When it comes to cheese with holes, the most iconic example is Swiss cheese, specifically Emmental. These distinctive holes, known as eyes, are formed during the aging process due to carbon dioxide gas released by bacteria in the cheese. While Emmental is the most famous, other varieties like Gruyère and Appenzeller also feature similar holes, though they are typically smaller. The size and number of holes can vary depending on factors such as the cheese's production method and aging conditions. This unique characteristic not only adds to the cheese's visual appeal but also influences its texture and flavor, making it a favorite in dishes like sandwiches, fondue, and quiches.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Cheese Type | Swiss (Emmental, Appenzeller, Gruyère, etc.) |

| Holes Cause | Carbon dioxide gas bubbles produced by bacteria (Propionibacterium freudenreichii) during fermentation |

| Hole Size | Typically 1-2 cm in diameter, but can vary |

| Hole Shape | Circular or slightly irregular |

| Texture | Semi-hard, smooth, and slightly elastic |

| Flavor | Mild, nutty, and slightly sweet |

| Color | Pale yellow interior, natural rind (yellow to brown) |

| Origin | Switzerland (Emmental region), but similar cheeses produced globally |

| Aging Time | 2-12 months, depending on variety |

| Fat Content | ~45% milk fat in dry matter |

| Uses | Melting (fondue, sandwiches), snacking, pairing with wine |

| Notable Varieties | Emmental, Jarlsberg, Leerdammer, Baby Swiss |

| Hole Formation | Occurs during aging as bacteria metabolize lactic acid |

| Rind Type | Natural, hard, and brushed (for traditional varieties) |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Swiss Cheese Holes: Emmental and Appenzeller have holes due to carbon dioxide from bacteria during aging

- Hole Formation Process: Propionic bacteria create gas bubbles, forming holes as cheese matures

- Cheese Types with Holes: Swiss, Gruyère, and Jarlsberg are known for their distinctive hole patterns

- Holes and Texture: Holes indicate proper aging and contribute to the cheese's texture and flavor

- Myth vs. Reality: Holes are not from mice but from natural bacterial activity during fermentation

Swiss Cheese Holes: Emmental and Appenzeller have holes due to carbon dioxide from bacteria during aging

The distinctive holes in Swiss cheeses like Emmental and Appenzeller are not a manufacturing defect but a deliberate result of the aging process. These cavities, technically called "eyes," form due to the activity of specific bacteria that produce carbon dioxide as a byproduct of fermentation. As the cheese ages, this gas becomes trapped within the curd, creating the characteristic holes that range in size from small peas to large walnuts. Understanding this process not only demystifies the cheese’s appearance but also highlights the intricate science behind its flavor and texture development.

To achieve these holes, cheesemakers introduce propionic acid bacteria (such as *Propionibacterium freudenreichii*) during the cheese-making process. These bacteria metabolize lactate in the cheese, producing carbon dioxide and other compounds that contribute to the cheese’s nutty, slightly sweet flavor. The size and distribution of the holes depend on factors like humidity, temperature, and the duration of aging. For example, Emmental is typically aged for 3 to 6 months, during which the holes develop gradually. Appenzeller, aged similarly, also exhibits this phenomenon, though its smaller holes and stronger flavor profile distinguish it from its counterpart.

Practical tips for appreciating these cheeses include pairing Emmental with fruits or melted in dishes like fondue, where its holes allow for even melting. Appenzeller, with its more robust flavor, pairs well with hearty breads or strong wines. When purchasing, look for wheels with evenly distributed holes, as this indicates proper aging and bacterial activity. Avoid cheeses with excessive or uneven holes, which may suggest inconsistent production conditions.

Comparatively, other cheeses like Gouda or Cheddar lack these holes because they are aged under different conditions and do not involve propionic acid bacteria. This distinction underscores the uniqueness of Swiss cheeses and their reliance on specific microbial processes. By appreciating the science behind the holes, consumers can better understand why Emmental and Appenzeller stand out in the world of cheese.

In conclusion, the holes in Emmental and Appenzeller are a testament to the precision of traditional cheese-making techniques and the role of microbiology in crafting distinct flavors and textures. Whether enjoyed on a cheese board or in a recipe, these cheeses offer a fascinating glimpse into the intersection of art and science in food production. Next time you slice into a piece, remember that those holes are not just a quirk—they’re a signature of quality and craftsmanship.

Mastering the Gummi Ship: Cheesy Tactics for Kingdom Hearts 3

You may want to see also

Hole Formation Process: Propionic bacteria create gas bubbles, forming holes as cheese matures

The distinctive holes in certain cheeses, often referred to as "eyes," are not a result of air bubbles or random chance but a deliberate process driven by propionic bacteria. These microorganisms play a starring role in transforming a dense curd into a cheese with a texture that’s both airy and complex. Understanding this process not only satisfies curiosity but also highlights the precision required in cheesemaking.

