The chemical that prevents fat from leaching out of cheese is sodium citrate, a salt derived from citric acid. Commonly used in processed cheese products, sodium citrate acts as an emulsifying agent, binding fat and water molecules together to create a smooth, consistent texture. This property not only keeps the fat evenly distributed but also enhances the cheese's meltability, making it a key ingredient in dishes like nachos, cheese sauces, and grilled cheese sandwiches. Its ability to stabilize fat ensures that cheese retains its creamy mouthfeel and appearance, even when heated or processed.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

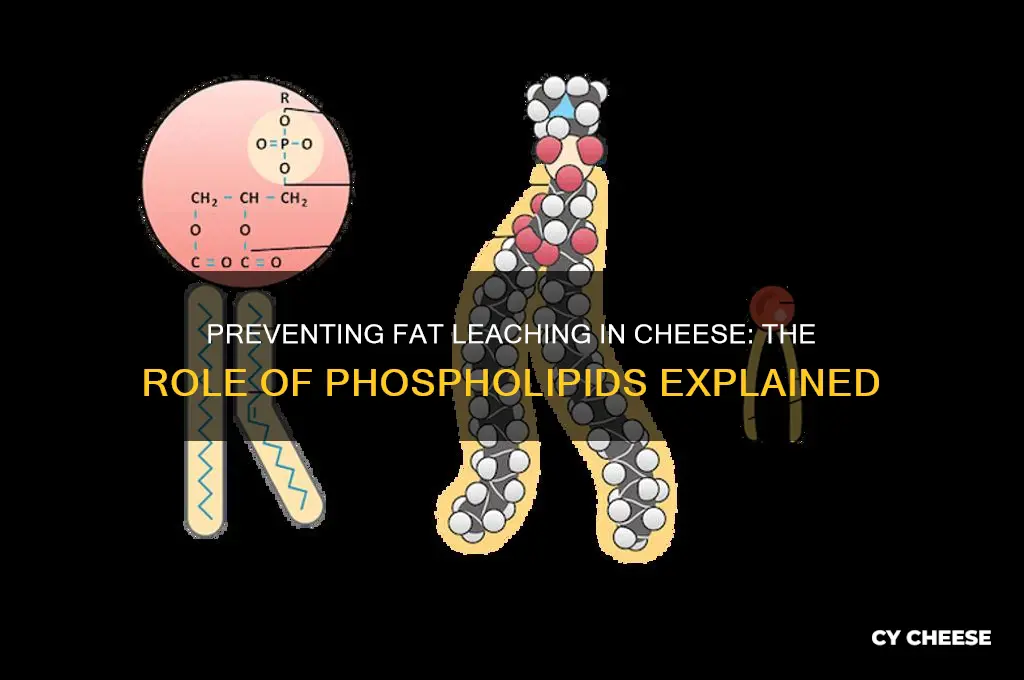

Role of Phospholipids in Cheese

Phospholipids are the unsung heroes in the complex chemistry of cheese, acting as critical emulsifiers that prevent fat from leaching out during production and aging. These molecules, with their hydrophilic head and hydrophobic tails, form a stable interface between water and fat, ensuring the cheese’s texture remains consistent. Without phospholipids, cheese would lose its creamy mouthfeel, becoming greasy or dry, depending on the type. Their role is particularly vital in high-fat cheeses like cheddar or gouda, where fat retention directly impacts flavor and structure.

Consider the process of cheese making: milk is curdled, and the solids are separated from whey. During this phase, phospholipids naturally present in milk align themselves around fat globules, creating a protective barrier. This barrier prevents fat from escaping into the whey, ensuring it remains integrated into the cheese matrix. For example, in cheddar cheese, phospholipids help maintain the smooth, sliceable texture by keeping fat evenly distributed. Manufacturers often add supplemental phospholipids, such as lecithin, to enhance this effect, especially in low-fat or processed cheeses where natural levels are insufficient.

