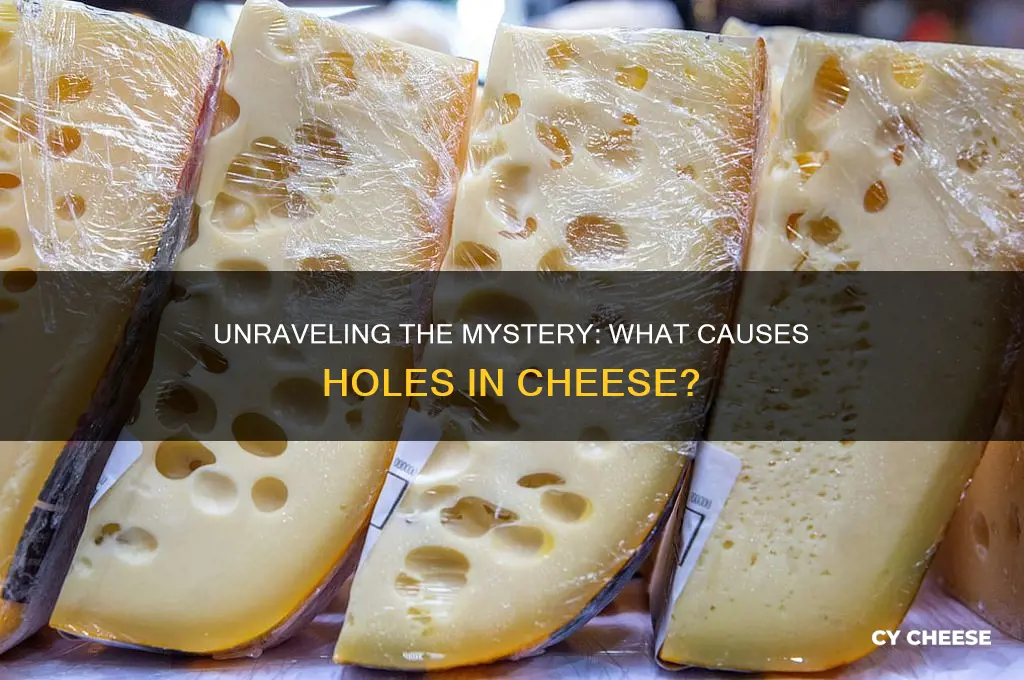

Holes in cheese, often associated with varieties like Swiss or Emmental, are the result of a fascinating natural process during cheese production. These holes, technically called eyes, form due to the activity of specific bacteria, such as *Propionibacterium freudenreichii*, which produce carbon dioxide gas as they metabolize lactic acid in the cheese curd. As the cheese ages, the gas becomes trapped within the curd, creating bubbles that expand and eventually form the characteristic holes. Factors like humidity, temperature, and the cheese's density during production also influence the size and distribution of these eyes, making them a unique and intentional feature of certain cheese types.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Cause of Holes | Carbon dioxide gas produced by bacteria during fermentation (e.g., Propionibacterium freudenreichii in Swiss cheese). |

| Cheese Types Affected | Primarily Swiss-type cheeses (e.g., Emmental, Gruyère, Appenzeller). |

| Bacterial Activity | Propionibacterium bacteria metabolize lactic acid, producing propionic acid and carbon dioxide gas. |

| Gas Formation | Carbon dioxide forms bubbles in the curd, which expand during aging, creating holes. |

| Curd Structure | A loose, open curd structure allows gas bubbles to expand and form holes. |

| Aging Process | Holes develop during the aging process as the cheese matures. |

| Hole Size | Varies depending on cheese type and aging time, typically 1–2 cm in diameter. |

| Impact on Texture | Holes contribute to a lighter, airy texture in the cheese. |

| Other Factors | Milk quality, starter cultures, and humidity during aging can influence hole formation. |

| Non-Swiss Cheeses | Some cheeses (e.g., Gouda, Cheddar) may have small holes due to different bacteria or gas formation processes. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Bacterial Gas Production: Specific bacteria release CO2 during fermentation, creating holes in cheese

- Propionic Acid Fermentation: Propionibacteria produce gas, leading to larger holes in Swiss-type cheeses

- Curd Stretching Techniques: Stretching curd traps air pockets, forming holes in cheeses like mozzarella

- Aging and Ripening: Enzymes break down proteins, allowing gas to expand and create holes over time

- Milk Composition: Higher fat and protein content in milk can influence hole formation during cheesemaking

Bacterial Gas Production: Specific bacteria release CO2 during fermentation, creating holes in cheese

The distinctive holes in Swiss cheese, scientifically known as *eyes*, are not a flaw but a feature crafted by specific bacteria during fermentation. These bacteria, primarily *Propionibacterium freudenreichii*, metabolize lactic acid in the curd and release carbon dioxide (CO2) as a byproduct. As the cheese ages, this gas becomes trapped within the semi-solid matrix, forming the characteristic holes. This process, called *eye formation*, is a hallmark of cheeses like Emmental and Gruyère, where the size and distribution of holes are carefully controlled to meet quality standards.

