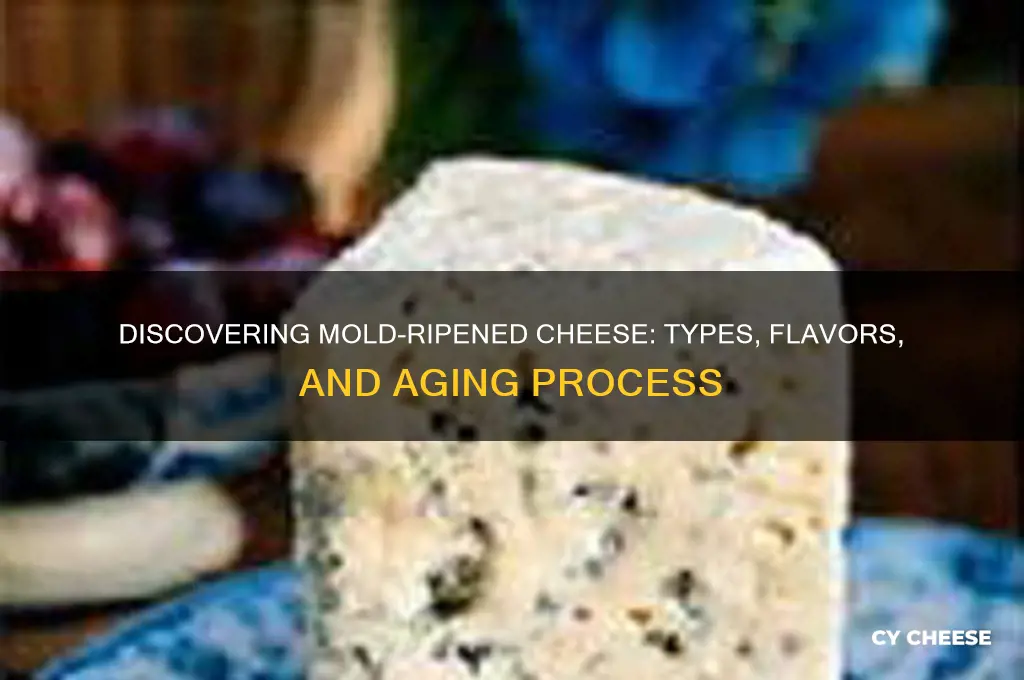

Mold-ripened cheeses are a distinctive category of cheeses characterized by the presence of specific molds that play a crucial role in their ripening process. Unlike other cheeses where mold is often undesirable, these cheeses intentionally cultivate molds such as *Penicillium camemberti* or *Penicillium roqueforti* to develop their unique flavors, textures, and aromas. The molds can grow on the surface (as in Brie or Camembert), throughout the interior (as in Blue Cheese), or both, creating a range of styles from creamy and mild to pungent and crumbly. This traditional method of cheesemaking results in complex, rich profiles that have made mold-ripened cheeses a favorite among connoisseurs worldwide.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Cheese ripened by the action of mold, either on the surface or internally. |

| Types | Surface-ripened (e.g., Brie, Camembert) and internally ripened (e.g., Blue Cheese). |

| Texture | Ranges from soft and creamy (surface-ripened) to semi-soft or crumbly (blue cheese). |

| Flavor Profile | Rich, earthy, nutty, and sometimes pungent, depending on the mold type. |

| Mold Types | Penicillium camemberti (surface), Penicillium roqueforti (blue cheese). |

| Ripening Process | Mold grows on the surface or internally, breaking down curds and adding flavor. |

| Appearance | Surface-ripened: white mold rind; Blue cheese: veined with blue or green mold. |

| Aging Time | Varies; typically 2-8 weeks for surface-ripened, longer for blue cheese. |

| Fat Content | Generally high, contributing to creamy texture. |

| Storage | Requires refrigeration; best stored in wax paper or cheese paper. |

| Pairings | Pairs well with fruits, nuts, crusty bread, and wines like Chardonnay or Port. |

| Health Considerations | Contains beneficial bacteria and mold cultures; may not be suitable for mold-sensitive individuals. |

| Examples | Brie, Camembert, Roquefort, Gorgonzola, Stilton. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Mold Types: Penicillium camemberti, Penicillium roqueforti, and others create distinct flavors and textures

