When it comes to cheese, mold is often the first concern that comes to mind, but it’s far from the only potential issue. While some molds are harmless or even desirable, such as those found in blue cheese or Brie, others can produce harmful mycotoxins. However, cheese can also harbor bacteria like Listeria, Salmonella, or E. coli, especially if improperly stored or handled. Additionally, factors like age, type, and packaging play a role in safety. Understanding these risks and knowing how to identify spoiled cheese—whether through mold, off odors, or texture changes—is essential for enjoying this beloved food safely.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Mold Presence | Common on certain cheeses (e.g., blue cheese, Brie); not always harmful but can indicate spoilage. |

| Other Contaminants | Bacteria (e.g., Listeria, Salmonella), yeast, and toxins (e.g., aflatoxins) can also be present. |

| Hard vs. Soft Cheese | Hard cheeses (e.g., Cheddar) are less likely to spoil due to lower moisture content; soft cheeses (e.g., Camembert) are more prone to contamination. |

| Storage Conditions | Improper storage (e.g., high humidity, warm temperatures) accelerates spoilage and mold growth. |

| Health Risks | Moldy cheese can cause allergic reactions, respiratory issues, or food poisoning, especially in immunocompromised individuals. |

| Safe Practices | Remove mold from hard cheeses if it’s superficial; discard soft cheeses with mold. Always follow storage guidelines. |

| Common Misconceptions | Not all molds are safe; some produce harmful mycotoxins even if not visible. |

| Prevention | Store cheese properly (refrigerated, wrapped in wax or parchment paper) and consume within recommended timeframes. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Other Cheese Contaminants: Bacteria, yeast, and allergens can also pose risks beyond mold

- Safe Mold Types: Some molds are harmless or even desirable, like in blue cheese

- Spoilage Signs: Off odors, sliminess, or discoloration indicate cheese is unsafe to eat

- Storage Practices: Proper refrigeration and packaging reduce mold and other spoilage risks

- Health Risks: Moldy cheese can cause allergies, respiratory issues, or food poisoning in some cases

Other Cheese Contaminants: Bacteria, yeast, and allergens can also pose risks beyond mold

While mold often steals the spotlight in cheese safety discussions, it’s far from the only culprit. Bacteria like *Listeria monocytogenes* and *Salmonella* can thrive in cheese, particularly soft, unpasteurized varieties. Listeria, for instance, poses a severe risk to pregnant women, newborns, the elderly, and immunocompromised individuals, potentially causing miscarriages, sepsis, or meningitis. A single serving of contaminated cheese can introduce enough pathogens to trigger illness, especially if stored improperly. Unlike mold, which is often visible, these bacteria are invisible, making them more insidious. Always check labels for pasteurization, as this process eliminates many harmful bacteria, and store cheese at or below 40°F (4°C) to slow bacterial growth.

Yeast, though less commonly discussed, can also contaminate cheese, particularly during production or storage. Certain yeast species, such as *Yarrowia lipolytica*, can produce toxins or cause spoilage, altering flavor and texture. While not typically life-threatening, yeast contamination can render cheese unpalatable or even unsafe for consumption, especially in individuals with yeast sensitivities. Artisanal or homemade cheeses are more susceptible due to less controlled environments. To minimize risk, inspect cheese for unusual odors (like a strong, alcoholic scent) or slimy textures, which may indicate yeast overgrowth. Proper wrapping and refrigeration are key to preventing yeast proliferation.

Allergens in cheese are another critical concern, often overlooked in food safety conversations. Milk proteins like casein and whey are common allergens, affecting up to 2-3% of children and 0.5% of adults globally. Even trace amounts in cross-contaminated products can trigger severe reactions, including anaphylaxis. Additionally, additives like annatto (a coloring agent) or microbial transglutaminase (a binding enzyme) can cause sensitivities in some individuals. Always read labels carefully, especially for processed or flavored cheeses, and consider allergen-free alternatives like plant-based cheeses for vulnerable populations.

