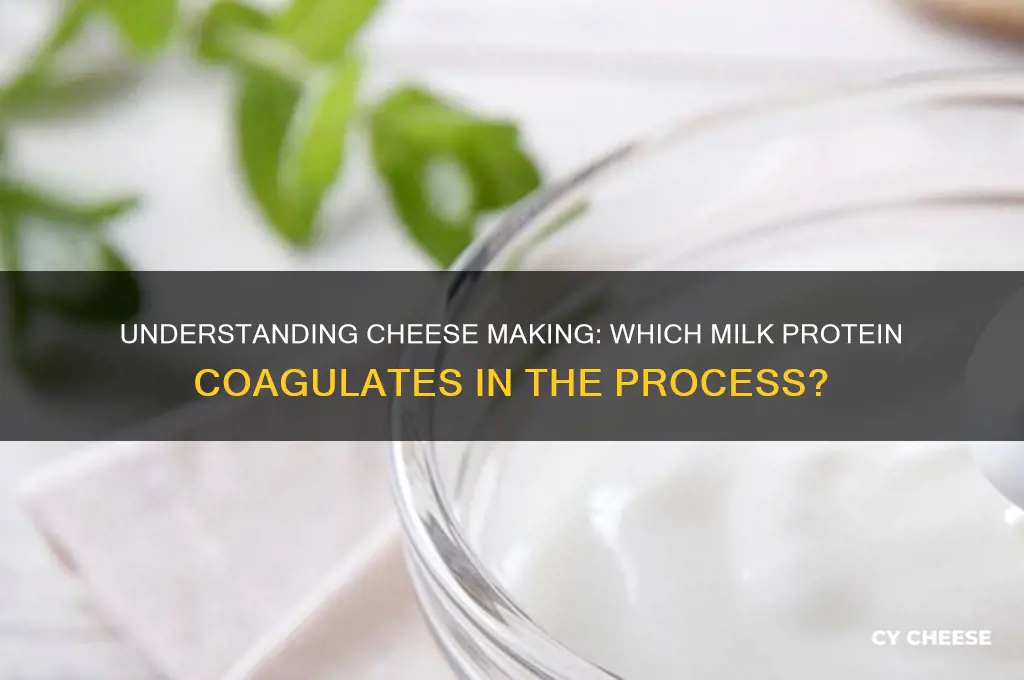

Cheese making is a complex process that involves the coagulation of milk proteins, primarily casein, which constitutes about 80% of the total protein content in milk. During cheese production, enzymes like rennet or acids are added to milk, causing the casein proteins to aggregate and form a solid mass known as the curd, while the liquid whey is separated. This coagulation step is crucial, as it determines the texture, structure, and overall quality of the final cheese product. Understanding the specific category of milk protein involved in this process—casein—sheds light on the science behind cheese making and highlights its role in transforming liquid milk into a diverse array of cheeses.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Rennet Enzymes: Role in cleaving κ-casein, initiating coagulation of milk proteins during cheese production

- Curd Formation: Process where casein proteins aggregate, separating into solid curds and liquid whey

- Casein Types: αs1, αs2, β, κ caseins and their specific roles in coagulation

- Acid Coagulation: Use of acids like lactic acid to coagulate milk in some cheeses

- Heat Treatment: Effect of temperature on protein denaturation and coagulation in cheese making

Rennet Enzymes: Role in cleaving κ-casein, initiating coagulation of milk proteins during cheese production

Cheese making hinges on the coagulation of milk proteins, primarily caseins, which constitute about 80% of milk’s protein content. Among these, κ-casein plays a pivotal role in stabilizing the milk micelle, preventing spontaneous clotting. Rennet enzymes, derived from animal sources or microbial cultures, are the catalysts that cleave κ-casein, destabilizing the micelle and initiating coagulation. This precise enzymatic action is the linchpin of cheese production, transforming liquid milk into a solid curd.

Analytically, the process begins with the addition of rennet, typically at a dosage of 0.02–0.05% (v/v) for traditional cheese making. The active enzyme in rennet, chymosin, targets a specific peptide bond in κ-casein, cleaving it into two fragments: para-κ-casein and macropeptide. This cleavage removes the hydrophilic macropeptide, leaving behind para-κ-casein, which is hydrophobic. The loss of the stabilizing macropeptide causes the casein micelles to aggregate, forming a gel-like structure—the curd. This reaction is highly pH-dependent, optimal at pH 6.0–6.6, and temperature-sensitive, typically performed at 30–35°C for most cheeses.

