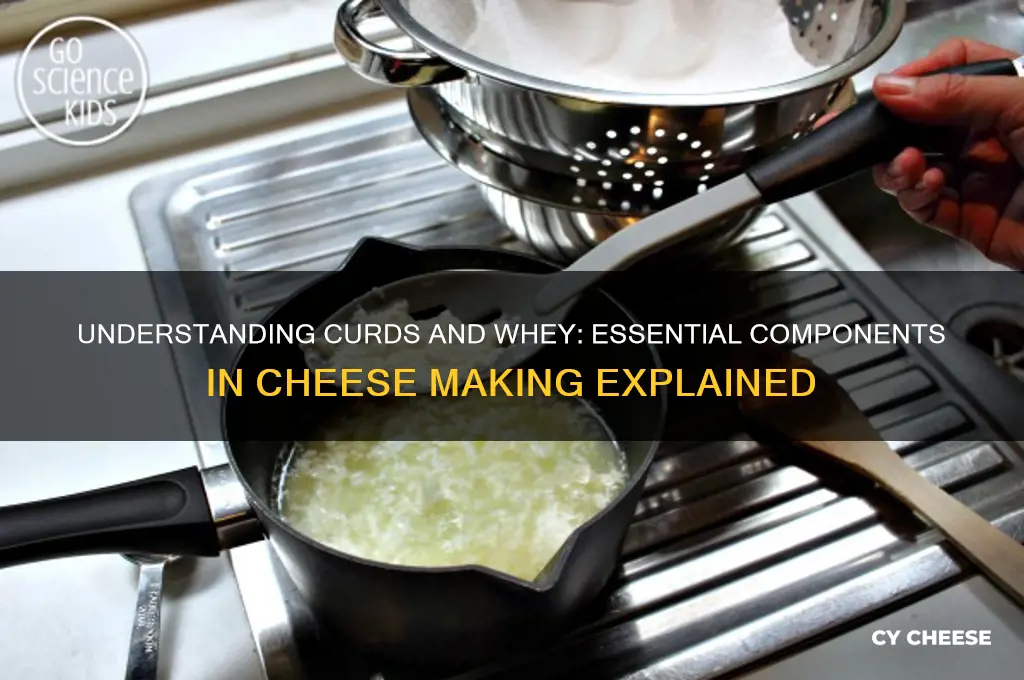

Curds and whey are fundamental components in the cheese-making process, representing the separation of milk into its solid and liquid parts. When milk is coagulated, either through the addition of rennet or acids like lemon juice or vinegar, it splits into curds—the solid, protein-rich masses that form the basis of cheese—and whey, the liquid byproduct that is mostly water, lactose, and minerals. This separation is a critical step in cheese production, as the curds are further processed, pressed, and aged to create various types of cheese, while whey is often utilized in other food products or as a nutritional supplement. Understanding the roles of curds and whey provides insight into the science and artistry behind cheese making.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Curds are the solid milk proteins (casein) that coagulate during cheese making, while whey is the liquid byproduct remaining after curds are separated. |

| Composition | Curds: Primarily casein proteins, fat, and some lactose. Whey: Water, lactose, whey proteins (e.g., beta-lactoglobulin, alpha-lactalbumin), vitamins, and minerals. |

| Role in Cheese Making | Curds form the basis of cheese, while whey is drained off and can be used in other products like whey protein powder or animal feed. |

| Texture | Curds: Solid, gelatinous, or crumbly depending on the cheese type. Whey: Thin, watery liquid. |

| Color | Curds: White or pale yellow (depending on milk type). Whey: Translucent or slightly opaque. |

| pH | Curds: Lower pH (acidic) due to coagulation. Whey: Slightly acidic but closer to neutral. |

| Nutritional Value | Curds: High in protein and fat. Whey: Rich in protein, lactose, and minerals like calcium and potassium. |

| Uses | Curds: Primary ingredient in cheese. Whey: Used in sports nutrition, baking, and as a food additive. |

| Separation Process | Curds and whey are separated through coagulation (using rennet or acid) and draining. |

| Environmental Impact | Whey is often considered a waste product in large-scale cheese making but can be repurposed to reduce environmental impact. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Curds Formation: Coagulated milk solids separate from whey during cheese making