- Ripening Process: Mold grows externally or internally, breaking down cheese curds over weeks to months

- Texture Variations: Ranges from soft (Brie) to semi-soft (Camembert) and blue-veined (Gorgonzola)

- Flavor Profiles: Earthy, nutty, tangy, or pungent, depending on mold type and aging time

- Popular Examples: Brie, Camembert, Roquefort, Gorgonzola, and Saint-André

Mold Types: Penicillium camemberti, Penicillium roqueforti, and others create distinct flavors and textures

Mold-ripened cheeses owe their distinctive flavors and textures to specific strains of mold, each contributing unique characteristics. Among these, *Penicillium camemberti* and *Penicillium roqueforti* are the most renowned, but other molds also play significant roles in crafting these artisanal delights. Understanding these molds is key to appreciating the diversity within this cheese category.

Penicillium camemberti is the star behind soft, bloomy-rind cheeses like Camembert and Brie. This mold works its magic on the cheese’s surface, creating a velvety white rind as it breaks down fats and proteins. The result? A creamy interior with earthy, mushroom-like flavors and a slight tang. To achieve this, the mold is introduced during the cheesemaking process, either by spraying the curds or adding it directly to the milk. Aging typically lasts 3–4 weeks, during which the rind softens and the interior ripens to a luscious consistency. For home enthusiasts, maintaining a consistent temperature of 50–55°F (10–13°C) and 90% humidity is crucial for optimal mold growth.

In contrast, *Penicillium roqueforti* transforms cheeses like Roquefort, Gorgonzola, and Stilton into bold, veined masterpieces. This mold thrives internally, creating distinctive blue or green veins as it penetrates the cheese. The flavor profile is sharper, with notes of pepper, nuts, and a salty finish. The process begins by inoculating the curds or piercing the cheese to allow air pockets for mold growth. Aging takes longer, often 2–4 months, in cool, humid environments around 45–50°F (7–10°C). A pro tip for pairing: the robust flavors of *P. roqueforti* cheeses complement sweet accompaniments like honey or fresh fruit.

Beyond these two powerhouses, other molds contribute to lesser-known but equally fascinating cheeses. *Penicillium candidum*, for instance, creates the thin, chalky rind of cheeses like Saint-Marcellin, offering a milder, lactic flavor. *Geotrichum candidum*, found in cheeses like Humboldt Fog, produces a flaky, edible rind with a yeasty, almost citrusy undertone. These molds highlight the versatility of mold-ripened cheeses, proving that even subtle differences in mold type can yield vastly different results.

When experimenting with mold-ripened cheeses, consider the mold’s role in both flavor and texture. For instance, *P. camemberti* cheeses are best enjoyed at room temperature to enhance their creamy mouthfeel, while *P. roqueforti* cheeses can be crumbled over salads or melted into sauces for a punch of flavor. Whether you’re a cheesemaker or a connoisseur, understanding these molds unlocks a deeper appreciation for the art and science behind these cheeses.

Is Piquant Cheese Spicy? Exploring Its Tangy, Peppery Flavor Profile

You may want to see also

Ripening Process: Mold grows externally or internally, breaking down cheese curds over weeks to months

Mold-ripened cheeses owe their distinctive flavors and textures to a meticulous ripening process driven by fungal activity. This transformation begins with the introduction of specific mold cultures, either on the cheese's surface or within its interior. These molds secrete enzymes that gradually break down the cheese curds, converting complex proteins and fats into simpler compounds that contribute to the cheese's characteristic taste and aroma. The duration of this process, ranging from weeks to months, is critical, as it determines the cheese's final texture—from soft and creamy to firm and crumbly—and its flavor profile, which can range from mild and earthy to pungent and bold.

