Cheese curds are a delightful and often underappreciated dairy product, beloved in certain regions for their unique texture and flavor. Essentially, they are the fresh, solid bits that form during the early stages of cheese production, before aging or pressing. Unlike aged cheeses, curds are soft, squeaky, and slightly rubbery, with a mild, milky taste. They are best enjoyed fresh, often served warm or at room temperature, and are a popular snack in places like Wisconsin and Quebec. Whether eaten on their own, battered and fried, or paired with gravy in the iconic dish poutine, cheese curds offer a simple yet satisfying culinary experience that highlights the pure essence of cheese in its most basic form.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Fresh, unsalted, and unaged cheese in its initial form before being processed into other types of cheese. |

| Texture | Squeaky, moist, and slightly rubbery when fresh; can become softer as it ages. |

| Flavor | Mild, milky, and slightly tangy; flavor can vary based on the milk used (cow, goat, sheep). |

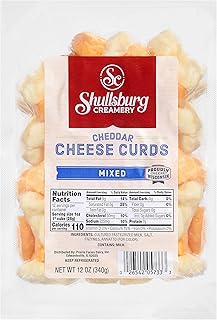

| Appearance | Small, irregular chunks or balls, often white or pale yellow in color. |

| Origin | Commonly associated with Wisconsin, USA, but produced in other regions as well. |

| Production | Made by curdling milk with rennet or acid, then separating the curds from the whey. |

| Shelf Life | Best consumed fresh within a few days; can last up to a week when refrigerated. |

| Uses | Eaten as a snack, breaded and fried (e.g., cheese curds in poutine), or used in recipes. |

| Regional Names | Squeaky cheese, breakfast cheese, or simply curds in different regions. |

| Pairings | Often served with ketchup, ranch dressing, or as part of dishes like poutine or salads. |

Explore related products

$34.95

What You'll Learn

- Definition: Cheese curds are fresh, unsalted milk solids formed during cheese-making before aging or pressing

- Texture: Known for squeaky, springy texture due to retained moisture and loose protein structure

- Production: Made by curdling milk with rennet or acid, then cutting and heating the curds

- Serving: Often eaten plain, fried, or paired with dishes like poutine or salads

- Regional Popularity: Especially popular in Wisconsin, Canada, and parts of the Midwest

Definition: Cheese curds are fresh, unsalted milk solids formed during cheese-making before aging or pressing

Cheese curds are the unsung heroes of the cheese-making process, often overshadowed by their aged and pressed counterparts. These fresh, unsalted milk solids are the foundation of all cheese, yet they stand alone as a delicacy in their own right. Formed during the early stages of cheese-making, curds are the result of coagulated milk, separated from the whey, and are a testament to the transformative power of simple ingredients. This definition highlights their purity and potential, offering a glimpse into the art and science of cheese production.

To understand cheese curds, imagine the moment milk transitions from liquid to solid. This occurs when rennet or acid is added, causing the milk proteins to bind together. The curds are then gently cut and stirred, releasing whey and forming small, soft masses. At this stage, they are at their most delicate and flavorful, retaining the natural sweetness of the milk. Unlike aged cheeses, which develop complex flavors and textures over time, cheese curds offer a pristine, unadulterated experience. Their freshness is their hallmark, making them a favorite in regions like Wisconsin and Quebec, where they are celebrated for their squeaky texture and mild taste.

From a culinary perspective, cheese curds are incredibly versatile. They can be eaten plain, battered and fried for a crispy treat, or incorporated into dishes like poutine. Their mild flavor pairs well with bold ingredients, while their texture adds a unique contrast. For those experimenting with cheese-making at home, producing curds is a rewarding first step. The process requires minimal equipment—a pot, thermometer, and rennet—and yields results in as little as an hour. However, achieving the perfect squeak or texture may take practice, as factors like milk temperature and acidity play critical roles.

Comparatively, cheese curds differ significantly from other cheese products. While aged cheeses undergo pressing, salting, and aging to develop their characteristic flavors, curds remain untouched, preserving their natural state. This makes them a healthier option, as they contain less salt and fewer additives. Additionally, their short shelf life encourages immediate consumption, aligning with trends toward fresh, minimally processed foods. For those seeking a pure, unaltered dairy experience, cheese curds are unparalleled.

In conclusion, cheese curds are more than just a byproduct of cheese-making—they are a celebration of freshness and simplicity. Their definition as unsalted milk solids formed before aging or pressing underscores their unique qualities. Whether enjoyed on their own or as part of a dish, they offer a direct connection to the origins of cheese. For enthusiasts and novices alike, exploring cheese curds provides a deeper appreciation for the craft of cheese-making and the beauty of unadorned ingredients.