Propionic bacteria, specifically *Propionibacterium freudenreichii*, are the architects behind the holes in cheeses like Emmental and Swiss. During the aging process, these bacteria metabolize lactose, producing lactic acid as a byproduct. However, their most notable contribution is the creation of carbon dioxide gas. As the cheese matures, typically over several weeks in a controlled environment, the bacteria become active, releasing gas bubbles that become trapped within the curd. Over time, these bubbles expand, forming the characteristic holes. The size and distribution of these holes depend on factors such as humidity, temperature, and the density of the curd, making each wheel of cheese unique.

To achieve optimal hole formation, cheesemakers must carefully manage the aging conditions. The ideal temperature for propionic bacteria activity ranges between 59°F and 68°F (15°C and 20°C), with a relative humidity of 85–95%. The cheese should be turned regularly to ensure even moisture distribution and prevent the rind from becoming too dry, which could inhibit bacterial activity. Additionally, the curd must be cut and stirred precisely during the initial stages of production to create a structure that allows gas bubbles to form and expand without escaping.

While the process may seem straightforward, it’s fraught with potential pitfalls. For instance, if the cheese is aged too quickly or at too high a temperature, the gas bubbles may escape before they can form holes, resulting in a dense, holeless cheese. Conversely, too much humidity can lead to mold growth, compromising the cheese’s quality. Cheesemakers often rely on experience and sensory cues, such as the aroma and texture of the cheese, to determine when conditions are just right.

For home cheesemakers or enthusiasts, replicating this process requires patience and attention to detail. Start with a high-quality milk source and follow a recipe specifically designed for holey cheeses. Invest in a cheese press and aging fridge to control temperature and humidity. Monitor the cheese regularly, noting changes in appearance and texture. While the process may take several weeks, the reward—a wheel of cheese with perfectly formed holes—is well worth the effort. Understanding the science behind hole formation not only deepens appreciation for the craft but also empowers experimentation and innovation in cheesemaking.

Converting Block Cheese: Ounces in One Pound Explained Simply

You may want to see also

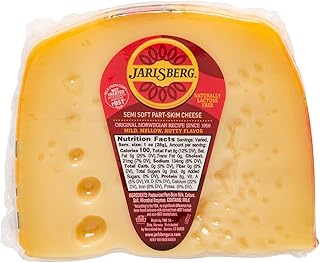

Cheese Types with Holes: Swiss, Gruyère, and Jarlsberg are known for their distinctive hole patterns

The holes in Swiss, Gruyère, and Jarlsberg cheeses aren’t a flaw—they’re a feature. Known as "eyes," these gaps form during fermentation when carbon dioxide gas gets trapped in the curd. Swiss cheese, or Emmental, boasts large, irregular holes, while Gruyère’s are smaller and more scattered. Jarlsberg falls in between, with uniform, pea-sized eyes. This isn’t just aesthetics; the holes influence texture and flavor, making these cheeses ideal for melting or pairing with wine. Understanding this process helps you appreciate why these varieties stand out in the dairy aisle.

If you’re aiming to replicate the holey texture in homemade cheese, temperature and humidity control are critical. During aging, maintain a consistent 50–55°F (10–13°C) and 85–90% humidity. For Swiss-style cheeses, add propionic acid bacteria to the culture mix—this strain produces the gas responsible for the holes. Aging time matters too: Jarlsberg requires 3–6 months, Gruyère 5–12 months, and Emmental up to a year. Skip these steps, and you’ll end up with a dense, hole-free block. Precision is key, but the payoff is a cheese that rivals store-bought varieties.

Gruyère, Jarlsberg, and Swiss cheeses aren’t just holey—they’re versatile. Gruyère’s nutty, slightly salty profile makes it a top choice for fondue or French onion soup. Jarlsberg, milder and sweeter, pairs well with fruits or crackers. Swiss cheese, with its mild, buttery taste, shines in sandwiches or grilled dishes. When melting, opt for low heat to preserve texture. For a cheese board, arrange these varieties with contrasting accompaniments: sharp jams for Gruyère, cured meats for Jarlsberg, and tangy pickles for Swiss. Each cheese’s unique hole pattern also affects how it melts, so choose based on your dish’s desired consistency.

Comparing these cheeses reveals subtle differences that cater to distinct preferences. Gruyère’s complex flavor and dense texture make it a favorite among connoisseurs, while Jarlsberg’s approachable taste appeals to a broader audience. Swiss cheese, often the most affordable of the trio, is a go-to for everyday cooking. If you’re hosting, include all three to showcase the spectrum of holey cheeses. For aging enthusiasts, Gruyère offers the most depth over time, but Jarlsberg’s consistency makes it beginner-friendly. Each variety’s hole pattern isn’t just a quirk—it’s a clue to its personality.