Externally ripened cheeses, such as Brie and Camembert, develop a velvety rind as mold grows on their surface. This rind acts as a protective barrier while the mold's enzymes penetrate the cheese, softening it from the outside in. To encourage even ripening, these cheeses are often turned regularly during aging. For optimal results, maintain a humidity level of 85–90% and a temperature of 50–55°F (10–13°C) in the aging environment. Avoid overcrowding the cheeses, as proper air circulation is essential to prevent unwanted bacterial growth.

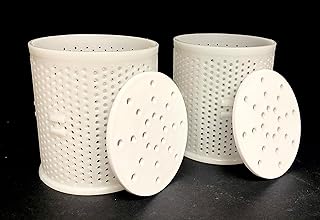

Internally ripened cheeses, like Blue Cheese, achieve their veined appearance through the deliberate introduction of mold spores into the curd before pressing. As the cheese ages, the mold grows inward, creating pockets of flavor and texture contrast. This method requires precise control over moisture and airflow to ensure the mold develops evenly. For home cheesemakers, inoculating the curd with Penicillium roqueforti spores at a rate of 0.05–0.1% of the milk weight is a common practice. Monitor the cheese closely during the first two weeks, as this is when the mold establishes itself most actively.

The ripening process is as much art as science, demanding patience and attention to detail. For instance, over-ripening can lead to ammonia-like off-flavors, while under-ripening may result in a bland, unremarkable cheese. To gauge readiness, observe the cheese's texture and aroma: a ripe Brie should yield to gentle pressure, while a mature Cheddar should have a slightly granular mouthfeel. Keep a ripening log to track changes, noting temperature, humidity, and sensory observations. This record will help refine future batches and ensure consistency.

Comparing the two ripening methods highlights their unique contributions to cheese diversity. Externally ripened cheeses often have a milder, more approachable flavor, making them ideal for beginners or those with less adventurous palates. Internally ripened cheeses, with their bold, complex profiles, cater to connoisseurs seeking depth and intensity. Regardless of method, the ripening process is a testament to the transformative power of mold, turning simple curds into culinary masterpieces. By understanding and controlling this process, cheesemakers can craft products that delight both novice and seasoned cheese enthusiasts alike.

Is Deli Cheese Real? Uncovering the Truth Behind Your Sandwich

You may want to see also

Texture Variations: Ranges from soft (Brie) to semi-soft (Camembert) and blue-veined (Gorgonzola)

Mold-ripened cheeses showcase a remarkable spectrum of textures, each a testament to the interplay of milk type, aging, and mold cultivation. At one end lies the indulgent softness of Brie, its interior yielding like a spoonful of crème fraîche, a result of Penicillium camemberti’s surface ripening. Contrast this with Camembert, slightly firmer yet still semi-soft, its paste creamy but with a subtle resistance that holds its shape when sliced. These cheeses owe their textures to controlled aging—typically 4 to 6 weeks—allowing the mold to break down curds without liquefying them entirely. For optimal enjoyment, serve Brie at room temperature (60–65°F) to enhance its melt-in-your-mouth quality, while Camembert benefits from a slightly cooler 55–60°F to maintain its structure.

Blue-veined cheeses like Gorgonzola introduce a different textural dynamic, where pockets of mold create a semi-soft to crumbly interior. The veins of Penicillium roqueforti or Penicillium glaucum not only impart bold flavor but also disrupt the curd’s uniformity, resulting in a cheese that can range from spreadable (young Gorgonzola Dolce) to firm and granular (aged Gorgonzola Piccante). Aging plays a critical role here: younger versions retain moisture and softness, ideal for spreading on crusty bread, while older specimens develop a drier, more brittle texture suited for grating over pasta. To preserve texture, store blue cheeses in wax paper, not plastic, to allow breathability without drying out.