Practical steps can mitigate these risks. First, prioritize pasteurized cheese, especially for pregnant women, children under 5, and those with weakened immune systems. Second, maintain strict hygiene during handling—wash hands, utensils, and surfaces to prevent cross-contamination. Third, adhere to storage guidelines: hard cheeses last 3-4 weeks, while soft cheeses should be consumed within a week. Finally, trust your senses—discard cheese with off-putting smells, colors, or textures, even if mold isn’t visible. By broadening our focus beyond mold, we can enjoy cheese safely while minimizing hidden dangers.

Carb Count in Cheese: Unveiling the Surprising Truth

You may want to see also

Safe Mold Types: Some molds are harmless or even desirable, like in blue cheese

Not all molds are created equal, and this is particularly evident in the world of cheese. While discovering mold on food typically signals a trip to the trash, certain cheeses proudly showcase mold as a defining feature. Blue cheese, for instance, owes its distinctive flavor and appearance to the intentional introduction of Penicillium molds during production. These molds, specifically Penicillium roqueforti and Penicillium camemberti, are not only safe for consumption but are celebrated for the complex flavors and textures they impart. Unlike harmful molds that can produce toxic substances, these strains are carefully cultivated and controlled, ensuring they remain beneficial rather than hazardous.

The safety of these molds lies in their specific strains and the controlled environment in which they are grown. For example, Penicillium roqueforti, used in blue cheeses like Roquefort and Gorgonzola, thrives in the cool, humid conditions of aging caves. This mold produces mycotoxins in minimal, harmless quantities under these conditions, while its metabolic byproducts contribute to the cheese’s tangy, pungent profile. Similarly, Penicillium camemberti, used in Camembert and Brie, creates a soft, edible rind that enhances the cheese’s creamy interior. Understanding these processes allows consumers to appreciate moldy cheeses without fear, as long as they are produced under regulated conditions.

However, not all cheeses with mold are safe to eat. Hard cheeses like cheddar or Parmesan, when moldy, should be discarded entirely or cut away with a one-inch margin around the moldy spot, as the mold can penetrate deeper than visible. Soft cheeses, on the other hand, should be thrown out if mold appears, as their high moisture content allows mold to spread quickly. The key distinction is whether the mold is part of the cheese’s intended production or an unintended contaminant. Always check labels or consult experts if unsure, as misidentifying mold can lead to foodborne illnesses.

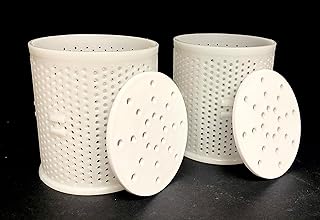

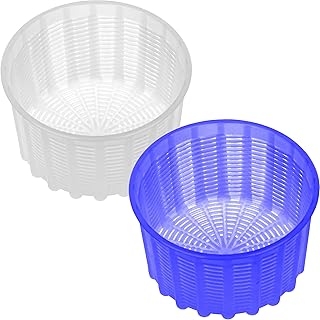

For those who enjoy mold-ripened cheeses, proper storage is crucial to maintaining safety and quality. Keep these cheeses in the refrigerator, wrapped in wax or parchment paper to allow breathing while preventing mold overgrowth. Avoid plastic wrap, as it traps moisture and encourages spoilage. When serving, use clean utensils to prevent cross-contamination, and consume the cheese within recommended timeframes. For example, a wheel of Brie should be eaten within two weeks of purchase, while harder blue cheeses can last up to six months if stored correctly. By following these guidelines, you can safely enjoy the unique flavors of mold-ripened cheeses without worry.

In conclusion, while mold on cheese often raises alarm, certain molds are not only safe but essential to the character of specific cheeses. By understanding which molds are intentional and how they function, consumers can confidently distinguish between desirable and dangerous mold. Always prioritize knowledge and proper handling to ensure a safe and enjoyable cheese experience. Whether savoring a crumbly Roquefort or a creamy Camembert, the right mold can transform cheese from a simple food into a culinary masterpiece.

Perfectly Preserving Homemade Cheese and Bacon Rolls: Storage Tips and Tricks

You may want to see also

Spoilage Signs: Off odors, sliminess, or discoloration indicate cheese is unsafe to eat

Cheese, a beloved staple in many diets, can sometimes turn from a culinary delight into a potential health hazard. While mold is a well-known culprit, it’s not the only sign of spoilage. Off odors, sliminess, or discoloration are equally critical indicators that your cheese has crossed the line from edible to unsafe. These signs often signal bacterial growth or chemical changes that can cause foodborne illnesses, making it essential to recognize them promptly.

