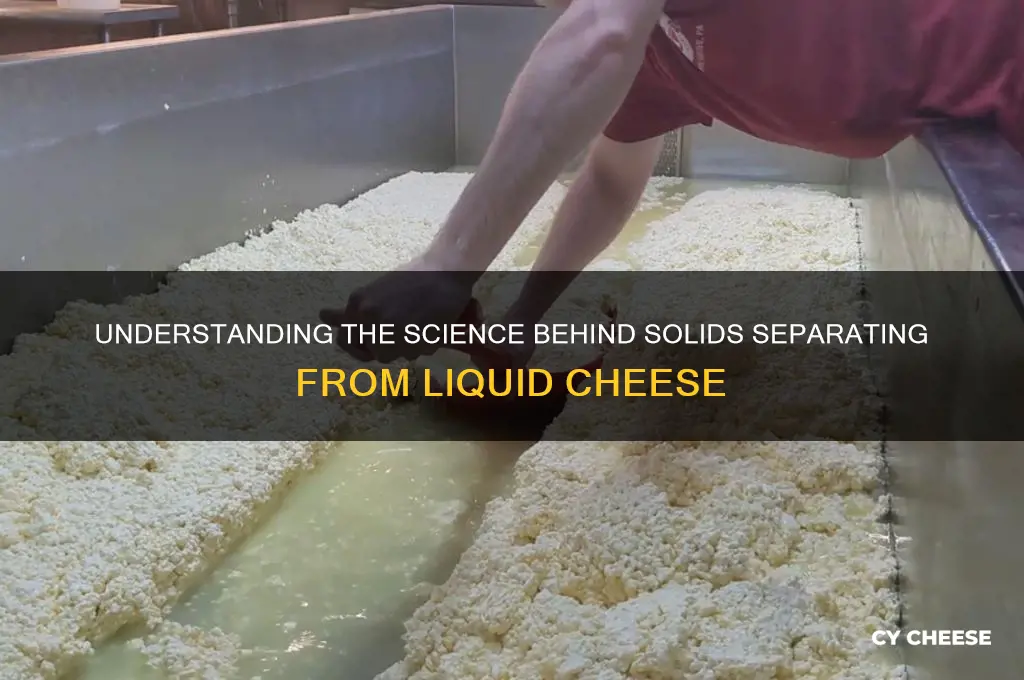

The separation of solids from liquid cheese, a phenomenon often observed in aged or improperly stored cheeses, can be attributed to several factors. Primarily, the breakdown of the cheese matrix occurs due to the activity of enzymes, particularly lipases and proteases, which degrade fats and proteins, respectively. Over time, these enzymes cause the cheese to become more liquid, allowing the curds or solid particles to settle or separate. Additionally, temperature fluctuations and improper storage conditions can accelerate this process by altering the cheese's moisture content and structure. Microbial activity, such as the growth of bacteria or mold, can also contribute to the breakdown of the cheese, further exacerbating the separation of solids from the liquid whey. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for cheese producers and consumers to maintain the desired texture and quality of the cheese.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Temperature Changes | Rapid cooling or heating can cause proteins and fats to coagulate and separate from the liquid (whey). |

| pH Imbalance | Acidification beyond the optimal pH range (typically 5.2–5.6) leads to excessive protein precipitation. |

| Over-Stirring/Agitation | Mechanical stress disrupts the emulsion, forcing solids to clump and separate. |

| Enzyme Activity | Excessive rennet or microbial enzymes (e.g., lipases, proteases) accelerate coagulation and syneresis. |

| High Salt Concentration | Salting beyond optimal levels (2–3% in most cheeses) draws moisture out, causing solids to compact and separate. |

| Low Fat Content | Reduced fat destabilizes the emulsion, as fats act as binders between proteins and liquids. |

| Microbial Overgrowth | Uncontrolled bacteria or mold produce acids/enzymes that accelerate separation. |

| Aging/Maturation | Prolonged aging increases moisture loss and protein restructuring, leading to syneresis. |

| Improper Coagulation | Incomplete or uneven coagulation during curdling results in uneven separation. |

| Whey Protein Denaturation | Heat or acid treatment denatures whey proteins, reducing their ability to stabilize the mixture. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Temperature Fluctuations: Rapid cooling or heating can cause solids to coagulate and separate from liquid cheese

- pH Imbalance: Changes in acidity levels disrupt protein bonds, leading to solid-liquid separation in cheese

- Over-Stirring: Excessive agitation breaks down curds, causing solids to release moisture and separate

