The question of whether lipase in cheese is vegetarian is a common concern for those following a plant-based diet. Lipase, an enzyme used in cheese production to break down fats, can be derived from both animal and microbial sources. While traditional lipases often come from animal stomachs, modern cheese-making increasingly uses microbial or plant-based alternatives, making many cheeses suitable for vegetarians. However, the source of lipase is not always clearly labeled, leaving consumers to research specific brands or opt for cheeses explicitly labeled as vegetarian or vegan to ensure alignment with their dietary preferences.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Source of Lipase | Lipase in cheese can be derived from microbial (bacterial or fungal), animal, or plant sources. Microbial lipases are commonly used in cheese production and are considered vegetarian-friendly. |

| Animal-Derived Lipase | Some traditional cheeses use lipases from animal sources (e.g., kid, calf, or lamb stomach lining), which are not vegetarian. However, these are less common in modern commercial cheese production. |

| Vegetarian Certification | Many cheeses labeled as "vegetarian" use microbial or plant-based lipases. Look for certifications like the Vegetarian Society Approved logo or similar to ensure compliance. |

| Common Cheeses with Vegetarian Lipase | Most mass-produced cheeses (e.g., cheddar, mozzarella, Swiss) use microbial lipases and are vegetarian. Artisanal or traditional cheeses may require verification. |

| Non-Vegetarian Cheeses | Cheeses like Pecorino Romano or traditional Parmesan often use animal-derived lipases and are not vegetarian. |

| Label Transparency | Not all cheese labels specify the source of lipase. Contacting the manufacturer or checking third-party certifications is recommended for clarity. |

| Alternative Enzymes | Plant-based lipases (e.g., from cinnamon or rice) are increasingly used in vegetarian cheese production. |

| Regional Variations | Regulations and practices vary by region. For example, EU-produced Parmesan alternatives often use microbial lipases to cater to vegetarians. |

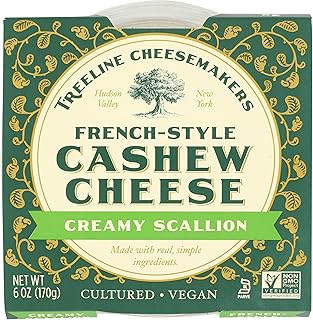

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Source of Lipase Enzyme: Animal or microbial origins determine if lipase in cheese is vegetarian-friendly

- Traditional Cheese Making: Historical use of animal-derived lipase in cheese production methods

- Vegetarian Alternatives: Microbial lipase as a plant-based substitute in modern cheese making

- Labeling and Certification: How vegetarian labels indicate the source of lipase in cheese products

- Common Cheeses to Avoid: List of cheeses typically made with animal-derived lipase for vegetarians

Source of Lipase Enzyme: Animal or microbial origins determine if lipase in cheese is vegetarian-friendly

Lipase, a crucial enzyme in cheese production, catalyzes the breakdown of fats, influencing texture and flavor. Its source, however, is pivotal for vegetarians. Derived from animals, such as calves or kids, lipase renders cheese non-vegetarian. Conversely, microbial lipase, sourced from fungi or bacteria, aligns with vegetarian and vegan diets. This distinction underscores the importance of scrutinizing cheese labels for lipase origin, ensuring dietary adherence.

Microbial lipases, often from *Aspergillus* or *Mucor* species, are widely used in industrial cheese-making due to their consistency and scalability. These enzymes are cultivated in controlled environments, free from animal involvement, making them a reliable vegetarian option. Manufacturers favoring microbial lipase can cater to broader markets, including those with dietary restrictions. For instance, European cheese producers increasingly adopt microbial alternatives to meet rising vegetarian demands, as evidenced by a 2021 study in the *Journal of Dairy Science*.

Animal-derived lipases, traditionally used in artisanal cheeses like Pecorino or Chèvre, pose challenges for vegetarians. These enzymes are extracted from the stomach linings of young ruminants, a practice rooted in centuries-old traditions. While they impart distinct flavors, their use limits the cheese’s appeal to non-vegetarian consumers. For vegetarians, identifying such cheeses requires vigilance, as labels often omit specific enzyme sources. A practical tip: look for certifications like "suitable for vegetarians" or inquire about production methods directly from artisanal producers.

The shift toward microbial lipases reflects evolving consumer preferences and technological advancements. Modern biotechnological methods enable the production of highly specific microbial enzymes, ensuring consistent quality without ethical concerns. For example, *Rhizopus* lipase is commonly used in mozzarella production, achieving optimal fat breakdown without animal derivatives. This trend aligns with global dietary shifts, as reported by the Food and Agriculture Organization, which notes a 25% increase in vegetarian-friendly cheese production over the past decade.

In conclusion, the source of lipase—animal or microbial—is the linchpin in determining whether cheese is vegetarian-friendly. While traditional methods rely on animal-derived enzymes, microbial alternatives offer an ethical, scalable solution. Consumers must remain informed, leveraging certifications and product inquiries to make aligned choices. As the industry adapts, microbial lipases are poised to dominate, bridging tradition and modernity in cheese-making.

