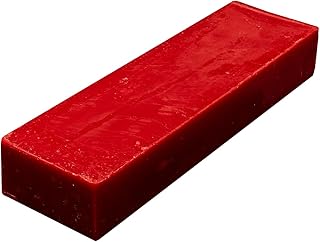

The question of whether wax on cheese is edible often arises among cheese enthusiasts and casual consumers alike. Cheese wax, typically used to preserve and protect the cheese during aging, serves as a barrier against mold and moisture loss. While it is generally not intended for consumption, many types of cheese wax are made from food-grade materials and are technically safe to eat, though not particularly palatable. However, it’s advisable to remove the wax before eating, as it can be difficult to digest and may detract from the cheese’s flavor and texture. Understanding the purpose and composition of cheese wax helps clarify its role in cheese preservation and whether it poses any risks if accidentally ingested.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Edibility | Generally not recommended for consumption |

| Purpose | Protects cheese from mold and moisture loss during aging |

| Material | Typically made from paraffin or food-grade wax |

| Digestibility | Not easily digestible by humans |

| Safety | Non-toxic but may cause digestive discomfort if ingested |

| Removal | Should be removed before eating the cheese |

| Common Use | Found on cheeses like Gouda, Edam, and Cheddar |

| Alternative | Some natural waxes (e.g., beeswax) are edible but still not advised for consumption |

| Regulatory | Food safety authorities advise against eating wax coatings |

| Texture | Hard and inedible, often chewy or waxy |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Types of Cheese Wax

Cheese wax serves a dual purpose: preserving the cheese and protecting it from mold and contaminants. But not all waxes are created equal. The type of wax used can affect both the cheese's aging process and its safety for consumption. Here's a breakdown of common cheese wax varieties and their unique characteristics.

Paraffin Wax: The most common and affordable option, paraffin wax is derived from petroleum. It creates a strong barrier against moisture loss and mold, making it ideal for long-term aging. However, paraffin is not edible and must be removed before consuming the cheese.

Beeswax: A natural alternative, beeswax is prized for its breathability, allowing the cheese to mature while still providing protection. Its slightly sweet aroma can subtly influence the cheese's flavor. While technically edible, consuming large amounts of beeswax is not recommended.

Microcrystalline Wax: This wax, a derivative of petroleum, offers superior flexibility and adhesion compared to paraffin. It's often blended with other waxes to improve their performance. Like paraffin, microcrystalline wax is not intended for consumption.

Carnauba Wax: Derived from palm leaves, carnauba wax is the hardest natural wax available. It provides excellent moisture resistance but can be brittle. Carnauba wax is generally considered safe for consumption in small quantities.

Soy Wax: A plant-based option, soy wax is gaining popularity due to its sustainability and biodegradability. It offers good moisture resistance but may not be as durable as paraffin or microcrystalline wax. Soy wax is generally regarded as safe for consumption.

When choosing a cheese wax, consider the desired aging time, the type of cheese, and your personal preferences regarding natural vs. synthetic materials. Remember, always remove wax before eating cheese, unless specifically labeled as edible.

Perfect Toasted Ham and Cheese Hoagie: Easy Recipe Guide

You may want to see also

Safety of Consuming Wax

The wax coating on certain cheeses, such as Gouda or Edam, serves primarily as a protective barrier against moisture loss and mold growth during aging. While it is not intended for consumption, accidental ingestion of small amounts is generally considered safe. The wax used is typically food-grade, derived from sources like paraffin or carnauba, and does not contain toxic additives. However, its indigestible nature means it passes through the digestive system without being broken down, potentially causing mild discomfort if consumed in larger quantities.

From a safety perspective, the key concern is not toxicity but physical obstruction. Swallowing large pieces of wax could pose a choking hazard, particularly in children or individuals with swallowing difficulties. For this reason, it is advisable to remove the wax layer entirely before serving cheese, especially in households with young children or elderly individuals. If small amounts are inadvertently consumed, they are unlikely to cause harm but may result in temporary gastrointestinal symptoms like bloating or constipation.

To minimize risks, follow these practical steps: first, use a clean knife to carefully cut away the wax coating, ensuring no fragments remain on the cheese surface. Second, educate household members, especially children, about the non-edible nature of the wax to prevent accidental ingestion. Third, dispose of the wax properly, as it is not biodegradable and can harm the environment if discarded incorrectly. For those with sensitivities or concerns, opt for wax-free cheese varieties or those packaged in alternative protective materials.