- Enzyme Activity: Overactive enzymes like rennet can accelerate curdling, separating solids prematurely

- Moisture Content: High moisture levels in cheese can force whey to separate from solids

Temperature Fluctuations: Rapid cooling or heating can cause solids to coagulate and separate from liquid cheese

Rapid temperature changes can disrupt the delicate balance within liquid cheese, triggering a cascade of events that lead to solids separation. Imagine a pot of gently simmering milk. Slowly increasing heat encourages proteins to unfold and interact, forming a network that traps fat and other solids, creating a smooth, cohesive cheese curd. Now, imagine plunging that same pot into ice water. The abrupt temperature drop shocks the proteins, causing them to clump together haphazardly, expelling liquid whey and resulting in a grainy, separated texture.

This phenomenon, known as thermal shock, is a common culprit behind unwanted curd separation.

To understand why, consider the role of temperature in protein behavior. Proteins are long chains of amino acids that fold into specific shapes. These shapes determine their function and interactions. Heat provides energy, allowing proteins to move and interact more freely. In cheese making, controlled heating encourages the milk proteins casein and whey proteins to bond, forming a network that traps fat and other solids, creating the desired curd structure. However, rapid heating can overwhelm this process, causing proteins to denature and clump together randomly, leading to a coarse, separated curd. Conversely, rapid cooling can cause proteins to contract and shrink, expelling trapped liquid and causing the curd to crumble.

The optimal temperature range for cheese making varies depending on the type of cheese. For example, soft cheeses like mozzarella typically require lower temperatures (around 30-35°C) compared to hard cheeses like cheddar, which are often heated to 35-40°C.

Preventing temperature-induced separation requires careful control throughout the cheese making process. Gradual heating and cooling are essential. Use a double boiler or water bath to maintain consistent temperatures and avoid direct heat sources that can cause hot spots. Invest in a reliable thermometer to monitor temperatures accurately. For home cheese makers, a digital thermometer with a probe is invaluable. When cooling, allow the cheese to rest at room temperature for a short period before refrigerating to prevent thermal shock.

While temperature fluctuations are a common cause of solids separation, they are not the only factor. Other contributors include acidity levels, rennet dosage, and the type of milk used. However, understanding the impact of temperature and implementing careful temperature control techniques are crucial steps towards achieving consistent, high-quality cheese with a smooth, cohesive texture. Remember, patience and precision are key when crafting the perfect cheese.

Cutting Cheese Mold: How Many Inches to Safely Remove?

You may want to see also

pH Imbalance: Changes in acidity levels disrupt protein bonds, leading to solid-liquid separation in cheese

Cheese, a complex matrix of proteins, fats, and moisture, relies on delicate interactions between these components for its texture and structure. Among the critical factors influencing these interactions is pH, the measure of acidity or alkalinity. Even slight deviations in pH can disrupt the bonds holding proteins together, triggering the separation of solids from the liquid whey.

This phenomenon, known as syneresis, is a common challenge in cheese production, impacting yield, texture, and overall quality.

Imagine cheese curds as a network of protein strands, intertwined and held together by weak bonds. These bonds are sensitive to their environment, particularly pH. When pH levels drop, becoming more acidic, these bonds weaken and break. This is because the increased acidity alters the charge distribution on protein molecules, repelling them from each other. As a result, the protein network collapses, releasing trapped moisture and causing the curds to shrink and expel whey. Conversely, a rise in pH, making the environment more alkaline, can also disrupt protein interactions, leading to similar separation.

Optimum pH ranges vary depending on the cheese type. For example, cheddar cheese typically requires a pH range of 5.2 to 5.5 during curd formation, while mozzarella thrives in a slightly higher range of 5.4 to 5.6.

Controlling pH during cheese making is crucial. Rennet, a common coagulating agent, works optimally within specific pH ranges. Deviations can hinder its effectiveness, leading to weak curds prone to syneresis. Additionally, bacterial cultures used in cheese making produce lactic acid, which lowers pH. Careful monitoring and adjustment of pH throughout the process are essential to prevent excessive acidification and subsequent protein bond disruption.

Buffering agents, such as sodium citrate, can be used to stabilize pH and minimize fluctuations.

Understanding the impact of pH on protein bonds empowers cheesemakers to troubleshoot separation issues and optimize their processes. By carefully controlling pH levels, they can ensure the formation of strong curds, minimize whey loss, and produce cheese with the desired texture and consistency. This knowledge is particularly valuable for artisanal cheesemakers who rely on precise control over variables to create unique and high-quality cheeses.

