Paneer and cheese are often confused due to their similar appearances and roles in cooking, but they are distinct dairy products with unique characteristics. Paneer, a staple in Indian cuisine, is a fresh, unsalted cheese made by curdling milk with an acidic agent like lemon juice or vinegar, then pressing the curds to form a soft, crumbly block. Unlike aged cheeses, paneer is not fermented or ripened, giving it a mild, milky flavor and a firm yet tender texture. Cheese, on the other hand, is a broader category of dairy products that undergo processes like fermentation, aging, and sometimes the addition of cultures or rennet, resulting in a wide variety of flavors, textures, and types, from soft cheeses like mozzarella to hard cheeses like cheddar. While paneer can be considered a type of cheese, its simplicity and lack of aging set it apart from the diverse world of cheeses found globally.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Origin | Paneer: Originated in the Indian subcontinent; Cheese: Originated in the Middle East and Europe. |

| Ingredients | Paneer: Made from milk, lemon juice/vinegar, and sometimes rennet; Cheese: Made from milk, rennet, and bacterial cultures. |

| Texture | Paneer: Firm, crumbly, and unsalted; Cheese: Varies widely (soft, semi-soft, hard, etc.), often salted. |

| Flavor | Paneer: Mild, milky, and neutral; Cheese: Diverse flavors (sharp, nutty, tangy, etc.) depending on type. |

| Production | Paneer: Coagulated with acid (e.g., lemon juice) and not aged; Cheese: Coagulated with rennet and often aged. |

| Usage | Paneer: Primarily used in Indian cuisine (curries, snacks); Cheese: Used globally in various dishes (pizzas, sandwiches, etc.). |

| Shelf Life | Paneer: Shorter shelf life, typically consumed fresh; Cheese: Longer shelf life, especially aged varieties. |

| Nutrition | Paneer: Higher in protein and fat, lower in sodium; Cheese: Varies by type, generally higher in sodium. |

| Melting | Paneer: Does not melt when heated; Cheese: Most varieties melt when heated. |

| Lactose | Paneer: Contains lactose; Cheese: Many aged cheeses have lower lactose content. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Origin and Source: Paneer is Indian, made from curdled milk; cheese is global, often aged, varied sources

- Production Process: Paneer uses acid coagulation; cheese involves rennet, bacteria, and aging techniques

- Texture and Taste: Paneer is soft, mild; cheese ranges from creamy to hard, tangy to sharp

- Culinary Uses: Paneer in curries, snacks; cheese in sandwiches, pasta, pizzas, and more

- Nutritional Differences: Paneer is higher in protein; cheese varies in fat, sodium, and calories

Origin and Source: Paneer is Indian, made from curdled milk; cheese is global, often aged, varied sources

Paneer, a staple in Indian cuisine, is crafted through a simple process of curdling milk with an acidic agent like lemon juice or vinegar. This method, rooted in centuries-old traditions, yields a fresh, unsalted cheese that is soft yet crumbly. Unlike many global cheeses, paneer is not aged, making it a quick and accessible ingredient for daily cooking. Its origins are deeply tied to the Indian subcontinent, where it has been a dietary cornerstone for vegetarians and a versatile component in dishes like palak paneer and paneer tikka.

Cheese, on the other hand, is a global phenomenon with a history spanning millennia and cultures. From the creamy Brie of France to the sharp Cheddar of England, cheese is as diverse as the regions it hails from. The process of making cheese often involves aging, which imparts complex flavors and textures. Whether it’s the blue veins of Roquefort or the smoky notes of Gouda, each variety reflects its source—be it cow, goat, or sheep milk—and the unique techniques of its makers. This diversity contrasts sharply with paneer’s singular, unaged profile.

To illustrate the difference, consider the production scale and purpose. Paneer is typically made in small batches, often at home, using minimal ingredients. Its simplicity aligns with its role as a protein-rich, everyday food. Cheese, however, is frequently produced industrially, with aging processes that can last from weeks to years. For instance, Parmigiano-Reggiano requires a minimum of 12 months to develop its signature hardness and umami flavor. This contrast highlights how paneer’s immediacy and cheese’s complexity cater to different culinary needs.

Practical tip: If you’re substituting paneer for cheese in a recipe, remember that paneer doesn’t melt like aged cheeses. Instead, it holds its shape, making it ideal for grilling or frying. For a paneer-like experience with a cheesy twist, try blending crumbled paneer with a small amount of melted mozzarella for dishes like stuffed peppers or casseroles. This hybrid approach bridges the gap between the two dairy products, offering the best of both worlds.