To achieve optimal eye formation, cheesemakers must maintain precise conditions during production. The curd is heated to around 35–37°C (95–98.6°F) and held at this temperature for several hours to encourage bacterial activity. The dosage of *Propionibacterium* cultures is critical, typically added at a rate of 0.5–1% of the milk weight. Too little culture results in small, sparse holes, while excessive amounts can lead to uneven or oversized eyes. Humidity and salt concentration in the aging environment also play a role, as low moisture or high salt can inhibit bacterial gas production.

A comparative analysis of hole formation in different cheeses reveals the uniqueness of this bacterial process. For instance, the holes in Cheddar or Gouda are absent because these cheeses rely on different bacteria and aging techniques. In contrast, the eyes in Swiss cheese are a direct result of *Propionibacterium*'s CO2 production, which distinguishes it from other varieties. This specificity highlights the importance of microbial selection and environmental control in cheesemaking, where even slight variations can alter the final product's texture and appearance.

For home cheesemakers, replicating this process requires attention to detail. Start by sourcing high-quality *Propionibacterium* cultures and ensuring the milk is free of antibiotics, which can inhibit bacterial growth. After adding the culture, monitor the curd's pH, aiming for a gradual drop to around 5.3–5.5 during fermentation. Aging should occur in a cool, humid environment (10–12°C or 50–54°F) for 2–4 months, with regular turning to ensure even hole development. Patience is key, as rushing the process can result in poorly formed eyes or off-flavors.

The takeaway is that bacterial gas production is both a science and an art. By understanding the role of *Propionibacterium* and controlling variables like temperature, culture dosage, and aging conditions, cheesemakers can consistently produce cheeses with the desired eye characteristics. This process not only enhances the cheese's visual appeal but also contributes to its unique flavor profile, making it a prized technique in the world of artisanal cheesemaking.

Perfectly Baked Cheesy Potatoes: Easy Oven Recipe for Creamy Delight

You may want to see also

Propionic Acid Fermentation: Propionibacteria produce gas, leading to larger holes in Swiss-type cheeses

The distinctive large holes in Swiss-type cheeses like Emmental and Gruyère are not the result of air bubbles or mechanical processes but the handiwork of microscopic organisms. Propionibacteria, a group of bacteria essential to the production of these cheeses, play a starring role in this phenomenon. During the aging process, these bacteria ferment lactate in the cheese into propionic acid, acetic acid, and carbon dioxide. It is the carbon dioxide gas that becomes trapped within the curd matrix, forming the characteristic holes, or "eyes," as the cheese matures.

To understand the process better, consider the environment in which these bacteria thrive. Swiss-type cheeses are typically aged at temperatures between 18°C and 24°C (64°F to 75°F) for several months. During this time, propionibacteria slowly metabolize the available lactate, a byproduct of earlier fermentation by lactic acid bacteria. The reaction can be represented as follows: C3H6O3 (lactate) → C2H5COOH (propionic acid) + CH3COOH (acetic acid) + CO2 (carbon dioxide). The gas produced is initially dissolved in the cheese but eventually forms bubbles as the cheese structure becomes more rigid. The size and distribution of these holes depend on factors such as the cheese's moisture content, curd density, and the activity level of the propionibacteria.

For cheesemakers aiming to control hole size, managing the fermentation process is key. Propionibacteria require a low-oxygen environment to thrive, so proper sealing of the cheese during aging is essential. Additionally, the concentration of lactate in the cheese influences the extent of gas production. Cheeses with higher lactate levels tend to develop larger holes, though excessive lactate can lead to an overly acidic flavor. Monitoring the pH during aging, ideally keeping it between 5.3 and 5.5, ensures optimal conditions for propionibacteria activity without compromising taste.

A practical tip for home cheesemakers experimenting with Swiss-type cheeses is to maintain consistent temperature and humidity during aging. Fluctuations can disrupt bacterial activity, leading to uneven hole formation. Using a cheese cave or a controlled environment like a wine fridge can help achieve the desired results. Patience is also crucial, as the eye formation process typically begins after 4 to 6 weeks of aging and continues to develop over several months.