The effectiveness of phospholipids depends on their concentration and the cheese-making conditions. Studies show that a phospholipid concentration of 0.5–1.0% relative to milk fat is optimal for most cheeses. However, temperature and pH play a role—at higher temperatures, phospholipids can degrade, reducing their emulsifying capacity. For home cheese makers, ensuring milk is not overheated during curdling is crucial to preserving these molecules. Additionally, using fresh milk with intact phospholipids yields better results than ultra-pasteurized milk, which often lacks these compounds.

From a practical standpoint, understanding phospholipids can help troubleshoot common cheese-making issues. If your cheese is exuding oil (a condition called "fat blow"), it may indicate insufficient phospholipids or improper handling during production. To mitigate this, consider adding a small amount of soy or sunflower lecithin (1–2 grams per liter of milk) during the mixing stage. For aged cheeses, monitoring humidity and temperature during ripening is essential, as fluctuations can disrupt the phospholipid barrier, leading to fat separation.

In conclusion, phospholipids are not just passive components in cheese but active agents that dictate its quality and longevity. Their ability to stabilize fat-water interactions is indispensable, whether in artisanal or industrial cheese production. By recognizing their role and adjusting processes accordingly, cheese makers can ensure a superior product that retains its fat content, texture, and flavor. Next time you enjoy a slice of cheese, remember the silent work of phospholipids behind its perfection.

Unveiling the Age of the World's Oldest Piece of Cheese

You may want to see also

Effect of Emulsifiers on Fat Retention

Emulsifiers play a pivotal role in cheese manufacturing by stabilizing fat droplets, preventing them from coalescing or separating during processing and storage. These compounds, such as mono- and diglycerides (E471), lecithin, and polysorbates, act at the oil-water interface, reducing interfacial tension and creating a stable emulsion. In cheese, where fat is dispersed in a protein matrix, emulsifiers ensure that fat remains uniformly distributed, minimizing leaching during aging or melting. For instance, adding 0.1–0.3% mono- and diglycerides by weight to cheese formulations has been shown to significantly enhance fat retention, particularly in low-moisture cheeses like cheddar.

The effectiveness of emulsifiers in fat retention depends on their chemical structure and dosage. Hydrophilic-lipophilic balance (HLB) values are critical; emulsifiers with HLB values between 4 and 8 are ideal for stabilizing fat in cheese, as they balance affinity for both aqueous and lipid phases. Overuse, however, can lead to undesirable textures or off-flavors. For example, exceeding 0.5% emulsifier concentration in mozzarella cheese can result in a gummy mouthfeel. Manufacturers must therefore calibrate dosage to achieve optimal fat retention without compromising sensory qualities.

Comparatively, natural emulsifiers like lecithin offer a cleaner label alternative to synthetic options, appealing to health-conscious consumers. Derived from sources such as soybeans or sunflower seeds, lecithin is effective at doses of 0.2–0.4% in cheese production. While slightly less efficient than mono- and diglycerides, its natural origin often justifies the trade-off. In contrast, synthetic emulsifiers like polysorbates are more potent but may face regulatory scrutiny in certain markets, limiting their applicability.

Practical implementation requires careful consideration of processing conditions. Emulsifiers should be added during the mixing or kneading stage of cheese production to ensure even distribution. For aged cheeses, emulsifiers must remain stable over extended periods, resisting degradation from enzymes or microbial activity. Regular quality control checks, such as fat separation analysis, can verify their efficacy. Additionally, pairing emulsifiers with stabilizers like carrageenan or alginates can further enhance fat retention, particularly in processed cheese products.

In conclusion, emulsifiers are indispensable tools for maintaining fat integrity in cheese, with their selection and application requiring precision. By understanding their mechanisms, optimal dosages, and interactions with other ingredients, manufacturers can achieve consistent product quality while meeting consumer demands for texture and stability. Whether opting for synthetic efficiency or natural appeal, the strategic use of emulsifiers ensures that fat remains where it belongs—evenly dispersed within the cheese matrix.

