Making cheese at home is an accessible and rewarding craft that requires a few essential tools and ingredients. To begin, you’ll need high-quality milk, preferably raw or pasteurized but not ultra-pasteurized, as it serves as the base for your cheese. Key ingredients include rennet (or a vegetarian alternative) to coagulate the milk and starter cultures to develop flavor and acidity. Basic equipment includes a large pot, thermometer, cheesecloth, and a long knife for cutting the curds. Optional but helpful tools are a cheese press for harder varieties and pH strips to monitor acidity. With these supplies and a bit of patience, you can start crafting delicious homemade cheese.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Milk | Raw or pasteurized milk (cow, goat, sheep, or other dairy animals) |

| Coagulant | Rennet (animal or microbial), vinegar, lemon juice, or other acidifiers |

| Culture | Starter cultures (mesophilic or thermophilic bacteria) for flavor and acidity |

| Salt | Non-iodized salt for flavor and preservation |

| Equipment | Stainless steel or food-grade plastic pots, thermometer, long knife, cheesecloth, cheese press (optional), molds |

| Space | Clean, temperature-controlled environment (e.g., kitchen or dedicated cheese-making area) |

| Time | Patience for aging (varies from hours to years depending on cheese type) |

| Recipes | Specific instructions for the type of cheese you want to make (e.g., mozzarella, cheddar, feta) |

| Sanitization | Clean and sanitized tools and workspace to prevent contamination |

| Optional Tools | pH meter, curd knife, draining mats, wax for aging |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Basic Equipment: Pots, thermometer, cheesecloth, molds, and a long knife are essential tools for beginners

- Milk Selection: Choose raw, pasteurized, or homogenized milk based on the cheese type you plan to make

- Coagulants: Rennet, vinegar, or lemon juice are needed to curdle milk and start the cheese-making process

- Starter Cultures: Bacteria cultures help acidify milk and develop flavor in specific cheese varieties

- Sanitization: Clean and sterilize all equipment to prevent contamination and ensure safe cheese production

Basic Equipment: Pots, thermometer, cheesecloth, molds, and a long knife are essential tools for beginners

Cheese making, like any craft, requires the right tools to transform simple ingredients into a delicious final product. For beginners, the essential equipment list is surprisingly short but crucial. Let’s break it down: pots, a thermometer, cheesecloth, molds, and a long knife. These items form the backbone of your cheese-making setup, each serving a specific purpose in the process. Without them, you’ll find yourself improvising—and improvisation in cheese making often leads to inconsistency or failure.

Pots are your workhorse. You’ll need at least two: one large enough to heat milk (stainless steel is ideal for even heat distribution) and another for preparing cultures or rennet solutions. Avoid aluminum or cast iron, as they can react with acids in the milk, altering the flavor. A 6- to 8-quart pot is a good starting size for small batches, but consider larger if you plan to scale up. Always ensure your pot is clean and free of soap residue, as even trace amounts can interfere with curdling.

A thermometer is non-negotiable. Cheese making is a science, and precise temperature control is critical for curd formation and texture. Digital thermometers with clips are ideal, as they allow you to monitor the milk’s temperature hands-free. Aim for a thermometer that reads within ±1°F for accuracy. Overheating milk by just a few degrees can ruin a batch, so invest in a reliable tool. Calibrate it regularly to ensure consistency.

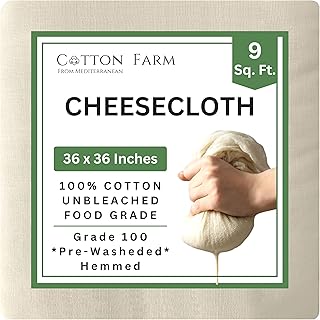

Cheesecloth is your filter. This fine, breathable fabric separates curds from whey, a step in nearly every cheese recipe. Opt for 100% cotton, unbleached cheesecloth, as synthetic materials can leave fibers in your cheese. For harder cheeses, you’ll need a tighter weave; for soft cheeses, a looser weave works fine. Always rinse cheesecloth in cold water before use to remove any lint or residue. Pro tip: double-layer the cloth for better filtration and durability.