Let’s start with off odors. Fresh cheese should have a pleasant, characteristic scent—whether mild, tangy, or sharp. If your cheese emits an ammonia-like, sour, or putrid smell, it’s a red flag. This odor typically arises from the breakdown of proteins by bacteria, which can produce harmful compounds. For example, a strong, unpleasant smell in soft cheeses like Brie or Camembert often indicates spoilage, even if visible mold isn’t present. Trust your nose: if it smells off, toss it out.

Sliminess is another unmistakable sign of spoilage, particularly in hard or semi-hard cheeses like Cheddar or Swiss. A healthy cheese surface should be dry or slightly moist, depending on the type. If you notice a sticky, slippery film, it’s likely due to bacterial overgrowth or excess moisture. This sliminess can occur even in refrigerated cheese, especially if it’s been improperly stored or left unwrapped. Soft cheeses naturally have a higher moisture content, but any unusual stickiness beyond their typical texture is a warning sign.

Discoloration, though sometimes harmless, can also indicate spoilage. While some cheeses naturally develop surface mold as part of their aging process (e.g., blue cheese), unexpected color changes—like pink, yellow, or black spots on cheeses that shouldn’t have them—suggest bacterial or fungal contamination. For instance, orange or pink discoloration on white cheeses like mozzarella or feta often points to Pseudomonas bacteria, which can cause gastrointestinal issues. Similarly, dark spots on hard cheeses may indicate mold penetration beyond the surface, rendering the entire piece unsafe.

To minimize the risk of consuming spoiled cheese, follow these practical tips: store cheese in the coldest part of your refrigerator (below 40°F or 4°C), wrap it in wax or parchment paper to allow breathing while preventing moisture buildup, and avoid plastic wrap, which traps humidity. Regularly inspect cheese for spoilage signs, especially if it’s past its prime. When in doubt, err on the side of caution—no cheese is worth risking food poisoning. By staying vigilant to off odors, sliminess, and discoloration, you can enjoy cheese safely and savor its flavors without worry.

Taco Bell Chili Cheese Burrito: Beans or No Beans Inside?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Storage Practices: Proper refrigeration and packaging reduce mold and other spoilage risks

Mold is often the first sign of cheese spoilage, but it’s far from the only culprit. Bacteria, yeast, and chemical reactions can also degrade texture, flavor, and safety. Proper storage practices—specifically refrigeration and packaging—are critical to slowing these processes. Refrigeration maintains temperatures between 35°F and 40°F (2°C and 4°C), which inhibits microbial growth and enzymatic activity. Packaging, whether wax paper, parchment, or specialized cheese wrap, creates a barrier against moisture loss and external contaminants. Together, these methods extend shelf life and preserve quality, ensuring cheese remains safe and enjoyable.

Consider the role of humidity in cheese storage, a factor often overlooked. Hard cheeses like Parmesan thrive in drier conditions, while soft cheeses like Brie require higher humidity to prevent drying. Refrigerators, inherently dry environments, can be modified with cheese storage drawers or humidity-controlled containers. For example, wrapping soft cheese in wax paper followed by a loose plastic bag maintains moisture without promoting mold. Hard cheeses benefit from airtight containers that minimize exposure to air. These tailored approaches demonstrate how precise storage practices address specific spoilage risks beyond mold.

Improper packaging can accelerate spoilage faster than temperature alone. Cling film, a common household item, traps moisture against cheese, fostering mold growth. Instead, opt for breathable materials like wax paper or cheese paper, which allow gases to escape while retaining enough humidity. Vacuum-sealed packaging is ideal for long-term storage, as it removes oxygen that promotes bacterial growth. For pre-sliced cheese, individual wraps prevent cross-contamination and moisture absorption. These packaging choices, combined with refrigeration, create a dual defense against spoilage, ensuring cheese retains its intended characteristics.

