Ammonia levels in different cheeses vary significantly depending on factors such as cheese type, aging process, and bacterial activity during fermentation. Soft cheeses like Brie and Camembert tend to have higher ammonia levels due to the presence of specific bacteria that produce ammonia as a byproduct of protein breakdown. In contrast, harder cheeses like Cheddar and Parmesan generally exhibit lower ammonia levels, as their longer aging processes allow for more ammonia to dissipate. Blue cheeses, such as Roquefort and Gorgonzola, often contain moderate to high ammonia levels due to the unique mold cultures involved in their production. Understanding these variations is crucial for both cheese makers and consumers, as ammonia levels can influence flavor profiles, texture, and overall quality of the cheese.

Explore related products

$12.46

What You'll Learn

- Fresh vs. Aged Cheeses: Compare ammonia levels in fresh cheeses like mozzarella versus aged ones like Parmesan

- Cheese Ripening Process: How ammonia levels increase during the ripening and aging of cheeses

- Cheese Types and Ammonia: Ammonia variations in soft, semi-hard, and hard cheeses (e.g., Brie, Cheddar)

- Ammonia in Blue Cheeses: Unique ammonia levels in blue cheeses due to specific bacterial cultures

- Measurement Techniques: Methods used to measure ammonia levels in different cheese varieties

Fresh vs. Aged Cheeses: Compare ammonia levels in fresh cheeses like mozzarella versus aged ones like Parmesan

Ammonia levels in cheese are a byproduct of protein breakdown during aging, serving as a key indicator of ripeness and flavor intensity. Fresh cheeses like mozzarella, typically aged for less than a month, contain minimal ammonia—usually below 5 parts per million (ppm). This low level contributes to their mild, milky taste and soft texture. In contrast, aged cheeses such as Parmesan, matured for over a year, can have ammonia levels exceeding 50 ppm. This higher concentration is responsible for their sharp, nutty flavors and harder textures. Understanding this difference helps explain why fresh and aged cheeses serve distinct culinary purposes.

To compare, consider the aging process as a controlled transformation. Fresh cheeses undergo little enzymatic activity, preserving their natural lactose and proteins with minimal ammonia production. Mozzarella, for instance, is often consumed within days of production, ensuring its delicate profile remains intact. Aged cheeses, however, experience prolonged microbial activity, breaking down proteins into amino acids and ammonia. Parmesan’s extended aging allows ammonia to accumulate, creating its signature complexity. This contrast highlights how time and microbiology dictate not only flavor but also ammonia content.

Practical implications arise when pairing or cooking with these cheeses. Fresh cheeses like mozzarella are ideal for dishes where subtlety is desired, such as caprese salads or pizza, where their low ammonia levels avoid overpowering other ingredients. Aged cheeses like Parmesan, with their higher ammonia content, excel in applications requiring boldness—grated over pasta or risotto, where their umami-rich profile enhances the dish. Chefs and home cooks alike can leverage this knowledge to balance flavors effectively, ensuring each cheese’s unique characteristics shine.

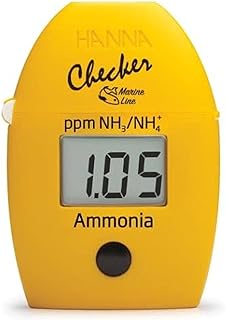

For those curious about measuring ammonia levels, home testing kits are available, though they’re more commonly used in professional settings. Commercially, cheese producers monitor ammonia during aging to ensure quality and consistency. While precise values vary by brand and batch, the general trend remains: fresher cheeses stay low in ammonia, while aged varieties climb significantly. This distinction not only informs culinary choices but also deepens appreciation for the science behind cheese craftsmanship.

In summary, the ammonia levels in fresh versus aged cheeses reflect their distinct aging processes and sensory profiles. Mozzarella’s minimal ammonia aligns with its freshness and versatility, while Parmesan’s higher levels embody its depth and longevity. By recognizing this relationship, consumers can make informed decisions, whether selecting the right cheese for a recipe or simply savoring its unique qualities. The next time you enjoy a slice of mozzarella or grate Parmesan, remember: ammonia is the silent architect shaping their flavors.