In comparison to other cheeses with smaller holes, such as cheddar or Gouda, Swiss-type cheeses rely uniquely on propionic acid fermentation for their signature appearance. While the holes may seem like a mere aesthetic feature, they are a testament to the intricate interplay between microbiology and craftsmanship. For cheese enthusiasts, understanding this process not only deepens appreciation for the art of cheesemaking but also highlights the science behind one of the world’s most beloved foods.

Is Asiago a Cheese? Unraveling the Mystery of This Italian Delight

You may want to see also

Curd Stretching Techniques: Stretching curd traps air pockets, forming holes in cheeses like mozzarella

The art of curd stretching is a pivotal technique in cheesemaking, particularly for varieties like mozzarella, where the desired outcome is a cheese with a distinctive, hole-riddled texture. This process is not merely about transforming curds into cheese but is a delicate dance that involves trapping air pockets, which ultimately become the signature holes in the final product.

The Science Behind Stretching: When curds are stretched, a fascinating transformation occurs at a molecular level. The curd's protein structure, primarily composed of casein, aligns and forms a network that can trap air. This phenomenon is similar to blowing bubbles with gum, where the stretching action creates a thin film that encapsulates air. In cheesemaking, this process is carefully controlled to ensure the air pockets are distributed evenly, resulting in a consistent hole structure. The key lies in the curd's moisture content and temperature; too dry, and the curd becomes brittle, too wet, and it lacks the necessary elasticity for stretching.

Mastering the Stretch: Cheesemakers employ various techniques to achieve the perfect stretch. One common method is the 'pasta filata' technique, which involves heating the curd in hot water or whey, then stretching and folding it repeatedly. This process is akin to kneading dough, requiring skill and precision. The curd is stretched until it becomes smooth and glossy, indicating the formation of a uniform protein matrix. For home cheesemakers, a simple approach is to use a microwave. Place the curd in a microwave-safe bowl, add a small amount of water, and heat in short intervals, stretching the curd between each session. This method allows for better control, especially for beginners.

Troubleshooting and Tips: Achieving the right stretch can be challenging. If the curd tears easily, it might be too cold or dry. In this case, increase the temperature gradually and ensure the curd is adequately hydrated. Overstretching can also lead to a tough, chewy texture, so it's essential to monitor the process closely. For larger batches, consider using a curd mill to ensure even stretching. Additionally, the age of the curd matters; fresher curd is generally more elastic and easier to work with. Experimenting with different stretching durations and temperatures will help cheesemakers find the sweet spot for their desired hole size and distribution.

In the world of cheesemaking, curd stretching is an art that demands precision and practice. By understanding the science behind air pocket formation and employing the right techniques, cheesemakers can consistently produce cheeses with the perfect hole structure, elevating the sensory experience of their creations. This process, though intricate, is a testament to the craftsmanship involved in transforming simple curds into culinary delights.

Unveiling Liver Cheese Tubes: A Unique Culinary Delicacy Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Aging and Ripening: Enzymes break down proteins, allowing gas to expand and create holes over time

Cheese holes, those delightful pockets of air that characterize varieties like Swiss and Emmental, aren’t random accidents. They’re the result of a precise biological process tied to aging and ripening. During this phase, enzymes—primarily those from bacteria such as *Propionibacterium freudenreichii*—break down proteins like casein into propionic acid and carbon dioxide. The CO₂ gas, initially dissolved in the cheese curd, seeks escape as the cheese hardens. Over weeks or months, it expands, pushing against the matrix until it forms visible holes. This transformation isn’t just about texture; it’s a testament to the interplay of microbiology and time.

To understand this process, consider the role of temperature and humidity during aging. Ideal conditions for hole formation typically range between 59°F to 68°F (15°C to 20°C) with 90–95% humidity. At these levels, enzymes remain active, and the cheese retains enough moisture to allow gas movement. For home cheesemakers, maintaining these parameters is critical. Use a cheese cave or a wine fridge with a hygrometer, and monitor the environment weekly. If the temperature drops below 55°F (13°C), enzymatic activity slows, reducing hole formation. Conversely, higher temperatures can accelerate aging but risk uneven hole distribution.

The size and distribution of holes also depend on the cheese’s curd structure. A looser curd, achieved by cutting it into larger pieces during production, provides more space for gas to accumulate. For example, Emmental curds are cut to pea-sized pieces, while Swiss cheese curds are slightly smaller, resulting in varying hole sizes. Experimenting with curd size can yield unique textures, but caution is advised: too loose a curd may lead to cracks, while too tight a curd restricts gas expansion. Aim for uniformity in cutting to ensure consistent hole formation.

