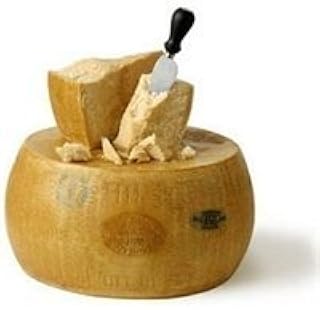

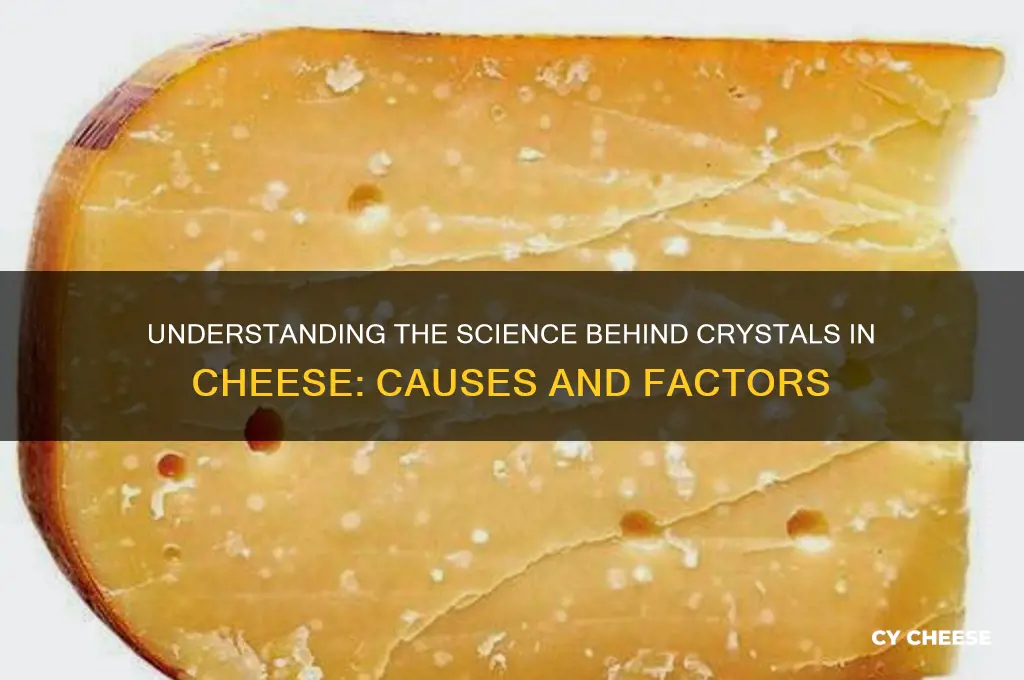

Crystals in cheese, often noticed as small, crunchy particles, are a natural occurrence that can develop during the aging process. These crystals, primarily composed of calcium lactate or tyrosine, form when moisture evaporates or when certain proteins and minerals concentrate over time. Factors such as the type of milk used, aging conditions, and the specific cheese variety play significant roles in their formation. While some cheeses, like aged Parmesan or Gouda, are prized for their crystalline texture, others may develop crystals due to improper storage or extended aging. Understanding the causes of these crystals not only sheds light on the chemistry of cheese but also helps cheese enthusiasts appreciate the nuances of this beloved dairy product.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Cause | Aging process, high fat content, protein breakdown, and calcium lactate formation. |

| Cheese Types Affected | Aged cheeses like Parmesan, Gruyère, Gouda, and aged Cheddar. |

| Crystal Composition | Primarily calcium lactate crystals, occasionally tyrosine crystals. |

| Texture Impact | Adds a crunchy, sandy, or gritty texture to the cheese. |

| Flavor Impact | Enhances nutty, savory, or umami flavors in aged cheeses. |

| Temperature Influence | Crystals form more readily in cooler aging conditions. |

| Moisture Content | Lower moisture content in aged cheeses promotes crystal formation. |

| Aging Time | Longer aging periods increase the likelihood of crystal development. |

| Health Impact | Crystals are harmless and do not affect the cheese's safety. |

| Consumer Perception | Often considered a desirable trait in aged cheeses, indicating quality. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Role of Calcium Lactate: Excess calcium lactate precipitates, forming gritty crystals in aged cheeses