Instructively, for home cheese makers, understanding rennet’s role is crucial for achieving consistent results. Always dilute liquid rennet in cool, non-chlorinated water before adding it to milk to ensure even distribution. Stir gently for 1–2 minutes, then let the milk rest undisturbed for 30–60 minutes, depending on the recipe. Overuse of rennet can lead to a bitter taste and excessively firm curd, while underuse results in a weak, slow-forming curd. For vegetarian alternatives, microbial rennet or fermentation-produced chymosin (FPC) can be used, offering similar efficacy without animal-derived components.

Persuasively, the precision of rennet’s action on κ-casein underscores its indispensability in cheese making. While acid coagulation (e.g., using vinegar or lemon juice) can also curdle milk, it lacks the control and texture refinement achieved with rennet. Rennet-induced coagulation produces a cleaner break between curds and whey, essential for aged and hard cheeses. Moreover, the enzymatic process preserves milk’s natural flavor profile, allowing the cheese’s character to develop fully during aging. This is why artisanal and industrial cheese makers alike rely on rennet as their primary coagulant.

Comparatively, the role of rennet in cleaving κ-casein contrasts with the mechanisms of other milk-clotting agents. For instance, microbial transglutaminase, used in some modern cheese making, cross-links proteins rather than cleaving them, resulting in a different curd structure. Similarly, plant-based coagulants like fig tree bark extract act less specifically, often leading to a softer, less defined curd. Rennet’s specificity and efficiency make it the gold standard, particularly for traditional and premium cheeses where texture and flavor are paramount.

Descriptively, the transformation of milk into cheese through rennet’s action on κ-casein is a marvel of biochemistry. Imagine milk, a fluid suspension of fats, proteins, and sugars, metamorphosing into a solid mass as rennet’s enzymes work their magic. The curd, once formed, is a testament to the delicate balance of science and art in cheese making. From this point, the curd is cut, heated, and pressed, eventually maturing into the diverse array of cheeses we know and love. Rennet’s role in this process is not just functional but foundational, a silent hero in every wheel, wedge, and slice.

Can You Eat Cheese on Keto? A Diet-Friendly Guide

You may want to see also

Curd Formation: Process where casein proteins aggregate, separating into solid curds and liquid whey

Milk contains a complex mixture of proteins, but during cheese making, it’s the casein proteins that take center stage. These proteins, which make up about 80% of milk’s protein content, are the primary drivers of curd formation. When casein proteins aggregate, they transform from a dispersed state in milk into a solid mass, separating from the liquid whey. This process is not just a random clumping; it’s a precise, enzyme-driven reaction that forms the foundation of cheese production. Understanding this mechanism is crucial for anyone looking to master the art of cheese making or troubleshoot common issues in the process.

The aggregation of casein proteins begins with the addition of rennet or other coagulating agents. Rennet, a complex of enzymes, specifically targets kappa-casein, a component of the casein micelle. By cleaving kappa-casein, rennet destabilizes the micelle structure, allowing calcium ions to bridge the now-exposed casein molecules. This bridging creates a network of protein chains, forming a gel-like matrix. The strength and speed of this reaction depend on factors like milk pH, temperature, and the type of coagulant used. For example, a pH of 6.5–6.6 is ideal for most cheeses, as it ensures optimal enzyme activity without prematurely destabilizing the micelles.

Once the casein network forms, the curd begins to shrink, expelling whey. This step, known as syneresis, is critical for achieving the desired texture and moisture content in the final cheese. The rate of syneresis can be controlled by adjusting cutting techniques and heating temperatures. For instance, slower stirring and lower temperatures during cutting result in larger curds and less whey expulsion, ideal for cheeses like Cheddar. Conversely, faster cutting and higher temperatures produce smaller curds and more whey release, suitable for cheeses like Ricotta. Mastering these variables allows cheese makers to tailor the curd’s characteristics to specific cheese types.

Practical tips for optimizing curd formation include ensuring milk freshness, as older milk may have weaker casein micelles, leading to poor coagulation. Maintaining consistent temperatures during coagulation is equally vital; fluctuations can disrupt enzyme activity and yield uneven curds. For home cheese makers, using a thermometer and pH meter can significantly improve results. Additionally, experimenting with different coagulants—such as microbial transglutaminase for vegetarian cheeses—can offer unique textures and flavors. By focusing on the casein aggregation process, cheese makers can elevate their craft, turning a simple science into a culinary masterpiece.

Can Cats Eat Cheese? Exploring the Effects on Your Feline Friend

You may want to see also

Casein Types: αs1, αs2, β, κ caseins and their specific roles in coagulation

Milk proteins coagulate during cheese making, and the primary category responsible for this process is casein. Caseins are phosphoproteins that make up approximately 80% of bovine milk proteins, forming micelles—large, colloidal structures stabilized by calcium and phosphorus. Among the casein types, αs1, αs2, β, and κ caseins play distinct roles in coagulation, each contributing uniquely to the structure, texture, and functionality of cheese. Understanding their specific functions is essential for optimizing cheese production and quality.