Ricotta Cheese Protein Content: Is It a High-Protein Choice?

You may want to see also

Over-Stirring: Excessive agitation breaks down curds, causing solids to release moisture and separate

Cheese making is a delicate balance of art and science, where the transformation of milk into curds and whey requires precision and care. One critical phase is the handling of curds, which are fragile structures formed by the coagulation of milk proteins. Over-stirring, a seemingly minor misstep, can have significant consequences. When curds are subjected to excessive agitation, their delicate matrix begins to break down. This breakdown disrupts the bonds holding the curds together, causing them to release moisture and separate from the liquid whey. The result is a grainy texture and a loss of the desired consistency in the final cheese product.

Consider the process of stirring during cheese making as akin to gently folding ingredients in baking. Just as overmixing a batter can lead to a tough cake, over-stirring curds can compromise the integrity of the cheese. The force applied during stirring should be minimal, allowing the curds to coalesce naturally without being torn apart. For example, in the production of soft cheeses like ricotta or cottage cheese, a light, slow stirring motion is recommended. Using a slotted spoon or a whisk with gentle, deliberate movements ensures the curds remain intact. Excessive force or rapid stirring can cause the curds to disintegrate, releasing whey and creating a watery, uneven texture.

The science behind this phenomenon lies in the structure of the curds. Curds are formed when milk proteins, primarily casein, coagulate and trap moisture within their network. This network is held together by weak bonds that are susceptible to mechanical stress. When curds are over-stirred, these bonds break, and the trapped moisture is released. This not only affects the texture but also the yield, as more whey is expelled, reducing the overall volume of the cheese. For instance, in cheddar cheese making, the curds are cut and gently stirred to release whey in a controlled manner. Over-stirring at this stage can lead to a dry, crumbly texture instead of the desired firm yet smooth consistency.

To avoid over-stirring, cheese makers should adhere to specific guidelines based on the type of cheese being produced. For hard cheeses, such as Parmesan or Gruyère, the curds are stirred more vigorously initially to expel whey but must be handled with increasing care as they firm up. Soft cheeses, on the other hand, require minimal agitation throughout the process. A practical tip is to monitor the curds closely during stirring, observing their texture and moisture content. If the curds begin to look fragmented or the whey becomes excessively cloudy, it’s a sign to reduce the stirring intensity. Additionally, using a thermometer to control the temperature can help, as heat can exacerbate the effects of over-stirring by further weakening the curd structure.

In conclusion, over-stirring is a common yet avoidable mistake in cheese making that can lead to the separation of solids from liquid cheese. By understanding the delicate nature of curds and adopting gentle handling techniques, cheese makers can preserve the integrity of their product. Whether crafting a soft, creamy cheese or a hard, aged variety, the key lies in respecting the curds’ fragility and adjusting stirring methods accordingly. This attention to detail ensures the final cheese retains its desired texture, flavor, and yield, turning a potential pitfall into a masterclass in precision.

Carb Count in a 3-Egg Cheese Omelette: What You Need to Know

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$56.76

Enzyme Activity: Overactive enzymes like rennet can accelerate curdling, separating solids prematurely

Enzymes play a pivotal role in cheese making, acting as catalysts that transform milk into curds and whey. Among these, rennet stands out for its ability to coagulate milk by cleaving the protein kappa-casein, a process essential for curd formation. However, the delicate balance of enzyme activity is critical. Overactive enzymes, particularly rennet, can disrupt this equilibrium, leading to premature curdling. When rennet is added in excess—typically more than 0.02% of the milk’s weight—it accelerates the coagulation process, causing the milk proteins to clump together too quickly. This rapid separation results in a grainy, uneven curd structure, compromising the texture and yield of the final cheese.

To illustrate, consider the traditional cheddar-making process. A standard rennet dosage of 0.01% to 0.015% of milk weight is recommended for optimal curd formation. Exceeding this range, say by using 0.03%, can cause the curds to become rubbery and difficult to cut, as the enzyme’s overactivity hardens the protein matrix prematurely. This not only affects the cheese’s texture but also reduces its moisture content, leading to a drier, less desirable product. For home cheesemakers, precision in measuring rennet is crucial; using calibrated tools and following recipes strictly can prevent such mishaps.

