Cheese production, while a centuries-old craft, is not without its challenges. From the initial stages of milk selection and coagulation to the final aging process, numerous issues can arise that affect the quality, texture, and flavor of the final product. Common problems include bacterial contamination, improper curd formation, uneven pH levels, and inadequate moisture control, all of which can lead to off-flavors, spoilage, or undesirable textures. Additionally, factors such as temperature fluctuations, inconsistent aging conditions, and the use of subpar ingredients can further complicate the process. Understanding and addressing these issues is crucial for both artisanal cheesemakers and large-scale producers to ensure a consistent and high-quality end product.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| pH Imbalance | Improper pH levels can lead to poor curd formation, bitter taste, or slow coagulation. Ideal pH for cheese making is typically between 6.4 and 6.6. |

| Temperature Control | Fluctuations in temperature during curdling, stretching, or aging can result in uneven texture, off-flavors, or bacterial growth. Optimal temperatures vary by cheese type. |

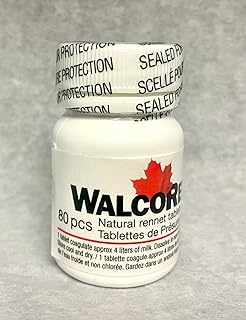

| Coagulant Overuse/Underuse | Too much rennet or coagulant can cause a tough, rubbery texture, while too little can prevent proper curd formation. |

| Bacterial Contamination | Unwanted bacteria can cause spoilage, off-flavors, or health risks. Proper sanitation and starter cultures are critical. |

| Moisture Content | Incorrect moisture levels can lead to mold growth, texture issues, or spoilage. Control is achieved through pressing, salting, and aging. |

| Salt Concentration | Improper salting can affect flavor, preservation, and texture. Too much salt can overpower the cheese, while too little can encourage spoilage. |

| Aging Time | Insufficient or excessive aging can result in underdeveloped flavors, overly strong flavors, or texture issues. |

| Curd Handling | Rough handling during cutting, stirring, or pressing can lead to a grainy texture or uneven moisture distribution. |

| Milk Quality | Poor-quality milk (e.g., high somatic cell count, antibiotics) can affect flavor, texture, and curd formation. |

| Humidity Control | Incorrect humidity during aging can cause mold growth, drying, or uneven ripening. Ideal humidity varies by cheese type. |

| Enzyme Activity | Inconsistent enzyme activity (e.g., lipase, protease) can lead to flavor imbalances or texture issues. |

| Air Exposure | Excessive air exposure during aging can cause oxidation, off-flavors, or surface discoloration. |

| Equipment Sanitation | Poorly sanitized equipment can introduce contaminants, affecting flavor, safety, and shelf life. |

| Starter Culture Viability | Inactive or weak starter cultures can result in slow fermentation, off-flavors, or failed batches. |

| Packaging Issues | Improper packaging can lead to mold growth, drying, or contamination during storage and distribution. |

Explore related products

$8.8 $15.99

What You'll Learn

- Contamination Risks: Bacteria, mold, or unwanted microbes can spoil cheese during production or aging

- Curdling Problems: Improper coagulation leads to weak texture or incomplete separation of curds and whey

- pH Imbalances: Incorrect acidity levels affect flavor, texture, and preservation of the cheese

- Salt Overuse: Excess salt can overpower taste, hinder fermentation, or cause texture issues

- Aging Challenges: Improper humidity, temperature, or time results in off-flavors or spoilage

Contamination Risks: Bacteria, mold, or unwanted microbes can spoil cheese during production or aging

Cheese production is a delicate dance with microbiology, where desired cultures transform milk into a culinary masterpiece, but unwanted guests can quickly turn it into a spoiled mess. Contamination risks from bacteria, mold, and other microbes are ever-present threats, capable of ruining batches and posing health hazards. Understanding these risks and implementing preventive measures are crucial for any cheesemaker, whether crafting a wheel of cheddar or a soft, creamy brie.

