The peculiar tradition of beating cheese against a stick is rooted in the culinary heritage of Norway, where it’s known as *brunost* or brown cheese. This unique practice involves crafting a semi-soft, caramelized cheese by boiling whey, milk, and cream until it thickens into a rich, sticky mixture. Once cooled, the cheese is often served by slicing it and gently tapping it against a special wooden stick to create thin, delicate shavings. This method not only showcases the cheese’s distinctive texture but also enhances its sweet, nutty flavor, making it a beloved staple in Norwegian cuisine, typically enjoyed on bread or as a topping for waffles.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Origin of Cheese Beating

The practice of beating cheese against a stick, though seemingly peculiar, has roots in the rustic traditions of cheese-making, particularly in regions like the Alps and Scandinavia. Historically, this method was employed to test the firmness and quality of cheese during the aging process. By striking the cheese with a stick, artisans could gauge its texture and moisture content without cutting into it, preserving the cheese’s integrity. This technique was especially valuable in small-scale, pre-industrial cheese production, where precision and resourcefulness were paramount.

Analyzing the mechanics of cheese beating reveals its practicality. The sound and resistance produced when the stick strikes the cheese provide immediate feedback on its readiness. A hollow sound might indicate over-ripeness or air pockets, while a dull thud suggests the cheese is too dense or dry. This non-invasive method allowed cheesemakers to monitor their product’s development without wasting valuable portions. Over time, this practice became intertwined with cultural rituals, symbolizing the craftsmanship and patience required in cheese production.

To replicate this technique, start by selecting a firm cheese like Gruyère or Emmental, which are traditionally tested in this manner. Hold the cheese firmly on a stable surface and use a wooden stick or mallet to tap its surface gently. Listen for variations in sound and note the resistance. For optimal results, perform this test at room temperature, as cold cheese may yield misleading firmness. Avoid excessive force to prevent cracking the cheese. This method is best suited for aged cheeses, typically those over 6 months old, as younger cheeses are too soft for accurate assessment.

Comparatively, modern cheese-making relies on scientific tools like moisture meters and texture analyzers, rendering the stick-beating method largely ceremonial. However, its enduring presence in traditional cheese festivals and demonstrations highlights its cultural significance. In Switzerland, for instance, cheese beating is often showcased during Alpabzug (cow descent) celebrations, where it serves as a testament to centuries-old practices. This juxtaposition of old and new methods underscores the evolution of cheese craftsmanship while preserving its heritage.

In conclusion, the origin of cheese beating lies in its utility as a simple yet effective quality control method. While its practical application has diminished, its cultural resonance remains strong, offering a tangible link to the artisanal roots of cheese production. Whether as a historical curiosity or a festive tradition, cheese beating continues to captivate, reminding us of the ingenuity embedded in culinary traditions.

Soft Cheese and Newborns: What Parents Need to Know

You may want to see also

Traditional Cheese Types Used

The art of beating cheese against a stick, a tradition rooted in various cultures, often involves cheeses with specific characteristics: firmness, moisture content, and flavor profiles that withstand or enhance the process. Among traditional cheese types, Halloumi stands out as a prime example. Originating from Cyprus, this semi-hard cheese is renowned for its high melting point and rubbery texture, making it ideal for grilling, frying, or—you guessed it—beating against a stick. Its briny, slightly springy nature not only survives the impact but also adds a satisfying resistance that elevates the ritual.

Another contender is Pecorino Romano, an Italian hard cheese made from sheep’s milk. Its dense, granular texture and sharp, salty flavor make it a durable choice for such practices. While traditionally used in grating over pasta, its robustness allows it to endure physical stress without crumbling, though its hardness may require more force than Halloumi. For those seeking a milder alternative, Caciocavallo—an Italian stretched-curd cheese—offers a firm yet pliable texture. Shaped like a teardrop and often tied with a string, it’s historically associated with rustic traditions, including being slapped against surfaces to test its elasticity.