Master Mario Kart 8 Deluxe: Secret Cheese Strategies for Easy Wins

You may want to see also

Impact of Protein Matrix on Fat Stability

The protein matrix in cheese acts as a scaffold, trapping fat globules and preventing them from leaching out during processing or storage. This phenomenon is crucial for maintaining texture, flavor, and nutritional value. Proteins like casein form a complex network that binds fat, creating a stable emulsion. Without this matrix, fat would separate, leading to greasy cheese with poor sensory qualities. Understanding this interaction is key to optimizing cheese production and extending shelf life.

Consider the role of heat-induced protein coagulation in fat retention. During cheese making, heat denatures casein proteins, causing them to aggregate and encapsulate fat globules. For instance, in cheddar cheese, the curd is heated to 39–42°C (102–108°F) to promote protein matrix formation. This step is critical; insufficient heating results in weak matrices that fail to hold fat, while excessive heat can lead to protein over-coagulation, making the cheese rubbery. Precision in temperature control ensures optimal fat stability without compromising texture.

From a practical standpoint, manufacturers can enhance fat retention by adjusting protein-to-fat ratios. A higher protein content strengthens the matrix, reducing fat exudation. For example, adding 0.5–1.0% non-fat dry milk solids during processing increases protein availability, improving fat binding. However, this must be balanced with cost and desired product characteristics. Over-fortification can alter flavor and increase production expenses. Regular testing of protein levels and fat retention rates ensures consistency in the final product.

Comparatively, the protein matrix’s impact on fat stability differs across cheese varieties. Hard cheeses like Parmesan have a denser protein network, effectively immobilizing fat for years. In contrast, soft cheeses like Brie have a looser matrix, allowing controlled fat release for a creamy texture. Producers can tailor matrix properties by adjusting pH, salt concentration, and enzyme activity. For instance, lowering pH during coagulation tightens protein bonds, enhancing fat retention in semi-hard cheeses like Gouda.

Finally, innovations in protein engineering offer new avenues for improving fat stability. Enzymes like transglutaminase can cross-link proteins, creating stronger matrices that resist fat leaching. Studies show that adding 0.1–0.2% transglutaminase to cheese milk increases fat retention by up to 20%. However, regulatory approvals and consumer acceptance must be considered. Combining traditional methods with modern techniques allows producers to meet demands for stable, high-quality cheese products.

Does Munster Cheese Originate from Ireland's Munster Province?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Function of Citrates in Cheese Production

Citrates, specifically sodium citrate and potassium citrate, play a pivotal role in cheese production by stabilizing fat emulsions, preventing fat separation, and ensuring a smooth, consistent texture. These compounds act as sequestrants, binding calcium ions that would otherwise cause fat globules to coalesce and rise to the surface during processing. In cheeses like cheddar or mozzarella, citrates are often added at a dosage of 0.1% to 0.3% of the milk weight, depending on the desired texture and fat content. This precise application ensures the fat remains evenly distributed, enhancing both appearance and mouthfeel.

From a practical standpoint, citrates are particularly useful in high-fat cheeses or those subjected to heat treatment, such as pasteurized process cheese. Without citrates, heat-induced calcium release can destabilize the fat emulsion, leading to greasy textures or oiling off. For home cheesemakers, incorporating citrates requires careful measurement and timing. Add the citrate solution during the initial stages of curdling, ensuring thorough mixing to avoid localized clumping. Commercial producers often use pre-blended citrate mixes, which include additional stabilizers like carrageenan for added consistency.

A comparative analysis highlights the advantage of citrates over traditional methods like pH adjustment with acids. While acids can improve emulsification, they risk over-acidifying the cheese, affecting flavor and curd formation. Citrates, being milder, maintain pH balance while effectively chelating calcium ions. This dual functionality makes them indispensable in large-scale production, where consistency and efficiency are paramount. For artisanal cheesemakers, citrates offer a way to replicate industrial-grade textures without compromising on natural ingredients.