Decoding Drake's 'Cheese': Unraveling the Meaning Behind the Lyrics

You may want to see also

Cheese Ripening Process: How ammonia levels increase during the ripening and aging of cheeses

Ammonia levels in cheese are a critical indicator of the ripening process, reflecting the breakdown of proteins into simpler compounds. During aging, bacteria and enzymes act on the cheese’s protein matrix, releasing ammonia as a byproduct. This process is particularly pronounced in aged cheeses, where ammonia contributes to flavor complexity and texture development. For instance, hard cheeses like Parmesan or Gruyère exhibit higher ammonia levels compared to fresh cheeses like mozzarella or ricotta, which undergo minimal aging. Understanding this relationship is key to appreciating how ammonia shapes the sensory profile of different cheeses.

The ripening process begins with the curd formation, where proteins are initially intact. As aging progresses, proteolytic enzymes and bacteria, such as *Lactobacillus* and *Propionibacterium*, break down casein proteins into peptides and free amino acids. These amino acids are further metabolized, releasing ammonia (NH₃) as a waste product. In young cheeses, ammonia levels are negligible, typically below 10 ppm. However, in aged cheeses, levels can rise to 100–300 ppm or higher, depending on the cheese variety and aging conditions. For example, blue cheeses like Roquefort or Stilton often have elevated ammonia levels due to the activity of *Penicillium* molds, which accelerate protein breakdown.

Controlling ammonia levels during ripening is both an art and a science. Factors such as temperature, humidity, and salt content influence bacterial activity and enzyme function. Higher temperatures (12–15°C) and optimal moisture levels (40–50% relative humidity) promote faster protein degradation, increasing ammonia production. Cheesemakers often adjust these parameters to achieve desired flavor profiles. For instance, a cheddar aged for 12 months at 8°C will have lower ammonia levels than one aged for 24 months at 12°C. Practical tips include monitoring pH levels, as ammonia accumulation can raise pH, affecting texture and flavor. Regular sampling and testing can help cheesemakers fine-tune aging conditions to balance ammonia levels with other sensory attributes.

Comparatively, ammonia’s role in cheese ripening differs across varieties. In semi-soft cheeses like Emmental, ammonia contributes to the characteristic nutty flavor and open texture, while in washed-rind cheeses like Époisses, it adds pungency. However, excessive ammonia can lead to off-flavors, such as bitterness or a "barnyard" aroma. Cheesemakers must strike a balance, often using starter cultures with specific metabolic profiles to control ammonia production. For home cheesemakers, aging cheeses in a controlled environment, such as a wine fridge set to 10–13°C, can help manage ammonia levels effectively.

In conclusion, ammonia levels are a dynamic aspect of the cheese ripening process, influenced by microbial activity, aging conditions, and cheese type. While essential for developing flavor and texture, excessive ammonia can detract from the final product. By understanding the mechanisms behind ammonia production and employing precise aging techniques, cheesemakers can craft cheeses with optimal sensory qualities. Whether producing a mild cheddar or a bold blue cheese, mastering ammonia levels is a cornerstone of the cheesemaking craft.

Should You Remove the Skin from Brie Cheese? A Tasty Debate

You may want to see also

Cheese Types and Ammonia: Ammonia variations in soft, semi-hard, and hard cheeses (e.g., Brie, Cheddar)

Ammonia levels in cheese are a byproduct of protein breakdown during ripening, influenced by factors like moisture content, aging time, and bacterial activity. Soft cheeses like Brie, with higher moisture and shorter aging, exhibit lower ammonia levels, typically around 5-10 ppm. This mild presence contributes to their subtle, earthy flavors without overpowering the palate. In contrast, semi-hard cheeses such as Cheddar, aged longer and with reduced moisture, show moderate ammonia levels, ranging from 15 to 30 ppm. This increase enhances their sharper, tangier profiles, characteristic of well-aged varieties. Hard cheeses, like Parmesan, aged extensively and with minimal moisture, can reach ammonia levels of 40 ppm or higher, adding complexity to their robust, nutty flavors. Understanding these variations helps cheese enthusiasts appreciate how texture and aging processes shape both taste and chemical composition.