Molds give your cheese its shape. Beginners should start with simple, perforated molds that allow whey to drain while holding the curds together. Plastic or food-grade polypropylene molds are affordable and easy to clean. For soft cheeses like ricotta, a basic mold with large holes is sufficient. For harder cheeses, consider a mold with a follower (a weighted lid) to press out excess whey. Avoid wooden molds unless they’re properly sealed, as they can absorb moisture and harbor bacteria.

Finally, a long knife is essential for cutting curds. This step, known as "cutting the curd," releases whey and determines the texture of your cheese. A thin, flexible blade (like a cake frosting spatula or a specialized cheese knife) works best, as it allows you to slice through curds without breaking them. Avoid serrated knives, which can tear the curds and release too much whey. Practice gentle, even strokes to achieve the desired curd size, typically between 1/4 to 1/2 inch.

Together, these tools form the foundation of your cheese-making journey. While the process may seem intricate, having the right equipment simplifies it, allowing you to focus on mastering techniques and experimenting with flavors. Start small, invest in quality tools, and soon you’ll be crafting cheeses that rival those from the dairy aisle.

Does Priano Cheese Tortellini Require Refrigeration? Storage Tips Revealed

You may want to see also

Milk Selection: Choose raw, pasteurized, or homogenized milk based on the cheese type you plan to make

The milk you choose is the foundation of your cheese, and its characteristics will profoundly influence the final product. Raw milk, with its intact enzymes and bacteria, offers a complex flavor profile and is ideal for traditional, artisanal cheeses like Camembert or Cheddar. However, it requires meticulous handling to avoid contamination. Pasteurized milk, heated to kill pathogens, is a safer option but may lack the depth of raw milk. Homogenized milk, with its fat globules broken down, can affect texture, often resulting in softer cheeses. Understanding these differences is crucial for achieving the desired taste and consistency.

Consider the cheese type as your starting point. For aged, hard cheeses like Parmesan, raw milk’s natural bacteria contribute to flavor development during aging. Soft cheeses like Brie or mozzarella, however, often benefit from pasteurized milk to ensure safety without compromising texture. Homogenized milk is generally less preferred for cheese making due to its altered fat structure, which can hinder proper curd formation. If using homogenized milk, opt for low-moisture cheeses like paneer, where texture is less critical.

Practical tips can streamline your selection process. For beginners, start with pasteurized, non-homogenized milk from a local dairy to balance safety and quality. If using raw milk, ensure it’s from a trusted source and handle it at temperatures below 40°F (4°C) to minimize bacterial growth. Always check local regulations, as raw milk sales are restricted in some regions. For homogenized milk, add 1–2 tablespoons of cream per gallon to improve fat distribution and curd yield.

The choice between raw, pasteurized, and homogenized milk isn’t just technical—it’s philosophical. Raw milk advocates prize its authenticity and flavor, while pasteurized milk offers consistency and safety. Homogenized milk, though less ideal, can still yield decent results with adjustments. Experimentation is key; try making the same cheese with different milks to observe how each affects flavor, texture, and aging potential. This hands-on approach will deepen your understanding of milk’s role in cheese making.

Ultimately, milk selection is a balance of science, tradition, and personal preference. Raw milk demands precision but rewards with complexity, pasteurized milk provides reliability, and homogenized milk requires creativity. Tailor your choice to the cheese’s requirements and your comfort level. With practice, you’ll develop an intuition for how milk transforms into cheese, turning this fundamental decision into an art form.

Big Cheese Revolver Mouse Trap: Mechanism, Efficiency, and User Guide

You may want to see also

Coagulants: Rennet, vinegar, or lemon juice are needed to curdle milk and start the cheese-making process

Curdling milk is the cornerstone of cheese making, and coagulants are the catalysts that transform liquid into solid. Rennet, vinegar, and lemon juice each bring distinct qualities to this process, influencing texture, flavor, and yield. Rennet, derived from animal sources or microbial cultures, contains chymosin, an enzyme that efficiently coagulates milk by breaking down k-casein proteins. This results in a clean break between curds and whey, ideal for hard cheeses like cheddar or gouda. For vegetarians or those seeking alternatives, vinegar and lemon juice offer acidity-driven coagulation. While less precise than rennet, they are perfect for soft, fresh cheeses like ricotta or paneer. Understanding these coagulants allows you to tailor your cheese-making to your desired outcome.

