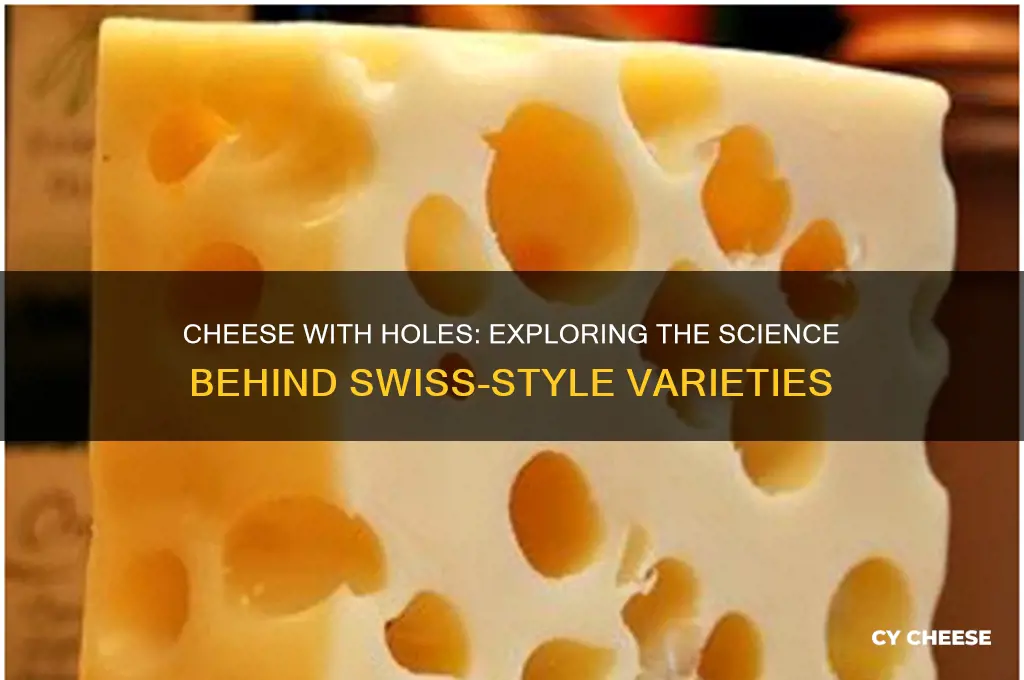

Cheese with holes, often referred to as holey cheese, is a fascinating and distinctive category of dairy products that has intrigued cheese lovers for centuries. The most iconic example is Swiss cheese, particularly Emmental, which is renowned for its large, irregularly shaped holes. These holes, technically called eyes, are a result of the cheese-making process, specifically the activity of bacteria that release carbon dioxide gas as the cheese ages. Other varieties, such as Gruyère and Appenzeller, also feature similar characteristics, though their hole sizes and distributions may vary. Understanding the science and craftsmanship behind these cheeses not only highlights their unique texture and flavor but also celebrates the rich traditions of cheese production.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Swiss Cheese Varieties: Emmental, Appenzeller, Gruyère, and others naturally develop holes during aging

- Hole Formation: Caused by carbon dioxide bubbles from bacteria in the cheese curd

- Non-Swiss Cheeses: Gouda, Provolone, and some Cheddars can also have holes

- Hole Size: Varies by cheese type, aging time, and production methods

- Myth Debunked: Not all Swiss cheeses have holes; it depends on the variety

Swiss Cheese Varieties: Emmental, Appenzeller, Gruyère, and others naturally develop holes during aging

The distinctive holes in Swiss cheeses like Emmental, Appenzeller, and Gruyère are not a defect but a hallmark of their craftsmanship. These eyes, as they’re called, form naturally during aging due to the activity of propionic acid bacteria. These bacteria, introduced during cheesemaking, produce carbon dioxide gas as they metabolize lactic acid. The gas becomes trapped in the curd, creating bubbles that expand over months of aging, resulting in the characteristic holes. This process is a testament to the precision required in Swiss cheesemaking, where humidity, temperature, and bacterial cultures must align perfectly.

To appreciate the diversity of holey Swiss cheeses, consider their unique profiles. Emmental, often the poster child for Swiss cheese, has large, irregular holes and a mild, nutty flavor. It’s ideal for fondue or melting into dishes. Gruyère, with its smaller, more scattered holes, offers a richer, earthy taste and is a staple in French onion soup. Appenzeller, less known but equally remarkable, has a tangy, spicy edge due to its brine wash during aging, and its holes are finer and more uniform. Each variety’s hole size and distribution reflect its aging process and intended use, making them distinct yet interconnected.