To illustrate, consider the ripening process of Brie versus Cheddar. Brie’s high moisture environment fosters lactic acid bacteria that produce minimal ammonia, preserving its creamy texture and delicate aroma. Cheddar, aged for months in drier conditions, allows proteolytic bacteria to break down proteins more extensively, elevating ammonia levels and intensifying its flavor. For home cheesemakers, controlling moisture and aging time is key to managing ammonia production. Soft cheeses should be aged for 2-4 weeks in high-humidity environments, while semi-hard varieties benefit from 3-6 months in moderate humidity. Hard cheeses require 1-2 years in low-humidity conditions to develop their signature ammonia-rich profiles. Monitoring these parameters ensures the desired balance of flavor and texture.

From a health perspective, ammonia levels in cheese are generally safe for consumption, as they remain within regulatory limits. However, individuals with sensitivities to strong flavors or those on low-protein diets may prefer softer cheeses with lower ammonia content. Pairing cheeses strategically can also mitigate perceived intensity—for instance, serving sharp Cheddar with sweet fruits or nuts balances its tanginess. For culinary experimentation, understanding ammonia variations allows chefs to create harmonious cheese boards or recipes. A soft Brie paired with a hard Parmesan showcases the spectrum of flavors, from mild to bold, offering a sensory journey through cheese craftsmanship.

Comparatively, the ammonia profile of a cheese reflects its microbial ecosystem and aging conditions. Soft-ripened cheeses like Camembert rely on surface molds that limit protein breakdown, keeping ammonia levels low. Semi-hard cheeses like Gouda or Swiss undergo partial moisture loss, allowing moderate ammonia accumulation. Hard cheeses like Pecorino or Grana Padano, aged in dry environments, maximize protein degradation, resulting in higher ammonia concentrations. This progression highlights how cheese categories are not just textural distinctions but chemical narratives shaped by time and technique. By studying these trends, consumers can make informed choices, whether seeking mild accompaniments or bold centerpieces for their culinary creations.

Cheese Making Process: Does Water Remain After Curdling Milk?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Ammonia in Blue Cheeses: Unique ammonia levels in blue cheeses due to specific bacterial cultures

Blue cheeses, such as Roquefort, Gorgonzola, and Stilton, are renowned for their distinctive pungent aroma and sharp flavor, which are largely attributed to elevated ammonia levels. These levels are significantly higher than those found in other cheese varieties, often ranging between 10 to 50 parts per million (ppm), compared to 1 to 5 ppm in milder cheeses like cheddar or mozzarella. This unique characteristic is not accidental but a direct result of the specific bacterial cultures involved in their production, particularly *Penicillium roqueforti*, which metabolizes proteins into ammonia as part of its ripening process. Understanding this process is key to appreciating why blue cheeses stand apart in the world of dairy.

The role of *Penicillium roqueforti* in blue cheese production cannot be overstated. Unlike bacteria in other cheeses, this mold species produces proteases that break down milk proteins into amino acids, which are further converted into ammonia. This metabolic activity is most pronounced during the aging process, typically lasting 2 to 6 months, depending on the variety. For instance, Roquefort, aged for a minimum of 90 days, often exhibits higher ammonia levels due to its longer maturation period. Producers carefully control temperature and humidity to optimize mold growth, ensuring the desired ammonia profile without overwhelming the cheese’s other sensory qualities.

From a sensory perspective, ammonia in blue cheeses serves a dual purpose. At moderate levels, it enhances the cheese’s complexity, contributing to its characteristic tanginess and depth of flavor. However, excessive ammonia can lead to an unpleasant, sharp taste and a burning sensation in the nose. Master cheesemakers balance this fine line by monitoring pH levels and adjusting aging conditions. For example, a pH range of 6.5 to 7.0 is ideal for *Penicillium roqueforti* activity, fostering ammonia production without compromising texture or aroma. This precision underscores the art and science behind crafting blue cheeses.

For consumers, understanding ammonia levels in blue cheeses can enhance appreciation and pairing choices. Mild blue cheeses, such as Danish Blue, with lower ammonia levels (around 10 ppm), pair well with sweet accompaniments like honey or fruit, as their subtler flavors are not overshadowed. In contrast, bold varieties like Roquefort, with ammonia levels closer to 50 ppm, stand up to robust wines or dark chocolate, their intensity complementing equally strong flavors. When serving blue cheese, allow it to come to room temperature to fully release its aromatic compounds, including ammonia, for a more nuanced tasting experience.