Choosing the right coagulant depends on the type of cheese you’re making and your dietary preferences. Rennet, whether animal-based or microbial, is the traditional choice for aged cheeses due to its ability to produce a firm, sliceable curd. Use approximately 1/4 teaspoon of liquid rennet diluted in cool, non-chlorinated water per gallon of milk, adding it slowly while stirring gently. For acid-coagulated cheeses, vinegar or lemon juice works by lowering the milk’s pH, causing it to curdle. Add 2–4 tablespoons of white vinegar or fresh lemon juice per gallon of milk, heating the milk to 180°F (82°C) first for best results. These methods are simpler and faster but yield softer, crumblier textures. Experimenting with these coagulants will help you master the art of cheese making.

While rennet provides consistency and control, acid coagulants like vinegar and lemon juice are more forgiving for beginners. However, their simplicity comes with limitations. Acid-coagulated cheeses have a shorter shelf life and lack the complexity of rennet-based varieties. For instance, ricotta made with vinegar is ready in under 30 minutes but lacks the depth of a traditional, aged cheese. Conversely, rennet-based cheeses require patience—aging can take weeks or months—but the payoff is a richer flavor and firmer texture. Consider your time, equipment, and desired outcome when selecting a coagulant.

Practical tips can elevate your cheese-making experience regardless of the coagulant you choose. Always use fresh, high-quality milk for the best results, and avoid ultra-pasteurized varieties, as they may not curdle properly. When using rennet, ensure your milk is at the correct temperature (typically 86–100°F or 30–38°C) for optimal enzyme activity. For acid coagulants, monitor the milk closely as it heats to prevent scorching. After adding the coagulant, let the mixture rest undisturbed for 5–10 minutes to allow curds to form. Finally, invest in a good thermometer and cheesecloth—these tools are essential for precision and straining. With the right coagulant and techniques, you’ll be crafting delicious cheeses in no time.

Perfect Pumpkin Cheesecake: Signs It's Ready to Serve

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Starter Cultures: Bacteria cultures help acidify milk and develop flavor in specific cheese varieties

Bacteria cultures, often referred to as starter cultures, are the unsung heroes of cheesemaking. These microscopic organisms play a pivotal role in transforming milk into cheese by acidifying it and developing the distinct flavors and textures we associate with different varieties. Without them, cheese would lack its characteristic tang, complexity, and structure. Starter cultures are not one-size-fits-all; they are carefully selected based on the type of cheese being made, with each culture contributing unique enzymatic activity and flavor profiles.

When choosing a starter culture, consider the cheese variety you’re aiming to create. For example, mesophilic cultures, which thrive at moderate temperatures (around 20–30°C), are ideal for cheeses like Cheddar, Gouda, and mozzarella. Thermophilic cultures, on the other hand, prefer higher temperatures (around 40–45°C) and are essential for hard cheeses like Parmesan and Swiss. Direct-set cultures, available in powdered form, are beginner-friendly and require no preparation, while bulk cultures, which need to be propagated in milk before use, offer greater control but demand more skill. Dosage is critical—typically, 1–2% of the milk volume is inoculated with culture, but always follow the manufacturer’s instructions for precision.

The science behind starter cultures is fascinating. As bacteria metabolize lactose (milk sugar), they produce lactic acid, lowering the milk’s pH and causing it to curdle. This process not only separates the curds from the whey but also creates the foundation for flavor development. For instance, *Lactococcus lactis* subsp. *cremoris* and *Lactococcus lactis* subsp. *lactis* are commonly used in Cheddar production, contributing nutty and buttery notes. In contrast, *Streptococcus thermophilus* and *Lactobacillus delbrueckii* subsp. *bulgaricus* are key players in Italian hard cheeses, imparting sharp, tangy flavors. Understanding these nuances allows cheesemakers to tailor their cultures to achieve desired outcomes.