In essence, while paneer and cheese share a dairy base, their origins, production methods, and culinary roles diverge significantly. Paneer’s Indian heritage and fresh, unaged nature make it a distinct ingredient, whereas cheese’s global variety and aging processes create a vast, flavorful spectrum. Understanding these differences not only enriches your culinary knowledge but also empowers you to use each ingredient to its fullest potential.

Do Chicken Sandwiches Have Cheese? Exploring the Classic Debate

You may want to see also

Production Process: Paneer uses acid coagulation; cheese involves rennet, bacteria, and aging techniques

Paneer and cheese, though both dairy products, diverge significantly in their production processes, which fundamentally alter their textures, flavors, and uses. Paneer relies on acid coagulation, a straightforward method where an acid—such as lemon juice, vinegar, or citric acid (typically 1-2% of the milk volume)—is added to hot milk to separate curds from whey. This process takes minutes, yielding a fresh, unsalted product with a crumbly yet firm texture. In contrast, cheese production is a complex art involving rennet, bacteria, and aging. Rennet, an enzyme complex, coagulates milk more slowly (often 30-60 minutes), while bacteria cultures develop flavor and acidity. Aging, ranging from weeks to years, further transforms texture and taste, creating varieties from soft Brie to hard Parmesan.

Consider the steps involved in making paneer as a quick, accessible kitchen task. Heat whole milk to 80-90°C (176-194°F), add the acid gradually while stirring, and watch as curds form within minutes. Strain the mixture through cheesecloth, press gently to remove whey, and refrigerate for a few hours to set. This simplicity makes paneer a staple in Indian cuisine, ideal for dishes like palak paneer or paneer tikka. Cheese, however, demands precision and patience. After inoculating milk with bacteria cultures and rennet, the curd is cut, stirred, and heated to release moisture. Aging introduces molds, brine baths, or smoking, each step tailored to the desired variety. For instance, cheddar undergoes cheddaring—a process of stacking and cutting curds—before aging for 3-24 months, while mozzarella is stretched and kneaded for its signature elasticity.

The choice of coagulation method—acid versus rennet—dictates not only the production timeline but also the nutritional profile and culinary applications. Paneer’s acid-set curds retain more moisture and have a milder, milky flavor, making it a versatile ingredient for vegetarian dishes. Cheese, with its bacterial fermentation and aging, develops complex flavors—nutty, sharp, or earthy—and often has a lower lactose content due to bacterial activity. For example, aged cheddar contains negligible lactose, while paneer retains all its milk sugar. This distinction is crucial for dietary considerations, such as lactose intolerance.

From a practical standpoint, understanding these processes empowers home cooks to experiment. Want a quick, fresh cheese for salads or curries? Paneer’s acid coagulation is your go-to. Aiming for a mature, flavorful cheese to elevate a charcuterie board? Embrace the rennet, bacteria, and aging techniques of traditional cheesemaking. For instance, adding a pinch of lipase powder (0.05-0.1% of milk weight) during cheese production can introduce a sharp, tangy flavor reminiscent of aged pecorino. Meanwhile, adjusting acid levels in paneer—using less lemon juice for a softer texture—can tailor it for specific recipes.

In essence, while paneer and cheese share a dairy base, their production processes highlight a spectrum of possibilities. Paneer’s acid coagulation offers immediacy and simplicity, while cheese’s reliance on rennet, bacteria, and aging unlocks depth and diversity. Whether you’re a novice cook or a culinary enthusiast, mastering these techniques opens doors to creating dairy delights tailored to your palate and purpose.

Perfect Raclette Portions: Grams in a Cheese Slice Revealed

You may want to see also

Texture and Taste: Paneer is soft, mild; cheese ranges from creamy to hard, tangy to sharp

Paneer's texture is uniformly soft and crumbly, a consistency achieved through its simple production process: curdling milk with an acid like lemon juice or vinegar, then straining and pressing the curds. This minimal manipulation preserves its delicate structure, making it ideal for dishes where it needs to hold its shape without becoming rubbery—think cubes in a buttery curry or crumbled over a salad. Cheese, however, undergoes a more complex transformation. From the creamy spreadability of Brie to the crystalline hardness of aged Parmesan, its texture is dictated by factors like aging time, bacterial cultures, and moisture content. For instance, a young Cheddar is semi-soft and pliable, while a year-old Gouda develops a flaky, almost crunchy interior. This diversity means cheese can be melted, grated, sliced, or spread, adapting to a far wider range of culinary applications than paneer.