Starbucks Egg and Protein Box: Uncovering the Cheese Content

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Holes and Texture: Holes indicate proper aging and contribute to the cheese's texture and flavor

The presence of holes in cheese, often referred to as "eyes," is a fascinating indicator of both the cheese's aging process and its sensory qualities. These holes are not merely aesthetic quirks but are, in fact, a result of the complex biochemical reactions that occur during maturation. Specifically, the holes are formed by carbon dioxide gas released by bacteria as they break down lactic acid in the curd. This process is most commonly observed in cheeses like Swiss Emmental, Gruyère, and Appenzeller, where the eyes are a hallmark of proper aging and artisanal craftsmanship. The size and distribution of these holes can vary, but their presence is a testament to the cheese's authenticity and the precision of its production.

From a textural standpoint, the holes in cheese play a pivotal role in shaping its mouthfeel. As the cheese ages, the protein matrix surrounding the holes becomes firmer, creating a contrast between the dense, chewy exterior and the lighter, airier interior. This interplay of textures enhances the eating experience, making each bite a dynamic journey. For instance, in a well-aged Emmental, the holes contribute to a distinctive "springiness" that complements the nutty, slightly sweet flavor profile. Chefs and cheese enthusiasts often pair such cheeses with crisp wines or crusty bread to highlight this unique texture, ensuring that the sensory experience is both balanced and memorable.

Flavor development is another critical aspect influenced by the presence of holes. The gas pockets created during aging allow for greater exposure of the cheese's surface area to the surrounding environment, accelerating the breakdown of fats and proteins. This process intensifies the cheese's flavor, often resulting in deeper, more complex notes. For example, the holes in Gruyère facilitate the concentration of its signature earthy and caramelized flavors, making it a favorite for fondue and grilled cheese sandwiches. Understanding this relationship between holes and flavor can guide consumers in selecting cheeses that align with their culinary goals, whether for melting, grating, or enjoying on a cheese board.

Practical considerations for home enthusiasts include monitoring the size and consistency of holes to gauge a cheese's readiness. Smaller, evenly distributed holes typically indicate a younger cheese with a milder flavor, while larger, irregular holes suggest a longer aging period and a more robust taste. When purchasing cheese, look for wheels with well-defined eyes, as this is a sign of careful production and proper aging conditions. Additionally, storing cheese in a cool, humid environment can help preserve the integrity of the holes and maintain the desired texture and flavor. By appreciating the science behind these holes, one can elevate their cheese selection and enjoyment to a new level of sophistication.

Perfect Pairings: Best Fruits to Elevate Your Cheese Board Experience

You may want to see also

Myth vs. Reality: Holes are not from mice but from natural bacterial activity during fermentation

The holes in cheese, often whimsily dubbed "eyes," have long been the subject of culinary curiosity. A pervasive myth attributes these cavities to mice nibbling away at the cheese, a charming but entirely inaccurate notion. In reality, these holes are the result of a fascinating natural process deeply rooted in the art of cheesemaking. Understanding this process not only dispels the myth but also deepens appreciation for the science behind one of the world’s most beloved foods.

To create cheeses like Swiss Emmental or Gruyère, cheesemakers introduce specific bacteria, such as *Propionibacterium freudenreichii*, during the fermentation process. These bacteria produce carbon dioxide gas as they metabolize lactic acid in the curd. When the cheese is sealed in a warm, humid environment to age, the gas becomes trapped within the semi-solid matrix, forming bubbles that eventually become the characteristic holes. The size and distribution of these holes depend on factors like temperature, humidity, and the duration of aging—typically 2–4 months for Emmental. This controlled environment is critical; too much moisture, and the holes collapse; too little, and they fail to form.

Contrast this with the myth of mice as the culprits, which likely stems from folklore or imaginative storytelling. Mice are indeed attracted to cheese, but their teeth are neither sharp nor strong enough to create the uniform, round holes seen in these cheeses. Moreover, the holes are distributed throughout the cheese, not just on the surface where rodents might nibble. This comparison highlights how scientific understanding can replace fanciful explanations, offering a more satisfying and accurate narrative.

For home cheesemakers or enthusiasts, replicating this process requires precision. Start by culturing milk with thermophilic bacteria and adding *Propionibacterium* cultures. After coagulation and pressing, the cheese must be aged at 68–77°F (20–25°C) with high humidity. Regularly flipping the cheese ensures even hole formation. While the myth of mice is endearing, mastering the bacterial fermentation process empowers you to craft authentic, holey cheese—a testament to both tradition and science.

Mastering Wine and Cheese Pairings: Tips for Perfect Combinations

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Swiss cheese, particularly Emmental, is famous for its distinctive holes.

The holes, called "eyes," form due to carbon dioxide gas released by bacteria during the aging process.

No, the holes in Swiss cheese are natural and safe to eat; they are part of its unique characteristics.

Not all Swiss cheeses have holes; only certain varieties like Emmental and Appenzeller are known for this feature.