Finally, the use of citrates extends beyond texture stabilization. They contribute to shelf life by inhibiting fat migration, which can cause surface discoloration or off-flavors. In low-moisture cheeses like cheddar, citrates help retain moisture by preventing fat from separating and creating dry pockets. However, overuse can lead to a slippery texture or metallic aftertaste, so adherence to recommended dosages is critical. For producers aiming for organic certification, potassium citrate is often preferred over sodium citrate due to its perceived natural alignment, though both are generally recognized as safe (GRAS) by regulatory bodies.

In summary, citrates are a versatile and essential tool in cheese production, offering fat stabilization, texture enhancement, and shelf-life extension. Their application requires precision but rewards producers with consistent, high-quality results. Whether in industrial settings or home kitchens, understanding and leveraging citrates can elevate the craft of cheesemaking.

Does Port Wine Cheese Contain Alcohol? Uncovering the Truth Behind the Name

You may want to see also

Role of Salt in Fat Binding

Salt, specifically sodium chloride (NaCl), plays a pivotal role in cheese production by preventing fat from leaching out during aging and storage. Its effectiveness stems from its ability to interact with both the protein matrix and the moisture content of cheese. When added during the curdling process, salt disrupts the hydration layer around casein proteins, causing them to tighten and form a denser network. This structural change traps fat globules within the matrix, reducing their mobility and preventing them from migrating to the surface. For example, in cheddar cheese, a salt concentration of 1.5–2.0% by weight is typically used to achieve optimal fat retention while maintaining flavor balance.

The mechanism of salt’s fat-binding action can be understood through its osmotic effect. As salt diffuses into the cheese curd, it draws moisture out of the protein matrix, concentrating the proteins and reducing free water available for fat separation. This dehydration process is particularly critical in semi-hard and hard cheeses, where fat leakage can compromise texture and appearance. Studies show that a 10% reduction in moisture content, facilitated by proper salting, can increase fat retention by up to 25%. However, excessive salt can lead to a dry, crumbly texture, so precision in dosage is essential.

Practical application of salt in cheese making requires careful timing and technique. For artisanal producers, brine immersion is a common method, where cheese is soaked in a saturated salt solution (26–28° Brix) for 12–24 hours. Industrial processes often use dry salting, where salt is mixed directly into the curd, followed by pressing to ensure even distribution. A key caution is to avoid over-salting, as this can inhibit lactic acid bacteria activity, affecting flavor development. Monitoring pH levels during salting (targeting a pH of 5.2–5.4) ensures the process supports both fat binding and microbial activity.

Comparatively, salt’s role in fat binding is more pronounced in cheeses with higher fat content, such as Gouda or Swiss, where fat globules are more prone to migration. In contrast, fresh cheeses like mozzarella rely less on salt for fat retention due to their shorter aging periods and higher moisture content. This highlights the need to tailor salt usage to the specific cheese variety. For home cheese makers, starting with a 2% salt-to-cheese weight ratio and adjusting based on sensory evaluation is a reliable approach.

In conclusion, salt’s dual action—structurally tightening the protein matrix and reducing free moisture—makes it indispensable for preventing fat leaching in cheese. Its application demands precision, balancing fat retention with texture and flavor development. By understanding its mechanisms and adapting techniques to cheese type, producers can ensure a product that is both visually appealing and culinarily satisfying. Whether in a small-scale kitchen or a large factory, mastering salt’s role in fat binding is key to crafting high-quality cheese.

Should You Eat Brie Rind? A Guide to Enjoying Brie Cheese

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The chemical primarily responsible for preventing fat from leaching from cheese is calcium phosphate, which helps stabilize the fat globules within the cheese matrix.

Calcium phosphate acts as an emulsifying agent, binding fat globules to the protein network in cheese, which keeps the fat from separating or leaching out.

Yes, sodium citrate and carrageenan are also used in some processed cheeses to stabilize fat and prevent leaching by improving the emulsion between fat and water.

Yes, chemicals like calcium phosphate, sodium citrate, and carrageenan are generally recognized as safe (GRAS) by regulatory agencies when used in approved amounts in food products.

Natural cheese relies on its own proteins and calcium phosphate to stabilize fat, while processed cheese often uses additional emulsifiers like sodium citrate or carrageenan to prevent fat leaching.