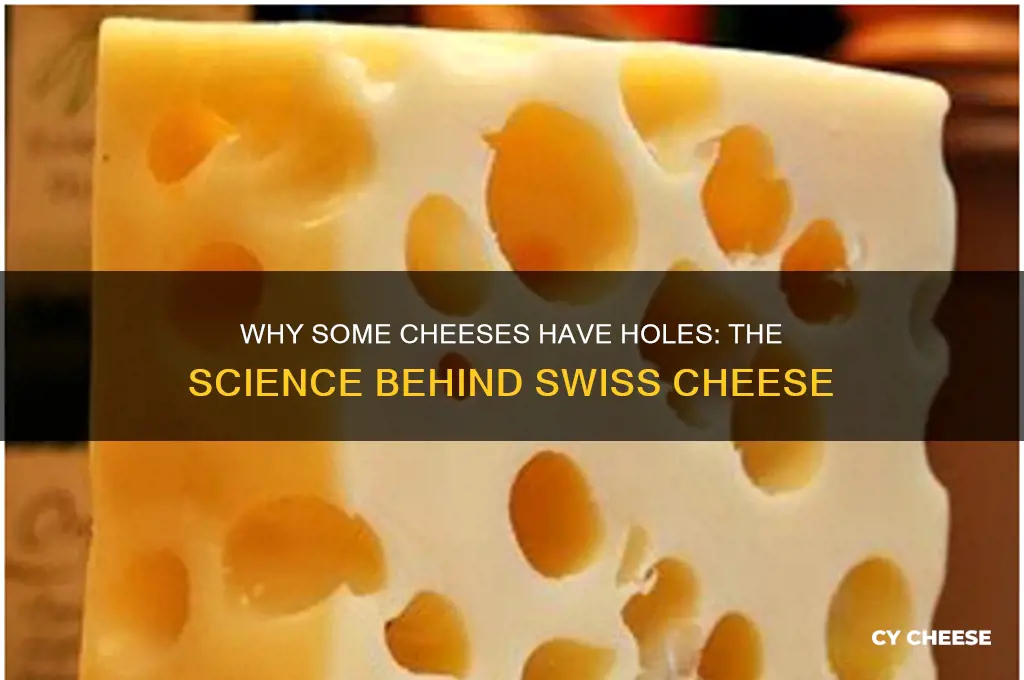

Some cheeses, like Swiss cheese, are famous for their distinctive holes, which are actually air pockets formed during the aging process. These holes, technically called eyes, are the result of carbon dioxide gas produced by bacteria as they ferment the cheese. Specifically, in Swiss cheese varieties such as Emmental, the bacteria *Propionibacterium freudenreichii* metabolizes lactic acid, releasing gas that gets trapped in the curd, creating the characteristic holes. This process not only contributes to the cheese's unique appearance but also influences its texture and flavor, making it a fascinating example of how microbiology shapes culinary traditions.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Gas Formation During Fermentation

The distinctive holes in cheeses like Emmental and Gruyère are not mere quirks of nature but the result of a precise biological process: gas formation during fermentation. This phenomenon occurs when specific bacteria, notably *Propionibacterium freudenreichii*, metabolize lactic acid in the curd, producing carbon dioxide (CO₂) as a byproduct. As the cheese ages, this gas becomes trapped within the semi-solid matrix, forming the characteristic bubbles that expand into holes. The size and distribution of these holes depend on factors such as curd density, humidity, and aging temperature, making hole formation both a science and an art.

To encourage optimal gas formation, cheesemakers must control fermentation conditions meticulously. The curd should be cut into larger pieces to allow gas pockets to develop, and the cheese should be aged in a high-humidity environment (around 90%) at temperatures between 18–22°C (64–72°F). *Propionibacterium* requires a low-oxygen atmosphere to thrive, so the cheese is often wrapped in wax or stored in sealed containers during aging. Additionally, the curd’s pH should be maintained between 5.3 and 5.5 to support bacterial activity without compromising texture. Deviations from these parameters can result in uneven hole distribution or a lack of holes altogether.

