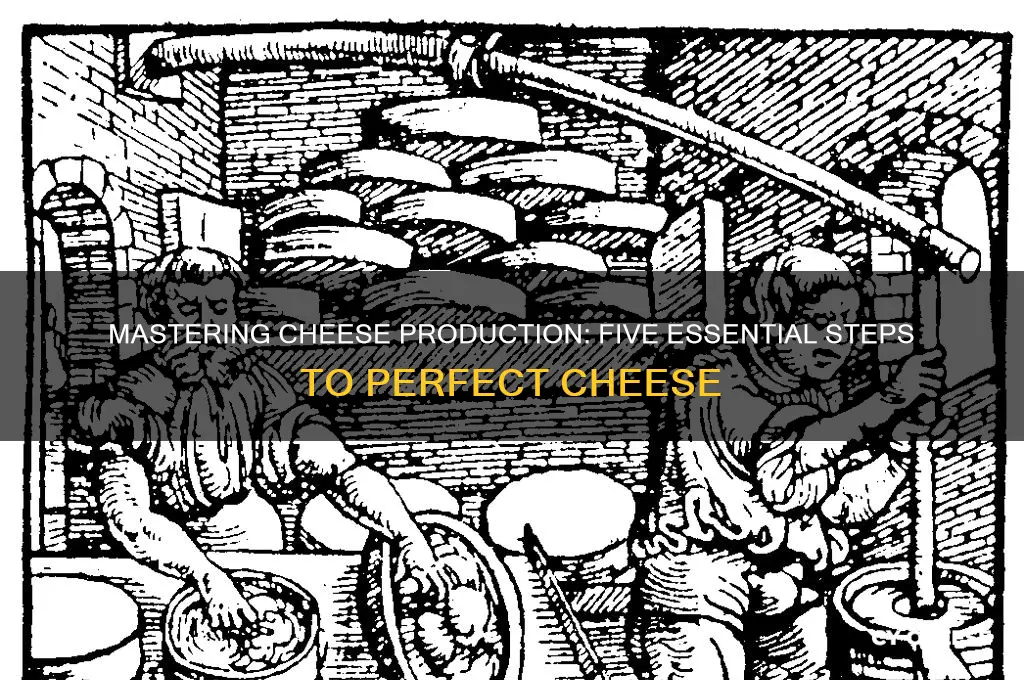

Cheese production is a fascinating process that transforms milk into a diverse array of flavors, textures, and styles. The journey from milk to cheese involves five key steps: milk preparation, where the milk is selected, pasteurized, or left raw, and often acidified; coagulation, where enzymes or acids are added to curdle the milk, separating it into curds and whey; draining and pressing, where excess whey is removed, and the curds are shaped and pressed to achieve the desired texture; salting, which enhances flavor and preserves the cheese; and ripening or aging, where the cheese is stored under controlled conditions to develop its unique characteristics through microbial activity and enzymatic processes. Each step is crucial in crafting the final product, making cheese production both a science and an art.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| 1. Milk Preparation | Raw or pasteurized milk is selected based on desired cheese type. Acidification with starter cultures (bacteria) begins, lowering pH and creating lactic acid, essential for flavor and texture development. |

| 2. Coagulation | Rennet or other coagulating agents are added to solidify the milk into curds (solid) and whey (liquid). This step determines the cheese's texture and structure. |

| 3. Draining and Cutting | The curds are cut into smaller pieces to release more whey. The size of the cuts influences the final cheese's moisture content and texture. |

| 4. Salting and Pressing | Salt is added to the curds for flavor and preservation. The curds are then pressed to remove more whey and form a cohesive mass. Pressure and duration vary depending on the cheese type. |

| 5. Ripening/Aging | The cheese is stored under controlled temperature and humidity conditions for a specific period. During this time, bacteria and molds continue to develop flavor, texture, and aroma. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Milk Selection: Choosing high-quality milk, often cow, goat, or sheep, as the base for cheese

- Coagulation Process: Adding rennet or acid to curdle milk, separating curds from whey

- Curd Handling: Cutting, stirring, and heating curds to release moisture and develop texture

- Salting and Pressing: Adding salt to preserve cheese, then pressing to remove excess whey

- Aging and Ripening: Storing cheese in controlled conditions to develop flavor and texture

Milk Selection: Choosing high-quality milk, often cow, goat, or sheep, as the base for cheese