- Whey Definition: Liquid byproduct remaining after curds are separated

- Coagulation Process: Enzymes or acids cause milk to curdle into curds

- Curds vs. Whey: Curds become cheese; whey is used in other products

- Whey Utilization: Whey is processed into protein powders, drinks, or animal feed

Curds Formation: Coagulated milk solids separate from whey during cheese making

Curds and whey are the two primary components that emerge when milk coagulates during cheese making. This separation is a critical step, transforming liquid milk into a solid cheese base. The curds, composed of milk proteins and fats, are the foundation of the cheese, while the whey is a nutrient-rich liquid byproduct. Understanding this process is essential for anyone looking to master cheese making or simply appreciate the science behind it.

The formation of curds begins with the addition of a coagulant, such as rennet or acid (e.g., lemon juice or vinegar), to milk. For example, in traditional cheese making, about 1/4 teaspoon of liquid rennet diluted in 1/4 cup of cool water is added to 1 gallon of milk. This coagulant triggers the milk’s casein proteins to bond together, forming a gel-like structure. Over time—typically 30 to 60 minutes depending on the recipe—this gel firms up, allowing the curds to separate from the whey. Temperature plays a crucial role here; milk should be warmed to around 86°F (30°C) for optimal coagulation, as lower temperatures can slow the process, while higher temperatures may denature the proteins.

Once the curds have formed, the next step is cutting them into smaller pieces to release more whey. This is done using a long-bladed knife or curd cutter, and the size of the cuts determines the final texture of the cheese. For example, smaller curds (about 1/2 inch) are ideal for hard cheeses like cheddar, while larger curds (1 inch or more) are used for softer cheeses like mozzarella. After cutting, the curds are gently stirred to expel additional whey, a process that can take anywhere from 10 to 40 minutes. This stage requires patience and precision, as over-stirring can break the curds, while under-stirring may leave excess whey, affecting the cheese’s consistency.

The separation of curds and whey is not just a mechanical process but a transformative one. As whey drains off, the curds consolidate, concentrating the milk’s solids and setting the stage for further cheese development. Whey, often discarded in home cheese making, is actually a valuable byproduct rich in protein, vitamins, and minerals. It can be used in smoothies, baked goods, or even as a fertilizer. Meanwhile, the curds are pressed, salted, and aged to develop flavor and texture, showcasing the remarkable journey from milk to cheese.

In summary, curd formation is a delicate balance of chemistry and technique. By controlling factors like coagulant type, temperature, and cutting size, cheese makers can manipulate the curds’ structure and ultimately the cheese’s character. Whether you’re a novice or an experienced cheese maker, mastering this step is key to crafting high-quality cheese. Practical tips, such as using a thermometer for precise temperature control and experimenting with different coagulants, can enhance your results and deepen your appreciation for this ancient craft.

Is Velveeta Cheese Actually Cheese? Organic Authority Explains

You may want to see also

Whey Definition: Liquid byproduct remaining after curds are separated

Whey, often overlooked in the cheese-making process, is the liquid byproduct that remains after the curds have been separated. This translucent, slightly yellowish fluid is not merely a waste product but a treasure trove of nutrients and versatility. Rich in protein, lactose, vitamins, and minerals, whey has been utilized for centuries in various culinary and health applications. Its separation from curds is a critical step in cheese production, marking the transformation of milk into solid cheese and liquid whey.

From a nutritional standpoint, whey is a powerhouse. It contains all nine essential amino acids, making it a complete protein source. Fitness enthusiasts often consume whey protein supplements to support muscle repair and growth, typically in doses ranging from 20 to 30 grams per serving. Beyond its protein content, whey is also a source of bioactive compounds like immunoglobulins and lactoferrin, which support immune function. For those intolerant to lactose, whey can still be beneficial when processed into isolates or hydrolysates, which have significantly reduced lactose levels.

In the kitchen, whey’s applications are surprisingly diverse. Traditionally, it has been used in baking to enhance the texture and nutritional profile of bread and pastries. Its acidity can also act as a natural leavening agent, replacing commercial starters in sourdough cultures. For home cooks, whey is an excellent tenderizer for meats and a base for fermenting vegetables like sauerkraut or pickles. A practical tip: store whey in the refrigerator for up to a week or freeze it in ice cube trays for longer-term use in smoothies or soups.

