Making cheese from milk is often considered a chemical change due to the transformation of milk's molecular structure through processes like curdling and coagulation. When milk is exposed to acids, rennet, or bacteria, proteins such as casein rearrange and bind together, forming curds and releasing whey. This irreversible alteration in the composition and properties of milk results in a new substance—cheese—with distinct characteristics, texture, and flavor. Unlike physical changes, where the substance’s identity remains unchanged, the chemical reactions involved in cheesemaking fundamentally modify the milk, making it a clear example of a chemical change.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Type of Change | Chemical Change |

| Reason | Involves the coagulation of milk proteins (casein) and the formation of new substances (curds and whey) through the action of enzymes (e.g., rennet) or acids. |

| Molecular Alteration | Yes, new chemical bonds are formed, and the structure of milk proteins changes. |

| Reversibility | No, the process is irreversible; cheese cannot be turned back into milk. |

| Energy Change | Minimal heat is often applied, but the primary change is due to chemical reactions, not heat. |

| Formation of New Substances | Yes, curds (solid cheese) and whey (liquid) are formed, which are distinct from the original milk. |

| pH Change | Yes, the pH of milk decreases due to the addition of acids or enzymes, aiding in coagulation. |

| Examples of Chemical Reactions | Proteolysis (breakdown of proteins), coagulation, and syneresis (expulsion of whey). |

| Scientific Consensus | Widely accepted as a chemical change due to the irreversible transformation of milk into cheese. |

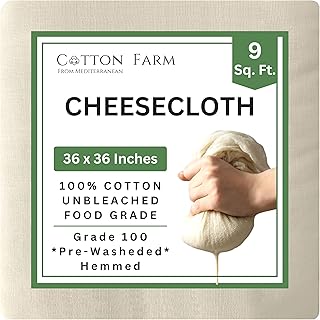

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Curdling Process: Enzymes break milk proteins, forming curds and whey, a key chemical transformation

- Acidification Role: Lactic acid bacteria lower pH, altering milk structure chemically

- Coagulation Mechanism: Rennet enzymes convert liquid milk into solid curds irreversibly

- Fermentation Impact: Microbial activity produces new compounds, changing milk chemically

- Irreversibility Proof: Curds cannot revert to milk, confirming a chemical change

Curdling Process: Enzymes break milk proteins, forming curds and whey, a key chemical transformation

The curdling process is a fascinating chemical transformation where enzymes, such as rennet or bacterial cultures, break down milk proteins, primarily casein, into curds and whey. This reaction is not merely a physical separation but a fundamental alteration in the molecular structure of milk. When rennet, for instance, is added at a typical dosage of 0.02% to 0.05% of the milk’s weight, it activates protease enzymes that cleave κ-casein, destabilizing the milk’s micellar structure. This destabilization causes the casein proteins to aggregate, forming solid curds, while the liquid whey, rich in lactose and minerals, separates out. Understanding this mechanism is crucial for cheese makers, as it dictates texture, flavor, and yield.

From a practical standpoint, mastering the curdling process requires precision and attention to detail. Temperature plays a critical role, with most enzymes functioning optimally between 30°C and 35°C (86°F to 95°F). Deviations from this range can slow or halt the reaction, leading to incomplete curd formation. For home cheese makers, using a thermometer to monitor temperature is essential. Additionally, the type of enzyme used matters: animal rennet works quickly but may not suit vegetarians, while microbial rennet offers a plant-based alternative with slightly different curdling kinetics. Experimenting with dosages and timing allows for customization of cheese texture, from soft and creamy to firm and crumbly.

Comparatively, the curdling process in cheese making shares similarities with other enzymatic reactions in food production, such as beer brewing or yogurt fermentation. However, its uniqueness lies in the dual outcome of curds and whey, both of which have distinct culinary applications. While whey is often discarded in traditional cheese making, modern practices repurpose it into protein powders, ricotta, or animal feed, minimizing waste. This highlights the curdling process as not just a chemical transformation but also a sustainable practice in food production.