Practical tips for working with starter cultures include maintaining strict hygiene to avoid contamination, as unwanted bacteria can ruin a batch. Always use sterile equipment and store cultures properly—most require refrigeration at 2–4°C. For bulk cultures, monitor the propagation process closely, ensuring the milk reaches the correct temperature and acidity before adding it to the main batch. If you’re new to cheesemaking, start with direct-set cultures and simpler cheeses like ricotta or paneer, which rely more on acidification from vinegar or lemon juice than bacterial cultures. As you gain confidence, experiment with more complex varieties that highlight the artistry of starter cultures.

In essence, starter cultures are the backbone of cheesemaking, bridging the gap between milk and cheese through their transformative abilities. By mastering their selection, dosage, and application, you can unlock the potential to craft cheeses with depth, character, and authenticity. Whether you’re a hobbyist or aspiring artisan, understanding these cultures is a cornerstone of the craft, turning a scientific process into a culinary masterpiece.

Carl's Jr. Chili Cheese Fries: Are They Still on the Menu?

You may want to see also

Sanitization: Clean and sterilize all equipment to prevent contamination and ensure safe cheese production

Sanitization is the cornerstone of safe cheese production, as even a single bacterium can spoil an entire batch. Contamination risks aren’t just theoretical—they’re inevitable without rigorous cleaning protocols. Pathogens like *Listeria* or *E. coli* thrive in dairy environments, and their presence can lead to foodborne illnesses or product recalls. Thus, treating sanitization as a non-negotiable step is essential, not optional.

Begin by disassembling all equipment—pots, molds, utensils, and thermometers—to ensure no crevices are overlooked. Wash everything in hot, soapy water, using a food-safe detergent, and scrub surfaces with a brush to remove milk residues. Rinse thoroughly to avoid soap traces, which can taint cheese flavor. After cleaning, sterilize tools by immersing them in a solution of 1 tablespoon of unscented bleach per gallon of water for 2 minutes, or boil them for 5 minutes. For non-heat-resistant items, use a commercial dairy sanitizer following the manufacturer’s dilution instructions.

While sanitizing, consider the material of your equipment. Stainless steel and food-grade plastic withstand high temperatures and chemicals, making them ideal for cheese making. Wooden tools, though traditional, require extra care—they must be thoroughly dried after sanitizing to prevent bacterial growth. Avoid porous materials like uncoated aluminum, which can react with dairy acids and compromise both safety and taste.

A common pitfall is rushing the drying process. Air-dry equipment on clean towels or racks to prevent recontamination from drying cloths. Store sanitized tools in a covered container or designated area to maintain cleanliness until use. Consistency is key—establish a sanitization routine before and after each batch, even if equipment appears clean. This discipline ensures that every step of cheese making, from curdling to aging, occurs in a contamination-free environment.

Finally, treat sanitization as an investment in your craft. While it adds time to the process, it safeguards the quality and safety of your cheese. Think of it as the invisible ingredient that distinguishes a successful batch from a failed one. By mastering this step, you’ll not only protect your product but also build trust with those who enjoy your creations.

Crunchy Cheese Perfection: Baking Shredded Cheese for Crispy Toppings

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The primary ingredients for cheese making are milk (cow, goat, sheep, or buffalo), rennet (or a vegetarian alternative) to coagulate the milk, and a starter culture to acidify it. Salt is also commonly used for flavor and preservation.

Essential equipment includes a large pot for heating milk, a thermometer to monitor temperature, a long-handled spoon for stirring, cheesecloth or butter muslin for draining, and containers or molds for shaping the cheese. Optional tools include a pH meter and a cheese press.

While you can use store-bought milk, raw or unpasteurized milk often yields better results due to its natural bacteria. If using pasteurized milk, ensure it’s not ultra-pasteurized (UP), as it may not curdle properly.

Temperature control is critical in cheese making, as it affects how the milk curdles and the final texture of the cheese. Most recipes require precise temperatures for heating milk, adding cultures, and draining curds, so a reliable thermometer is essential.