The question of what to call cheese that isn’t trademarked delves into the fascinating intersection of food nomenclature, intellectual property, and culinary tradition. While many cheeses, like Cheddar or Parmesan, are generic terms not protected by trademarks, others, such as Brie de Meaux or Stilton, are legally safeguarded due to their geographic origins or specific production methods. Understanding the distinction between trademarked and non-trademarked cheeses highlights how language, culture, and commerce shape the way we categorize and consume this beloved dairy product. It also raises broader questions about the balance between protecting artisanal traditions and fostering innovation in the global cheese market.

Explore related products

$1.18 $1.48

$0.97 $1.72

$0.97 $1.72

What You'll Learn

Generic Cheese Names

Cheese names that aren’t trademarked fall under the category of generic cheese names, often derived from their place of origin, production method, or key ingredients. Examples include Cheddar, Parmesan, and Feta, which have become universal descriptors rather than protected brands. These names are part of the public domain, allowing producers worldwide to use them without legal restriction, provided the product meets basic standards of identity. For instance, Cheddar refers to a hard, sharp cheese originally from England, but now produced globally, while Feta denotes a brined curd cheese traditionally made from sheep’s milk, though cow’s milk versions are common outside Greece. Understanding these names helps consumers identify cheese types based on expected flavor, texture, and use, regardless of the brand or region of production.

When crafting or selecting generic cheese names, clarity and tradition are paramount. Producers often lean on historical or regional descriptors to signal authenticity without infringing on trademarks. For example, Gouda (a Dutch cheese) and Brie (a French soft cheese) rely on their geographic roots to convey their style. However, caution is necessary: while these names are generic, specific terms like Asiago or Gruyère may have protected status in certain regions (e.g., the EU), requiring producers outside those areas to use qualifiers like "style" or "type." This balance between tradition and legality ensures consumers recognize the cheese while respecting intellectual property laws.

From a practical standpoint, generic cheese names simplify purchasing decisions. For instance, if a recipe calls for Mozzarella, any non-trademarked version will suffice, whether made from buffalo or cow’s milk. Similarly, Cottage Cheese universally refers to a fresh, lumpy cheese, though fat content (e.g., 1%, 2%, or full-fat) may vary. To maximize value, compare prices per weight and check ingredient lists for additives. For aging cheeses like Parmesan, look for terms like "aged 12 months" for deeper flavor, though this may increase cost. Pairing generic cheeses with specific uses—Cheddar for melting, Ricotta for baking—ensures optimal results without overpaying for branding.

The evolution of generic cheese names reflects broader trends in food globalization. As cheeses like Halloumi (a Cypriot grilling cheese) gain international popularity, their names become genericized, losing exclusivity to a single producer or region. This democratization benefits both consumers, who access diverse options, and producers, who tap into established markets. However, it also risks diluting cultural heritage, as mass production may prioritize cost over tradition. To preserve authenticity, consumers can seek certifications like "Traditional Speciality Guaranteed" (TSG) or opt for locally made versions. Ultimately, generic cheese names serve as a bridge between heritage and accessibility, guiding choices in an ever-expanding cheese landscape.

Bacterial Magic: Transforming Milk into Cheese Through Fermentation

You may want to see also

Public Domain Cheese Terms

Cheese names not protected by trademarks or geographical indications (GIs) fall into the public domain, allowing anyone to use them freely. Terms like "Cheddar," "Gouda," and "Swiss" are prime examples, as their origins have long been generalized beyond specific producers or regions. This openness fosters innovation, enabling cheesemakers to experiment with styles while leveraging familiar names to attract consumers. However, it also risks diluting quality standards, as anyone can produce and label a cheese as "Cheddar" regardless of adherence to traditional methods.

Analyzing the impact of public domain cheese terms reveals both opportunities and challenges. On one hand, these terms democratize cheese production, lowering barriers for small-scale artisans and startups. For instance, a new cheesemaker in Wisconsin can label their product "Colby" without legal repercussions, capitalizing on the name’s recognition. On the other hand, the lack of regulation can lead to consumer confusion, as the term "Colby" may describe vastly different products in terms of texture, flavor, or aging. This underscores the need for voluntary quality standards or certifications to maintain trust.