The foundation of exceptional cheese lies in the quality of its primary ingredient: milk. Milk selection is a critical step in cheese production, as it directly influences the flavor, texture, and overall character of the final product. Whether sourced from cows, goats, or sheep, the milk must meet stringent standards to ensure the cheese’s success. For instance, cow’s milk, the most commonly used base, is prized for its versatility and balanced fat content, typically ranging from 3.5% to 4.0% in whole milk. Goat’s milk, with its naturally lower fat content (around 3.5%) and distinct tang, is ideal for cheeses like chèvre or feta. Sheep’s milk, richer in fat (6% to 8%) and solids, produces robust, creamy cheeses such as Manchego or Pecorino. Each type of milk imparts unique qualities, making the choice a defining factor in the cheese’s identity.

Selecting high-quality milk involves more than just choosing the animal source. Producers must consider factors like the animal’s diet, health, and living conditions, as these elements significantly affect milk composition. For example, grass-fed cows produce milk with higher levels of conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) and omega-3 fatty acids, contributing to richer flavors and potential health benefits. Similarly, seasonal variations in grazing can alter milk’s fat and protein content, requiring adjustments in cheese-making techniques. Pasteurization vs. raw milk is another critical decision. While pasteurized milk ensures safety and consistency, raw milk is favored by artisanal cheesemakers for its complex microbial profile, which can enhance flavor development during aging.

Practical tips for milk selection include testing for acidity (pH levels should ideally be between 6.6 and 6.8) and ensuring the milk is free from antibiotics or additives that could interfere with coagulation. Temperature control is also vital; milk should be stored at 4°C (39°F) to preserve freshness before processing. For small-scale producers, sourcing milk from local, trusted farms can provide greater control over quality. Larger operations may rely on standardized milk supplies, but even then, rigorous testing for fat, protein, and somatic cell counts is essential to maintain consistency.

The choice of milk is not just a technical decision but an artistic one, shaping the cheese’s personality. A master cheesemaker might opt for sheep’s milk to create a dense, nutty cheese or goat’s milk for a light, tangy variety. Understanding the interplay between milk type, animal care, and processing techniques allows producers to craft cheeses that stand out in flavor and texture. Ultimately, milk selection is where the journey of cheese begins, setting the stage for every step that follows.

Sharp vs. Extra Sharp Cheese: Unraveling the Texture Differences

You may want to see also

Coagulation Process: Adding rennet or acid to curdle milk, separating curds from whey

The coagulation process is a pivotal moment in cheese production, transforming liquid milk into a solid foundation for cheese. This step involves adding a coagulant—either rennet or acid—to milk, causing it to curdle and separate into curds (the solid part) and whey (the liquid part). The choice of coagulant and its application significantly influence the texture, flavor, and overall character of the final cheese. For instance, rennet, derived from the stomach lining of ruminant animals, produces a firmer curd ideal for hard cheeses like Cheddar, while acid coagulants like vinegar or citric acid yield softer curds suited for fresh cheeses like ricotta.

When using rennet, precision is key. Typically, 1/4 to 1/2 teaspoon of liquid rennet diluted in 1/4 cup of cool, non-chlorinated water is added per gallon of milk. The milk should be heated to around 86–100°F (30–38°C), depending on the cheese type, before adding the rennet mixture. Stir gently for about 1 minute to ensure even distribution, then let the milk rest undisturbed for 10–60 minutes until a clean break is achieved—a clear separation between curds and whey when the mixture is cut with a knife. Over-stirring or using too much rennet can result in a tough, rubbery curd, while under-stirring or insufficient rennet may prevent proper coagulation.

Acid coagulation, on the other hand, is simpler and faster, making it popular for home cheesemaking. For ricotta, heat milk to 180–195°F (82–90°C), then add 2–3 tablespoons of white vinegar or lemon juice per gallon of milk. Stir gently for 10–20 seconds, and within minutes, the curds will form and rise to the surface. This method is less precise than rennet coagulation but offers immediate results. However, acid-coagulated cheeses tend to have a tangier flavor and softer texture, limiting their versatility in aging or melting applications.