A comparative analysis reveals that not all cheeses develop holes, as the process relies on the presence of specific bacteria and fermentation conditions. For instance, Cheddar and Brie lack holes because they are fermented primarily by lactic acid bacteria, which do not produce CO₂ in significant quantities. In contrast, Emmental’s hole formation is a deliberate outcome of introducing *Propionibacterium* during the cheesemaking process. This distinction highlights the role of microbial selection in determining cheese characteristics, underscoring the importance of understanding fermentation dynamics in cheesemaking.

For home cheesemakers attempting holey cheeses, practical tips can enhance success. Start by using a mesophilic starter culture that includes *Propionibacterium*, available from specialty suppliers. Ensure the curd is handled gently during pressing to preserve its openness, and age the cheese for a minimum of 2–3 months to allow gas pockets to develop fully. Regularly monitor the aging environment, using a hygrometer to maintain humidity and a thermometer to track temperature. While the process demands patience and precision, the reward is a cheese with the unmistakable texture and appearance of traditional Swiss varieties.

Muenster Cheese Slices: How Many Fit in 8 Ounces?

You may want to see also

Role of Starter Cultures

The distinctive holes in cheeses like Emmental and Gruyère, often whimsily called "eyes," are not random quirks but the result of a precise biological process. At the heart of this phenomenon lies the role of starter cultures—specific strains of bacteria intentionally added to milk during cheesemaking. These microorganisms, typically lactic acid bacteria such as *Lactococcus lactis* and *Streptococcus thermophilus*, kickstart fermentation by converting lactose (milk sugar) into lactic acid. This acidification lowers the milk’s pH, causing it to curdle and form the basis of cheese. However, their contribution to hole formation goes beyond curdling.

During the aging process, starter cultures continue to metabolize, producing carbon dioxide (CO₂) as a byproduct. In cheeses like Emmental, the curd is cut and heated in a way that traps this CO₂ within the cheese matrix. As the cheese ages, the gas accumulates in pockets, eventually forming the characteristic holes. The size and distribution of these holes depend on factors like the specific bacterial strains used, their dosage (typically 1–2% of milk volume), and the environmental conditions during aging. For instance, a higher concentration of *Propionibacterium freudenreichii*, a secondary bacteria often added to Swiss-type cheeses, enhances CO₂ production, leading to larger holes.

To achieve optimal hole formation, cheesemakers must carefully control the starter culture’s activity. Over-acidification, caused by excessive bacterial growth, can lead to uneven or small holes, while insufficient fermentation results in a dense, holeless texture. Practical tips include maintaining a consistent temperature (around 20–24°C) during aging and monitoring humidity levels to ensure the bacteria thrive. For home cheesemakers, using pre-measured starter culture packets and following precise timing guidelines can replicate this process effectively.

Comparatively, cheeses without holes, like Cheddar or Brie, use different starter cultures or aging techniques that minimize CO₂ retention. This highlights the specificity of starter cultures in dictating cheese texture. In contrast, Swiss-type cheeses rely on a symbiotic relationship between primary lactic acid bacteria and secondary propionic acid bacteria, which further break down lactic acid into CO₂ and propionic acid, contributing to flavor and hole development. This dual-culture system underscores the complexity and precision required in crafting holey cheeses.

In conclusion, starter cultures are not just catalysts for fermentation but architects of cheese structure. Their selection, dosage, and management determine whether a cheese will develop holes or remain compact. For cheesemakers, understanding this role is essential for mastering the art of holey cheeses, blending science with tradition to create a product that’s as fascinating as it is delicious.

Cheese and Digestion: Constipation or Diarrhea? Unraveling the Truth

You may want to see also

Effect of Aging Process

The holes in certain cheeses, like Swiss or Emmental, are a direct result of the aging process, specifically the activity of carbon dioxide-producing bacteria. During aging, these bacteria metabolize lactic acid, releasing gas that becomes trapped within the curd, forming the characteristic holes. This process is not just a visual quirk but a critical aspect of developing the cheese's texture and flavor profile.