To navigate public domain cheese terms effectively, consider these practical steps. First, research the historical and cultural context of the term to understand its traditional characteristics. For example, "Brie" typically refers to a soft, bloomy-rind cheese, though public domain status allows for variations. Second, clearly communicate your product’s unique attributes on packaging or marketing materials to differentiate it. Third, explore niche markets or specialty audiences that value innovation over strict tradition. For instance, a "Gouda" infused with local herbs might appeal to adventurous consumers seeking novel flavors.

A comparative analysis highlights the contrast between public domain terms and protected ones like "Parmigiano-Reggiano" or "Roquefort." While protected names guarantee specific production methods and origins, public domain terms offer flexibility but lack assurance. This duality suggests a middle ground: adopting public domain terms while voluntarily adhering to traditional practices. For example, labeling a cheese as "Chèvre" while using goat’s milk and French techniques can honor tradition without legal constraints. Such an approach balances creativity with respect for heritage.

Finally, the descriptive richness of public domain cheese terms lies in their versatility. Terms like "Blue Cheese" or "Mozzarella" evoke sensory imagery—crumbly veins or stretchy texture—without dictating precise recipes. This allows cheesemakers to reinterpret classics, such as crafting a smoked Mozzarella or a vegan Blue Cheese alternative. By embracing this flexibility, producers can cater to diverse dietary preferences and culinary trends while keeping the essence of the term intact. Ultimately, public domain cheese terms are not just labels but invitations to reimagine tradition.

