Natural cheese comes in a variety of colors, ranging from pale white to deep yellow, depending on factors such as the type of milk used, the diet of the animals producing the milk, and the aging process. For instance, cheeses made from cow's milk often have a pale yellow hue due to the presence of carotene, a natural pigment found in grass. However, cheeses made from goat or sheep's milk tend to be whiter, as these animals' milk contains less carotene. Additionally, some cheeses may have their color altered through the addition of annatto, a natural dye derived from the seeds of the achiote tree, which gives them a more pronounced yellow or orange tint. Understanding these factors helps explain the diverse colors found in natural cheeses.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Color Range | Pale yellow to deep gold, ivory, white, orange, brown, or even blue (due to mold) |

| Factors Influencing Color | Milk source (cow, goat, sheep), animal diet, aging process, added bacteria/mold, natural pigments (e.g., annatto) |

| Common Natural Colors | Pale yellow (Cheddar, Swiss), ivory/white (Mozzarella, Feta), orange (naturally colored Cheddar, Mimolette), blue (Blue Cheese), brown (aged cheeses like Gruyère) |

| Artificial Color Absence | Natural cheese does not contain artificial dyes; any color comes from natural sources or processes |

| Exceptions | Some cheeses may have added annatto (natural plant-based dye) for a more pronounced orange hue, but this is still considered natural |

| Texture and Color Correlation | No direct correlation; color does not determine texture (e.g., soft white Brie vs. hard pale yellow Parmesan) |

| Flavor and Color Correlation | Limited correlation; color may hint at aging (deeper colors often mean longer aging), but flavor is influenced by many other factors |

| Examples of Natural Colors | Cheddar (pale yellow to orange), Mozzarella (ivory/white), Blue Cheese (white with blue veins), Mimolette (bright orange), Gruyère (pale yellow to brown) |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Milk Source Impact: Cow, goat, or sheep milk affects cheese color due to natural pigments

- Aging Effects: Longer aging darkens cheese, creating deeper hues like in Parmesan

- Feed Influence: Animal diet alters milk color, impacting cheese appearance subtly

- Natural Additives: Annatto or paprika are used to enhance or modify cheese color

- Regional Variations: Local practices and traditions influence natural cheese color globally

Milk Source Impact: Cow, goat, or sheep milk affects cheese color due to natural pigments

Natural cheese color varies significantly based on the milk source, a fact rooted in the unique composition of cow, goat, and sheep milk. Each type of milk contains distinct levels of carotene, a natural pigment responsible for yellow and orange hues. Cow’s milk, for instance, typically has higher carotene levels compared to goat or sheep milk, which is why cheeses like Cheddar or Gouda often exhibit deeper yellow tones. This variation isn’t arbitrary—it’s a direct reflection of the animal’s diet and genetics, making milk source a primary determinant of cheese color.

To understand this impact, consider the carotene content in different milks. Cow’s milk averages 0.05–0.1 mg of carotene per 100 grams, while goat’s milk contains roughly half that amount, and sheep’s milk falls in between. These differences translate directly to cheese color: a young goat cheese like Chèvre will often appear pale or nearly white due to lower carotene, whereas a sheep’s milk cheese like Manchego may show a softer yellow hue. Aging further intensifies color, as carotene concentrates over time, but the baseline pigment from the milk remains the foundation.

Practical tip: If you’re crafting cheese at home, choose your milk source deliberately to control color. For a pale, delicate cheese, opt for goat’s milk. For richer, golden tones, cow’s milk is ideal. Sheep’s milk offers a middle ground, perfect for cheeses with subtle warmth. Remember, additives like annatto (a natural dye) can enhance color, but the natural pigments in the milk set the stage.

Comparatively, the milk source also influences texture and flavor, but its role in color is both immediate and measurable. For example, a side-by-side comparison of fresh cheeses made from cow, goat, and sheep milk will reveal distinct color gradients, even before aging. This makes milk selection a critical step for cheesemakers aiming for specific visual outcomes. By prioritizing natural pigments, you ensure authenticity and consistency in your cheese’s appearance.