Comparatively, the safety profile of cheese wax is more favorable than that of non-food-grade waxes, such as those used in candles or polishes, which may contain harmful chemicals. However, it is not a substitute for edible coatings like rind or brine. While the wax itself is inert, its presence can detract from the sensory experience of the cheese, masking flavors and textures. Thus, its removal enhances both safety and enjoyment, making it a simple yet essential step in cheese preparation.

In conclusion, while the wax on cheese is technically edible in small amounts, its consumption offers no nutritional benefit and carries minor risks. Treating it as a non-food component aligns with best practices for food safety and culinary enjoyment. By understanding its purpose and handling it appropriately, consumers can confidently savor their cheese without concern, ensuring a pleasant and hazard-free experience.

Is Cheese Gay? Debunking Stereotypes and Embracing Food Freedom

You may want to see also

Wax Removal Methods

The wax coating on cheese serves as a protective barrier, preserving its flavor and texture during aging and storage. While some claim it’s edible, most experts advise against consuming it due to potential additives and lack of palatability. For those who prefer to remove it before enjoying their cheese, several effective methods exist, each suited to different preferences and tools available.

Peeling by Hand: A Simple Approach

For softer wax coatings, manual removal is often the easiest method. Start by gently pinching a corner of the wax between your thumb and forefinger, then slowly peel it back like removing a sticker. Work carefully to avoid leaving residue on the cheese. This method is ideal for cheeses with thin, pliable wax layers, such as young Goudas or Cheddars. Avoid using sharp tools, as they can damage the cheese surface.

Heat Application: Precision Required

For thicker or more stubborn wax, applying heat can soften it for easier removal. Use a hairdryer on a low setting or hold the cheese near (but not touching) a warm oven. Heat the wax until it becomes pliable but not melted, then peel it away. Be cautious not to overheat, as excessive warmth can alter the cheese’s texture. This method is particularly useful for harder wax coatings on aged cheeses like Edam or Gouda.

Freezing Technique: A Less Common but Effective Option

An alternative approach involves freezing the cheese for 15–20 minutes to make the wax brittle. Once chilled, tap the wax gently with a spoon or butter knife to crack it into pieces, which can then be removed by hand. This method minimizes contact with the cheese itself, preserving its integrity. However, it’s best suited for smaller cheese portions, as larger blocks may not freeze uniformly.

Chemical Solvents: A Last Resort

In rare cases, stubborn wax residues may require the use of food-safe solvents like mineral oil or vinegar. Apply a small amount to a cloth and rub the affected area gently. While effective, this method should be used sparingly, as solvents can alter the cheese’s flavor. Always ensure the product is food-grade and rinse the cheese thoroughly afterward. This approach is typically reserved for professional settings or extreme cases.

Each wax removal method has its advantages and limitations, depending on the cheese type and wax thickness. Whether opting for manual peeling, heat application, freezing, or solvents, the goal remains the same: to enjoy the cheese without the wax barrier. By choosing the right technique, you can preserve both the flavor and presentation of your cheese.

Why Cheese Isn't Vegan: Understanding Dairy's Non-Vegan Origins

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Health Effects of Cheese Wax

Cheese wax, often used to preserve and protect cheese during aging, is a topic of curiosity for many cheese enthusiasts. While it serves a functional purpose, the question of its edibility and potential health effects lingers. The wax itself is typically made from food-grade paraffin or, in some cases, natural waxes like beeswax. These materials are generally considered safe for contact with food, but their consumption raises specific considerations.

From an analytical perspective, the primary health concern with cheese wax is its indigestibility. The human digestive system is not equipped to break down wax, meaning it will pass through the body without being absorbed. While this typically does not cause harm in small amounts, consuming large quantities could lead to gastrointestinal discomfort, such as bloating or constipation. For instance, accidentally ingesting a small piece of wax while eating cheese is unlikely to cause issues, but deliberately eating wax is not recommended.

Instructively, if you find yourself with wax-coated cheese, the best practice is to remove the wax before consumption. Use a knife or peeler to carefully separate the wax from the cheese, ensuring no small pieces remain. This is especially important for children or individuals with sensitive digestive systems, as they may be more susceptible to discomfort. Additionally, always check the type of wax used; natural waxes like beeswax are generally safer than synthetic alternatives, though neither is intended for consumption.

Persuasively, it’s worth noting that cheese wax is not a nutritional contributor. Unlike the cheese itself, which provides protein, calcium, and other essential nutrients, the wax offers no health benefits. Therefore, there is no reason to include it in your diet. Instead, focus on enjoying the cheese while treating the wax as a protective layer to be discarded. This approach ensures you maximize the nutritional value of your meal without unnecessary risks.