Banned Cheese: Uncovering the Illegal Varieties in the United States

You may want to see also

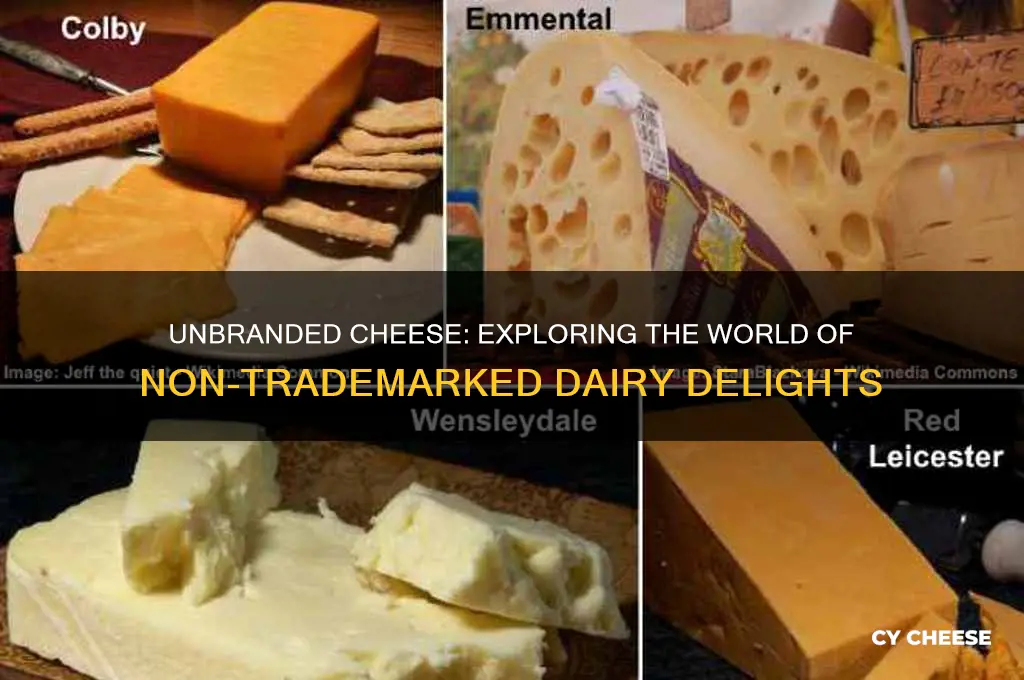

Unbranded Cheese Varieties

Cheese that isn't trademarked often falls into the category of generic or traditional varieties, crafted and enjoyed for centuries without proprietary claims. These unbranded cheeses are typically named after their region of origin, production method, or key ingredients, making them accessible to producers worldwide. Examples include Cheddar, Gouda, and Feta, which, despite their widespread recognition, lack exclusive ownership. This openness allows artisans and large-scale manufacturers alike to create their versions, fostering diversity in flavor, texture, and quality.

Analyzing the appeal of unbranded cheese varieties reveals their role in culinary heritage and innovation. Unlike trademarked cheeses, which may restrict production techniques or recipes, generic cheeses offer a blank canvas for experimentation. For instance, while Parmesan is a protected designation of origin (PDO) in Italy, "hard grating cheese" remains an unbranded alternative, enabling producers in other countries to develop similar products. This flexibility encourages local adaptations, such as using regional milk sources or aging processes, resulting in unique profiles that reflect their terroir.

For home cooks and cheese enthusiasts, understanding unbranded varieties simplifies ingredient substitutions and recipe customization. If a recipe calls for "Swiss cheese," you’re not limited to a specific brand but can choose from Emmental, Jarlsberg, or any semi-hard cheese with eye formation. Similarly, "fresh cheese" encompasses ricotta, cottage cheese, and queso fresco, allowing for creative swaps based on availability or dietary preferences. This versatility reduces reliance on branded products and promotes exploration of lesser-known options.

When selecting unbranded cheeses, consider the following practical tips: first, focus on the cheese’s characteristics (e.g., melting ability, saltiness, or crumbly texture) rather than its name. Second, inquire about the production process, as artisanal methods often yield richer flavors. Third, pair unbranded cheeses with complementary ingredients to enhance their natural qualities—for example, serving aged Gouda with caramelized nuts or spreading fresh chèvre on crusty bread. By prioritizing these factors, you can elevate dishes without being constrained by trademarks.

In conclusion, unbranded cheese varieties embody the essence of shared culinary traditions, offering freedom and creativity in both production and consumption. Their lack of trademark protection ensures accessibility and encourages innovation, making them indispensable in kitchens worldwide. Whether you’re a chef, home cook, or cheese aficionado, embracing these generic cheeses unlocks a world of possibilities, proving that sometimes, the absence of a brand name is the ultimate mark of authenticity.

Understanding Cheese Measurements: How Many Slices in 3/4 Pound?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$0.97 $1.72

Common Cheese Labels

Cheese that isn't trademarked often falls under generic or common labels, which describe the type, style, or production method rather than a brand name. These labels are essential for consumers to understand what they're buying, as they provide clear, standardized descriptions. For instance, terms like "Cheddar," "Mozzarella," or "Goat Cheese" are widely recognized and not owned by any single producer. These names are rooted in tradition, geography, or the cheese-making process, allowing them to remain in the public domain.

Analyzing common cheese labels reveals a pattern: they often describe the milk source (cow, goat, sheep), texture (hard, soft, semi-soft), or aging process (fresh, aged, vintage). For example, "Parmesan" refers to a hard, aged cheese made from cow’s milk, while "Feta" denotes a brined, crumbly cheese typically made from sheep’s or goat’s milk. These labels are not trademarked because they describe categories rather than specific products. However, it’s crucial to note that while the names are generic, the quality and production methods can vary widely between producers.

When shopping for non-trademarked cheeses, understanding these labels can help you make informed choices. For instance, "Brie" always refers to a soft, bloomy-rind cheese, but the flavor and texture can differ based on the region and producer. Similarly, "Gouda" is a semi-hard cheese that can range from young and mild to aged and nutty. To ensure you’re getting what you expect, look for additional descriptors like "aged 12 months" or "raw milk," which provide more detail about the product.