If you’re curious about recreating these cheeses at home, start with understanding the science. Propionic acid bacteria (PAB) are the key, but they require specific conditions: a high-moisture environment and temperatures around 20–24°C (68–75°F). For hobbyists, using pre-mixed cultures containing PAB simplifies the process. Aging times vary—Emmental takes 2–4 months, while Gruyère can age up to 10 months. Patience is critical; rushing the process yields uneven holes or none at all. Pair this knowledge with traditional recipes for the best results.

Beyond their aesthetic appeal, the holes in Swiss cheeses serve a practical purpose. They indicate proper aging and bacterial activity, ensuring the cheese’s flavor and texture have developed fully. However, hole size isn’t the sole marker of quality. Overly large holes can signify over-aging or improper handling. When selecting Swiss cheese, look for consistency in hole distribution and a smooth, elastic texture. For cooking, larger-holed varieties like Emmental melt more evenly, while Gruyère’s smaller holes retain structure in baked dishes.

Finally, the cultural significance of these cheeses cannot be overlooked. Swiss cheesemaking is a centuries-old tradition, with each region’s variety reflecting local techniques and terroir. Emmental’s origins trace back to the 13th century, while Gruyère’s production is protected by Swiss law. By choosing authentic Swiss cheeses, you’re not just enjoying a holey delight but supporting a heritage. Pair them with local accompaniments—rye bread, walnuts, or a glass of Fendant wine—to fully experience their legacy. In every bite, you taste history, science, and artistry, all encapsulated in those iconic holes.

Is Cheese Energy Dense? Uncovering Its Nutritional Value and Caloric Impact

You may want to see also

Hole Formation: Caused by carbon dioxide bubbles from bacteria in the cheese curd

The distinctive holes in certain cheeses, often referred to as "eyes," are not a result of air pockets or a quirk of the aging process but are instead a testament to the intricate dance of microbiology and chemistry. At the heart of this phenomenon lies the activity of specific bacteria, primarily *Propionibacterium freudenreichii*, which produce carbon dioxide as a byproduct of their metabolism. These bacteria are introduced during the cheesemaking process, particularly in varieties like Emmental, Gruyère, and Appenzeller. As the cheese ages, the bacteria consume lactic acid present in the curd, releasing carbon dioxide gas that becomes trapped within the semi-solid matrix, eventually forming the characteristic holes.

To understand the process more deeply, consider the environment within the cheese. During aging, the curd is warm and slightly acidic, creating ideal conditions for *Propionibacterium* to thrive. These bacteria are slow-acting, requiring several weeks to months to produce visible holes, depending on the cheese variety and aging conditions. For instance, Emmental typically develops its holes after 2–3 months of aging, while Gruyère may take slightly longer. The size and distribution of the holes can be influenced by factors such as the density of the curd, the humidity of the aging environment, and the initial bacterial concentration. Cheesemakers often control these variables to achieve the desired hole size, ranging from pea-sized to larger, more pronounced cavities.

From a practical standpoint, achieving consistent hole formation requires precision in both the cheesemaking and aging processes. The curd must be cut and stirred in a way that allows for even distribution of the bacteria while maintaining sufficient moisture to support their activity. During aging, the cheese should be kept at a stable temperature (around 20–24°C or 68–75°F) and high humidity to prevent the rind from drying out, which could restrict gas expansion. Cheesemakers may also use starter cultures with specific strains of *Propionibacterium* to ensure reliable hole formation. For home cheesemakers, experimenting with these bacteria and aging conditions can be a rewarding way to replicate the process, though it demands patience and attention to detail.

Comparatively, cheeses without these bacteria, such as Cheddar or Mozzarella, lack holes because their microbial cultures do not produce carbon dioxide in the same manner. This highlights the unique role of *Propionibacterium* in creating the iconic texture of Swiss-type cheeses. While some may view the holes as merely aesthetic, they also influence the cheese’s flavor and mouthfeel, contributing to its nutty, slightly sweet profile and open texture. Thus, hole formation is not just a visual trait but a key aspect of the cheese’s identity, rooted in the interplay of biology and craftsmanship.