In conclusion, the milk source isn’t just a flavor choice—it’s a color choice. Cow, goat, and sheep milk each bring unique carotene levels to the table, directly shaping the hue of the cheese. Whether you’re a cheesemaker or a connoisseur, understanding this relationship allows you to predict and manipulate color with precision, ensuring your cheese not only tastes exceptional but looks the part too.

Discover Skeeter's Roof Aged Cheese: Locations and Tasting Tips

You may want to see also

Aging Effects: Longer aging darkens cheese, creating deeper hues like in Parmesan

Natural cheese, in its freshest state, often presents a palette of pale ivory to soft yellow, a result of the milk’s inherent pigments and the minimal processing involved. However, as cheese ages, a transformation occurs, deepening its color and intensifying its flavor. This phenomenon is particularly evident in hard cheeses like Parmesan, where extended aging—often 12 to 36 months—results in a rich, golden-brown hue. The science behind this lies in the breakdown of proteins and fats, which releases compounds that darken the cheese over time. For those seeking to replicate this effect, understanding the aging process is key: controlled humidity (around 80-85%) and temperature (50-54°F) are critical factors in achieving the desired color and texture.

The aging process isn’t merely a cosmetic change; it’s a complex interplay of chemistry and microbiology. As cheese matures, enzymes and bacteria break down lactose and proteins, creating amino acids and other compounds that contribute to its darker appearance. For example, tyrosine, an amino acid present in milk, oxidizes during aging, leading to the browning effect seen in aged cheeses. This is why younger cheeses like fresh mozzarella retain their pale color, while older varieties like Gruyère or Gouda develop deeper, more amber tones. To accelerate this process, some cheesemakers introduce specific bacteria cultures or adjust pH levels, though patience remains the most critical ingredient.

For home cheesemakers or enthusiasts, experimenting with aging can yield fascinating results. Start by selecting a hard cheese variety, such as a young Grana Padano, and age it in a dedicated refrigerator set to the optimal conditions mentioned earlier. Monitor the cheese weekly, noting changes in color, texture, and flavor. A practical tip: wrap the cheese in cheesecloth or waxed paper to allow breathability while preventing excessive moisture loss. Over time, you’ll observe the gradual darkening, a visual cue that the cheese is developing its signature complexity. Remember, longer aging not only deepens the color but also enhances the umami and nutty notes, making the wait worthwhile.

Comparatively, the aging effect on cheese color highlights the contrast between fresh and mature varieties, offering a sensory journey from light to dark, mild to robust. While soft cheeses like Brie or Camembert may develop a bloomy rind, their interiors remain relatively pale due to shorter aging periods. In contrast, the deep, caramelized tones of a well-aged Parmesan or Pecorino are a testament to the transformative power of time. This visual evolution is not just a marker of age but a promise of richer flavors and a more crystalline texture, rewarding those who appreciate the art of slow fermentation.

In conclusion, the darkening of cheese through aging is both a science and an art, a process that rewards patience with deeper hues and more complex flavors. Whether you’re a cheesemaker or a connoisseur, understanding this phenomenon allows you to appreciate the craftsmanship behind every wheel or wedge. By controlling aging conditions and observing the gradual changes, you can unlock the full potential of natural cheese, turning it from a simple ingredient into a masterpiece of culinary tradition.

Does Cheese Contain BCAAs? Unlocking the Protein Power in Dairy

You may want to see also

Feed Influence: Animal diet alters milk color, impacting cheese appearance subtly

Natural cheese hues, often assumed to be uniform, are subtly shaped by the diet of the animals producing the milk. This phenomenon, known as feed influence, highlights how what cows, goats, or sheep consume directly affects the color of their milk and, consequently, the cheese made from it. For instance, grazing on fresh green pastures rich in beta-carotene imparts a golden or creamy tint to milk, which translates into warmer, richer tones in cheeses like Cheddar or Gruyère. Conversely, animals fed on hay or silage, lower in carotenoids, produce milk with a paler, almost ivory appearance, resulting in cheeses like fresh mozzarella or chèvre with cooler, whiter shades.