In conclusion, the unique ammonia levels in blue cheeses are a testament to the interplay between specific bacterial cultures and meticulous production techniques. From the proteolytic activity of *Penicillium roqueforti* to the careful control of aging conditions, every step contributes to the cheese’s signature profile. Whether you’re a producer refining your craft or a consumer exploring new flavors, recognizing the role of ammonia in blue cheeses offers deeper insight into what makes these varieties truly exceptional.

Round Cheese Blocks: Uncovering the Surprising Names Behind Circular Cheeses

You may want to see also

Measurement Techniques: Methods used to measure ammonia levels in different cheese varieties

Ammonia levels in cheese are a critical indicator of ripening, spoilage, and sensory quality, but measuring them accurately requires precise techniques tailored to the cheese variety. One widely adopted method is gas chromatography (GC), which separates and quantifies ammonia in cheese extracts with high sensitivity. For instance, in a study on Cheddar and Camembert, GC detected ammonia levels ranging from 50 to 300 ppm, depending on ripening duration. This method is ideal for aged cheeses where ammonia accumulates over time, but it demands specialized equipment and expertise.

For on-site or rapid assessments, ammonia electrode sensors offer a practical alternative. These sensors measure ammonia in cheese extracts by detecting changes in pH, providing results within minutes. A key advantage is their portability, making them suitable for small-scale producers. However, calibration is critical, as factors like temperature and cheese matrix complexity can skew readings. For example, in fresh cheeses like mozzarella, where ammonia levels are typically below 20 ppm, precise calibration ensures accurate detection of even trace amounts.

Another technique, spectrophotometry, uses colorimetric reactions to quantify ammonia. The Nessler reagent, which reacts with ammonia to form a yellow-brown complex, is commonly employed. This method is cost-effective and accessible, but it may lack the sensitivity needed for low-ammonia cheeses like fresh ricotta. For instance, in a study on blue cheeses, spectrophotometry measured ammonia levels up to 1,000 ppm, highlighting its utility in highly ripened varieties. However, interference from other cheese components can reduce accuracy, requiring careful sample preparation.

Lastly, headspace analysis is a non-destructive method that measures volatile ammonia directly from the cheese surface. This technique is particularly useful for monitoring surface-ripened cheeses like Brie, where ammonia levels can exceed 500 ppm. By trapping and analyzing gases released during ripening, headspace analysis provides real-time data without altering the cheese. However, it may not capture ammonia distributed within the cheese matrix, making it a complementary rather than standalone method.

In practice, the choice of measurement technique depends on the cheese variety, ripening stage, and available resources. For aged, high-ammonia cheeses, GC or spectrophotometry offers precision, while rapid sensors are ideal for fresh cheeses or on-site monitoring. Combining methods, such as using headspace analysis alongside GC, can provide a comprehensive understanding of ammonia distribution and dynamics. Regardless of the technique, consistent sampling and standardized protocols are essential to ensure reliable results across different cheese varieties.

American Cheese Calcium Content: How Much Does It Really Provide?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Hard cheeses such as Cheddar and Parmesan generally have low ammonia levels, typically ranging from 1 to 5 parts per million (ppm). The aging process in these cheeses reduces moisture content, limiting bacterial activity that produces ammonia.

Yes, soft cheeses like Brie and Camembert often have higher ammonia levels, ranging from 10 to 30 ppm. Their higher moisture content and shorter aging time allow for more bacterial activity, leading to increased ammonia production.

Blue cheeses such as Gorgonzola and Roquefort can have significantly higher ammonia levels, often ranging from 50 to 150 ppm. The presence of Penicillium mold and specific ripening conditions contribute to elevated ammonia production in these cheeses.

![Ammonia Test Strips 0-100 ppm [Vial of 25 Strips] for Industrial Applications](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/61-eQd3b1vL._AC_UL320_.jpg)

![Refrigerant Test Strip for Ammonia Gas Leak Detection [Vial of 100 Paper Strips]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/61vYdcnwNJL._AC_UL320_.jpg)

![Ammonia NH3 Test Strips, 0-6ppm for Aquarium, Fish Tank and Pond Monitoring [Vial of 25]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/71AdAWl0YZL._AC_UL320_.jpg)