Αs1-Casein and αs2-Casein: The Structural Framework

These two caseins are the most abundant, comprising about 35-40% of total casein content. αs1-casein and αs2-casein are highly hydrophobic, forming the core of the casein micelle. During coagulation, they provide structural stability and contribute to the firmness of the curd. αs1-casein, in particular, is more prone to proteolysis, which influences the ripening process in cheeses like Cheddar. αs2-casein, on the other hand, is more resistant to breakdown, maintaining the integrity of the micelle under acidic conditions. Their interplay determines the curd's ability to retain moisture and resist syneresis, making them critical for cheeses requiring a dense, compact texture.

Β-Casein: The Elasticity Enhancer

Accounting for approximately 35% of casein, β-casein is essential for the elasticity of the curd. Its flexible structure allows it to stretch and form a network that resists fracture, a property vital for cheeses like Mozzarella. During coagulation, β-casein interacts with κ-casein to create a balanced matrix, preventing excessive toughness or brittleness. Studies show that variations in β-casein alleles (e.g., A1 vs. A2) can affect curd yield and texture, with A2 β-casein often associated with softer, more pliable curds. For cheesemakers, monitoring β-casein content is key to achieving the desired stretchability in pasta filata cheeses.

Κ-Casein: The Coagulation Regulator

Κ-Casein, though present in smaller amounts (10-15%), is the linchpin of coagulation. Its glycoprotein structure stabilizes the micelle by steric hindrance, preventing premature aggregation. However, during cheesemaking, chymosin (or rennet) specifically cleaves κ-casein, removing its C-terminal tail (known as the para-κ-casein fragment). This exposes the hydrophobic core of the micelle, triggering aggregation and curd formation. Without κ-casein, uncontrolled coagulation would occur, leading to weak, grainy textures. Its role is so critical that even slight variations in κ-casein content can significantly impact curd yield and moisture retention, as seen in low-κ-casein milk from certain breeds.

Practical Considerations for Cheesemakers

To harness the unique roles of these caseins, cheesemakers must consider milk source, pH, temperature, and enzyme type. For example, using microbial transglutaminase can crosslink αs1- and αs2-casein to improve curd firmness in low-fat cheeses. In contrast, adjusting rennet dosage can modulate κ-casein cleavage, optimizing coagulation time for specific cheese varieties. For aged cheeses, monitoring proteolysis of αs1-casein is crucial for flavor development, while β-casein content dictates the meltability of processed cheeses. By tailoring processes to the casein profile, producers can achieve consistent quality and innovate with new textures.

In summary, αs1, αs2, β, and κ caseins are not interchangeable components but specialized players in the coagulation process. Their unique structures and interactions dictate curd formation, texture, and functionality, making them indispensable in cheesemaking. Mastering their roles allows artisans and industrial producers alike to craft cheeses that meet specific sensory and structural requirements.

Wendy's Chili Chips and Cheese: Still on the Menu?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Acid Coagulation: Use of acids like lactic acid to coagulate milk in some cheeses

Milk proteins, primarily casein, are the key players in cheese making, and their coagulation is essential for transforming liquid milk into solid cheese. Among the various methods of coagulation, acid coagulation stands out as a unique and traditional approach, particularly in the production of certain types of cheese. This method relies on the use of acids, such as lactic acid, to lower the pH of milk, causing the casein proteins to precipitate and form a curd.

The Science Behind Acid Coagulation

Lactic acid, a natural byproduct of lactose fermentation by lactic acid bacteria, is the primary acid used in this process. As the bacteria metabolize lactose, they produce lactic acid, which gradually lowers the milk's pH. When the pH drops below approximately 4.6, the casein proteins start to coagulate. This is because the acidic environment disrupts the electrostatic repulsion between casein micelles, allowing them to aggregate and form a gel-like structure. The optimal pH range for acid coagulation is typically between 4.4 and 4.6, depending on the specific cheese variety and desired texture.

Cheese Varieties and Acid Coagulation

Cheeses that rely on acid coagulation are often characterized by their soft, spreadable textures and tangy flavors. Examples include cottage cheese, cream cheese, and some varieties of fresh cheeses like queso fresco. In these cheeses, the curd is not cut or heated, allowing the lactic acid bacteria to continue fermenting the lactose and contributing to the cheese's characteristic flavor profile. For instance, in cottage cheese production, a direct-set mesophilic culture is added to milk, which ferments the lactose and lowers the pH to around 4.5-4.6. Once the desired pH is reached, the curd is gently stirred, cut into small pieces, and drained to form the final product.