Taste-wise, paneer is a blank canvas. Its mild, milky flavor comes from its unsalted, unaged nature, allowing it to absorb spices and marinades without competing for dominance. This makes it a staple in Indian dishes like *palak paneer* or *shahi paneer*, where it soaks up the richness of cream, tomatoes, and garam masala. Cheese, in contrast, is a flavor powerhouse. The tanginess of a young goat cheese, the nuttiness of Gruyère, or the pungency of blue cheese all stem from bacterial cultures, aging, and regional production methods. For example, the sharp bite of a 2-year-old Cheddar comes from extended aging, while the smoky notes in a Gouda are often imparted during the smoking process. This complexity allows cheese to stand alone—on a charcuterie board or as a garnish—or to elevate dishes like a grilled cheese sandwich or a baked casserole.

To illustrate the practical differences, consider a recipe like stuffed bell peppers. Paneer’s softness and mildness make it an excellent filling when mixed with spices and herbs, as it binds well without overpowering the dish. Cheese, however, demands careful selection: a melted mozzarella would add gooey texture, while a sharp Cheddar would introduce a bold flavor contrast. For those experimenting with substitutions, remember that paneer won’t melt like cheese due to its low moisture and acid-set curds. Instead, it softens slightly, retaining its shape—a feature to leverage in dishes like paneer tikka skewers. Conversely, if a recipe calls for cheese and you’re out, a soft, mild cheese like fresh mozzarella or ricotta might mimic paneer’s texture, but the flavor profile will differ significantly.

For home cooks, understanding these differences can refine ingredient choices. If you’re making a vegetarian lasagna and want a mild, protein-rich layer, paneer can replace ricotta with the addition of salt and herbs to enhance its flavor. However, if you’re seeking a stretchy, melted layer, opt for a mozzarella or provolone. Similarly, in a salad, paneer’s crumbly texture pairs well with crisp vegetables, while a semi-soft cheese like goat cheese adds a tangy contrast. The key is to match the texture and taste to the dish’s requirements: paneer for subtlety and structure, cheese for diversity and boldness. This awareness not only prevents culinary mishaps but also opens doors to creative adaptations.

Finally, storage and handling highlight their distinctions. Paneer’s high moisture content means it spoils quickly—it should be consumed within 2–3 days of opening or stored in brine for up to a week. Cheese, especially hard varieties, can last months when properly wrapped and refrigerated. For instance, a block of Parmesan can be grated as needed, while paneer must be used promptly or frozen (though freezing alters its texture, making it firmer). This makes paneer a fresh, perishable ingredient best bought or made close to use, while cheese’s longevity allows for experimentation and exploration of its vast flavor spectrum. Whether you’re a novice or a seasoned cook, recognizing these nuances ensures both ingredients are used to their fullest potential.

Finding Nacho Cheese: A Guide to Grocery Store Locations

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Culinary Uses: Paneer in curries, snacks; cheese in sandwiches, pasta, pizzas, and more

Paneer and cheese, though both dairy products, serve distinct roles in global cuisines. Paneer, a fresh, unsalted cheese common in South Asian cooking, is a chameleon in curries, absorbing rich sauces without melting. Its firm texture makes it ideal for snacks like paneer tikka, where it’s marinated in yogurt and spices, then grilled to smoky perfection. Cheese, on the other hand, is a broad category with varieties like mozzarella, cheddar, and feta, each tailored to specific dishes. In sandwiches, melted cheddar adds gooey richness, while feta crumbles bring tangy contrast to salads. This fundamental difference in texture and flavor profile dictates their culinary applications.

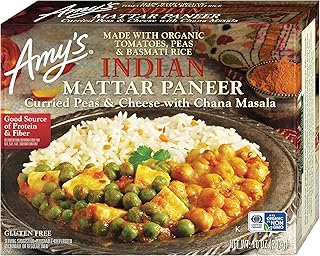

Consider the science behind their behavior in heat. Paneer’s low moisture content allows it to retain shape when simmered in curries like palak paneer or mattar paneer, making it a protein-rich centerpiece. Cheese, however, melts due to its higher fat and moisture levels, which is why mozzarella stretches on pizzas or gruyère forms a crispy crust on gratins. For home cooks, this means paneer is best added toward the end of cooking to avoid toughness, while cheese should be incorporated early to allow melting and integration. Experimenting with paneer in Western dishes like lasagna or cheese in Indian snacks like paneer-style kebabs can yield innovative fusion results.

Snacks highlight another divergence. Paneer’s mild taste and crumbly texture shine in dishes like paneer pakora, where it’s battered and fried, or in chaat, where it’s tossed with spices and chutneys. Cheese, meanwhile, stars in handheld bites like grilled cheese sandwiches or cheese-stuffed jalapeño poppers, where its meltability is key. For health-conscious cooks, paneer’s lower lactose content compared to aged cheeses makes it a gentler option for lactose-intolerant individuals. Pairing paneer with mint chutney or cheese with apple slices offers balanced flavor and texture combinations.