The impact of overactive enzymes extends beyond texture to flavor and shelf life. Premature curdling can trap excess whey within the curds, creating pockets of liquid that foster bacterial growth and off-flavors. In aged cheeses, this can lead to undesirable fermentation or spoilage. Commercial producers often mitigate this by adjusting enzyme dosages based on milk type and temperature, as cow’s milk, for instance, requires less rennet than goat’s milk due to differences in protein composition. Home cheesemakers can emulate this by testing small batches with varying rennet concentrations to find the optimal level for their specific milk source.

A comparative analysis of enzyme activity reveals that not all coagulants behave like rennet. Microbial transglutaminase, another enzyme used in cheese making, cross-links proteins differently and is less prone to causing premature curdling when overused. However, its application requires careful consideration of reaction time and temperature. In contrast, rennet’s specificity to kappa-casein makes it both powerful and risky, underscoring the need for precision. For those experimenting with enzymes, starting with lower dosages and gradually increasing them allows for better control over the curdling process.

In conclusion, overactive enzymes like rennet can significantly disrupt the cheese-making process by accelerating curdling and causing solids to separate prematurely. Practical steps, such as adhering to recommended dosages, testing small batches, and understanding milk-specific requirements, can help mitigate these issues. By mastering enzyme activity, cheesemakers can ensure a consistent, high-quality product, whether crafting a sharp cheddar or a creamy brie. Precision in enzyme use is not just a technical detail—it’s the cornerstone of successful cheese making.

Low Fat Cheese Benefits: Healthier, Tastier, and Guilt-Free Snacking Options

You may want to see also

Moisture Content: High moisture levels in cheese can force whey to separate from solids

Cheese, a beloved dairy product, owes its texture and flavor to a delicate balance of moisture and solids. However, when this equilibrium is disrupted, particularly by high moisture levels, the whey—the liquid component—can separate from the curds, leading to an undesirable texture and appearance. This phenomenon is not merely a culinary inconvenience but a scientific process rooted in the chemistry of cheese-making.

Consider the role of moisture in cheese production. During the curdling process, enzymes or acids coagulate milk proteins, forming a solid mass (curds) and releasing whey. In cheeses with higher moisture content, such as fresh mozzarella or cottage cheese, the curds are less compact, allowing whey to pool and separate more easily. For instance, fresh mozzarella, with a moisture content of 50–60%, is particularly susceptible to whey separation if not stored properly. To mitigate this, manufacturers often use brine solutions or vacuum packaging to maintain moisture balance and prevent syneresis—the expulsion of whey from the curd matrix.

From a practical standpoint, controlling moisture levels is critical for both artisanal and industrial cheese production. For home cheese-makers, monitoring the curdling temperature and draining time can significantly impact the final moisture content. For example, heating milk to 90°F (32°C) before adding rennet promotes a firmer curd, reducing excess moisture. Additionally, pressing the curds for 12–24 hours in a cheese mold helps expel whey, achieving the desired texture. However, over-pressing can lead to dryness, so balance is key.

Comparatively, aged cheeses like cheddar or Parmesan have lower moisture contents (30–40%), making them less prone to whey separation. This is achieved through extended aging, which allows moisture to evaporate and enzymes to break down lactose, further reducing liquid retention. In contrast, soft cheeses like Brie or Camembert, with moisture levels around 50%, rely on molds and bacteria to develop flavor while managing moisture through careful rind formation and humidity control during aging.

In conclusion, high moisture levels in cheese act as a double-edged sword, contributing to its freshness and creaminess but also increasing the risk of whey separation. By understanding the science behind moisture content and employing precise techniques, cheese-makers can craft products that retain their structural integrity and sensory appeal. Whether you're a professional or a hobbyist, mastering moisture control is essential for creating cheese that stands the test of time—and the fridge.

Should Fresh Cheese Curds Be Refrigerated? Storage Tips Revealed

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Solids separate from liquid cheese due to differences in density, protein structure, and moisture content, often exacerbated by factors like temperature changes, pH shifts, or mechanical agitation.

Yes, overheating cheese can cause proteins to coagulate excessively, leading to the separation of solids (curds) from the liquid (whey).

Yes, older cheese tends to have a drier texture and more concentrated proteins, making it more prone to separation when melted or heated.

Yes, cheeses with higher moisture content (e.g., fresh cheeses) are less likely to separate, while harder, aged cheeses (e.g., cheddar) are more prone to separation when melted.

Yes, adding acids (like lemon juice) or enzymes (like rennet) can alter the cheese's pH or protein structure, causing curds (solids) to form and separate from the whey (liquid).