Comparatively, the health effects of cheese wax can be likened to those of other non-food items accidentally ingested, such as gum or fruit pits. While not toxic, these items serve no purpose in the diet and can cause discomfort if consumed in excess. Just as you would avoid swallowing gum, treat cheese wax as a non-edible component of your food. This mindset simplifies decision-making and promotes safer eating habits.

In conclusion, while cheese wax is not toxic, it is not intended for consumption and offers no health benefits. Its indigestible nature makes it a potential source of discomfort if ingested, particularly in large amounts. By removing the wax before eating cheese and understanding its role as a protective barrier, you can enjoy your cheese safely and without concern. Always prioritize the edible portion of your food and treat non-food components like wax with caution.

String Cheese and Potassium: Unraveling the Nutritional Facts

You may want to see also

Alternatives to Wax Coating

Wax coatings on cheese serve a practical purpose—preserving moisture and protecting against mold—but their edibility remains a point of confusion for consumers. While food-grade wax is technically safe to eat, many find it unpalatable and prefer to remove it. This has spurred innovation in alternative coatings that balance preservation with consumer preferences. Below are several viable options, each with unique advantages and considerations.

Natural Biofilms: A Biodegradable Solution

Derived from sources like alginate, carrageenan, or microbial fermentation, natural biofilms form a thin, edible barrier that mimics wax’s protective qualities. For instance, a 2022 study found that alginate-based coatings extended the shelf life of cheddar by up to 21 days while remaining imperceptible to taste. To apply, dissolve 2 grams of sodium alginate in 100ml of water, dip the cheese, and let it air-dry for 10 minutes. While slightly more expensive than wax, biofilms appeal to eco-conscious consumers due to their compostability.

Fat-Based Coatings: Traditional Meets Modern

Butterfat or lard coatings were historically used before wax became standard. Modern iterations involve blending these fats with antimicrobial agents like nisin to enhance preservation. A 2021 trial showed butterfat coatings reduced mold growth by 70% on soft cheeses. However, this method is best suited for short-term storage (up to 3 weeks) and refrigerated conditions, as fats can spoil in warmer temperatures. Apply by brushing a thin layer onto the cheese surface and chilling for 30 minutes.

Edible Plant-Based Waxes: A Middle Ground

For those hesitant to abandon wax entirely, plant-based alternatives like carnauba or candelilla wax offer a familiar solution. These waxes are harder and less likely to be mistaken for cheese, encouraging removal. A 2020 survey revealed 85% of consumers preferred carnauba wax over petroleum-based options due to its natural origin. Melt the wax at 70°C, dip the cheese, and cool for 5 minutes. While not biodegradable, these waxes are non-toxic and suitable for vegan products.

Vacuum Sealing and Modified Atmosphere Packaging (MAP): Wax-Free Innovations

For industrial-scale solutions, vacuum sealing or MAP eliminates the need for coatings altogether. MAP involves replacing air with a gas mixture (e.g., 40% carbon dioxide, 60% nitrogen) to inhibit bacterial growth. This method extends shelf life by up to 60 days but requires specialized equipment. Small-scale producers can opt for vacuum bags, though this may flatten softer cheeses. Pairing MAP with a light biofilm coating maximizes preservation without compromising texture.

Each alternative addresses specific pain points—whether sustainability, taste, or scalability. By understanding their strengths and limitations, producers and consumers can make informed choices that align with their priorities, moving beyond the wax debate toward more innovative solutions.

Amanda the Adventurer's Cheese Mystery: Uncovering the Hidden Dairy Delight

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The wax on cheese is generally not intended to be eaten, though it is typically made from food-grade materials and is non-toxic.

Wax is used to create a protective barrier that helps preserve the cheese by preventing moisture loss and inhibiting mold growth during aging and storage.

While cheese wax is non-toxic, it is not digestible and can cause discomfort if consumed in large amounts. It’s best to remove and discard the wax before eating the cheese.

Cheese wax is usually made from paraffin, microcrystalline wax, or a blend of both, often with added food-grade colorings to make it visually appealing.

![Fit Meal Prep [250 Sheets] 12x12" Deli Paper Sheets, Green and White Checkered Dry Waxed Paper, Sandwich Wrapping, Grease-Proof Wax Paper for Food Basket, Chritmas Parties, Picnic, Burgers](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/71pTmgrWkUL._AC_UL320_.jpg)