The Culprits: A Microscopic Menace

Imagine a bustling city, but instead of people, it's teeming with microscopic organisms. This is the environment within cheese during production and aging. While some bacteria and molds are essential for flavor and texture development, others are unwelcome intruders. *Listeria monocytogenes*, for instance, can cause severe foodborne illness, while *E. coli* can lead to gastrointestinal distress. Molds like *Penicillium roqueforti* are desirable in blue cheese, but other molds can produce harmful mycotoxins.

Even seemingly harmless bacteria can spoil cheese by producing off-flavors or causing unwanted fermentation. Understanding the specific microbes present and their potential impact is the first step in mitigating contamination risks.

Preventing the Invasion: A Multi-Pronged Approach

Think of cheese production as a fortress under siege. Rigorous sanitation is the first line of defense. This includes meticulous cleaning and disinfection of all equipment, utensils, and surfaces that come into contact with the cheese. Employees must practice good hygiene, including frequent handwashing and wearing clean clothing.

Temperature control is another critical weapon. Most unwanted microbes thrive in warmer temperatures, so maintaining proper chilling throughout production and aging is essential. Specific cheese varieties require precise temperature ranges for optimal flavor development while inhibiting harmful bacteria.

The Art of Balance: Encouraging the Good, Discouraging the Bad

Cheesemaking is as much art as science. Selecting the right starter cultures is crucial. These beneficial bacteria compete with unwanted microbes for resources, creating an environment hostile to spoilers. Some cheeses rely on surface molds for flavor and texture, but careful monitoring and control are necessary to prevent the growth of harmful varieties.

Vigilance is Key: Monitoring and Response

Despite best efforts, contamination can occur. Regular sensory evaluation – inspecting cheese for off-odors, discoloration, or unusual textures – is vital. More advanced techniques like microbial testing can provide early warning signs of potential problems. If contamination is suspected, swift action is necessary, which may involve discarding affected batches or implementing corrective measures to salvage the cheese if possible.

I Was a Cheese Sandwich: Unraveling the Early 90s Cult Classic

You may want to see also

Curdling Problems: Improper coagulation leads to weak texture or incomplete separation of curds and whey

Improper coagulation is a silent saboteur in the art of cheesemaking, often resulting in a weak, crumbly texture or a frustratingly incomplete separation of curds and whey. This issue can stem from a variety of factors, including incorrect rennet dosage, fluctuating milk temperature, or even the pH level of the milk. For instance, using too little rennet (less than 1/8 teaspoon per gallon of milk) can leave curds too soft, while excessive amounts (over 1/4 teaspoon per gallon) may cause them to become tough and rubbery. Achieving the right balance is critical, as it directly influences the cheese’s final structure and mouthfeel.

Consider the role of temperature in this delicate process. Milk heated below the optimal range (typically 86–100°F, depending on the cheese type) may not coagulate evenly, leading to a grainy texture. Conversely, overheating can denature proteins, causing curds to shrink and expel too much whey prematurely. For example, cheddar curds require a precise temperature window of 88–90°F to develop their characteristic firmness. A digital thermometer is an indispensable tool here, ensuring accuracy within ±1°F to avoid these pitfalls.

PH levels also play a pivotal role in coagulation. Milk with a pH above 6.7 may resist curdling altogether, while a pH below 6.5 can cause curds to form too quickly, resulting in a dense, unyielding texture. Acidifying agents like starter cultures must be added judiciously, following the recipe’s guidelines. For instance, a mesophilic starter culture typically lowers milk pH by 0.2–0.3 units over 45–60 minutes, creating an ideal environment for rennet to act effectively. Monitoring pH with test strips or a meter can prevent these issues before they escalate.