To harness feed influence intentionally, farmers can adjust animal diets with specific forage types or supplements. For example, incorporating 1–2 kg of carotene-rich feed daily, such as dried alfalfa or marigold petals, can deepen milk’s yellow hue within 2–3 weeks. However, caution is necessary: excessive supplementation may lead to an unnatural, overly orange cheese, detracting from its perceived authenticity. Similarly, grazing animals on diverse pastures with wildflowers or herbs not only enhances milk color but also introduces subtle flavor nuances, creating a multi-sensory experience in the final product.

The impact of feed influence extends beyond aesthetics, intersecting with consumer perceptions of naturalness and quality. A study by the Journal of Dairy Science found that cheeses with golden hues, indicative of pasture-fed animals, were perceived as more "natural" and higher in quality by 72% of participants. This underscores the importance of transparency in labeling, such as "pasture-raised" or "grass-fed," to align consumer expectations with the subtle color variations resulting from feed influence.

Practical tips for cheesemakers and consumers alike include observing seasonal shifts in cheese color, as milk from spring and summer grazing tends to be richer in carotenoids compared to winter diets. For home enthusiasts experimenting with raw milk cheeses, sourcing milk from farms with known forage practices can yield more consistent results. Ultimately, understanding feed influence transforms cheese color from a passive trait to an intentional expression of animal husbandry and terroir, enriching both the craft and appreciation of natural cheese.

Prevent Cheese Burn: Easy Tips for Perfect Pan Melting

You may want to see also

Explore related products

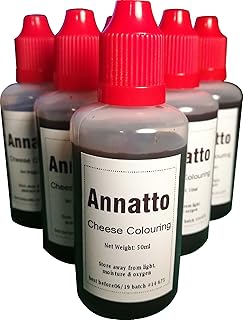

Natural Additives: Annatto or paprika are used to enhance or modify cheese color

Natural cheese, in its unadulterated form, often ranges from pale yellow to ivory, depending on the diet of the milk-producing animals and the cheese-making process. However, consumers frequently associate richer, deeper hues with quality and flavor, a perception that has driven the use of natural additives like annatto and paprika. These plant-based colorants are not merely cosmetic; they serve as a nod to tradition, a tool for differentiation, and a means to meet market expectations. Annatto, derived from the seeds of the achiote tree, imparts a yellow-to-orange spectrum, while paprika, made from ground peppers, offers shades from warm red to deep orange. Both are FDA-approved, making them staples in the cheese industry for their safety and efficacy.

When incorporating annatto or paprika into cheese, precision is key. Dosage typically ranges from 0.01% to 0.05% of the total cheese weight, depending on the desired intensity. For example, a 10-pound batch of cheddar might use 0.1 to 0.5 ounces of annatto extract. The additive is often dissolved in a small amount of warm water or oil before being mixed into the milk or curd. Paprika, being less potent, may require slightly higher quantities. Timing matters too: adding the colorant during the curdling stage ensures even distribution, whereas late addition can result in streaking. Always test small batches to calibrate color accuracy before scaling up production.

The choice between annatto and paprika often hinges on the desired outcome and the cheese variety. Annatto is the go-to for mimicking the golden hue of grass-fed cow’s milk cheeses, such as cheddar or Colby. Its earthy undertones complement the nuttiness of aged cheeses without overpowering their natural flavor profiles. Paprika, on the other hand, is ideal for creating vibrant orange or red shades in cheeses like Gouda or Cheshire. Its subtle heat can enhance the complexity of smoked or spiced varieties. For artisanal producers, combining both additives in precise ratios allows for customization, enabling them to craft unique color signatures that align with their brand identity.