Comparatively, whey’s role in cheese making contrasts sharply with that of curds. While curds become the foundation of cheese, whey is often seen as a secondary product. However, its value lies in its adaptability. In regions like Scandinavia, whey is traditionally used to make beverages like *filmjölk*, a fermented milk drink. In contrast, modern industries repurpose whey into animal feed or process it into powdered supplements, reducing waste and maximizing economic efficiency.

To fully appreciate whey, consider its environmental impact. Historically, whey disposal was a challenge, as its high organic content could pollute water systems. Today, innovative solutions like anaerobic digestion convert whey into biogas, a renewable energy source. This shift not only minimizes waste but also aligns with sustainable practices in food production. Whether in health, cuisine, or ecology, whey’s definition as a byproduct belies its profound utility and potential.

Land O'Lakes American Cheese: Has the Recipe Changed?

You may want to see also

Coagulation Process: Enzymes or acids cause milk to curdle into curds

Milk's transformation into cheese begins with a delicate dance of chemistry, where curds and whey emerge as the stars. The coagulation process, a pivotal step in cheese making, relies on the strategic use of enzymes or acids to curdle milk, separating it into solid curds and liquid whey. This phase is not just a simple reaction but a nuanced interplay of factors that determine the texture, flavor, and overall quality of the final product.

Enzymes: The Precision Tools

Enzymes, particularly rennet, are the go-to agents for most cheese makers due to their precision and consistency. Derived from animal sources or produced through microbial fermentation, rennet contains chymosin, an enzyme that specifically targets kappa-casein, a protein in milk. When added at a typical dosage of 0.02–0.05% of milk volume, rennet initiates a slow, controlled coagulation, usually taking 30–60 minutes. This method is ideal for hard and semi-hard cheeses like Cheddar or Parmesan, as it produces a firm, elastic curd. For vegetarians or those avoiding animal products, microbial transgenic enzymes offer a suitable alternative, though they may yield slightly different textures.

Acids: The Quick Fix

Acids, such as lemon juice, vinegar, or citric acid, provide a faster, simpler route to curdling milk. These acids lower the milk’s pH, causing proteins to denature and coagulate. A common ratio is 1–2 tablespoons of lemon juice per gallon of milk, with curdling occurring within 5–10 minutes. While this method is convenient for fresh cheeses like ricotta or paneer, it results in a softer, more fragile curd and a tangy flavor profile. Acid-coagulated cheeses are typically ready to eat immediately, making them a favorite for home cheese making.

Comparing the Two: Texture and Flavor

The choice between enzymes and acids hinges on the desired cheese type. Enzyme-coagulated curds retain more moisture and have a smoother mouthfeel, essential for aged cheeses. Acid-coagulated curds, on the other hand, are drier and crumbly, perfect for fresh applications. Flavor-wise, enzymes impart a neutral or slightly nutty taste, while acids introduce a pronounced tartness. Understanding these differences allows cheese makers to tailor their approach to the specific cheese they aim to create.

Practical Tips for Success

Temperature control is critical during coagulation. Milk should be warmed to 30–37°C (86–98°F) for enzymes and 70–80°C (158–176°F) for acids to ensure optimal activity. Overheating or underheating can lead to weak curds or incomplete coagulation. Additionally, gentle stirring after adding the coagulant ensures even distribution, preventing uneven curdling. For beginners, starting with acid-coagulated cheeses like ricotta offers a low-stakes entry point, while enzyme-based methods provide a deeper dive into the art of cheese making.

Mastering the coagulation process is key to unlocking the potential of curds and whey. Whether using enzymes for precision or acids for speed, the right technique transforms humble milk into a culinary masterpiece.

Colby Jack Cheese WW Points: A Quick Nutrition Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Curds vs. Whey: Curds become cheese; whey is used in other products

In the alchemy of cheese making, milk transforms into two distinct substances: curds and whey. Curds, the solid masses that form when milk coagulates, are the foundation of cheese. Whey, the liquid byproduct left after curds are separated, is far from waste—it’s a versatile ingredient in its own right. This division marks the beginning of two separate journeys: one toward the rich, varied world of cheeses, and the other into a spectrum of products from protein supplements to baked goods.