In pasta and pizza, cheese’s versatility is unmatched. Parmesan adds umami to carbonara, while mozzarella’s stretchiness is essential for margherita pizza. Paneer, though less conventional, can be grated and sprinkled over pasta for a nutty twist or cubed and baked on flatbreads for a desi-style pizza. The key is understanding their melting points: paneer won’t melt like mozzarella but will brown slightly, adding a unique texture. For best results, use paneer in dishes where structural integrity is desired, and cheese where creaminess or stretch is the goal.

Ultimately, while paneer and cheese share dairy origins, their culinary uses are worlds apart. Paneer’s role in curries and snacks hinges on its ability to hold shape and absorb flavors, making it a staple in vegetarian Indian cuisine. Cheese’s melting properties and flavor diversity dominate Western dishes like sandwiches, pasta, and pizzas. By recognizing these differences, cooks can confidently substitute or innovate, whether crafting a paneer-stuffed grilled cheese or a cheddar-infused curry. Both ingredients, when used thoughtfully, elevate dishes to new heights.

Bee Wax Cheese Wraps in England: Availability and Eco-Friendly Options

You may want to see also

Nutritional Differences: Paneer is higher in protein; cheese varies in fat, sodium, and calories

Paneer, a staple in South Asian cuisine, and cheese, a global dairy favorite, often spark comparisons, but their nutritional profiles diverge significantly. While both are dairy products, paneer stands out for its higher protein content, making it a preferred choice for those aiming to boost their protein intake. A 100-gram serving of paneer provides approximately 18–20 grams of protein, compared to 7–10 grams in most cheeses like cheddar or mozzarella. This difference is largely due to paneer’s production process, which involves curdling milk with acid and retaining more of the milk’s protein solids.

Cheese, on the other hand, is a more diverse category, with variations in fat, sodium, and calorie content depending on the type. For instance, a 100-gram serving of feta cheese contains around 21 grams of fat and 490 mg of sodium, while the same amount of cottage cheese has only 4 grams of fat and 360 mg of sodium. Paneer, in contrast, typically contains 20–25 grams of fat per 100 grams, with sodium levels around 250–300 mg, making it a more consistent option for those monitoring fat and sodium intake. However, its calorie density (around 260–300 calories per 100 grams) is comparable to many cheeses, so portion control remains key.

For individuals with specific dietary goals, understanding these differences is crucial. Athletes or those in muscle-building phases may favor paneer for its superior protein content, while individuals on low-sodium diets might opt for softer, fresher cheeses like ricotta or paneer over aged, harder varieties. Similarly, those aiming to reduce fat intake could choose part-skim mozzarella or cottage cheese over paneer or high-fat cheeses like brie. Pairing paneer with fiber-rich vegetables or whole grains can also balance its higher fat content, making it a more nutritious meal option.

Practical tips for incorporating these dairy products into a balanced diet include using paneer as a protein-rich addition to salads or curries, while reserving cheese for flavor enhancement in smaller quantities. For example, swapping a 30-gram serving of cheddar (120 calories, 9 grams of fat) for the same amount of paneer (87 calories, 7 grams of fat) in a sandwich reduces overall fat and calorie intake while increasing protein. Additionally, homemade paneer allows for control over salt and fat content, offering a healthier alternative to store-bought varieties.

In summary, while paneer and cheese share dairy origins, their nutritional differences make them suited to distinct dietary needs. Paneer’s higher protein content and moderate sodium levels cater to protein-focused diets, whereas cheese’s variability in fat, sodium, and calories requires careful selection based on individual health goals. By understanding these nuances, one can make informed choices to optimize nutrition without sacrificing flavor.

Is Subway's Chipotle Southwest Steak and Cheese Wrap Spicy?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, paneer and cheese are not the same. Paneer is a type of fresh, unsalted cheese commonly used in South Asian cuisine, while cheese is a broader category of dairy products that include various types like cheddar, mozzarella, and feta.

Paneer can sometimes be used as a substitute for cheese, especially in dishes where a mild, crumbly texture is desired. However, it lacks the meltability and flavor profile of most cheeses, so it may not work in all recipes.

Paneer is made by curdling milk with an acid like lemon juice or vinegar, then straining and pressing the curds. While this process is similar to cheese-making, paneer is not aged or cultured like many other cheeses.

Paneer has a mild, milky flavor and a firm, crumbly texture, which is different from most aged or flavored cheeses. It is less tangy and does not melt like traditional cheese.

Paneer and cheese both contain protein, fat, and calcium, but their nutritional profiles can vary. Paneer is typically higher in protein and lower in salt compared to aged cheeses, but it may have a higher fat content depending on the milk used.