The separation of curds from whey is a critical step in both methods. After coagulation, the curds are cut into smaller pieces to release more whey, a process that affects moisture content and final texture. For hard cheeses, the curds are heated and stirred to expel additional whey, while soft cheeses retain more moisture. The whey, rich in protein and lactose, can be saved for animal feed, fermentation, or even as a base for whey cheese like ricotta. Proper handling during this stage ensures the curds remain intact and free from bitterness, setting the stage for the next steps in cheese production.

In summary, the coagulation process is both an art and a science, requiring careful attention to coagulant type, dosage, and technique. Whether using rennet for a firm, aged cheese or acid for a fresh, soft variety, mastering this step is essential for achieving the desired outcome. By understanding the nuances of coagulation, cheesemakers can control the fundamental structure of their cheese, paving the way for successful aging, flavor development, and final presentation.

DIY Distressed Denim: Rip Jeans with a Cheese Grater Guide

You may want to see also

Curd Handling: Cutting, stirring, and heating curds to release moisture and develop texture

Curd handling is a delicate dance of precision and timing, where the transformation from milky curds to textured cheese begins. This critical phase involves cutting, stirring, and heating the curds to release whey and develop the desired texture. Each action must be executed with care, as the curds are fragile and can easily break or become too tough. The goal is to create a uniform structure while expelling moisture, setting the foundation for the cheese’s final consistency.

Cutting the curd is the first step, and it’s both an art and a science. The curd is sliced into uniform pieces using a tool called a cheese harp or knife. The size of the cut determines how quickly whey is released and influences the cheese’s texture. For example, smaller cuts (about 1–2 cm) are used for hard cheeses like cheddar, allowing more whey to drain and creating a denser curd. Larger cuts (2–3 cm) are typical for softer cheeses like mozzarella, retaining more moisture for a pliable texture. The curd’s firmness at this stage is crucial; it should be soft enough to cut easily but not so soft that it crumbles.

Stirring follows cutting and serves multiple purposes. It prevents the curds from matting together, ensures even heat distribution, and encourages further whey expulsion. The technique varies by cheese type: gentle stirring is used for soft cheeses to avoid breaking the curds, while more vigorous stirring is applied to hard cheeses to firm them up. Temperature control during stirring is critical. For cheddar, the curds are stirred at 37–40°C (98–104°F) for 20–30 minutes, gradually increasing to 46°C (115°F) to expel more whey and tighten the texture. Overstirring or overheating can lead to a rubbery or grainy final product, so constant monitoring is essential.

Heating the curds is the final step in curd handling and is pivotal in developing texture. The curds are cooked in their own whey, with the temperature and duration tailored to the cheese variety. For semi-hard cheeses like Gruyère, the curds are heated to 50–55°C (122–131°F) for 30–45 minutes, creating a smooth, elastic texture. In contrast, fresh cheeses like ricotta are minimally heated to preserve their delicate crumbly nature. A practical tip: use a thermometer to monitor the temperature, as even a 1–2°C deviation can significantly impact the outcome.

Mastering curd handling requires practice and attention to detail. Each cheese type demands specific techniques, but the underlying principles remain consistent: control moisture, develop texture, and preserve curd integrity. By understanding the interplay of cutting, stirring, and heating, cheesemakers can craft products with the desired consistency, from creamy bries to crumbly fetas. This phase is where the cheese’s character begins to emerge, making it a cornerstone of the production process.

Cleaning Cheesecloth for Kombucha: Warm Water Tips and Tricks

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Salting and Pressing: Adding salt to preserve cheese, then pressing to remove excess whey

Salt is the silent guardian of cheese, a mineral that transforms a perishable curd into a stable, flavorful foundation. In the salting stage, cheese makers introduce salt to the curds, either by directly mixing it in or brining the cheese. The salt acts as a preservative, inhibiting bacterial growth and slowing the aging process. For semi-hard cheeses like cheddar, a salt concentration of 1.5-2% of the curd weight is typical, added gradually to ensure even distribution. This step is crucial; too little salt can lead to spoilage, while too much can overpower the cheese’s natural flavors.

Pressing follows salting, a mechanical process that expels excess whey and consolidates the curds into a denser form. The pressure applied depends on the cheese type—softer cheeses like mozzarella require minimal pressing, while hard cheeses like Parmesan endure hours under heavy weights. Pressing not only shapes the cheese but also influences its texture and moisture content. For instance, a cheddar might be pressed at 30-50 pounds of pressure for several hours, resulting in a firm yet sliceable consistency. Without proper pressing, the cheese would retain too much whey, leading to a crumbly, uneven structure.