Descriptively, witnessing the curdling process is akin to observing a delicate dance of molecules. Within minutes of enzyme addition, the once-homogeneous milk begins to thicken, and a clear boundary forms between the solid curds and liquid whey. The curds, initially soft and gelatinous, gradually firm up as more water is expelled. This visual and textural evolution underscores the irreversible nature of the chemical change, as the milk’s original properties are permanently altered. For cheese enthusiasts, this stage is both a scientific marvel and an artistic beginning, setting the foundation for the cheese’s final character.

In conclusion, the curdling process is a cornerstone of cheese making, driven by enzymes that catalyze a profound chemical transformation. By breaking milk proteins into curds and whey, it not only creates the base for cheese but also exemplifies the intersection of biochemistry and culinary art. Whether you’re a novice or an expert, understanding and controlling this process unlocks endless possibilities for crafting unique cheeses. With the right tools, knowledge, and creativity, anyone can turn a simple glass of milk into a complex, flavorful masterpiece.

Unraveling the Cheesy Puzzle: What’s the Geometry of Borrowed Cheese?

You may want to see also

Acidification Role: Lactic acid bacteria lower pH, altering milk structure chemically

Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) are the unsung heroes of cheese making, driving a chemical transformation that turns liquid milk into a solid, flavorful cheese. These microorganisms, naturally present in milk or added as starter cultures, metabolize lactose (milk sugar) and produce lactic acid as a byproduct. This process, known as acidification, lowers the pH of the milk, triggering a cascade of chemical and structural changes. For instance, a pH drop from 6.6 to around 5.0 causes milk proteins (primarily casein) to lose their negative charge, reducing repulsion between molecules and allowing them to aggregate. This aggregation is the foundation of curd formation, a critical step in cheese making.

Consider the precision required in this process. Too little acidification, and the curd remains weak and unstable; too much, and the proteins denature excessively, leading to a grainy texture. Starter cultures are often dosed at 1–2% of milk volume, depending on the cheese variety and desired acidity. For example, in cheddar production, a mesophilic culture is added at a rate of 0.5–1.0% to achieve a final pH of 5.2–5.4. Monitoring pH with a digital meter ensures consistency, as deviations of even 0.1 units can significantly impact texture and flavor. This delicate balance highlights the chemical precision inherent in cheese making.

From a comparative perspective, acidification in cheese making mirrors processes in other fermented foods like yogurt and sauerkraut, where LAB also lower pH to preserve and transform raw materials. However, cheese making involves an additional step: coagulation, often induced by rennet or microbial transglutaminase. While rennet cleaves kappa-casein to form a gel, acidification alone can produce fresh cheeses like cottage cheese or queso fresco. The synergy between acidification and coagulation in harder cheeses like cheddar or gouda underscores the complexity of chemical changes in dairy transformation.

Practically, home cheese makers can harness acidification by controlling temperature and time. Mesophilic cultures thrive at 20–30°C (68–86°F), while thermophilic cultures require 35–45°C (95–113°F). For a simple acid-set cheese, heat milk to 30°C, add culture, and maintain the temperature for 12–24 hours until the pH reaches 4.6. Avoid stirring excessively, as this disrupts protein aggregation. Once curds form, cut and drain them gently to preserve moisture and texture. This hands-on approach demystifies the chemical role of LAB, making cheese making both a science and an art.

In conclusion, the acidification driven by lactic acid bacteria is not merely a step in cheese making but a chemical masterstroke. By lowering pH, LAB alter milk’s structure at a molecular level, enabling curd formation and flavor development. Whether in industrial production or home kitchens, understanding this process empowers cheese makers to control outcomes with precision. It’s a testament to how microbiology and chemistry converge to transform a humble ingredient into a culinary treasure.

Animal Style In-N-Out: Is the Cheesy Secret Menu Worth It?

You may want to see also

Coagulation Mechanism: Rennet enzymes convert liquid milk into solid curds irreversibly

The transformation of liquid milk into solid curds is a fascinating process that hinges on the action of rennet enzymes. These enzymes, derived from the stomach lining of ruminant animals, play a pivotal role in cheese making by catalyzing the coagulation of milk proteins. Specifically, rennet contains chymosin, an enzyme that selectively cleaves kappa-casein, a protein stabilizing milk’s liquid structure. Once kappa-casein is split, the remaining casein proteins aggregate, trapping fat and other milk components into a solid mass—the curd. This reaction is irreversible, as the proteins cannot revert to their original, dispersed state. Understanding this mechanism is crucial for cheese makers, as it dictates the texture, yield, and quality of the final product.

