a depth of history and flavor that deserve their own spotlight.

Finally, a practical tip: when purchasing Italian cheeses, look for DOP or PDO labels, which guarantee the product’s origin and traditional production methods. For instance, authentic Parmigiano-Reggiano will have a dotted imprint of “Parmigiano-Reggiano” around the rind. This ensures you’re getting the real deal, not an imitation. By focusing on Italy’s unique cheeses, you not only elevate your dishes but also honor the craftsmanship behind them—something Havarti, despite its charm, cannot claim.

Is Chucky Cheese Closed? Exploring the Status of a Childhood Favorite

You may want to see also

Havarti Characteristics: Semi-soft, Danish cheese with mild flavor, unlike Italian varieties

Havarti cheese, with its semi-soft texture and mild, buttery flavor, is a Danish creation that often gets mistaken for Italian varieties. Unlike the bold, pungent profiles of Italian cheeses like Parmigiano-Reggiano or Gorgonzola, Havarti’s subtlety makes it a versatile ingredient in both cooking and pairing. Its Danish origins trace back to the mid-19th century, when Hanne Nielsen, a Danish farmer’s wife, experimented with washed-curd techniques, resulting in a cheese that melts beautifully without overpowering other flavors. This historical context underscores Havarti’s unique identity, firmly rooted in Danish tradition rather than Italian cheesemaking.

To appreciate Havarti’s distinct characteristics, consider its texture and flavor profile. Semi-soft and slightly springy, it offers a creamy mouthfeel without the crumbly dryness of harder Italian cheeses. Its mild, nutty taste pairs well with fruits, crackers, or sandwiches, making it a go-to for those who prefer subtlety over intensity. For practical use, Havarti’s melting properties are ideal for grilled cheese sandwiches or sauces, where it adds richness without dominating the dish. In contrast, Italian cheeses like mozzarella or provolone, while also meltable, bring a sharper tang or stretchiness that Havarti lacks.

When comparing Havarti to Italian cheeses, the differences become even more pronounced. Italian varieties often rely on aging to develop complex flavors—think of the crystalline sharpness of aged Parmesan or the earthy depth of Pecorino. Havarti, however, is typically aged for just 3 to 6 months, preserving its mildness and softness. This shorter aging process aligns with its Danish heritage, where cheeses are often designed to complement rather than compete with other ingredients. For instance, pairing Havarti with a light white wine or a crisp apple highlights its gentle nature, whereas Italian cheeses might demand bolder accompaniments like red wine or cured meats.

To incorporate Havarti into your culinary repertoire, start with simple applications. Use thin slices in a panini for a creamy, melt-in-your-mouth experience, or cube it for a cheese board alongside honey and nuts. For a more adventurous approach, grate Havarti over roasted vegetables or pasta dishes to add a subtle richness without overwhelming the dish. Avoid using it in recipes where a strong cheese flavor is essential, as its mildness may get lost. By understanding Havarti’s Danish roots and unique qualities, you’ll appreciate why it stands apart from Italian cheeses and how to best utilize its charm.

Exploring the Origins of Chicken and Cheese Empanadas

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Name Confusion: Havarti’s name may mislead, but it’s distinctly Danish, not Italian

Havarti cheese, with its creamy texture and mild, buttery flavor, often finds itself mistakenly grouped with Italian cheeses like mozzarella or provolone. This confusion likely stems from its name, which lacks the obvious Danish markers found in cheeses like Danablu or Esrom. Unlike Italian cheeses, which often carry regional names (think Parmigiano-Reggiano or Gorgonzola), Havarti’s moniker doesn’t immediately reveal its Danish origins. This linguistic ambiguity, combined with its versatility in dishes typically associated with Italian cuisine (pizza, panini), perpetuates the misconception.

To clarify, Havarti is a semi-soft cow’s milk cheese developed in the mid-19th century by Danish cheese pioneer Hanne Nielsen. Its creation was part of Denmark’s broader effort to modernize dairy production, a movement that also gave rise to other Danish cheeses. The name “Havarti” itself is derived from Havarthigaard, the farm where Nielsen experimented with cheese-making techniques. This historical context underscores its Danish heritage, a fact often overshadowed by its Italian-sounding name and global popularity.

