Cheese rinds are the outer layers or coatings that form on certain types of cheese during the aging process, serving both a protective and functional purpose. They can vary widely in texture, appearance, and edibility, depending on the cheese variety and production method. Some rinds are naturally developed from bacteria or mold, while others are deliberately treated with wax, ash, or other substances to enhance flavor or preservation. Understanding cheese rinds is essential for appreciating the complexity of cheese-making and knowing whether they are meant to be eaten or removed before consumption.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | The outer layer or crust of a cheese wheel, formed during the aging process. |

| Composition | Can be made of natural molds, bacteria, yeast, or added wax, cloth, or plastic. |

| Texture | Varies from soft and edible to hard and inedible, depending on the cheese type. |

| Edibility | Some rinds are edible (e.g., Brie, Camembert) while others are not (e.g., Parmesan, aged Gouda). |

| Function | Protects the cheese from moisture loss and external contaminants; contributes to flavor development. |

| Types | Natural (bloomy, washed, hard), artificial (waxed, cloth-bound, plastic-coated). |

| Flavor Impact | Adds complexity, earthiness, or pungency to the cheese, depending on the rind type. |

| Aging Role | Influences the cheese's texture, flavor, and appearance during maturation. |

| Storage Impact | Helps regulate moisture and prevent spoilage during aging and storage. |

| Removal | Inedible rinds are typically removed before consumption; edible rinds may be eaten or left on. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Natural vs. Artificial Rinds: Distinguishes between rinds formed naturally during aging and those added artificially for texture

- Types of Cheese Rinds: Explores various rinds like bloomy, washed, natural, and waxed, each with unique traits

- Edibility of Rinds: Discusses which cheese rinds are safe to eat and which should be avoided

- Rind Formation Process: Details how rinds develop through aging, bacteria, mold, or external treatments

- Rind’s Role in Flavor: Explains how rinds protect cheese and contribute to its flavor and texture

Natural vs. Artificial Rinds: Distinguishes between rinds formed naturally during aging and those added artificially for texture

Cheese rinds are the outer layers that encase the cheese, serving as both a protective barrier and a contributor to flavor and texture. Among the various types, the distinction between natural and artificial rinds is pivotal for understanding their role in cheese production and consumption. Natural rinds develop organically during the aging process, influenced by factors like humidity, temperature, and microbial activity. These rinds often carry complex flavors and textures that reflect the cheese’s environment and craftsmanship. In contrast, artificial rinds are deliberately applied—wax, cloth, or plastic coatings—primarily to control moisture loss and introduce specific textures, often for aesthetic or functional purposes rather than flavor enhancement.

Consider the example of a traditional French Brie versus a mass-produced cheddar. The Brie’s natural rind, a result of mold growth (e.g., *Penicillium candidum*), is edible and contributes to its creamy interior and earthy notes. Conversely, the artificial wax rind on the cheddar is inedible, designed solely to preserve moisture and extend shelf life. This comparison highlights the functional and sensory trade-offs between natural and artificial rinds. While natural rinds are integral to the cheese’s character, artificial rinds prioritize practicality, often at the expense of authenticity.

For those crafting cheese at home, understanding this distinction is crucial. Natural rinds require careful aging conditions—specific humidity levels (around 85–90%) and temperatures (50–55°F)—to foster beneficial mold growth. Artificial rinds, however, offer a simpler approach: brushing melted wax (food-grade paraffin or cheese wax) in thin, even layers or wrapping the cheese in breathable materials like cheesecloth. The choice depends on the desired outcome: a nuanced, artisanal product or a consistent, shelf-stable one.

From a consumer perspective, knowing the rind type can guide usage. Natural rinds on cheeses like Camembert or Gruyère are often edible and enhance the eating experience, though some prefer to trim them. Artificial rinds, such as wax or plastic, should always be removed before consumption. For instance, slicing through the wax on a Gouda would introduce unwanted texture and potential contaminants. This awareness ensures both safety and enjoyment.