- Effect of Aging Time: Longer aging increases crystal formation due to moisture loss and concentration

- Impact of pH Levels: Lower pH accelerates calcium lactate crystallization in cheese structure

- Milk Source Variations: Cow, goat, or sheep milk affect mineral content, influencing crystal development

- Processing Techniques: Heating and cooling methods can disrupt proteins, promoting crystal formation

Role of Calcium Lactate: Excess calcium lactate precipitates, forming gritty crystals in aged cheeses

Calcium lactate crystals, often mistaken for salt or protein deposits, are a common yet misunderstood feature in aged cheeses. These tiny, white, gritty particles form when calcium lactate—a natural byproduct of lactic acid fermentation—precipitates out of the cheese matrix. While some cheese enthusiasts appreciate the added texture, others find it unappealing. Understanding the role of calcium lactate is crucial for cheesemakers aiming to control or enhance this phenomenon.

The formation of calcium lactate crystals is a chemical process influenced by pH, moisture content, and aging conditions. As cheese ages, its pH drops, causing calcium lactate to become less soluble. When the concentration exceeds its solubility threshold—typically around 2-3% in cheese—it precipitates, forming crystals. This is more common in harder, longer-aged cheeses like Parmesan or aged Gouda, where moisture loss concentrates the calcium lactate. Cheesemakers can manipulate this process by adjusting the starter culture, salt concentration, or aging environment to either encourage or inhibit crystal formation.

For home cheesemakers, controlling calcium lactate crystals requires precision. Start by monitoring the pH during aging; aim for a gradual drop to below 5.2, as rapid changes can accelerate crystal formation. Maintain consistent humidity levels (around 85%) and temperatures (35-45°F) to slow moisture loss. If crystals are undesirable, reduce the aging time or increase moisture content slightly. Conversely, to promote crystals, extend aging and allow for more moisture evaporation. Adding calcium chloride (0.2-0.3% of milk weight) during production can also increase calcium levels, though this must be balanced to avoid bitterness.

Comparatively, calcium lactate crystals differ from other cheese crystals, such as tyrosine (found in aged Swiss or Cheddar), which are larger and more irregular. While tyrosine crystals form from protein breakdown, calcium lactate crystals are purely mineral-based. This distinction is key for cheesemakers and consumers alike, as it influences texture and perception. For instance, calcium lactate crystals are often described as "sandy," whereas tyrosine crystals are "crunchy." Recognizing these differences allows for better control over the final product.

In conclusion, calcium lactate crystals are a natural, manageable aspect of aged cheese production. By understanding the science behind their formation and employing specific techniques, cheesemakers can either embrace or avoid these gritty particles. Whether seen as a flaw or a feature, calcium lactate crystals offer a unique textural experience that highlights the complexity of aged cheeses. For those seeking to master this aspect of cheesemaking, patience, precision, and experimentation are key.

Quickly Soften Cream Cheese: Tips for Reaching Room Temp Fast

You may want to see also

Effect of Aging Time: Longer aging increases crystal formation due to moisture loss and concentration

As cheese ages, its moisture content gradually decreases, leading to a concentration of milk solids and minerals. This process is particularly pronounced in hard and semi-hard cheeses, where the transformation is both a science and an art. The longer a cheese is aged, the more pronounced this effect becomes, setting the stage for the development of those coveted, crunchy crystals that cheese enthusiasts adore.

Consider the aging process as a delicate balance between time, temperature, and humidity. In the first few months, the cheese loses moisture at a relatively rapid rate, causing the milk proteins and fats to coalesce. As this continues, the concentration of lactose and minerals, such as calcium lactate, increases. These minerals, now more densely packed, begin to form tiny, crystalline structures. For instance, in a cheese like Parmigiano-Reggiano, aging for 12 months results in a moderate crystal formation, while extending this period to 24 months or more can lead to a significantly higher density of these crunchy bits.

The science behind this is straightforward yet fascinating. Calcium lactate crystals, the most common type found in aged cheeses, form when the lactose molecules break down and recombine with calcium ions. This reaction is accelerated in drier environments, which is why controlled aging conditions are crucial. Cheesemakers often aim for a specific humidity level, typically around 80-85%, to manage moisture loss without completely halting it. Too much moisture, and the cheese may become soft or develop unwanted mold; too little, and it can become overly dry and brittle.