To troubleshoot curdling problems, start by auditing your process. Ensure rennet is fresh and stored properly (refrigerated, away from light) to maintain its potency. If using raw milk, test its acidity beforehand, as high bacterial counts can interfere with coagulation. For those working with pasteurized milk, consider adding calcium chloride (1/4 teaspoon per gallon) to restore mineral balance lost during processing. Finally, allow curds to rest undisturbed for 5–10 minutes post-cutting to ensure complete separation from whey. These steps, when executed with precision, can transform a disappointing batch into a masterpiece of texture and flavor.

Authentic Cheese: How to Spot the Real Deal in 5 Steps

You may want to see also

pH Imbalances: Incorrect acidity levels affect flavor, texture, and preservation of the cheese

Cheese making is a delicate dance of microbiology and chemistry, where pH plays a starring role. Even a slight deviation from the optimal pH range can wreak havoc on the final product. Imagine a cheddar that crumbles like dust instead of melting into gooey perfection, or a mozzarella that lacks the stretchy elasticity needed for pizza. These are just a few consequences of pH imbalances during cheese production.

Understanding the ideal pH range for each cheese type is crucial. For example, hard cheeses like Parmesan thrive in a lower pH environment (around 5.0-5.5), while softer cheeses like Brie prefer a slightly higher pH (around 6.0-6.5). This pH level directly influences the activity of lactic acid bacteria, which are responsible for acidifying the milk and contributing to flavor development.

Let's delve into the practical implications. During the curdling process, a pH meter becomes your most valuable tool. Aim for a target pH within the specific range for your chosen cheese. If the pH drops too low, the curd can become too acidic, leading to a bitter taste and a crumbly texture. Conversely, a pH that's too high can result in a soft, runny curd and a bland flavor profile. Adjustments can be made by adding specific amounts of starter cultures or acids like citric acid, but precision is key. A mere 0.1 pH unit difference can significantly impact the outcome.

Troubleshooting Tip: If you notice your cheese isn't developing the desired texture or flavor, test the pH of the whey (the liquid leftover after curdling). This can provide valuable clues about the acidity level and guide your adjustments.

The impact of pH extends beyond taste and texture; it's also a preservation issue. Lower pH levels create an environment hostile to spoilage bacteria, acting as a natural preservative. This is why aged cheeses with lower pH levels have a longer shelf life. However, if the pH is too high, spoilage bacteria can thrive, leading to off-flavors, mold growth, and potential health risks.

Preventative Measure: Maintaining proper sanitation throughout the cheese-making process is essential to prevent bacterial contamination that can further disrupt pH balance.

In essence, mastering pH control is akin to mastering the art of cheese making itself. It requires attention to detail, careful monitoring, and a willingness to adjust based on observations. By understanding the science behind pH and its impact on flavor, texture, and preservation, you'll be well on your way to crafting cheeses that are not just edible, but truly exceptional.

Does a Reuben Sandwich Include Cheese? Unraveling the Classic Deli Debate

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Salt Overuse: Excess salt can overpower taste, hinder fermentation, or cause texture issues

Salt is a critical ingredient in cheesemaking, serving as a preservative, flavor enhancer, and microbial controller. However, its overuse can disrupt the delicate balance required for successful cheese production. Excess salt can overpower the natural flavors of the milk, masking the subtle notes that develop during fermentation. For instance, in soft cheeses like Brie, a heavy hand with salt can drown out the creamy, earthy undertones, leaving a one-dimensional taste profile. This imbalance not only diminishes the sensory experience but also undermines the artisan’s intent to craft a nuanced product.

The impact of salt overuse extends beyond flavor, significantly hindering the fermentation process. Lactic acid bacteria, essential for transforming milk into cheese, are highly sensitive to salt concentrations. Studies show that salt levels exceeding 2-3% by weight can inhibit bacterial activity, slowing or even halting fermentation. In hard cheeses like Cheddar, this delay can result in incomplete acid development, leading to a crumbly texture and reduced shelf life. For cheesemakers, this means wasted time, resources, and potential product failure, highlighting the need for precise salt measurement and application.