Effortlessly Shred Cheese with Your Hamilton Beach Food Processor: A Guide

You may want to see also

Traditional Cheese Making: Historical use of animal-derived lipase in cheese production methods

The historical use of animal-derived lipase in traditional cheese making is deeply rooted in the quest for flavor complexity and texture enhancement. Lipase, an enzyme that breaks down fats into fatty acids, has been pivotal in creating the distinctive tang and creamy mouthfeel of certain cheeses. Historically, this enzyme was sourced from animal tissues, particularly the stomach linings of ruminants like goats, sheep, and cows. For instance, Pecorino Romano and Pepato cheeses traditionally incorporated lipase from lamb or kid goat stomachs, imparting their signature sharpness. This practice was not merely a culinary choice but a practical solution, leveraging readily available resources in pastoral communities.

Analyzing the process reveals a delicate balance of science and tradition. Animal-derived lipase was typically added during the curdling stage, often in precise dosages ranging from 0.05% to 0.2% of the milk weight. The enzyme’s activity was influenced by factors like temperature and pH, requiring skilled craftsmanship to avoid over-ripening or bitterness. For example, in the production of traditional Italian cheeses like Provolone, lipase was carefully measured to achieve the desired piquant flavor without overwhelming the milk’s natural sweetness. This method, though labor-intensive, ensured consistency and authenticity in the final product.

From a comparative perspective, animal-derived lipase stands in contrast to its microbial counterparts, which gained popularity in the 20th century. While microbial lipase offers uniformity and scalability, animal-derived lipase is celebrated for its nuanced flavor profile, often described as richer and more complex. However, this traditional approach raises ethical concerns for vegetarians and vegans, as it explicitly involves animal by-products. For those adhering to a plant-based diet, understanding the historical use of animal lipase underscores the importance of scrutinizing cheese labels or opting for explicitly vegetarian alternatives.

Practically, for home cheesemakers or enthusiasts, replicating traditional methods using animal-derived lipase requires sourcing specialized suppliers and adhering to strict hygiene standards. Modern regulations often restrict the use of raw animal tissues, necessitating pasteurized or processed lipase extracts. Dosage precision remains critical; over-addition can lead to rancidity, while under-addition may result in blandness. A tip for beginners: start with a lower dosage (e.g., 0.1% of milk weight) and adjust based on sensory evaluation during aging. This hands-on approach not only honors historical techniques but also fosters a deeper appreciation for the art of cheese making.

In conclusion, the historical use of animal-derived lipase in cheese production exemplifies the intersection of tradition, science, and ethics. While it remains a cornerstone of certain cheeses’ identity, its vegetarian-unfriendly nature prompts a reevaluation of modern practices. For consumers and producers alike, understanding this legacy enables informed choices, whether in preserving traditional methods or embracing innovative alternatives.

Exploring the Unexpectedly Queer Journey of Moving Cheese

You may want to see also

Vegetarian Alternatives: Microbial lipase as a plant-based substitute in modern cheese making

Lipase, a crucial enzyme in cheese making, traditionally derives from animal sources, raising concerns for vegetarians. However, microbial lipase offers a plant-based alternative, aligning with vegetarian dietary preferences. This enzyme, produced by microorganisms like fungi and bacteria, performs the same flavor-enhancing role as its animal counterpart without compromising ethical standards.

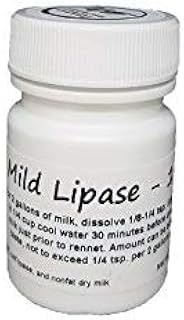

In modern cheese making, microbial lipase is typically added at a dosage of 0.05–0.1% of the milk weight, depending on the desired flavor intensity. For example, in Pecorino or Feta production, microbial lipase from *Aspergillus oryzae* or *Mucor miehei* is commonly used to achieve the characteristic sharp, tangy notes. To incorporate this alternative, cheese makers should dissolve the lipase in a small amount of warm water before adding it to the milk, ensuring even distribution.

One key advantage of microbial lipase is its consistency in performance compared to animal-derived lipase, which can vary based on the source. Additionally, it is shelf-stable and easier to standardize, making it a reliable choice for large-scale production. However, cheese makers must monitor pH and temperature carefully, as microbial lipase is sensitive to these factors and can over-ripen the cheese if misused.

For home cheese makers, microbial lipase is available in powdered form from specialty suppliers. Beginners should start with smaller dosages (e.g., 0.05% for mild flavors) and gradually increase based on taste preferences. Pairing microbial lipase with vegetarian rennet ensures the entire cheese-making process remains plant-based. This approach not only caters to vegetarians but also reduces reliance on animal-derived ingredients, promoting sustainability in the dairy industry.

In conclusion, microbial lipase is a versatile, ethical, and effective substitute for animal-derived lipase in cheese making. By adopting this alternative, producers can create vegetarian-friendly cheeses without sacrificing flavor or quality, meeting the growing demand for plant-based options in the market.