From a practical standpoint, achieving the desired crystal formation requires precision. For home cheesemakers or those looking to experiment, monitoring the aging environment is key. Use a hygrometer to track humidity and adjust as needed by misting the cheese or using a humidifier. Temperature control is equally important, ideally kept between 50-55°F (10-13°C). Regularly flipping the cheese ensures even moisture loss and prevents the formation of large, undesirable crystals.

The takeaway is clear: longer aging times, when managed correctly, enhance crystal formation by concentrating minerals and reducing moisture. This process not only elevates the texture of the cheese but also deepens its flavor profile, creating a more complex and satisfying experience. Whether you're a cheesemaker or a connoisseur, understanding this relationship allows you to appreciate—or craft—cheeses with the perfect balance of crunch and creaminess.

Mastering Dragonslayer Armor: Easy Cheesing Strategies for Quick Wins

You may want to see also

Impact of pH Levels: Lower pH accelerates calcium lactate crystallization in cheese structure

The pH level in cheese is a critical factor that can significantly influence the formation of calcium lactate crystals, those tiny, crunchy bits often found in aged cheeses like Parmesan or aged Gouda. A lower pH environment accelerates this crystallization process, transforming the cheese's texture and flavor profile. But how does this happen, and what does it mean for cheese makers and enthusiasts?

Imagine a cheese aging in a cool, dark cellar. As the cheese matures, its pH naturally decreases due to the breakdown of proteins and lactose by bacteria. When the pH drops below 5.3, the solubility of calcium lactate decreases, causing it to precipitate out of the cheese matrix. This is where the magic happens: calcium lactate molecules begin to align and form crystals. The lower the pH, the faster this process occurs, as the acidic conditions promote the dissociation of calcium and lactate ions, making them more available to form crystals. For instance, a pH of 5.0 can lead to noticeable crystallization within 6–12 months of aging, while a pH of 5.5 might take 18–24 months to achieve the same effect.

From a practical standpoint, cheese makers can manipulate pH levels to control crystallization. Adding specific starter cultures that produce lactic acid more rapidly can lower the pH faster, encouraging earlier crystal formation. However, caution is necessary—a pH that drops too low (below 4.8) can lead to excessive acidity, negatively impacting flavor and texture. For home cheese makers, monitoring pH during aging is crucial. Using pH strips or a digital meter, aim to maintain a pH between 5.0 and 5.3 for optimal crystal development without compromising quality.

Comparatively, cheeses with higher pH levels, such as fresh mozzarella or young cheddar, rarely develop these crystals because their pH remains above 5.5, keeping calcium lactate in solution. This highlights the delicate balance between acidity and crystallization. For aged cheeses, embracing a lower pH is key to achieving that desirable crunchy texture, but it requires precision and patience.

In conclusion, understanding the impact of pH on calcium lactate crystallization empowers cheese makers to craft cheeses with specific textures and flavors. By controlling pH levels, they can either enhance or inhibit crystal formation, tailoring the final product to meet consumer preferences. Whether you're a professional or a hobbyist, mastering this aspect of cheese science opens up a world of possibilities in the art of cheese making.

Does Cheese Feed Candida? Unraveling the Dietary Connection and Myths

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Milk Source Variations: Cow, goat, or sheep milk affect mineral content, influencing crystal development

The type of milk used in cheesemaking is a pivotal factor in the development of crystals, those delightful crunchy bits that elevate the texture of aged cheeses. Cow, goat, and sheep milk each bring distinct mineral profiles to the table, which significantly influence the formation and prevalence of these crystals. Understanding these differences allows cheesemakers to harness the unique qualities of each milk source, crafting cheeses with specific textural characteristics.

Cow's milk, the most commonly used in cheesemaking, typically contains higher levels of calcium and phosphate compared to goat or sheep milk. These minerals are essential for crystal formation, as they precipitate out of the cheese matrix during aging, forming the characteristic crunchy bits. For instance, Parmigiano-Reggiano, made exclusively from cow's milk, is renowned for its abundant crystals, a result of its high mineral content and long aging process.