To achieve optimal coagulation, precise control over rennet dosage and milk conditions is essential. Typically, 0.02–0.05% of liquid rennet (or 0.005–0.01% of powdered rennet) is added to milk, depending on its pH, temperature, and protein content. Milk should be heated to 30–35°C (86–95°F), as this range activates rennet enzymes while preserving their efficacy. Adding rennet too early or at higher temperatures can denature the enzymes, while lower temperatures slow the reaction excessively. For home cheese makers, using a thermometer and measuring tools ensures consistency. Commercial producers often employ standardized protocols, adjusting dosages based on milk batch variability.

Comparing rennet coagulation to other methods, such as acidification with vinegar or lemon juice, highlights its unique advantages. Acid-induced coagulation relies on lowering milk’s pH, causing proteins to denature and precipitate. While simpler, this method produces softer, more fragile curds and is less suitable for aged cheeses. Rennet, in contrast, creates a firmer, more elastic curd ideal for stretching, pressing, and aging. This distinction underscores why rennet is preferred in traditional cheese making, particularly for varieties like cheddar, mozzarella, and Parmesan. However, vegetarians and those seeking alternatives can use microbial or plant-based coagulants, which mimic rennet’s action but may yield slightly different results.

Practical tips for mastering rennet-induced coagulation include monitoring milk quality and freshness, as older milk may contain bacteria that interfere with enzyme activity. Stirring rennet gently but thoroughly ensures even distribution, preventing uneven curd formation. After adding rennet, allowing the milk to rest undisturbed for 30–60 minutes facilitates complete coagulation. Testing for a "clean break"—where the curd separates cleanly from the whey when cut—confirms the reaction’s success. If the curd remains soft or weepy, adjusting rennet dosage or milk temperature in subsequent batches can improve outcomes. By mastering these nuances, cheese makers can harness the coagulation mechanism to craft cheeses with desired textures and flavors.

Fiber Content in 1oz American Cheese: Surprising Facts Revealed

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Fermentation Impact: Microbial activity produces new compounds, changing milk chemically

Microbial fermentation is the cornerstone of transforming milk into cheese, a process that undeniably qualifies as a chemical change. When lactic acid bacteria, such as *Lactococcus lactis*, are introduced to milk, they metabolize lactose (milk sugar) into lactic acid. This acidification lowers the milk’s pH, causing casein proteins to coagulate and form curds. But fermentation doesn’t stop there—it produces additional compounds like diacetyl, which contributes the buttery flavor in cheeses like Cheddar, and propionic acid, responsible for the eye formation in Swiss cheese. These new compounds are not present in raw milk, proving that fermentation chemically alters its composition.

To harness fermentation effectively, precise control over microbial activity is essential. For example, in the production of blue cheese, *Penicillium roqueforti* spores are added at a rate of 10^6 to 10^8 colony-forming units per milliliter of milk. This dosage ensures even mold growth without overwhelming the cheese’s texture. Similarly, in aged cheeses like Parmesan, starter cultures are combined with propionic acid bacteria at a ratio of 1:0.1 to balance flavor development and eye formation. Monitoring temperature (typically 20–30°C) and humidity during aging further optimizes microbial activity, ensuring consistent chemical transformations.

The chemical changes driven by fermentation extend beyond flavor and texture—they also enhance nutritional profiles and safety. Fermentation breaks down lactose, making cheese more digestible for lactose-intolerant individuals. Additionally, antimicrobial compounds like bacteriocins, produced by certain bacteria, inhibit pathogens such as *Listeria monocytogenes*. For instance, nisin, a bacteriocin produced by *Lactococcus lactis*, is approved as a food preservative (E234) and is naturally present in fermented dairy products. This dual benefit of fermentation—improving both sensory qualities and safety—underscores its chemical impact.

Comparing fermented and non-fermented dairy products highlights the extent of these chemical changes. While yogurt and kefir undergo similar microbial transformations, their shorter fermentation periods result in milder flavor profiles and higher lactose content compared to aged cheeses. In contrast, non-fermented products like paneer or ricotta rely solely on acid or heat coagulation, retaining much of milk’s original chemical composition. Cheese, however, undergoes prolonged fermentation and aging, creating a complex matrix of proteins, fats, and bioactive compounds that are chemically distinct from its starting material.