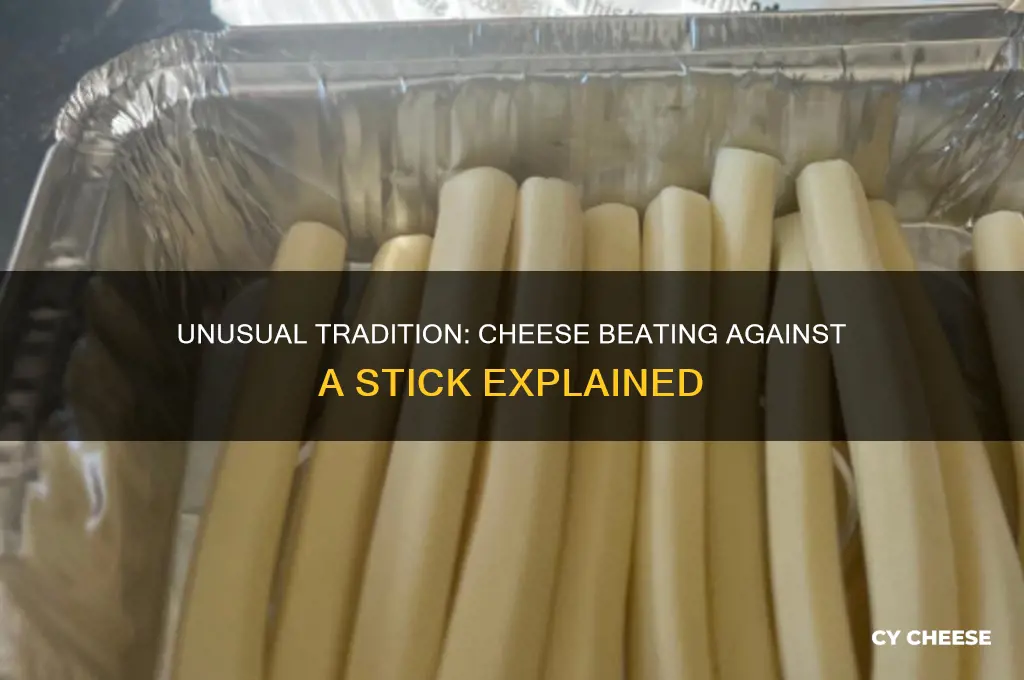

In Nordic cultures, Brunost (Norwegian brown cheese) presents an intriguing case. Made from whey and cow’s or goat’s milk, its caramelized sweetness and firm consistency make it a unique candidate. However, its brittleness requires careful handling to avoid shattering, limiting its practicality for vigorous beating. Conversely, Gouda—a Dutch cheese with a waxed rind—offers a balanced firmness and moisture level, especially in older varieties. Its nutty flavor and smooth texture make it a versatile option, though it lacks the elasticity of Halloumi or Caciocavallo.

When selecting a cheese for this tradition, consider its moisture content and age. Younger, moister cheeses like fresh Chevre or Mozzarella are too soft and will deform rather than withstand impact. Opt for semi-hard to hard varieties aged at least 3–6 months for optimal durability. Practical tip: chill the cheese slightly before use to enhance its firmness without making it brittle. Whether for cultural preservation or culinary experimentation, the right cheese transforms this act from mere novelty to a celebration of texture and tradition.

Spam, Peas, and Cheese: A Unique Recipe Worth Trying?

You may want to see also

Tools and Techniques Involved

The art of beating cheese against a stick, a tradition rooted in cultures like Norway’s *brunost* (brown cheese) making, relies on precise tools and techniques to achieve the desired texture and flavor. Central to this process is the cheese beater, a wooden or metal paddle with a flat surface designed to rhythmically strike the cheese mass. This tool must be durable yet flexible enough to withstand repeated impact without breaking. The stick itself, often a sturdy wooden rod, serves as both a structural support and a symbolic anchor for the tradition. Together, these tools form the backbone of a technique that transforms soft, warm cheese into a firm, sliceable product.

Mastering the technique requires a combination of rhythm and force. Begin by heating the cheese to a pliable 60–70°C (140–158°F), ensuring it’s soft enough to mold but not liquid. Hold the cheese mass firmly against the stick with one hand while using the beater in the other to deliver controlled, steady strikes. The goal is to compact the cheese, expelling excess moisture and creating a dense, uniform texture. For optimal results, maintain a consistent tempo—approximately 60 beats per minute—to avoid overworking the cheese, which can lead to toughness. This method, passed down through generations, balances physical effort with precision, turning a simple act into a craft.

While traditional tools remain essential, modern adaptations offer convenience without sacrificing authenticity. Electric cheese beaters, for instance, automate the striking process, reducing physical strain while maintaining the rhythmic consistency crucial to the technique. However, purists argue that the tactile feedback of manual beating allows for greater control over texture. For home enthusiasts, a DIY approach using a wooden spoon and rolling pin can suffice, though results may vary. Regardless of tools, the key lies in understanding the cheese’s transformation stages—from soft to firm—and adjusting pressure accordingly.

A critical yet often overlooked aspect is the cooling technique post-beating. After shaping the cheese against the stick, allow it to cool gradually at room temperature for 2–3 hours before transferring it to a refrigerator. Rapid cooling can cause cracking, undermining the structural integrity achieved through beating. For larger batches, consider using a cheese press to maintain even pressure during cooling, ensuring a flawless finish. This final step bridges the gap between raw technique and refined craftsmanship, turning effort into edible art.

Does Frisch's Offer Pumpkin Pie Cheesecake? A Seasonal Dessert Inquiry

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$8.99

$22.99

Cultural Significance and Rituals

The practice of beating cheese against a stick, known as *Schlagenkäse* or *slapping cheese*, is deeply rooted in Alpine traditions, particularly in regions like Austria and Switzerland. This ritual involves rhythmically striking a wheel of cheese with a stick, a process believed to enhance flavor, texture, and preservation. Beyond its practical benefits, this act is a cultural emblem, symbolizing community, craftsmanship, and the enduring connection between humans and their environment. It’s not merely about food preparation; it’s a performance, a shared experience that binds generations.

