Aged cheese turning green is a fascinating phenomenon that often sparks curiosity among cheese enthusiasts and casual consumers alike. This unusual discoloration typically occurs due to the growth of harmless mold species, such as *Penicillium* or *Scopulariopsis*, which thrive in the humid, nutrient-rich environment of aging cheese. While green mold can be off-putting, it is not always a sign of spoilage; in fact, some artisanal cheeses, like certain varieties of blue cheese, intentionally cultivate these molds as part of their flavor profile. However, in other cases, green mold may indicate improper storage or contamination, making it essential to understand the context and type of cheese before consuming it.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Mold Types: Penicillium candidum or Penicillium camemberti cause green hues in aged cheeses

- Aging Conditions: High humidity and specific temperatures promote green mold growth

- Cheese Varieties: Brie, Camembert, and other soft-ripened cheeses often develop green exteriors

- Safety Concerns: Green mold is typically safe but inspect for harmful varieties before consuming

- Flavor Impact: Green mold adds earthy, nutty flavors, enhancing the cheese's complexity

Mold Types: Penicillium candidum or Penicillium camemberti cause green hues in aged cheeses

The green hues in aged cheeses often spark curiosity, but not all molds are created equal. Among the culprits behind this phenomenon are *Penicillium candidum* and *Penicillium camemberti*, two molds intentionally introduced during the aging process of specific cheeses. These molds are not only safe but also essential for developing the characteristic flavors and textures of cheeses like Camembert and Brie. Their green spores, though less common than their white counterparts, can appear under certain conditions, such as higher humidity or specific aging environments. Understanding these molds helps demystify why some cheeses take on a greenish tint, turning what might seem like a flaw into a mark of craftsmanship.

To cultivate these molds effectively, cheesemakers follow precise steps. *Penicillium candidum* and *Penicillium camemberti* are typically applied as a powder or spray to the cheese’s surface during the first stages of aging. The ideal temperature for their growth ranges between 50°F and 55°F (10°C–13°C), with humidity levels around 90–95%. Over 2–4 weeks, the molds form a velvety rind, and under specific conditions, their green spores may emerge. For home cheesemakers, maintaining consistent humidity is key—use a cheese aging box with a water reservoir to control moisture levels. Avoid overhandling the cheese during this phase, as it can disrupt mold growth and lead to uneven coloration.

While *Penicillium candidum* and *Penicillium camemberti* are generally safe, their green hues can sometimes be mistaken for harmful molds. To distinguish between them, inspect the cheese’s texture and smell. Beneficial molds produce a soft, bloomy rind with a mild, earthy aroma, while harmful molds often appear fuzzy, multicolored, or emit an ammonia-like odor. If in doubt, discard the cheese. For those with mold allergies, even safe molds can trigger reactions, so moderation is advised. Always store aged cheeses properly—wrap them in wax or parchment paper, not plastic, to allow them to breathe without drying out.

Comparing *Penicillium candidum* and *Penicillium camemberti* reveals subtle differences in their impact on cheese. *Penicillium camemberti* is more commonly used in Camembert, producing a slightly firmer rind and a sharper flavor profile. *Penicillium candidum*, on the other hand, is favored for Brie, resulting in a softer rind and a milder, buttery taste. The green spores of both molds are more likely to appear in artisanal or small-batch cheeses, where aging conditions are less standardized. This variation adds to the uniqueness of each wheel, making green hues a sign of individuality rather than imperfection.

In conclusion, the green tones caused by *Penicillium candidum* and *Penicillium camemberti* are not defects but indicators of a cheese’s artisanal nature. By understanding these molds and their role in the aging process, cheese enthusiasts can appreciate the complexity behind their favorite aged varieties. Whether you’re a cheesemaker or a connoisseur, recognizing these green hues as a natural part of the aging process enhances your enjoyment and knowledge of this timeless craft. Embrace the green—it’s a testament to the art of cheese.

Is a Cheese Sandwich Vegetarian? Exploring Ingredients and Dietary Concerns

You may want to see also

Aging Conditions: High humidity and specific temperatures promote green mold growth

Green mold on aged cheese isn't random. It thrives under specific, controllable conditions. High humidity, typically above 85%, creates a moisture-rich environment where mold spores can germinate and spread. Combine this with temperatures between 50°F and 60°F (10°C–15°C), and you’ve got the ideal incubator for Penicillium candidum or other green mold species. These conditions mimic the natural caves where cheeses like Roquefort or Stilton were historically aged, but modern cheesemakers must carefully monitor these factors to balance flavor development and mold growth.

To achieve this balance, consider the aging environment’s design. Use humidity-controlled chambers or cellars with consistent airflow to prevent stagnant moisture pockets. Hygrometers and thermometers are essential tools—calibrate them regularly to ensure accuracy. For home cheesemakers, a wine fridge modified with a humidity tray (filled with water or damp sponges) can replicate these conditions. However, avoid overshooting humidity levels, as this can lead to excessive mold growth or unwanted bacterial activity.