While natural additives offer aesthetic and marketing advantages, they are not without considerations. Annatto, though rare, can cause allergic reactions in sensitive individuals, manifesting as skin rashes or digestive discomfort. Paprika, being a pepper derivative, may introduce mild spiciness, which could be undesirable in milder cheeses. Additionally, over-reliance on colorants can mislead consumers about the cheese’s natural qualities. Transparency is crucial; clearly labeling the use of annatto or paprika builds trust and ensures compliance with regulatory standards. When used thoughtfully, these additives enhance cheese without compromising its integrity, striking a balance between tradition and innovation.

Proper Yak Cheese Storage: Tips for Preserving Flavor and Freshness

You may want to see also

Regional Variations: Local practices and traditions influence natural cheese color globally

Natural cheese colors vary widely across regions, shaped by local practices and traditions that have evolved over centuries. In France, for example, the pale ivory hue of Brie and Camembert is a result of specific Penicillium camemberti molds and the use of raw cow’s milk, combined with a humid aging environment. This contrasts sharply with the deep golden rind of Mimolette from Lille, achieved through the addition of annatto, a natural dye derived from the achiote tree, a practice rooted in 17th-century Dutch influence. These examples illustrate how regional techniques and cultural preferences directly dictate the visual identity of cheese.

In the Mediterranean, sheep’s milk cheeses like Pecorino Romano from Italy or Manchego from Spain often exhibit a natural pale yellow to straw color due to the carotene content in the milk of grass-fed sheep. The firmness and texture of these cheeses are further enhanced by longer aging periods, which deepen their color slightly. Meanwhile, in the Balkans, cheeses like Serbian Kajmak or Bulgarian Sirene are typically stark white, reflecting the use of cow’s or sheep’s milk and a focus on preserving freshness and creaminess. These variations highlight how geography, animal diet, and production methods converge to create distinct regional profiles.

Northern European cheeses, such as Norwegian Brunost or Dutch Gouda, showcase unique colorations tied to local traditions. Brunost, also known as "brown cheese," derives its deep caramel hue from the boiling of whey, cream, and milk until the sugars caramelize, a process unique to Scandinavian dairy practices. Gouda, on the other hand, ranges from pale yellow to red-orange depending on the addition of annatto, a tradition adopted to mimic the appearance of higher-fat cheeses. These practices demonstrate how cultural innovation and historical trade routes influence cheese aesthetics.

In the Americas, regional cheeses like Mexican Queso Oaxaca or Brazilian Queijo Coalho exhibit colors tied to local ingredients and techniques. Oaxaca cheese, a stringy, pale white cheese, is made by stretching fresh curds in a process similar to mozzarella, reflecting indigenous and Spanish colonial influences. Queijo Coalho, a golden-hued cheese from Brazil, owes its color to the milk of free-range cows and the use of annatto, a practice adapted from Portuguese settlers. These examples underscore how colonization, indigenous knowledge, and available resources shape cheese coloration across continents.

Understanding these regional variations not only enriches appreciation for natural cheese but also guides practical applications. For instance, when pairing cheese with wine or creating a cheese board, consider the cultural context behind each cheese’s color to enhance thematic coherence. Additionally, home cheesemakers can experiment with traditional techniques, such as using annatto or specific molds, to replicate regional styles. By embracing these practices, one can explore the global tapestry of cheese while honoring the traditions that define it.

Master the Art of Pickling Cheese: Easy Steps for Delicious Results

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Natural cheese can vary in color depending on the type, but it is typically white, ivory, pale yellow, or cream-colored. The color comes from the milk and natural aging process, without added dyes.

Some natural cheese appears yellow due to the presence of carotene, a pigment found in the milk of grass-fed cows. Harder cheeses like Cheddar often have a deeper yellow hue from this natural coloring.

Natural cheese is not typically orange. Orange cheese is usually colored artificially with annatto, a natural dye derived from the achiote tree. This practice is common in cheeses like American Cheddar but is not a natural color.