A comparative analysis reveals the impact of storage practices on different cheese types. Blue cheese, already mold-ripened, requires careful packaging to prevent excess moisture from diluting its flavor. In contrast, fresh cheeses like mozzarella are highly perishable and demand airtight containers to slow bacterial spoilage. Aged cheeses, such as Cheddar, benefit from wax coatings that minimize air exposure and moisture loss. Each type highlights how tailored storage—specific temperatures, humidity levels, and packaging—mitigates risks beyond mold. By understanding these nuances, consumers can maximize cheese longevity and quality.

Finally, practical tips can transform storage practices into everyday habits. Always store cheese in the coldest part of the refrigerator, typically the lower back shelves, to maintain consistent temperatures. Label packages with purchase dates to track freshness, discarding cheese after recommended durations (e.g., soft cheese within 1-2 weeks, hard cheese within 3-4 weeks). Avoid overwrapping, as excess layers can trap moisture and heat. For partially used cheese, rewrap tightly and consume promptly. These simple yet effective strategies reduce spoilage risks, ensuring mold is the least of your worries when enjoying cheese.

Shredded Cheese Points on Weight Watchers: A Simple Guide

You may want to see also

Health Risks: Moldy cheese can cause allergies, respiratory issues, or food poisoning in some cases

Mold on cheese isn’t always a benign sign of aging. While some cheeses, like Brie or Stilton, intentionally cultivate specific molds for flavor, unintended mold growth can introduce health risks. The type of mold matters—common household molds like *Aspergillus* or *Penicillium* can produce mycotoxins, harmful substances that aren’t destroyed by digestion. Ingesting these toxins, even in small amounts, can lead to acute food poisoning symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. For instance, aflatoxins, produced by certain molds, are among the most carcinogenic substances known, though they’re more commonly associated with grains and nuts. Still, the risk exists, particularly with improperly stored cheese.

Allergies are another concern, especially for individuals sensitive to mold spores. Inhaling or ingesting mold on cheese can trigger allergic reactions ranging from mild, like sneezing or skin rashes, to severe, such as anaphylaxis. Children, the elderly, and those with compromised immune systems are particularly vulnerable. For example, a study published in the *Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology* found that mold exposure, including from contaminated foods, exacerbated asthma symptoms in 30% of participants. If you suspect mold-related allergies, removing moldy cheese from your diet and consulting an allergist is crucial.

Respiratory issues can arise from handling moldy cheese, even if you don’t consume it. Cutting or touching contaminated cheese releases spores into the air, which can be inhaled and irritate the lungs. This is especially problematic for individuals with pre-existing respiratory conditions like asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). A practical tip: if you discover mold on cheese, dispose of it in a sealed bag to minimize spore release, and clean the storage area with a vinegar solution to kill residual mold.

Prevention is key to avoiding these health risks. Store cheese properly—hard cheeses like cheddar should be wrapped in wax or parchment paper, while soft cheeses need airtight containers. Refrigerate all cheese at or below 40°F (4°C) to slow mold growth. If mold appears, discard the entire piece if it’s a soft cheese, as spores can penetrate deeply. For hard cheeses, cut off the moldy portion plus an additional inch around it, but only if the cheese is still safe to consume. When in doubt, throw it out—the risk of illness outweighs the cost of replacement.

Finally, education is essential. Not all molds are created equal, and knowing the difference between safe and harmful varieties can protect your health. For instance, the white mold on Brie is safe and part of its character, but green or black mold on any cheese is a red flag. Stay informed, follow storage guidelines, and trust your instincts—if something looks or smells off, it’s better to err on the side of caution.

Can Dota Mid Bot Be Beaten Without Cheese? A Deep Dive

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, while mold is a common concern, other issues like bacterial contamination (e.g., Listeria, Salmonella), improper storage, and expiration dates can also pose risks.

It depends on the type of cheese. For hard cheeses like cheddar, cutting off mold plus an inch around it is generally safe. However, soft cheeses like Brie or cottage cheese should be discarded entirely if moldy.

Not necessarily. Some cheeses, like blue cheese or Camembert, have intentional mold as part of their flavor profile. However, unintended mold on other types of cheese can indicate spoilage.

Yes, consuming moldy cheese can cause allergic reactions, respiratory issues, or food poisoning, especially in individuals with weakened immune systems or mold sensitivities. Always err on the side of caution.