Practical Considerations and Tips

When using acid coagulation in cheese making, it's essential to monitor the pH carefully, as over-acidification can lead to a bitter taste and a weak curd. A pH meter or test strips can be used to track the pH during fermentation. Additionally, the choice of lactic acid bacteria culture plays a critical role in determining the flavor and texture of the final cheese. For optimal results, follow these guidelines: maintain a milk temperature of 20-25°C (68-77°F) during fermentation, use a culture dosage of 0.5-1% of the milk volume, and allow sufficient time for fermentation (typically 12-24 hours) to achieve the desired pH. By understanding the nuances of acid coagulation and applying these practical tips, cheese makers can create high-quality, flavorful cheeses that showcase the unique characteristics of this traditional coagulation method.

Comparative Advantages and Limitations

Compared to rennet coagulation, acid coagulation offers several advantages, including simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and the ability to produce cheeses with distinct flavors and textures. However, it also has limitations, such as the potential for bitterness if the pH is not carefully controlled and the inability to produce hard or semi-hard cheeses. Despite these limitations, acid coagulation remains a valuable technique in the cheese maker's toolkit, particularly for producing fresh, soft cheeses. By harnessing the power of lactic acid bacteria and carefully managing the fermentation process, cheese makers can create a wide range of delicious and unique cheeses that highlight the versatility and complexity of milk proteins.

Does Cotija Cheese Melt Well on Tortilla Chips? A Tasty Experiment

You may want to see also

Heat Treatment: Effect of temperature on protein denaturation and coagulation in cheese making

Milk proteins, primarily caseins, are the cornerstone of cheese making, with their coagulation being pivotal to the process. However, the role of heat treatment in this transformation is equally critical, as temperature directly influences protein denaturation and coagulation. Understanding this relationship is essential for achieving desired cheese textures and flavors.

The Delicate Dance of Heat and Protein

Heat treatment in cheese making is a precise art. At temperatures below 60°C (140°F), milk proteins remain largely unaffected, retaining their native structure. However, as temperatures rise above this threshold, denaturation begins. This process alters the protein's tertiary and secondary structures, exposing previously hidden hydrophobic regions. These exposed areas then interact with each other, leading to aggregation and eventual coagulation.

The key players in this heat-induced coagulation are the whey proteins, particularly β-lactoglobulin and α-lactalbumin. While caseins are the primary coagulating agents in traditional cheese making (through the action of rennet), heat treatment significantly contributes to the overall coagulation process, especially in cheeses like ricotta and paneer.

Temperature Zones and Their Effects

- 60-70°C (140-158°F): At this range, whey proteins begin to denature, leading to a slight increase in viscosity and a more delicate curd formation. This is often used in the production of soft, fresh cheeses.

- 70-80°C (158-176°F): Here, denaturation intensifies, causing more extensive whey protein aggregation and a firmer curd. This range is suitable for semi-hard cheeses like mozzarella.

- Above 80°C (176°F): Prolonged exposure to temperatures above 80°C can lead to excessive protein denaturation, resulting in a tough, rubbery curd unsuitable for most cheese types.

Practical Considerations

When applying heat treatment in cheese making, several factors require consideration:

- Time: The duration of heat treatment is crucial. Longer exposure times at lower temperatures can achieve similar effects to shorter times at higher temperatures.

- pH: The pH of the milk influences protein denaturation. Lower pH values (more acidic) can accelerate denaturation.

- Fat Content: Higher fat content can protect proteins from heat damage to some extent.

Optimizing Heat Treatment for Desired Results

By carefully controlling temperature, time, and other factors, cheesemakers can manipulate the degree of protein denaturation and coagulation to achieve specific textural and flavor profiles. For example, a gentle heat treatment at 65°C for 30 minutes might be ideal for a creamy ricotta, while a more intense treatment at 75°C for 15 minutes could be used for a firmer cheddar-style cheese.

Understanding the intricate relationship between heat and protein behavior empowers cheesemakers to craft cheeses with consistent quality and unique characteristics.

Cheese Escape's 30-Second Timer: Unlocking Secrets and Strategies

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The primary category of milk protein that is coagulated in cheese making is casein.

Casein is crucial because it coagulates when exposed to rennet or acid, forming a curd that is the foundation of cheese.

Yes, casein consists of four main types: αs1-casein, αs2-casein, β-casein, and κ-casein, with κ-casein playing a key role in coagulation.

Whey proteins, such as beta-lactoglobulin and alpha-lactalbumin, remain in the liquid whey and are not coagulated during the cheese-making process.

No, cheese cannot be made without coagulating casein, as it is the primary protein responsible for forming the curd structure in cheese.