The transition from soft to semi-soft to blue-veined textures is not arbitrary but a deliberate outcome of cheesemaking techniques. Soft cheeses like Brie are often made with higher moisture content and shorter aging, while semi-soft varieties like Camembert strike a balance between moisture retention and mold activity. Blue cheeses, however, are pierced during aging to introduce mold spores, creating veins that alter both flavor and texture. For home experimentation, try pairing textures with contrasting accompaniments: soft Brie with crisp apples, semi-soft Camembert with nutty crackers, and crumbly Gorgonzola with honey for a sweet-salty interplay.

Understanding these textures allows for smarter pairing and storage. Soft cheeses are best consumed within 2 weeks of opening, as their high moisture makes them prone to spoilage. Semi-soft varieties can last slightly longer—up to 3 weeks—if wrapped properly. Blue cheeses, with their lower moisture and higher salt content, can endure for 4–6 weeks, though their texture will evolve from creamy to crumbly over time. Always inspect for off odors or discoloration, as mold-ripened cheeses, while intentionally moldy, should not exhibit signs of spoilage beyond their characteristic traits.

Finally, texture in mold-ripened cheeses is not just a sensory experience but a window into their craftsmanship. Each variation—soft, semi-soft, or blue-veined—reflects a unique balance of science and art, from curd handling to aging conditions. By appreciating these nuances, you can elevate your cheese board, pairing textures with wines and accompaniments that complement rather than overwhelm. For instance, a soft Brie pairs beautifully with a sparkling wine, while a robust blue like Gorgonzola stands up to a full-bodied red. Master these textures, and you’ll transform a simple cheese course into a curated tasting journey.

Mastering the Art: How to Pull String Cheese Like a Pro

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$15.99

Flavor Profiles: Earthy, nutty, tangy, or pungent, depending on mold type and aging time

Mold-ripened cheeses are a testament to the transformative power of fungi, where the interplay of mold type and aging time crafts a symphony of flavors. Among these, the earthy notes stand out as a hallmark of cheeses like Brie and Camembert. These soft-ripened cheeses develop a rich, forest-floor complexity as the white mold (Penicillium camemberti) breaks down the curd. The earthy flavor is subtle yet profound, often accompanied by a creamy texture that melts on the palate. For those seeking this profile, opt for cheeses aged 3 to 4 weeks, when the mold has fully matured but hasn’t yet turned sharp. Pair with a crusty baguette or a drizzle of honey to enhance the umami-driven earthiness.

Nutty flavors emerge in mold-ripened cheeses like aged Gouda or Mimolette, where the mold (often Penicillium candidum or other strains) interacts with the milk’s natural sugars and fats. The nuttiness intensifies with age, as the cheese hardens and develops a crystalline texture. A 12-month aged Gouda, for instance, will offer a deep, roasted almond flavor, while a younger 6-month version remains milder. To amplify this profile, serve the cheese at room temperature, allowing the fats to soften and release their aromatic compounds. Pair with a glass of caramel-forward dessert wine or a handful of toasted walnuts for a harmonious contrast.

Tanginess in mold-ripened cheeses is a delicate balance of acidity and brightness, often found in varieties like Saint-Marcellin or young Époisses. The tang comes from lactic acid development during aging, enhanced by the mold’s enzymatic activity. Younger cheeses (aged 2–3 weeks) will have a fresher, yogurt-like tang, while longer aging (4–6 weeks) deepens the flavor into something more complex and citrusy. For a tangy experience, choose cheeses with a thin rind and a soft interior, as these allow the mold to penetrate more evenly. Serve with tart fruits like green apples or cranberry compote to complement the acidity.

Pungency is the boldest expression of mold-ripened cheeses, exemplified by washed-rind varieties like Époisses or Taleggio. The pungent aroma and flavor arise from bacteria like Brevibacterium linens, which thrive alongside the mold during aging. This profile is not for the faint of heart—it’s assertive, meaty, and often described as “barnyard-like.” Aging time plays a critical role here; a 6-week aged Taleggio will be milder, while an 8-week version becomes intensely savory. To tame the pungency, pair with robust flavors like dark beer, cured meats, or pickled vegetables. For the adventurous, let the cheese sit at room temperature for 30 minutes to fully unlock its aromatic potential.