Not all green molds are created equal. Penicillium camemberti, for instance, is desirable on Camembert, while others may indicate spoilage. The key is intentionality. If green mold is part of the cheese’s profile, maintain the aging conditions rigorously. If not, adjust humidity downward to 75–80% or raise temperatures slightly to discourage mold growth. Regularly inspect the cheese, removing any unwanted mold with a sterile tool and ensuring the rind remains intact.

Aging cheese is as much art as science. High humidity and specific temperatures are tools, not rules. Experiment with slight variations—a degree cooler, a percentage drier—to observe how these changes affect mold development and flavor. Document your findings to refine your process. Remember, green mold can be a feature, not a flaw, when controlled with precision and purpose.

Unraveling the Mystery of Department 1-R in 'I Am the Cheese

You may want to see also

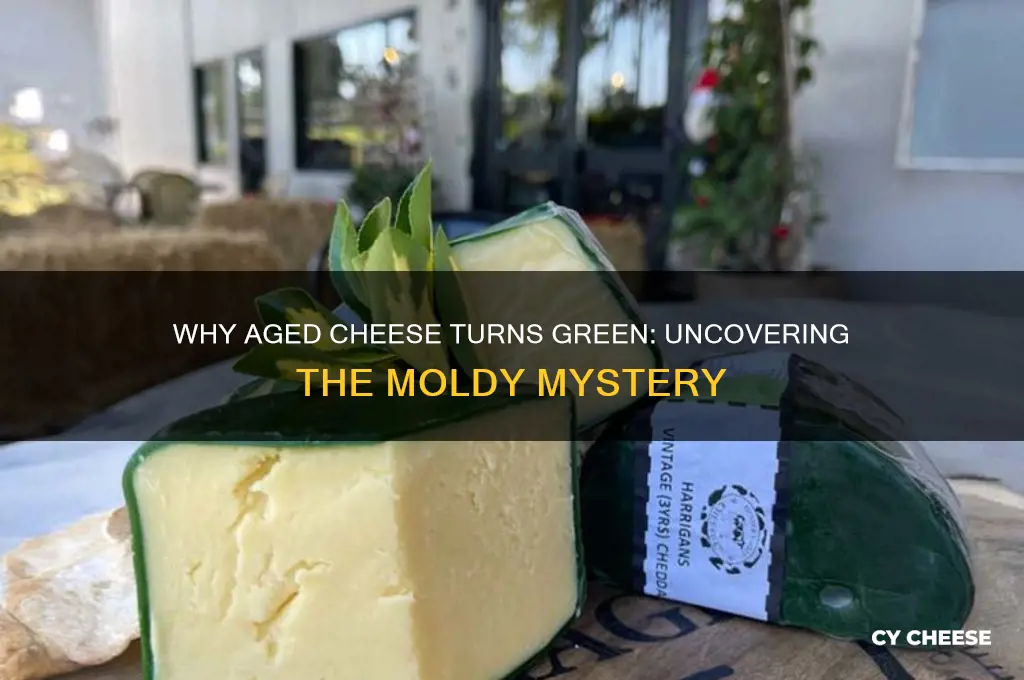

Cheese Varieties: Brie, Camembert, and other soft-ripened cheeses often develop green exteriors

Soft-ripened cheeses like Brie and Camembert are celebrated for their creamy interiors and bloomy rinds, but their green exteriors often raise eyebrows. This phenomenon is primarily due to the growth of *Penicillium* molds, which are intentionally introduced during production. While white *Penicillium camemberti* dominates the rind, green patches emerge when *P. candidum* or rogue molds like *Byssochlamys* or *Scopulariopsis* take hold. These green molds thrive in high-moisture environments, particularly when cheeses are aged beyond 3–4 weeks or stored improperly. For instance, Camembert stored at 12°C (54°F) with 90% humidity is more prone to greening than Brie aged at cooler temperatures.

To prevent greening, home cheesemakers and enthusiasts should monitor humidity levels, ideally keeping them below 85%. Wrapping cheeses in wax paper instead of plastic allows moisture to escape, reducing mold proliferation. If green spots appear, assess their texture: fuzzy or powdery growths are typically benign, while slimy patches indicate spoilage. In commercial settings, producers often treat rinds with diluted acetic acid (1–2%) to inhibit unwanted molds without compromising flavor. However, this method requires precision, as overuse can alter the cheese’s pH and taste profile.

Comparatively, green rinds on soft-ripened cheeses differ from those on aged hard cheeses like Stilton, where blue-green veins are part of the design. In Brie and Camembert, greening is usually a sign of overripeness or contamination, not a desirable trait. While some artisanal producers embrace these imperfections as markers of natural aging, most consumers prefer the classic white rind. For those experimenting with aging, keep detailed logs of temperature, humidity, and visual changes to identify patterns that lead to greening.

Persuasively, embracing green rinds as a natural part of the aging process can deepen appreciation for artisanal cheese. However, safety should always come first. If the green mold emits an ammonia-like odor or the cheese feels excessively soft, discard it. For the adventurous, small green patches can be trimmed, allowing the rest of the cheese to be enjoyed. Ultimately, understanding the science behind greening empowers both makers and consumers to navigate this quirky aspect of soft-ripened cheeses with confidence.