Finally, patience is the unsung hero of hole creation. Aging times vary by cheese type—Emmental requires 2–3 months, while Gruyère may take up to 10 months. Rushing this process by increasing heat or enzyme dosage can produce bitter flavors or irregular holes. Instead, embrace the timeline as an opportunity to refine your craft. Regularly inspect the cheese for signs of gas pockets, and adjust humidity if the rind appears too dry or moist. By respecting the science and art of aging, you’ll craft cheeses where every hole tells a story of precision and care.

Does Aph America Hate Cheese? Unraveling the Myth and Facts

You may want to see also

Milk Composition: Higher fat and protein content in milk can influence hole formation during cheesemaking

The size and distribution of holes in cheese, often a hallmark of varieties like Swiss or Emmental, are not random but a direct result of milk composition. Milk with higher fat and protein content tends to produce larger, more pronounced holes during the cheesemaking process. This phenomenon is rooted in the way fat and protein molecules interact with the carbon dioxide gas produced by specific bacteria during fermentation. When milk has a higher fat content, typically above 3.5% for cow’s milk, the fat globules create a more viscous environment, allowing gas bubbles to expand more freely. Similarly, protein levels above 3.2% contribute to a stronger curd structure, which traps gas more effectively. Understanding this relationship allows cheesemakers to manipulate milk composition to achieve desired hole characteristics.

To illustrate, consider the difference between milk used for holey cheeses like Emmental (often made from milk with 4% fat and 3.4% protein) and cheeses like Cheddar (typically made from milk with 2% fat and 3% protein). The higher fat and protein content in Emmental milk creates an ideal environment for *Propionibacterium freudenreichii*, the bacteria responsible for producing carbon dioxide gas during aging. As the bacteria metabolize lactate, they release gas that becomes trapped within the curd, forming the characteristic holes. In contrast, lower-fat milk produces a less viscous curd, resulting in smaller or nonexistent holes. Cheesemakers can adjust milk composition through standardization (blending milks of different fat contents) or by using cream-enriched milk to achieve specific hole sizes.

Practical tips for cheesemakers aiming to control hole formation include monitoring milk fat and protein levels before production. For instance, using milk with a fat content of 4.5% and protein content of 3.6% can yield larger holes, but this requires careful handling to avoid curd toughness. Additionally, maintaining a consistent fermentation temperature of 22–24°C (72–75°F) during the aging process ensures optimal bacterial activity. For home cheesemakers, experimenting with store-bought cream to increase milk fat content can be a simple way to observe the effect on hole formation. However, caution should be taken to avoid over-enriching the milk, as this can lead to greasy textures or uneven curd development.

Comparatively, cheeses made from milk with lower fat and protein content, such as those from goats or sheep, rarely develop large holes due to their naturally different milk composition. Goat’s milk, for example, typically contains 3.5–4% fat and 3.2% protein, but its smaller fat globules and different protein structure result in a denser curd that resists gas expansion. This highlights the importance of species-specific milk characteristics in hole formation. By contrast, cow’s milk, particularly from breeds like Brown Swiss or Simmental, naturally contains higher fat and protein levels, making it ideal for holey cheeses. Cheesemakers can leverage these differences by selecting milk sources strategically or blending milks to achieve desired outcomes.

In conclusion, milk composition plays a pivotal role in hole formation during cheesemaking, with higher fat and protein content directly influencing the size and distribution of holes. By understanding the interplay between fat, protein, and bacterial activity, cheesemakers can manipulate milk composition to create cheeses with specific hole characteristics. Whether through standardization, cream enrichment, or species selection, controlling milk composition offers a practical and precise way to achieve the desired texture and appearance in holey cheeses. This knowledge not only enhances the craft of cheesemaking but also deepens appreciation for the science behind this beloved food.

Quarter Pounder vs. Royale with Cheese: Unraveling the Iconic Burger Mystery

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Holes in cheese, also known as "eyes," are primarily caused by carbon dioxide gas produced by bacteria during the aging process. These bacteria, such as *Propionibacterium freudenreichii*, ferment lactose in the cheese, releasing gas that forms bubbles, which then create the characteristic holes.

No, not all cheeses have holes. Holes are most commonly found in Swiss-type cheeses like Emmental and Appenzeller, which are specifically cultured with bacteria that produce gas. Other cheeses, such as Cheddar or Brie, do not undergo this process and therefore do not develop holes.

No, holes in cheese are a natural part of the aging process and do not indicate spoilage. However, if the cheese has an off smell, mold (other than the intended type), or an unusual texture, it may be spoiled and should not be consumed.