Syns in Cheese and Onion French Fries: A Diet-Friendly Guide

You may want to see also

Popular Examples: Brie, Camembert, Roquefort, Gorgonzola, and Saint-André

Mold-ripened cheeses are a testament to the artistry of fermentation, where specific molds transform humble curds into complex, flavorful masterpieces. Among these, Brie, Camembert, Roquefort, Gorgonzola, and Saint-André stand as iconic examples, each with its own distinct character and production method.

Brie and Camembert: The Creamy Cousins

Brie and Camembert share a similar production process, both originating from France and featuring a soft, bloomy rind. The white *Penicillium camemberti* mold grows on the exterior, breaking down the cheese’s interior to create a creamy, buttery texture. Brie, slightly larger and milder, pairs well with fruits and nuts, while Camembert, smaller and richer, excels when baked until molten and served with crusty bread. Both cheeses are best enjoyed at room temperature, allowing their full flavor profiles to emerge. For optimal indulgence, let them sit out for 30–60 minutes before serving.

Roquefort: The Bold Blue Veined Wonder

Roquefort, a sheep’s milk cheese from southern France, is ripened with *Penicillium roqueforti*, which creates its signature blue veins and pungent aroma. Aged in limestone caves, this cheese develops a crumbly texture and a sharp, tangy flavor. Its intensity makes it a perfect pairing for sweet accompaniments like honey or fresh figs. When using Roquefort in cooking, add it at the end to preserve its flavor—its delicate structure can break down under prolonged heat.

Gorgonzola: Italy’s Versatile Blue

Gorgonzola, Italy’s answer to blue cheese, comes in two varieties: Dolce (creamy and mild) and Piccante (firm and sharp). Both are ripened with *Penicillium glaucum*, resulting in distinctive green-blue veins. Gorgonzola Dolce is ideal for spreading on crackers or blending into pasta sauces, while Piccante shines in salads or paired with bold reds like Barolo. For a quick appetizer, crumble Gorgonzola over grilled pears and drizzle with balsamic glaze.

Saint-André: The Decadent Triple Cream

Saint-André is a triple-cream cheese, meaning it contains extra cream to achieve a rich, spreadable texture. Its bloomy rind, similar to Brie and Camembert, encases a luscious interior that melts in the mouth. This cheese is a showstopper on a cheese board, best paired with sparkling wine or a crisp white. Serve it as the finale to a meal, allowing its velvety smoothness to linger. For a luxurious twist, spread it on toasted brioche and top with a dollop of fig jam.

Each of these mold-ripened cheeses offers a unique sensory experience, from the earthy creaminess of Brie to the bold complexity of Roquefort. Understanding their nuances allows you to elevate any culinary moment, whether it’s a casual snack or an elegant dinner. Experiment with pairings, temperatures, and serving styles to unlock their full potential.

Should Cheese Babka Be Refrigerated? Storage Tips for Freshness

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Mold-ripened cheese is a type of cheese where mold is intentionally introduced to the surface, interior, or both, during the aging process. This mold contributes to the cheese's flavor, texture, and appearance.

Mold-ripened cheese is made by inoculating the cheese with specific mold cultures, either by spraying the surface, mixing it into the curd, or allowing it to develop naturally during aging. The mold then grows and transforms the cheese as it matures.

Examples of mold-ripened cheeses include Brie, Camembert, Blue Cheese (like Roquefort or Gorgonzola), and Saint-André. These cheeses vary in texture, from soft and creamy to semi-soft with veins of mold.

Yes, mold-ripened cheese is safe to eat when properly made and stored. The molds used in these cheeses are carefully selected and controlled, unlike harmful molds that can grow on spoiled food. Always check for freshness and proper storage conditions.