In the debate of natural versus artificial rinds, there’s no one-size-fits-all answer. Natural rinds celebrate the art of cheesemaking, offering depth and complexity, while artificial rinds cater to convenience and consistency. Whether you’re a cheesemaker or enthusiast, recognizing these differences empowers you to make informed choices, ensuring the rind complements the cheese rather than detracting from it.

Are Cheese Danishes Sweet? Exploring the Flavor Profile of This Pastry

You may want to see also

Types of Cheese Rinds: Explores various rinds like bloomy, washed, natural, and waxed, each with unique traits

Cheese rinds are the outer layers that protect and shape the cheese, often influencing its flavor, texture, and aging process. Among the most distinctive types are bloomy, washed, natural, and waxed rinds, each contributing uniquely to the cheese’s character. Understanding these rinds not only enhances appreciation but also guides proper handling and pairing.

Bloomy rinds, perhaps the most recognizable, are thin, velvety, and edible, formed by the introduction of *Penicillium camemberti* or *Penicillium candidum* during production. Examples include Brie and Camembert. These cheeses age from the exterior inward, developing a soft, creamy interior. To enjoy them, let the cheese sit at room temperature for an hour to allow the rind to soften, then spread it on crusty bread or pair with a crisp white wine. Avoid removing the rind, as it’s integral to the flavor profile.

In contrast, washed rinds are semi-soft to firm cheeses with a pungent aroma and orange-hued exterior, achieved by rinsing the rind with brine, wine, or beer during aging. This process encourages the growth of *Brevibacterium linens*, the same bacteria found on human skin. Notable examples are Époisses and Taleggio. When serving, cut away only the thickest parts of the rind if desired, but leave the rest to balance the rich, savory interior. Pair with a bold red wine or dark beer to complement its intensity.

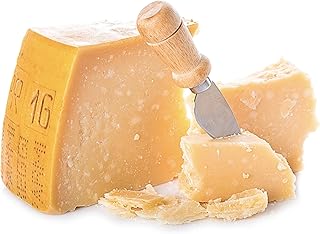

Natural rinds form organically as the cheese ages, often developing a hard, dry texture that may be inedible. Cheeses like aged Gouda or Parmigiano-Reggiano fall into this category. The rind acts as a protective barrier, concentrating flavors within. For cooking, the rind can be added to soups or broths to infuse umami richness, but it’s typically removed before eating. Store these cheeses in a cool, humid environment to prevent the rind from cracking.

Waxed rinds serve a purely functional purpose, sealing the cheese to halt aging and retain moisture. Cheddar and Gouda are often waxed for preservation. The wax is inedible and must be removed before consumption. To do so, use a sharp knife to carefully peel it away, taking care not to cut into the cheese. Waxed cheeses are versatile and pair well with fruits, nuts, or crackers, making them ideal for cheese boards.

Each rind type offers a distinct sensory experience, from the creamy indulgence of bloomy rinds to the robust punch of washed rinds. By understanding their characteristics, you can better select, store, and savor these cheeses, elevating any culinary occasion.

Mastering Cheese Board Care: Effective Cleaning Tips for Longevity

You may want to see also

Edibility of Rinds: Discusses which cheese rinds are safe to eat and which should be avoided

Cheese rinds, the outer layers of cheese, vary widely in edibility depending on the type of cheese and the method used to produce them. Understanding which rinds are safe to eat and which should be avoided is crucial for both culinary enjoyment and health. For instance, the rind of a natural, mold-ripened cheese like Brie is generally safe to consume and adds a complex flavor, while the wax coating on a Cheddar is purely protective and should be discarded.

Analytical Perspective:

The edibility of cheese rinds hinges on their composition and purpose. Natural rinds, formed by bacteria or mold during aging (e.g., Camembert, Gruyère), are typically edible and contribute to the cheese’s character. In contrast, artificial rinds, such as wax or plastic coatings, are inedible and serve only to preserve the cheese. Semi-soft cheeses like Taleggio have washed rinds that are safe to eat but may have a strong flavor that not everyone enjoys. Hard cheeses like Parmesan have rinds treated with oils or brine, which are edible but often too tough to chew comfortably.