Consider the process: after adding rennet or acid to milk, curds clump together, trapping fat and protein, while whey, primarily composed of water, lactose, and minerals, is drained off. Curds are then pressed, aged, and transformed into cheeses like cheddar, mozzarella, or gouda. Each cheese’s texture, flavor, and aroma depend on how curds are handled—temperature, moisture content, and aging time are critical. For example, fresh cheeses like ricotta retain more moisture, while hard cheeses like parmesan are pressed and aged for months, intensifying their flavor.

Whey, often overlooked, is a nutritional powerhouse. It contains about 20% of milk’s protein, including all essential amino acids, making it a staple in sports nutrition. Whey protein isolates, for instance, contain 90–95% protein per serving, ideal for muscle recovery. Beyond supplements, whey is used in bread and pastries to improve texture and shelf life, or fermented into beverages like kefir. Its lactose content also makes it a base for animal feed, ensuring minimal waste in dairy production.

The contrast between curds and whey highlights their complementary roles. While curds demand precision and artistry to become cheese, whey’s utility lies in its adaptability. For home cheese makers, saving whey isn’t just eco-friendly—it’s practical. Use it as a substitute for water in dough to enhance flavor, or blend it into smoothies for a protein boost. Understanding this duality not only deepens appreciation for cheese making but also unlocks creative ways to repurpose every part of the process.

Palmetto Cheese Owner's Bold Statement: What Did Brian Henry Say?

You may want to see also

Whey Utilization: Whey is processed into protein powders, drinks, or animal feed

Whey, the liquid byproduct of cheese making, was once considered waste, discarded after the curds were separated. Today, it’s a goldmine of nutrition, repurposed into high-value products that span industries. Its transformation begins with filtration and drying, isolating proteins like alpha-lactalbumin and beta-lactoglobulin, which boast a biological value comparable to eggs. This process yields whey protein concentrate (WPC), isolate (WPI), or hydrolysate, each varying in protein content (35-95%) and application. For instance, WPI, with its 90%+ protein purity, is ideal for post-workout recovery, while WPC, at 35-80%, suits smoothies and baking.

Consider the practicalities of incorporating whey into daily life. A 30g scoop of whey protein powder provides 25g of protein, meeting 50% of the daily requirement for an average adult. Athletes and older adults, who need 1.2-1.6g of protein per kg of body weight, can benefit from a morning shake or post-exercise drink. For those avoiding powders, ready-to-drink whey beverages offer convenience, though they often contain added sugars—check labels for options with <5g per serving. Even in cooking, whey protein can replace 10-20% of flour in recipes, enhancing the nutritional profile of pancakes or muffins without compromising texture.

The environmental and economic implications of whey utilization are equally compelling. Annually, the dairy industry generates 180 million tons of whey, which, if untreated, can pollute water bodies due to its high biochemical oxygen demand. By converting whey into protein powders or animal feed, manufacturers reduce waste and create a sustainable revenue stream. For livestock, whey-based feed improves milk yield in dairy cows by up to 10% and enhances meat quality in poultry. This dual benefit—ecological preservation and agricultural efficiency—positions whey as a cornerstone of circular economies in food production.

Finally, the global market for whey products is booming, driven by health trends and innovation. In 2022, the whey protein market was valued at $12 billion, projected to grow by 7% annually through 2030. Emerging applications, like whey-derived bioactive peptides for immune support or skincare, further expand its potential. For consumers, this means more choices—from protein bars fortified with whey hydrolysate for rapid absorption to hypoallergenic infant formulas enriched with whey fractions. As technology advances, whey’s role in nutrition and sustainability will only deepen, making it a resource too valuable to ignore.

Tangy Cheese Delights: Crafting Hearty, Flavorful Sandwiches to Savor

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Curds are the solid milk proteins (casein) that coagulate during cheese making, while whey is the liquid byproduct that separates from the curds.

Curds and whey are formed when milk is acidified (with bacteria or acid) or coagulated (with rennet), causing the milk proteins to clump together (curds) and release liquid (whey).

Curds are the foundation of cheese; they are pressed, salted, and aged to create the final cheese product, determining its texture, flavor, and structure.

Yes, whey is rich in protein and lactose and is often used in products like whey protein powder, ricotta cheese, or as a food additive.