Finally, for those curious about the science behind the holes, it’s worth noting that the process is a delicate balance of art and chemistry. Too much bacterial activity can lead to overly large or uneven holes, while too little results in a dense, hole-free cheese. Modern cheesemaking often employs controlled environments and microbial cultures to optimize this balance, ensuring consistency in both appearance and quality. Whether you’re a cheesemaker or simply a cheese enthusiast, understanding the role of carbon dioxide bubbles in hole formation adds a new layer of appreciation for this ancient craft.

Understanding American Cheese: Origins, Uses, and Cultural Significance

You may want to see also

Non-Swiss Cheeses: Gouda, Provolone, and some Cheddars can also have holes

While Swiss cheese is famously associated with holes, it’s a misconception that it holds a monopoly on this trait. Gouda, Provolone, and certain Cheddars can also develop holes during their aging process, though the reasons and appearances differ. For instance, Gouda’s holes are typically smaller and less uniform, often described as "eyes," and are a result of carbon dioxide gas released by bacteria during fermentation. These holes are more common in younger Goudas, aged 1 to 6 months, where the curd structure is less dense. Provolone, on the other hand, may exhibit larger, irregular holes, especially in its smoked varieties, due to the stretching and aging techniques used in its production. Cheddars, particularly those aged over 12 months, can develop tiny, scattered holes, though this is less common and often a sign of specific bacterial activity or handling during production.

To identify hole-bearing non-Swiss cheeses, consider the aging process and production method. Gouda aged under 6 months is more likely to have visible eyes, while older varieties tend to be denser. Provolone’s holes are often a byproduct of its pasta filata technique, where the cheese is stretched and kneaded, trapping air pockets. For Cheddar, look for artisanal or farmhouse varieties, as mass-produced versions rarely exhibit this trait. When selecting these cheeses, inspect the rind and interior for signs of gas pockets, which indicate the presence of holes. Pairing hole-bearing Gouda with fruits or nuts enhances its mild, nutty flavor, while Provolone’s smoky profile complements cured meats and robust wines.

If you’re a home cheesemaker, encouraging hole formation in Gouda or Cheddar requires precise control of humidity and temperature during aging. Maintain a consistent 50-55°F (10-13°C) and 85-90% humidity for optimal bacterial activity. For Provolone, focus on the stretching process; ensure the curd reaches 165-170°F (74-77°C) before shaping to create air pockets. Avoid over-pressing the cheese, as this can expel gas and prevent hole formation. Experimenting with starter cultures, such as those containing *Propionibacterium freudenreichii*, can also induce hole development, though this is more common in Swiss-style cheeses.

The presence of holes in non-Swiss cheeses isn’t a defect but a unique characteristic that reflects craftsmanship and aging conditions. While Swiss cheese holes are larger and more uniform due to specific bacterial activity, those in Gouda, Provolone, and Cheddar are subtler and tied to their distinct production methods. Appreciating these differences allows cheese enthusiasts to explore a broader range of flavors and textures. For instance, the small eyes in young Gouda add a creamy mouthfeel, while Provolone’s holes contribute to its chewy, smoky bite. By understanding these nuances, you can elevate your cheese board or recipe with varieties that defy the Swiss stereotype.

Finally, when serving hole-bearing non-Swiss cheeses, consider their texture and flavor profiles. Young Gouda with eyes pairs well with light crackers or fresh bread, allowing its mild sweetness to shine. Provolone’s holes make it ideal for melting, adding a unique texture to sandwiches or grilled dishes. Aged Cheddar with tiny holes offers a sharper, more complex flavor, perfect for standalone tasting or grating over dishes. By highlighting these cheeses’ distinct hole characteristics, you not only educate your palate but also challenge the notion that holes belong exclusively to Swiss varieties.

Is Halloumi Cheese Acidic? Uncovering Its pH Level and Health Impact

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Hole Size: Varies by cheese type, aging time, and production methods

The size of holes in cheese, often referred to as "eyes," is not a random occurrence but a result of specific conditions during the cheese-making process. For instance, Swiss cheese, particularly Emmental, is famous for its large, irregular holes, which are formed by carbon dioxide gas released by bacteria during aging. In contrast, cheeses like Gouda or Cheddar may have smaller, more uniform holes or none at all, depending on the production method and aging time. Understanding these factors allows cheese enthusiasts to predict and appreciate the texture and appearance of their favorite varieties.