A practical tip for navigating common cheese labels is to familiarize yourself with regional variations. For example, "Cheddar" originated in England but is now produced globally, with differences in taste and texture depending on the location. Similarly, "Gruyère" is a Swiss cheese with strict production standards, but similar cheeses are made elsewhere under different names. By understanding these nuances, you can better appreciate the diversity within each category and choose cheeses that align with your preferences.

In conclusion, common cheese labels serve as a universal language for describing non-trademarked cheeses. They provide clarity and consistency, allowing consumers to identify types based on traditional characteristics. While these labels are not proprietary, they are deeply rooted in cheese-making history and culture. By mastering these terms and their implications, you can confidently explore the vast world of cheese, knowing exactly what to expect from each bite.

Cheese Sticks as Meat Alternatives: Nutritional Value and Dietary Role

You may want to see also

Non-Trademarked Cheese Types

Cheese names often reflect their origin, production method, or key ingredients, but not all are protected by trademarks. Non-trademarked cheese types are those that lack legal exclusivity, allowing producers worldwide to use the same name without restriction. Examples include Cheddar, Gouda, and Feta, which have become generic terms due to widespread adoption. This lack of trademark protection can lead to variations in quality and authenticity, as anyone can produce and label these cheeses without adhering to traditional standards.

Analyzing the impact of non-trademarked cheese names reveals both advantages and drawbacks. On one hand, the absence of trademark restrictions fosters innovation, as producers can experiment with recipes while using familiar names. For instance, a cheesemaker in the U.S. might create a smoked Cheddar, adding a unique twist to the classic. On the other hand, this freedom can dilute the cultural and historical significance of these cheeses. A consumer might encounter a "Gouda" that bears little resemblance to the traditional Dutch version, leading to confusion and mistrust.

For those looking to produce or purchase non-trademarked cheeses, understanding the nuances is key. Start by researching the traditional methods and ingredients associated with the cheese type. For example, authentic Feta is made from sheep’s or goat’s milk in Greece, but non-trademarked versions may use cow’s milk or be produced elsewhere. When producing such cheeses, clearly label any deviations from the traditional recipe to maintain transparency. Consumers should look for certifications like PDO (Protected Designation of Origin) or seek out artisanal producers who prioritize authenticity.

Comparing non-trademarked cheeses to their trademarked counterparts highlights the importance of context. Trademarked cheeses, such as Brie de Meaux, are protected by strict regulations ensuring consistency and quality. Non-trademarked cheeses, however, offer flexibility but require vigilance. For instance, while both trademarked and non-trademarked Mozzarella exist, the latter may vary significantly in texture and flavor. This comparison underscores the need for consumers to educate themselves and for producers to uphold ethical standards, even in the absence of legal constraints.

In practical terms, incorporating non-trademarked cheeses into cooking or cheeseboards can be both rewarding and challenging. Pair a non-trademarked Cheddar with a sharp, tangy chutney to complement its robust flavor, or use a non-trademarked Gruyère in a classic fondue recipe. However, always taste-test beforehand, as quality can vary widely. For aging non-trademarked cheeses at home, maintain a consistent temperature of 50-55°F (10-13°C) and humidity of 80-85% to encourage proper mold development. With careful selection and preparation, these cheeses can be just as delightful as their trademarked counterparts.

Mastering Homemade Cheese Fondue: Easy Tips for Your Fondue Pot

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Cheese that isn't trademarked is simply referred to by its generic name, such as cheddar, mozzarella, or gouda, without any specific brand or proprietary designation.

No, generic cheese names like "cheddar" or "brie" cannot be trademarked because they describe the type of cheese rather than a specific brand or product.

While generic cheese names cannot be trademarked, brands can use them descriptively as part of their product names, as long as they don’t imply exclusivity or ownership of the term.

Trademarked cheeses often include a brand name, logo, or symbol (™ or ®) on their packaging. Generic cheeses are labeled only by their type (e.g., "Swiss cheese") without such branding indicators.