The interplay between salting and pressing is a delicate balance. Salt draws out moisture through osmosis, making the curds firmer and easier to press. However, pressing too soon after salting can cause uneven salt distribution, as the curds haven’t had time to absorb it fully. Cheese makers often wait 12-24 hours after salting before pressing, allowing the salt to penetrate the curds evenly. This patience ensures the cheese develops a consistent flavor and texture, hallmarks of quality craftsmanship.

Practical tips for home cheese makers: Use non-iodized salt, as iodine can affect flavor and color. Apply pressure gradually, starting light and increasing over time to avoid cracking the curd. For small-scale production, a simple press made from weighted boards or even heavy books can suffice. Monitor the cheese’s moisture release during pressing; it should expel whey steadily without becoming dry. Mastering salting and pressing elevates cheese from a basic curd to a preserved, textured delight, ready for aging or immediate enjoyment.

Borrowed Brie: The Humor in Naming Others' Cheesy Possessions

You may want to see also

Aging and Ripening: Storing cheese in controlled conditions to develop flavor and texture

The aging and ripening process is where cheese transforms from a simple curd into a complex, flavorful masterpiece. This stage is an art as much as a science, requiring precise control of temperature, humidity, and time to unlock the desired taste and texture. Imagine a young, mild cheese evolving into a sharp, crumbly cheddar or a creamy, pungent Camembert—all through the magic of aging.

The Science Behind the Flavor: During aging, the cheese's internal environment becomes a bustling hub of microbial activity. Bacteria and molds, either naturally present or added during production, break down proteins and fats, releasing a myriad of compounds that contribute to flavor and aroma. For instance, the breakdown of proteins creates amino acids, which can impart nutty, brothy, or savory notes. Similarly, the transformation of fats can lead to the development of fruity, spicy, or even buttery flavors. This biological process is highly sensitive to environmental conditions, making controlled storage critical.

Creating the Perfect Environment: Cheese aging requires a carefully managed atmosphere. Temperature and humidity are the key players. Most cheeses age between 50–55°F (10–13°C), with humidity levels around 85–95%. These conditions encourage the desired microbial activity while preventing excessive drying or mold growth. For example, a higher humidity is essential for soft-ripened cheeses like Brie to develop their characteristic bloomy rind and creamy interior. In contrast, harder cheeses like Parmesan benefit from lower humidity to promote moisture loss and concentrate flavors.

Time, the Master Craftsman: Aging duration varies widely, from a few weeks to several years, depending on the cheese variety and desired characteristics. Young cheeses, aged for a short period, tend to be milder and more moist, while older cheeses become firmer, sharper, and more complex. For instance, a young Gouda might be aged for 4–6 weeks, resulting in a sweet, creamy cheese, whereas an aged Gouda could spend 6–12 months in storage, developing a harder texture and caramelized, nutty flavors. This transformation is a testament to the power of time in crafting cheese's unique personalities.

Practical Tips for Home Aging: For enthusiasts looking to age cheese at home, consistency is key. Invest in a dedicated cheese aging fridge or a wine fridge, which can maintain stable temperatures and humidity levels. Regularly monitor and adjust these conditions, especially humidity, as it can fluctuate with the cheese's moisture content. Additionally, proper wrapping is essential. Use cheese paper or breathable wrap to allow gases to escape while retaining moisture. Finally, be patient and trust the process—aging is a slow dance, and rushing it may compromise the final product's quality.

In the world of cheese production, aging and ripening are the steps that truly differentiate one cheese from another. It is during this phase that the cheese's unique character emerges, offering a sensory experience that can transport you from a creamy, mild dream to a sharp, pungent adventure. Understanding and controlling these variables allow cheesemakers to craft an extraordinary diversity of flavors and textures, ensuring there's a cheese for every palate.

Baking Camembert in a Box: A Simple, Cheesy Delight

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The first step is milk preparation, where raw milk is tested, standardized, and pasteurized (if necessary) to ensure quality and safety.

During coagulation, rennet or acid is added to the milk to curdle it, separating it into solid curds (milk solids) and liquid whey.

Cutting and stirring the curds releases whey and helps control the texture and moisture content of the final cheese.

The final step is ripening or aging, where the cheese is stored under controlled conditions to develop flavor, texture, and aroma.