Texture issues are another consequence of salt overuse, particularly in moist cheeses. Excess salt draws moisture out of the curd through osmosis, causing the cheese to become dry and brittle. Fresh cheeses like mozzarella or ricotta are especially vulnerable, as their high water content makes them more susceptible to salt-induced dehydration. To mitigate this, cheesemakers should adhere to recommended salt dosages—typically 1-2% of the curd weight—and evenly distribute salt by gently mixing it into the curds rather than applying it topically. This ensures a balanced texture without sacrificing moisture.

Practical tips can help cheesemakers avoid the pitfalls of salt overuse. First, always measure salt by weight, not volume, to ensure consistency. Second, consider the salt content of additional ingredients, such as brines or flavored coatings, to avoid cumulative excess. Third, taste-test small batches before scaling up production to fine-tune salt levels. For aged cheeses, remember that salt concentration intensifies as moisture evaporates, so start with a slightly lower dosage. By treating salt as a precision tool rather than a catch-all additive, cheesemakers can preserve the integrity of their craft and deliver a superior product.

Sausage and Cheese Plate Names: A Tasty Charcuterie Guide

You may want to see also

Aging Challenges: Improper humidity, temperature, or time results in off-flavors or spoilage

Cheese aging is a delicate dance where humidity, temperature, and time must harmonize perfectly. Even slight deviations can lead to off-flavors or spoilage, undermining months of careful craftsmanship. For instance, a humidity level below 80% can cause the cheese rind to dry out, halting the aging process and creating a hard, unappetizing exterior. Conversely, humidity above 90% can encourage mold growth beyond the desired varieties, leading to bitter or ammonia-like flavors.

Consider the role of temperature: ideal ranges vary by cheese type, but generally fall between 50°F and 58°F (10°C and 14°C). A temperature just 5°F too high can accelerate aging, resulting in a crumbly texture and sharp, overpowering flavors. Too low, and the enzymes responsible for flavor development slow down, leaving the cheese bland and underdeveloped. For example, a Gruyère aged at 45°F (7°C) may never achieve its signature nutty complexity, while one aged at 65°F (18°C) could become unpleasantly pungent in half the expected time.

Time is equally critical, as rushing or extending the aging process can ruin the final product. A cheese aged for too short a period may lack depth, while over-aging can lead to excessive ammonia flavors or a texture so hard it becomes inedible. Take Parmigiano-Reggiano, which requires a minimum of 12 months to develop its granular texture and savory profile. Age it for 18 months, and it becomes a premium product; age it for 24 months, and it risks becoming overly brittle and sharp.

Practical tips for home cheesemakers include investing in a hygrometer and thermometer to monitor conditions closely. For humidity control, place a bowl of water in the aging space or use a humidifier if levels drop below 80%. If temperature fluctuates, consider a wine fridge or cooler with adjustable settings. Regularly inspect the cheese for unwanted mold or texture changes, and adjust the environment as needed. Remember, aging is as much an art as a science—patience and precision are key to unlocking a cheese’s full potential.

Cheesy Banter: What Did One Cheese Say to the Other?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Common issues include improper curd formation, excessive bitterness, uneven texture, mold growth, and off-flavors due to bacterial contamination or incorrect pH levels.

A rubbery texture often results from over-stirring the curds, excessive heat during cooking, or using too much rennet. Proper temperature control and gentle handling of curds can prevent this.

Off or bitter flavors can stem from using spoiled milk, improper starter culture ratios, over-acidification, or contamination by unwanted bacteria. Ensuring clean equipment and accurate measurements is crucial.

Poor curd formation can be caused by insufficient rennet, low milk quality, incorrect temperature, or inadequate calcium levels. Testing milk quality and following precise recipes can help resolve this issue.

Mold growth can be prevented by maintaining proper humidity and temperature in the aging environment, regularly turning the cheese, and using mold-inhibiting solutions like brine or wax coatings.