To manipulate hole size in cheese production, consider the role of bacteria and aging time. Propionic acid bacteria, commonly used in Swiss-type cheeses, produce carbon dioxide gas as they metabolize lactic acid. The longer the cheese ages, the more gas is produced, leading to larger holes. For example, a young Emmental aged for 2-3 months may have smaller, less pronounced eyes, while a wheel aged for 6-12 months will exhibit the characteristic large, walnut-sized holes. Producers can control this by adjusting the bacteria culture dosage—typically 0.5-1% of the milk volume—and monitoring humidity and temperature during aging, ideally kept at 68-77°F (20-25°C) with 90-95% humidity.

A comparative analysis reveals that hole size is not just about aesthetics but also affects flavor and texture. Larger holes in cheeses like Appenzeller or Leerdammer create a lighter, airier mouthfeel, while smaller or absent holes in cheeses like Parmesan or Brie contribute to a denser, creamier texture. For home cheesemakers, experimenting with hole size can be a rewarding challenge. Start by using a mesophilic starter culture and adding propionic acid bacteria for larger holes. Age the cheese in a controlled environment, gradually increasing the duration to observe how hole size evolves. Be cautious, however, as excessive gas production can cause the cheese to crack or develop an undesirable texture.

From a practical standpoint, hole size can also indicate the quality and authenticity of certain cheeses. For example, traditional Emmental should have holes ranging from cherry to walnut size, evenly distributed throughout the cheese. If the holes are too small, too large, or uneven, it may suggest improper aging or the use of non-traditional methods. When selecting cheese, consider the hole size as a clue to its flavor profile—larger holes often correlate with a nutty, complex flavor, while smaller holes may indicate a milder, smoother taste. This knowledge empowers consumers to make informed choices and appreciate the craftsmanship behind each wheel.

Smoky Italian Delight: Exploring Semi-Hard Smoked Cheese Varieties

You may want to see also

Myth Debunked: Not all Swiss cheeses have holes; it depends on the variety

Swiss cheese is often synonymous with holes, but this iconic image doesn’t apply to all varieties. Take Emmental, for instance, a Swiss cheese famous for its large, irregular holes caused by carbon dioxide bubbles released during fermentation. However, other Swiss cheeses like Appenzeller or Gruyère lack these holes entirely. The presence of holes depends on the specific production methods, bacterial cultures, and aging processes unique to each variety. This diversity challenges the blanket assumption that all Swiss cheeses share the same structural characteristic.

To understand why some Swiss cheeses have holes while others don’t, consider the role of *Propionibacterium freudenreichii*, a bacterium introduced during cheesemaking. This bacterium produces carbon dioxide gas, which becomes trapped in the curd, forming holes. In cheeses like Emmental, this process is encouraged through specific aging conditions and larger curd sizes. Conversely, cheeses like Sbrinz or Tilsit, also Swiss in origin, are made with smaller curds or different bacterial cultures, resulting in a dense, hole-free texture. The takeaway? Hole formation is a deliberate outcome of specific techniques, not a universal trait of Swiss cheeses.

If you’re selecting a Swiss cheese for a recipe, knowing the variety matters. For example, Emmental’s holes make it ideal for melting in dishes like fondue or quiche, where its texture adds visual appeal. In contrast, Gruyère’s smooth, hole-free structure is better suited for gratins or sandwiches, where even melting is key. Practical tip: Always check the cheese’s variety label to ensure it aligns with your culinary needs. Assuming all Swiss cheeses behave the same could lead to unexpected results in your cooking.

Finally, debunking this myth highlights the importance of appreciating cheese diversity. Swiss cheeses are not a monolithic category but a spectrum of flavors, textures, and structures. By understanding the nuances of each variety, you can make informed choices, whether for cooking, pairing, or simply enjoying cheese on its own. Next time you encounter a Swiss cheese, remember: the holes are just one part of its story, not the entire narrative.

Secrets to Keeping Velveeta Cheese Dip Smooth and Creamy

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Swiss cheese, particularly Emmental, is famous for its distinctive holes.

The holes, called "eyes," are formed by carbon dioxide gas released by bacteria during the aging process.

No, the holes in Swiss cheese are natural and safe to eat; they are part of the cheese's unique character.

Not all Swiss cheeses have holes; only certain varieties like Emmental and Appenzeller are known for this feature.

Yes, some other cheeses like Gouda or Provolone can occasionally develop small holes due to similar bacterial activity.