Is Dairylea Real Cheese? Unraveling the Truth Behind the Popular Snack

You may want to see also

Texture: Known for squeaky, springy texture due to retained moisture and loose protein structure

Cheese curds, particularly those prized for their freshness, owe their iconic squeak to a delicate balance of moisture and protein structure. Unlike aged cheeses where moisture evaporates and proteins tighten, curds retain a higher water content, keeping the protein matrix loose and flexible. This flexibility allows the proteins to rub against each other when you bite into a curd, creating the distinctive squeaky sound that’s a hallmark of freshness. Think of it as the difference between a dry, brittle rubber band and a hydrated, stretchy one—moisture is the key to elasticity.

To experience this texture at its peak, aim to consume cheese curds within 24 hours of production. After this window, moisture begins to evaporate, and the protein structure tightens, diminishing the squeak. If you’re purchasing curds, look for packaging dates and prioritize those made locally to ensure minimal transit time. For optimal squeakiness, serve curds at room temperature; cold curds can feel firmer and less springy due to reduced protein mobility.

If you’re making cheese curds at home, control over moisture is critical. During the curdling process, avoid over-stirring or excessive heat, as both can expel too much whey, leading to a drier, less squeaky product. Once the curds form, gently press them just enough to release excess liquid without compacting the structure. A good rule of thumb: if the curds feel slightly spongy to the touch, you’ve struck the right balance.

For a comparative perspective, consider the texture of halloumi or paneer, which are also springy but lack the squeak due to different protein treatments. Cheese curds’ unique texture comes from minimal processing—no stretching, brining, or pressing—allowing the natural protein and moisture interplay to shine. This simplicity is why curds are best enjoyed fresh, as a snack or in dishes like poutine, where their texture stands out.

Finally, if your curds have lost their squeak, don’t discard them. While they may not deliver the signature sound, they’re still excellent for melting into dishes like grilled cheese or casseroles. To revive a slight springiness, briefly soak them in warm (not hot) water for 10–15 seconds, then pat dry. This rehydrates the proteins without altering their flavor, giving you a second chance to enjoy their unique texture.

What is a Cheese Button? Unveiling the Mystery Behind This Quirky Gadget

You may want to see also

Production: Made by curdling milk with rennet or acid, then cutting and heating the curds

Cheese curds are the fresh, young form of cheese before it is aged or pressed, and their production hinges on a precise interplay of chemistry and technique. The process begins with curdling milk, a transformation triggered by either rennet or acid. Rennet, a complex of enzymes, is typically added at a rate of 1:10,000 (0.01% of the milk volume), while acid (such as vinegar or citric acid) is used in smaller quantities, often 1-2 tablespoons per gallon of milk. This curdling separates the milk into solid curds and liquid whey, a fundamental step in cheese-making.

Once the curds form, they are cut into smaller pieces to release moisture and create the desired texture. The size of the cut determines the final product: larger curds yield a softer cheese, while smaller cuts produce a firmer texture. For cheese curds, the curds are often cut into 1-inch cubes. After cutting, the curds are gently heated to expel more whey and firm up. This heating step is critical, as temperatures above 175°F (79°C) can toughen the curds, while insufficient heat leaves them too soft. The goal is to achieve a springy, squeaky consistency, a hallmark of fresh cheese curds.

The choice between rennet and acid significantly influences the flavor and texture of the curds. Rennet-coagulated curds tend to be smoother and milder, ideal for varieties like cheddar curds. Acid-coagulated curds, on the other hand, are tangier and crumblier, often used in cottage cheese or Latin American queso fresco. For home cheesemakers, rennet is preferred for its consistency, but acid offers a simpler, vegetarian-friendly alternative. Regardless of the method, the key is to monitor the curdling process closely, as over-acidification or excessive rennet can ruin the batch.

Practical tips for producing cheese curds include using fresh, high-quality milk for the best results and maintaining strict hygiene to prevent contamination. After heating, the curds should be rinsed in cold water to stop the cooking process and preserve their squeakiness. For those experimenting at home, starting with small batches (1-2 gallons of milk) allows for better control and quicker troubleshooting. Finally, fresh curds are best consumed within a few days, as they lose their signature texture and flavor over time. Master these steps, and you’ll unlock the simple yet satisfying art of making cheese curds.

Calories in a Chicken Cheese Steak Wheat Wrap: A Nutritional Breakdown

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Serving: Often eaten plain, fried, or paired with dishes like poutine or salads

Cheese curds, with their distinctive squeak and fresh, milky flavor, are a versatile ingredient that shines in various culinary contexts. When served plain, their simplicity allows the natural taste and texture to take center stage. Fresh curds, ideally consumed within 24 hours of production, offer a delightful contrast between their slightly rubbery exterior and creamy interior. For optimal enjoyment, let them come to room temperature to enhance their squeakiness—a hallmark of freshness. This unadulterated approach is particularly popular in regions like Wisconsin and Quebec, where cheese curds are a cultural staple.