Analyzing the ritual reveals its dual purpose: preservation and celebration. In Alpine villages, where winters are harsh and resources scarce, cheese was a vital staple. Beating the cheese helped distribute salt evenly, aiding in its longevity. Yet, the act was also ceremonial, often performed during festivals or communal gatherings. The rhythmic slapping, accompanied by chants or music, transformed a mundane task into a cultural spectacle. This duality underscores how necessity and artistry intertwine in traditional practices, elevating them from functional to sacred.

To replicate this ritual, start with a young, semi-hard cheese like Bergkäse or Emmental. Use a flat, wooden stick, ensuring it’s clean and dry. Strike the cheese wheel firmly but not forcefully, maintaining a steady rhythm. Aim for 10–15 minutes of slapping per side, allowing the cheese to rest briefly between sessions. For authenticity, involve others, turning the task into a shared activity. Caution: avoid over-beating, as it can crack the cheese. The goal is to enhance, not damage, its structure.

Comparatively, this practice echoes other global food rituals, such as the Japanese art of *kintsugi* or the Native American tradition of blessing corn. Each reflects a culture’s reverence for materials and processes. However, cheese-beating stands out for its tactile, auditory, and communal dimensions. It’s a multisensory experience, where the sound of wood meeting cheese becomes a cultural signature. This uniqueness highlights how rituals can encode identity, turning simple acts into profound expressions of heritage.

In modern times, the ritual faces the threat of obsolescence, overshadowed by industrial methods. Yet, its revival in artisanal cheese-making and cultural festivals proves its enduring appeal. For enthusiasts, participating in or witnessing this practice offers more than a taste of tradition—it’s a lesson in sustainability, patience, and the value of shared labor. As a takeaway, consider this: in a world of mass production, rituals like cheese-beating remind us of the beauty in slowing down, in crafting with intention, and in savoring the process as much as the product.

Is Provolone Cheese High in Sodium? A Nutritional Breakdown

You may want to see also

Modern Adaptations and Variations

The traditional practice of beating cheese against a stick, often associated with the Dutch cheese market in Alkmaar, has inspired modern adaptations that blend cultural heritage with contemporary innovation. Today, artisanal cheesemakers are experimenting with this age-old technique to create unique textures and flavors. For instance, some producers use a modified wooden mallet instead of a stick to control the force applied, ensuring consistency while preserving the ritualistic aspect. This method is particularly popular with semi-hard cheeses like Gouda or Edam, where the beating process enhances their elasticity and richness.

One notable variation involves incorporating unconventional ingredients into the cheese before or after beating. For example, cheesemakers in the Pacific Northwest are infusing beaten cheeses with local herbs, spices, or even smoked flavors, creating a fusion of tradition and regional identity. A practical tip for home enthusiasts: start with a young Gouda, beat it gently for 5–7 minutes, and then sprinkle in dried rosemary or chili flakes for a personalized twist. This approach not only honors the original technique but also encourages creativity in the kitchen.

From a technological standpoint, modern adaptations include the use of automated machinery to replicate the beating process. These machines, designed to mimic the rhythmic motion of hand-beating, are calibrated to apply precise pressure, reducing labor while maintaining authenticity. However, purists argue that the tactile connection between the cheesemaker and the product is lost in this mechanized approach. For small-scale producers, a compromise might involve using a handheld electric beater with adjustable settings, allowing for both efficiency and craftsmanship.

A comparative analysis reveals that while traditional methods emphasize ritual and community, modern variations prioritize scalability and innovation. For instance, a Dutch cheesemaker might beat a wheel of cheese in a public market as a cultural performance, whereas a Californian producer could use the same technique to mass-produce a specialty cheese for export. Both approaches have merit, but the latter often requires stricter quality control measures, such as monitoring humidity levels during the beating process to prevent cracking.

Finally, the educational aspect of this practice has gained traction in culinary schools and workshops. Instructors teach students not only the technique but also the science behind it—how beating redistributes moisture and fat, affecting the cheese’s final texture. For beginners, start with a 2-pound block of young Gouda, beat it for 10 minutes, and observe how the cheese becomes more pliable. This hands-on learning bridges the gap between tradition and modernity, ensuring that the art of beating cheese against a stick remains relevant in a rapidly evolving food landscape.

Fold in the Cheese": Decoding Schitt's Creek's Iconic Culinary Catchphras

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The cheese traditionally beaten against a stick is Halloumi, a firm, brined cheese from Cyprus.

Halloumi is beaten against a stick during the production process to release excess whey and ensure a firmer texture, which is essential for its signature grilling and frying qualities.

No, beating cheese against a stick is a unique and traditional method specific to Halloumi production and is not commonly used for other types of cheese.