For home cheesemakers, understanding fermentation’s chemical impact is key to troubleshooting common issues. If curds fail to set, it may indicate insufficient lactic acid production due to low bacterial activity or high milk pH. Adding a pinch of calcium chloride (1–2% of milk weight) can strengthen curd formation, but over-acidification can lead to bitter flavors or crumbly textures. Similarly, mold growth in aged cheeses should be monitored—while desirable in blue cheeses, it can spoil others if not controlled. Regularly turning and brushing cheese during aging prevents unwanted microbial activity, ensuring the desired chemical transformations occur.

Does Salt Harm Milk Kefir Cheese Probiotics? Uncovering the Truth

You may want to see also

Irreversibility Proof: Curds cannot revert to milk, confirming a chemical change

Curds, once formed during the cheese-making process, cannot be transformed back into milk. This irreversibility is a hallmark of chemical changes, where substances undergo transformations that alter their fundamental properties. When milk is coagulated by enzymes like rennet or acids, proteins such as casein rearrange and bond to form a solid mass—curds. This process involves the breaking and forming of chemical bonds, creating new compounds that are structurally and functionally distinct from the original milk proteins. Attempting to reverse this by dissolving curds in water or reheating them only results in a soupy, denatured mess, not milk. This inability to revert to the original state is a clear indicator that a chemical change has occurred.

To understand this irreversibility, consider the molecular level. Milk proteins are suspended in a colloidal solution, where they remain dispersed due to their charge and hydration shell. During curdling, these proteins lose their charge and aggregate, driven by enzymatic or acidic action. This aggregation is not a simple mixing or separation process but a reconfiguration of protein structures. For instance, rennet hydrolyzes κ-casein, removing its hydrophilic tail and allowing micelles to coalesce into curds. Reversing this would require breaking the newly formed bonds and restoring the original protein conformation, which is thermodynamically unfavorable and practically impossible without destroying the protein’s integrity.

A practical experiment illustrates this point: take 1 cup of fresh curds and attempt to reconstitute them into milk by blending with 2 cups of water at room temperature. Despite thorough mixing, the curds remain insoluble, and the liquid appears cloudy and grainy. Heating the mixture to 60°C (140°F) for 10 minutes further denatures the proteins, making them even less soluble. This simple test confirms that curds cannot be "unmade" into milk, reinforcing the chemical nature of the transformation. For educators or curious individuals, this experiment serves as a tangible demonstration of irreversibility in chemical changes.

From a comparative perspective, consider physical changes like dissolving salt in water. Here, the salt dissociates into ions but can be fully recovered by evaporation, as no new substances are formed. In contrast, cheese-making involves the creation of new compounds—curds—that cannot be reverted to milk. This distinction is crucial in chemistry education, as it teaches students to identify chemical changes by their irreversible nature. For instance, in a classroom setting, comparing the reversibility of dissolving sugar in water (physical change) with the irreversibility of curdling milk (chemical change) can deepen understanding of these concepts.

In conclusion, the irreversibility of curds reverting to milk provides definitive proof that cheese-making involves a chemical change. This principle is not just theoretical but can be demonstrated through simple experiments and molecular analysis. By focusing on this specific aspect, one gains a deeper appreciation for the transformative processes in food chemistry and the broader principles of chemical changes. Whether in a lab, kitchen, or classroom, this understanding highlights the profound difference between physical and chemical transformations, making it a valuable lesson in both science and culinary arts.

Milk to Cheese Conversion: How Many Gallons Make a Pound?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, making cheese from milk involves chemical changes, as proteins in milk (casein) coagulate and undergo structural transformations when enzymes or acids are added.

The addition of rennet or acid causes milk proteins to curdle, forming curds and whey, and enzymes break down lactose into lactic acid, altering the milk’s chemical composition.

Yes, the molecular structure of milk proteins changes during cheese making, as they aggregate and form a solid matrix, which is chemically distinct from liquid milk.

The separation of curds and whey is primarily a chemical change, as it results from the coagulation of milk proteins, not just a physical separation.

Rennet or acid triggers the chemical reaction that causes milk proteins to coagulate, which is essential for transforming milk into cheese.