Instructive Approach:

To determine if a rind is edible, consider its texture, appearance, and origin. Soft, bloomy rinds (e.g., Brie, Camembert) are usually safe and enhance the eating experience. Firm, natural rinds (e.g., Gruyère, Gouda) can be eaten but may be chewy. Avoid rinds that are excessively hard, waxy, or plastic-like, as these are non-edible coatings. For washed-rind cheeses (e.g., Époisses, Limburger), the rind is edible but has a pungent aroma, so consume it only if you enjoy bold flavors. Always check the cheese’s packaging or consult a cheesemonger for clarity.

Comparative Insight:

While natural rinds often add depth to a cheese’s flavor, their edibility varies by type. For example, the rind of a young, natural-aged cheese like young Gouda is softer and more palatable than the harder rind of an aged Comté. Conversely, the rind of a blue cheese like Roquefort is edible but may be too strong for some palates. In contrast, processed cheese rinds (e.g., those on vacuum-sealed singles) are always inedible and should be removed before consumption.

Practical Tips:

If you’re unsure about a rind’s edibility, start by tasting a small piece. For cheeses with edible rinds, pair them with complementary flavors—for instance, serve Brie with fruit or honey to balance its richness. When cooking with cheese, consider whether the rind will melt or become too tough. For example, grated Parmesan rind can be added to soups or sauces for extra flavor, but large pieces may not break down. Always store cheeses properly to maintain rind integrity; wrap natural-rind cheeses in wax paper to allow them to breathe, and keep coated cheeses in their original packaging until use.

By understanding the nuances of cheese rinds, you can confidently enjoy them as part of your culinary experience, ensuring both safety and satisfaction.

Mastering Fluffy Shredded Cheese: Simple Tips for Perfect Texture

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Rind Formation Process: Details how rinds develop through aging, bacteria, mold, or external treatments

Cheese rinds are the outer layers that form on cheese during the aging process, acting as a protective barrier while influencing texture and flavor. The rind’s development is a complex interplay of time, microorganisms, and external interventions, each contributing uniquely to its character. Understanding this process reveals how a simple curd transforms into a nuanced, rind-encased cheese.

Aging as the Foundation

Time is the silent architect of rind formation. As cheese ages, moisture evaporates from its surface, concentrating proteins and fats. This dehydration creates a firmer outer layer, often seen in natural rinds like those on aged Goudas or Cheddars. For example, a cheese aged 6 months will have a thinner, more pliable rind compared to one aged 2 years, which develops a harder, crystalline texture. Humidity and temperature control during aging are critical; too dry, and the rind cracks; too damp, and mold dominates prematurely.

Microbial Maestros: Bacteria and Mold

Microorganisms are the artists of rind formation, painting flavors and textures through metabolic activity. In washed-rind cheeses like Époisses, *Brevibacterium linens* bacteria are regularly brushed onto the surface with brine, creating a sticky, orange rind with a pungent aroma. Conversely, mold-ripened cheeses like Brie rely on *Penicillium camemberti*, which breaks down fats and proteins, yielding a bloomy, velvety rind. Dosage matters: a higher concentration of mold spores results in faster rind development but risks overpowering the cheese’s interior.

External Treatments: The Human Touch

Human intervention accelerates and directs rind formation. Wax-coated cheeses like Gouda are sealed to slow moisture loss, creating a smooth, edible rind. Ash-coated cheeses, such as Morbier, develop a dry, grayish rind that contrasts with the creamy interior. For blue cheeses, piercing the rind allows oxygen to penetrate, activating *Penicillium roqueforti* mold internally while the exterior remains relatively untouched. These treatments require precision; for instance, waxing too early traps excess moisture, leading to undesirable bacterial growth.