Astro Knights Cheese Hunt: Secret Locations Revealed for Players

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Labeling and Certification: How vegetarian labels indicate the source of lipase in cheese products

Vegetarian cheese labels often hinge on the source of lipase, an enzyme crucial for curdling milk. While lipase can be derived from plants (like cinnamon or flaxseed), animals (typically the stomach lining of ruminants), or through microbial fermentation, only the first two sources require explicit labeling. This distinction matters because vegetarians and vegans scrutinize ingredients for animal-derived additives. Certifications like the Vegetarian Society’s "V" or "Certified Vegan" logos typically ensure plant-based or microbial lipase, but generic "vegetarian" claims may lack transparency. Always check for specific certifications or contact manufacturers if unsure.

Analyzing labels requires understanding ingredient lists and certifications. For instance, "microbial lipase" or "plant-derived enzymes" explicitly indicate vegetarian-friendly sources. However, terms like "lipase" without qualifiers may originate from animals, particularly in traditional cheeses. European cheeses often use animal-derived lipase, while American or specialty brands increasingly opt for microbial alternatives. Look for third-party certifications like "Kosher Parve" or "Halal" as additional indicators, though these aren't foolproof. Cross-referencing with brand websites or databases like Barnivore can provide clarity when labels are ambiguous.

Persuasively, the push for transparent labeling benefits both consumers and producers. Clear indications of lipase sources build trust among vegetarian and vegan communities, expanding market reach. Brands like Daiya and Follow Your Heart exemplify this by explicitly stating microbial or plant-based enzymes in their products. Conversely, traditional cheesemakers risk alienating health-conscious or ethically driven consumers by omitting this information. Advocacy groups like PETA and the Vegan Society actively campaign for stricter labeling laws, emphasizing the growing demand for accountability.

Comparatively, European and American labeling standards differ significantly. The EU mandates allergen labeling but lacks specific requirements for enzyme sources, leaving vegetarians to decipher vague terms like "enzymes." In contrast, the USDA allows voluntary labeling of vegetarian products but doesn’t enforce consistency. India, with its large vegetarian population, has stricter norms, often requiring explicit declarations of animal-derived ingredients. These disparities highlight the need for global standardization to ensure informed choices across borders.

Descriptively, imagine a cheese label that reads: *"Microbial lipase (non-GMO), plant-based rennet, pasteurized milk."* This example offers clarity, assuring vegetarians of its suitability. Contrast this with a label stating *"Enzymes, salt, milk cultures,"* which leaves the lipase source ambiguous. Practical tips include prioritizing products with third-party certifications, avoiding traditional European cheeses unless verified, and using apps like Is It Vegan? to scan barcodes for instant ingredient analysis. By decoding labels thoughtfully, consumers can align their purchases with their dietary principles.

Mastering Nergigante: Effective Cheese Tactics for Monster Hunter Victory

You may want to see also

Common Cheeses to Avoid: List of cheeses typically made with animal-derived lipase for vegetarians

Vegetarians navigating the cheese aisle must scrutinize labels for animal-derived lipase, an enzyme often used in cheese production. While lipase can be sourced from plants or microbes, traditional methods frequently rely on animal stomach linings, particularly from calves, lambs, or goats. This makes certain cheeses off-limits for those adhering to a vegetarian diet. Understanding which cheeses typically contain animal-derived lipase is crucial for making informed choices.

Analyzing the Culprits:

Cheeses like Pecorino Romano, Parmigiano-Reggiano, and Grana Padano are prime examples of varieties traditionally made with animal-derived lipase. These hard, aged cheeses owe their distinctive sharp flavors to the enzyme’s role in breaking down fats during maturation. Similarly, some varieties of Provolone and Pepato also fall into this category. While not all producers use animal-derived lipase, the risk is high enough to warrant caution unless explicitly labeled otherwise.

Practical Tips for Identification:

To avoid animal-derived lipase, look for certifications like "vegetarian" or "microbial enzymes" on cheese packaging. Artisanal or imported cheeses are more likely to use traditional methods, so domestic or mass-produced options may be safer bets. When in doubt, contact the manufacturer directly for clarification. Apps and websites that track vegetarian-friendly products can also streamline your shopping process.

Comparing Alternatives:

Fortunately, many cheeses are naturally vegetarian-friendly or use microbial lipase. Mozzarella, Cheddar, Gouda, and Swiss cheese are typically safe choices, as are most soft cheeses like Brie and Camembert. Plant-based lipase is increasingly common in modern production, making it easier to find ethical alternatives. By prioritizing transparency and research, vegetarians can enjoy a diverse cheese selection without compromising their dietary principles.

Why TSA Asks About Cheese: Unpacking the Unexpected Security Question

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, lipase in cheese can be derived from both animal and microbial (bacterial or fungal) sources. Vegetarian-friendly lipase is typically microbial.

Check the label for terms like "microbial lipase," "vegetarian enzymes," or certifications such as "suitable for vegetarians." If unsure, contact the manufacturer.

Not necessarily. Many cheeses use microbial lipase, which is vegetarian. However, traditional cheeses like Parmesan often use animal-derived lipase, so it’s important to verify.

Yes, many brands offer vegetarian cheeses that use microbial lipase. Look for labels indicating "vegetarian" or "microbial enzymes" to ensure it meets your dietary needs.