Is Munster a Processed Cheese? Unraveling the Truth Behind This Classic

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Safety Concerns: Green mold is typically safe but inspect for harmful varieties before consuming

Green mold on aged cheese often raises alarms, but not all varieties are cause for concern. Many aged cheeses, like Roquefort or Stilton, intentionally cultivate Penicillium molds to achieve their distinctive flavors and textures. These molds are generally safe and even contribute to the cheese’s character. However, the presence of green mold on cheeses not meant to have it warrants scrutiny. Understanding the difference between benign and harmful molds is crucial to ensure safety.

Inspecting green mold requires a keen eye and a bit of knowledge. Harmful molds, such as those from the Aspergillus or Fusarium families, can produce toxins like aflatoxins, which are dangerous even in small amounts. Look for signs of contamination: if the mold is fuzzy, brightly colored (e.g., vibrant green or yellow), or spreads beyond the surface, discard the cheese. Hard cheeses like Parmesan can be salvaged by cutting away the moldy part plus an inch of surrounding cheese, but soft cheeses should be discarded entirely due to the risk of toxin penetration.

Children, pregnant individuals, and those with compromised immune systems should avoid moldy cheese altogether, as they are more susceptible to foodborne illnesses. For others, moderation is key. While occasional exposure to benign molds is unlikely to cause harm, repeated consumption of questionable cheese increases risk. Always store cheese properly—wrapped in wax or parchment paper, not plastic, which traps moisture and encourages mold growth. Refrigeration below 40°F (4°C) slows mold development but doesn’t eliminate it entirely.

Practical tips can help minimize risk. If you’re unsure about the mold type, err on the side of caution and discard the cheese. For cheeses meant to have green mold, purchase from reputable sources that adhere to safety standards. Homemade aging projects should follow strict hygiene protocols, including using food-grade molds and monitoring humidity levels. While green mold on aged cheese isn’t always a red flag, informed inspection and cautious handling are essential to enjoying it safely.

Understanding the Volume of 8 Ounces of Cheese: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Flavor Impact: Green mold adds earthy, nutty flavors, enhancing the cheese's complexity

Green mold on aged cheese isn't a defect—it's a deliberate choice that transforms flavor. Penicillium candidum, the mold responsible for the green veins in cheeses like Camembert and Brie, also contributes to their earthy, mushroom-like notes. When this mold is allowed to develop on the surface of harder cheeses like Saint-Marcellin or Reblochon, it introduces a nutty, almost grassy complexity that contrasts with the richer, buttery interior. This interplay of flavors is a hallmark of artisanal cheesemaking, where mold isn't an accident but an ingredient.

To achieve this flavor profile, cheesemakers carefully control humidity and temperature during aging. The mold thrives in environments with 90-95% humidity and temperatures around 50-55°F (10-13°C). Too dry, and the mold won’t develop; too warm, and it becomes bitter. The green mold’s growth is typically limited to the first 2-3 weeks of aging, after which the cheese is brushed or washed to prevent overgrowth. This balance ensures the mold enhances, rather than overwhelms, the cheese’s natural flavors.

The earthy and nutty notes from green mold pair exceptionally well with specific foods and beverages. For instance, a green-molded cheese like Saint-Marcellin, aged 4-6 weeks, complements a crisp white wine like Sauvignon Blanc or a light, fruity beer. When serving, allow the cheese to come to room temperature to fully express its complex flavors. Pair it with honey, nuts, or crusty bread to highlight the mold’s contribution. Avoid overpowering condiments like strong mustards or jams, which can mask the delicate nuances.

While green mold is safe and desirable in certain cheeses, not all green molds are created equal. Cheesemakers must distinguish between beneficial molds like Penicillium candidum and harmful ones like Aspergillus. If you’re experimenting with aging cheese at home, start with small batches and monitor closely. Use a clean, dedicated aging space and regularly inspect for off-odors or colors. When in doubt, consult a professional or discard the cheese—safety always comes first.

The takeaway? Green mold isn’t just a visual marker of aged cheese; it’s a flavor enhancer that adds depth and complexity. By understanding its role and controlling its growth, cheesemakers—and home enthusiasts—can craft cheeses that are both unique and delicious. Embrace the green, but do so with knowledge and care.

Blueberries and Cheese: Unexpected Pairings for a Sweet and Savory Delight

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Aged cheese can turn green due to the growth of harmless mold species, such as *Penicillium* or *Scopulariopsis*, which produce green spores or pigments as they colonize the cheese surface.

Green mold on aged cheese is generally safe to eat if the cheese is a variety that naturally develops mold as part of its aging process, like blue cheese. However, if the mold is unexpected or the cheese smells off, it’s best to discard it.

Yes, aged cheese can turn green due to other factors, such as the presence of copper or iron in the milk, which can react with air during aging to create a greenish hue, though this is less common than mold-related greening.