Goat's milk, on the other hand, has a lower pH and smaller fat globules, which can affect the way minerals interact during aging. While goat's milk cheeses can develop crystals, they are generally fewer and smaller compared to those in cow's milk cheeses. This is partly due to the lower calcium and phosphate levels in goat's milk. However, the unique flavor profile of goat's milk cheeses often compensates for the reduced crystal formation, offering a tangy, bright alternative.

Sheep's milk stands out for its high fat and protein content, as well as elevated levels of certain minerals like magnesium. This richness can lead to a denser cheese with a smoother texture, but it also means that crystals, when they do form, are often larger and more pronounced. Pecorino Romano, a sheep's milk cheese, is a prime example, featuring noticeable crystals that complement its robust, savory flavor.

To maximize crystal development in cheese, consider the following practical tips: use milk with higher mineral content, such as cow's milk for abundant crystals, or sheep's milk for larger, more distinct ones. Extend the aging process, as longer aging allows more time for minerals to precipitate. Finally, maintain optimal humidity and temperature conditions during aging, as these factors also influence crystal formation. By carefully selecting the milk source and controlling the aging environment, cheesemakers can craft cheeses with the perfect balance of flavor and texture, crystals included.

Should You Remove the Outer Layer of Brie Cheese? A Guide

You may want to see also

Processing Techniques: Heating and cooling methods can disrupt proteins, promoting crystal formation

Cheese crystals, those delightful crunchy surprises in aged cheeses like Parmesan or aged Gouda, aren’t random accidents. They’re the result of precise processing techniques, particularly the way heat and cold are applied during production. Proteins in milk, specifically casein, are sensitive to temperature changes. When cheese is heated or cooled too rapidly, these proteins can denature or realign, creating pockets where lactose and other minerals accumulate over time. This accumulation eventually crystallizes, forming the distinctive texture we crave.

Consider the aging process of Parmigiano-Reggiano, where temperature control is critical. After the initial heating to coagulate the curds, the cheese is slowly cooled over several days. If this cooling is rushed, the proteins can’t settle evenly, leading to uneven crystal formation. Conversely, controlled heating during the early stages of cheesemaking can encourage the breakdown of lactose into lactic acid, which later contributes to crystal growth. The key lies in balancing these thermal stresses to promote, not hinder, the desired outcome.

For home cheesemakers, understanding this protein-temperature relationship is essential. When crafting hard cheeses, avoid drastic temperature shifts during pressing or aging. Aim for gradual changes: heat curds to 50–55°C (122–131°F) during cooking, then cool them slowly over 24–48 hours. During aging, maintain a stable environment around 12–15°C (54–59°F) with consistent humidity. These steps ensure proteins remain intact enough to allow for controlled crystal formation without disrupting the cheese’s structure.

The science behind this is straightforward: rapid temperature changes cause proteins to clump or misfold, creating voids where lactose and calcium lactate concentrate. Over months or years of aging, these concentrations solidify into crystals. Industrial producers often use precise temperature-controlled rooms to mimic this process, but even small-scale artisans can achieve similar results with careful monitoring. The takeaway? Patience and precision in heating and cooling aren’t just best practices—they’re the foundation of crafting cheese with perfect crystals.

Finally, while crystals are often celebrated, not all cheeses benefit from this trait. Fresh cheeses like mozzarella or ricotta rely on smooth, unbroken protein structures, so rapid cooling is actually desirable to prevent crystallization. Knowing when to encourage or avoid this process allows cheesemakers to tailor their techniques to the desired outcome. Whether you’re aiming for a crystalline bite or a creamy texture, mastering temperature control is the secret to unlocking cheese’s full potential.

Cheese-Free Bean Tortilla: Simple, Flavorful, and Plant-Based Recipe Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Crystals in cheese are typically formed by the presence of tyrosine, an amino acid found in milk proteins. Over time, especially in aged cheeses, tyrosine can precipitate and form small, crunchy crystals, which are harmless and often considered a desirable trait in certain cheeses.

No, crystals in cheese are not a sign of spoilage. They are a natural result of the aging process and are more common in hard, aged cheeses like Parmesan or aged Gouda. If the cheese smells or tastes off, it may be spoiled, but crystals alone do not indicate spoilage.

Crystals in cheese cannot be entirely prevented, as they are a natural part of the aging process. However, controlling factors like temperature, humidity, and aging time can influence their formation. Some cheesemakers may adjust these conditions to either encourage or minimize crystal development, depending on the desired cheese characteristics.