From a culinary perspective, Havarti’s characteristics further distinguish it from Italian cheeses. While Italian varieties like Pecorino Romano or Asiago are often aged for hardness and sharpness, Havarti is typically aged for just 3–6 months, resulting in a smoother, more delicate profile. Its small, irregular holes (known as “eyes”) are a hallmark of Danish cheese-making techniques, not Italian traditions. Pairing Havarti with Danish rye bread or using it in Scandinavian-inspired dishes like smørrebrød highlights its true cultural roots.

For those looking to avoid confusion, a simple rule of thumb is to examine the cheese’s label. Authentic Havarti will often include terms like “Danish-style” or “made in Denmark.” Additionally, its texture and flavor—milder and creamier than most Italian cheeses—can serve as a practical identifier. When in doubt, pair Havarti with Danish ingredients like dill, caraway, or apples to honor its origins, rather than defaulting to Italian combinations like basil and tomato.

In conclusion, while Havarti’s name may invite Italian associations, its history, production methods, and sensory qualities firmly root it in Denmark. By understanding these distinctions, cheese enthusiasts can appreciate Havarti not as an Italian imposter, but as a proud representative of Danish dairy craftsmanship. Next time you slice into a wheel of Havarti, remember: it’s not just a cheese—it’s a slice of Danish heritage.

Unveiling the Secret: What Meat Makes a Philly Cheesesteak Authentic?

You may want to see also

Italian Cheese Culture: Italy’s cheese tradition focuses on regional specialties, excluding Havarti

Havarti cheese, with its Danish origins, stands apart from Italy’s rich cheese tradition. Italy’s cheese culture is deeply rooted in regional identity, where each area takes pride in its unique specialties. From the creamy buffalo mozzarella of Campania to the sharp Parmigiano-Reggiano of Emilia-Romagna, Italian cheeses are a testament to local craftsmanship and terroir. Havarti, however, is conspicuously absent from this landscape, as Italy’s cheese heritage prioritizes indigenous varieties over foreign imports. This focus on regional specialties ensures that Italian cheeses remain distinct, reflecting centuries of tradition and local ingredients.

To understand why Havarti isn’t Italian, consider the principles of Italian cheese production. Italian cheeses are often protected by designations like DOP (Protected Designation of Origin), which strictly regulate their production methods and geographic origins. For example, Pecorino Romano must be made from sheep’s milk in specific regions of Lazio, Sardinia, and Tuscany. Havarti, on the other hand, is a semi-soft Danish cheese made from cow’s milk, with no ties to Italian traditions or regulations. This contrast highlights Italy’s commitment to preserving its culinary heritage, leaving no room for non-native cheeses like Havarti.

If you’re exploring Italian cheese culture, start by pairing regional cheeses with local wines and ingredients. For instance, enjoy a slice of Gorgonzola Dolce with a glass of Moscato d’Asti, or grate Grana Padano over a plate of handmade pasta. These combinations showcase the harmony between Italy’s cheeses and their regional counterparts. Havarti, while versatile, lacks this cultural context in Italy, making it an outlier in a tradition that values authenticity and locality.

A practical tip for cheese enthusiasts: when building an Italian cheese board, focus on diversity across regions. Include a hard cheese like Parmigiano-Reggiano, a soft cheese like Robiola, and a blue cheese like Gorgonzola. Avoid the temptation to add Havarti, as it would disrupt the board’s thematic coherence. Instead, use this opportunity to educate yourself and others about Italy’s regional specialties, reinforcing the idea that Italian cheese culture is a mosaic of local traditions, not a melting pot of global varieties.

In conclusion, Italy’s cheese tradition is a celebration of regional diversity, meticulously crafted to exclude non-native cheeses like Havarti. By embracing this exclusivity, Italy preserves its culinary identity, offering a rich tapestry of flavors that tell the story of its land and people. Havarti, while delightful in its own right, remains a reminder of the boundaries that define and protect Italy’s cherished cheese culture.

Creative Cheese Advertising: Strategies, Trends, and Consumer Engagement Techniques

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, Havarti cheese is not Italian. It is a Danish cheese that originated in Denmark.

Havarti cheese originated in Denmark in the mid-19th century and was named after the Havarthigaard farm.

While Havarti shares some characteristics with semi-soft Italian cheeses like Provolone, it is distinct in flavor and texture and is not Italian in origin.

Yes, Havarti can be used in Italian dishes as a substitute for cheeses like Mozzarella or Provolone, though it is not traditionally Italian.

Havarti is most comparable to Italian semi-soft cheeses like Fontina or young Provolone, but it remains a Danish cheese.