Frying cheese curds transforms them into a decadent treat, elevating their texture and flavor profile. To achieve the perfect fried curd, coat them in a light batter (a mixture of flour, beer, and spices works well) and fry at 350°F (175°C) until golden brown. The result is a crispy exterior that gives way to a molten, gooey center. Pair them with a side of ranch dressing or spicy aioli for a crowd-pleasing appetizer. Pro tip: Use fresh curds for frying, as older ones may become greasy or lose their shape.

When paired with dishes like poutine, cheese curds become the star of a classic comfort food. Traditional Quebecois poutine combines crispy fries, rich gravy, and fresh cheese curds, creating a harmonious blend of textures and flavors. The key is to add the curds while the fries are still hot, allowing them to soften slightly without losing their squeak. For a modern twist, experiment with variations like pulled pork poutine or truffle gravy, keeping the curds as the unifying element. This dish is best enjoyed immediately to preserve the curds’ signature texture.

Incorporating cheese curds into salads adds a surprising element of richness and flavor. Toss them into a mixed green salad with cherry tomatoes, cucumbers, and a tangy vinaigrette for a refreshing yet satisfying meal. For heartier options, pair curds with roasted vegetables, nuts, or grains like quinoa. Their mild, milky taste complements both light and robust ingredients, making them a versatile addition to any salad. To maintain their texture, add the curds just before serving to prevent them from becoming soggy.

Whether enjoyed plain, fried, or as part of a larger dish, cheese curds offer a unique culinary experience that caters to a variety of tastes and occasions. Their adaptability makes them a favorite among both traditionalists and culinary innovators, ensuring their place in kitchens and menus worldwide.

Turkey Tom's Cheese-Free Change: Jimmy John's Decision Explained

You may want to see also

Regional Popularity: Especially popular in Wisconsin, Canada, and parts of the Midwest

Cheese curds, those squeaky, fresh morsels of dairy delight, have carved out a special place in the hearts—and stomachs—of people in specific regions. Wisconsin, often dubbed "America's Dairyland," stands as the undisputed epicenter of cheese curd culture. Here, they’re not just a snack but a way of life. From gas stations to fine dining, cheese curds are ubiquitous, often served deep-fried and paired with a side of ranch dressing. The state’s deep-rooted dairy industry ensures a steady supply of fresh curds, often sold within hours of production, maximizing their signature squeak.

Across the border, Canada shares this passion, particularly in Quebec, where *poutine* reigns supreme. This iconic dish—fries smothered in gravy and topped with cheese curds—relies on the curds’ unique texture to hold up against the hot gravy without melting completely. While poutine is a national treasure, Quebec’s curds are prized for their freshness and elasticity, often sourced from local cheesemakers. The dish’s popularity has spread across Canada, but Quebec remains its spiritual home, where curds are a symbol of regional pride.

In the broader Midwest, cheese curds enjoy a quieter but equally devoted following. States like Minnesota, Illinois, and Michigan embrace them as a staple at fairs, festivals, and sporting events. Here, the focus is often on experimentation—think curds infused with jalapeños, coated in beer batter, or even stuffed with meat. This creativity reflects the region’s willingness to adapt traditional dairy products to modern tastes, ensuring curds remain relevant across generations.

What sets these regions apart is their shared dairy heritage and climate, ideal for dairy farming. Wisconsin alone produces over 25% of the nation’s cheese, while Canada’s vast dairy cooperatives prioritize quality and tradition. For those outside these areas, seeking out local farmers’ markets or specialty shops is key to finding authentic curds. Pair them with a cold beer or enjoy them straight from the bag—just make sure they squeak when you bite in. That’s the mark of freshness.

Mastering Smoked Cheese: Traeger Techniques for Perfect Flavor and Texture

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Cheese curds are the fresh, moist, and slightly rubbery solids formed during the early stages of cheese making, before the cheese is pressed and aged.

Cheese curds are made by curdling milk with rennet or acid, separating the solids (curds) from the liquid (whey), and then gently cooking and draining them without pressing or aging.

Cheese curds have a mild, milky flavor with a slightly salty taste. They are known for their squeaky texture when fresh.

No, cheese curds are the precursor to aged cheese. They are fresher, softer, and have a unique texture compared to fully aged cheese.

Cheese curds are often eaten plain, battered and deep-fried (as in cheese curd fries), or used in dishes like poutine. They are also enjoyed as a snack or paired with beer.