Practical Tips for Rind Appreciation

When selecting cheese, consider the rind’s role in flavor and safety. Natural rinds are often edible, adding complexity to dishes like grilled cheese or fondue. Washed rinds, while aromatic, should be removed if their flavor overwhelms the pairing. For home aging, maintain a consistent environment—50–55°F (10–13°C) and 85% humidity—to encourage gradual rind development. Regularly inspect for unwanted mold or drying, adjusting conditions as needed.

The rind formation process is a testament to the marriage of science and craftsmanship. Whether through aging, microbial activity, or external treatments, each rind tells a story of transformation, turning humble milk into a masterpiece of texture and taste.

Do Babybel Cheese Wheels Need Refrigeration? Storage Tips Revealed

You may want to see also

Rind’s Role in Flavor: Explains how rinds protect cheese and contribute to its flavor and texture

Cheese rinds are the outer layers that encase the cheese, acting as a protective barrier against external elements. They are not merely a wrapper but a dynamic component that significantly influences the cheese's flavor, texture, and overall character. Understanding their role reveals why some rinds are meant to be eaten, while others are best left on the board.

Consider the rind as the cheese’s first line of defense. During aging, it shields the interior from excessive moisture loss, mold growth, and contamination. For example, natural rinds on cheeses like Brie develop a bloom of *Penicillium camemberti*, a mold that not only protects the cheese but also contributes to its earthy, mushroom-like flavor. In contrast, waxed rinds on cheeses such as Gouda act as a physical barrier, slowing down moisture evaporation and ensuring a creamy texture inside. Without this protection, the cheese could dry out, crack, or spoil prematurely.

The rind’s contribution to flavor is both direct and indirect. In washed-rind cheeses like Époisses, the rind is regularly brushed with brine, encouraging the growth of *Brevibacterium linens*, a bacteria responsible for the cheese’s pungent aroma and savory taste. This process also creates a sticky, orange exterior that contrasts with the smooth, creamy interior. Similarly, in aged cheeses like Parmigiano-Reggiano, the rind develops complex flavors through prolonged aging, which can be shaved and used to add depth to dishes like pasta or salads. Even if the rind isn’t eaten, its interaction with the cheese during aging imparts nuanced flavors that permeate the interior.

Texture is another area where the rind plays a crucial role. Hard rinds, such as those on aged Alpine cheeses, prevent the interior from becoming too dry or brittle, allowing the cheese to maintain a dense yet crumbly texture. In soft-ripened cheeses like Camembert, the rind’s gradual breakdown creates a gooey, luscious center. For optimal enjoyment, pair the rind’s texture with the cheese’s interior—for instance, spread a rind-on Brie on crusty bread to balance the creamy interior with the slightly chewy, edible rind.

Practical tip: When serving cheese, consider the rind’s edibility and purpose. Natural and bloomy rinds (e.g., Brie, Camembert) are typically edible and enhance the experience. Washed rinds (e.g., Époisses, Taleggio) are also edible but have a stronger flavor that may not appeal to all. Waxed or cloth-bound rinds (e.g., Gouda, Cheddar) should be removed before eating. For aged cheeses like Parmesan, save the rind to flavor soups or broths—it adds umami richness without waste. By respecting the rind’s role, you elevate both the cheese and the dish.

Mastering the Art of Reconstituting Powdered Cheese: Tips and Tricks

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Cheese rinds are the outer layer or casing of a cheese, formed naturally or added during the cheesemaking process. They can vary in texture, thickness, and edibility depending on the type of cheese.

Some cheese rinds are edible, such as those on natural-rind cheeses like Brie or Camembert, while others, like wax or cloth-bound rinds, are not meant to be eaten. Always check the type of rind before consuming.

Cheese rinds serve multiple purposes, including protecting the cheese from mold, controlling moisture loss, and influencing flavor development during aging.

While the rind on hard cheeses like Parmesan is technically edible, it is often hard, flavorless, or too salty, so it is typically removed or used to flavor soups and sauces instead.

Cheese rinds can form naturally through aging and exposure to bacteria or molds, or they can be created artificially by waxing, cloth-wrapping, or brushing the cheese with solutions like brine or mold cultures.