Analytical Insight: The size and distribution of holes in cheese can indicate the conditions under which it was aged. For instance, larger holes often suggest a warmer aging environment, as higher temperatures accelerate bacterial activity. Conversely, smaller, more uniform holes typically result from cooler, more controlled conditions. This relationship between temperature and hole formation highlights the precision required in cheese aging to achieve desired characteristics.

Instructive Guidance: To encourage hole formation in homemade cheese, maintain a consistent aging temperature between 68°F and 75°F (20°C and 24°C). Use a starter culture containing *Propionibacterium freudenreichii*, the bacterium responsible for gas production. Ensure the cheese is aged for at least 4 to 6 weeks, as this allows sufficient time for the bacteria to produce enough carbon dioxide to form visible holes. Regularly flip the cheese to promote even gas distribution.

Comparative Perspective: Unlike cheeses aged for shorter periods, those aged longer tend to develop more pronounced holes and a nuttier flavor. For example, a young Swiss cheese aged 2 months may have small, sparse holes, while a 6-month-aged version will exhibit larger, more numerous holes and a deeper, more complex taste. This comparison underscores how the aging process not only affects hole formation but also enhances the overall sensory experience of the cheese.

Practical Tip: If you’re aging cheese at home, monitor humidity levels to prevent the rind from drying out, which can inhibit bacterial activity. Aim for a relative humidity of 85–90% in your aging environment. Use a hygrometer to measure humidity and a humidifier or water tray to adjust as needed. This ensures the bacteria remain active throughout the aging process, maximizing hole formation and flavor development.

Takeaway: The aging process is a delicate balance of time, temperature, and microbial activity that directly influences the presence and characteristics of holes in cheese. By understanding and controlling these factors, both artisanal cheesemakers and home enthusiasts can craft cheeses with the desired texture and flavor, turning a simple curd into a masterpiece of fermentation science.

Grating Cheese: Measure Before or After for Perfect Recipes?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Types of Cheese with Holes

The presence of holes in cheese, often referred to as "eyes," is a distinctive feature that sparks curiosity. These holes are primarily the result of carbon dioxide gas released by bacteria during the fermentation process. While not all cheeses develop holes, those that do belong to a specific category known as Swiss-type or Alpine cheeses. Understanding the science and artistry behind these cheeses reveals why they stand out in the dairy world.

One of the most iconic holey cheeses is Emmental, originating from Switzerland. Its large, walnut-sized holes are a hallmark of proper fermentation. The bacteria *Streptococcus thermophilus* and *Propionibacterium freudenreichii* work together to produce lactic acid and carbon dioxide, respectively. The gas becomes trapped in the curd, forming bubbles that solidify into holes. Emmental’s mild, nutty flavor and firm texture make it a versatile choice for sandwiches, fondue, or melting over dishes. For optimal enjoyment, serve it at room temperature to enhance its creamy mouthfeel.

Another notable example is Appenzeller, a Swiss cheese with smaller, irregular holes compared to Emmental. Aged for a minimum of three months, it boasts a tangy, fruity flavor profile due to its brine wash during maturation. The holes in Appenzeller are less prominent but still contribute to its unique texture. Pair it with robust wines or use it in hearty dishes like cheese soups or gratins. Its complexity makes it a favorite among cheese connoisseurs seeking depth and character.

For those exploring beyond Switzerland, Leerdammer offers a Dutch twist on holey cheese. Developed in the 1970s, it combines the hole structure of Emmental with a smoother, creamier texture. Leerdammer’s mild, buttery flavor appeals to a broader audience, especially children or those new to semi-hard cheeses. Its meltability also makes it an excellent choice for grilled cheese sandwiches or burgers. Store it in wax paper and consume within two weeks of opening to preserve its freshness.

Lastly, Tête de Moine, a Swiss cheese with a unique production method, deserves mention. While its holes are finer and less pronounced, its standout feature is its traditional shaving technique. Using a *girolle*, the cheese is scraped into thin, delicate rosettes that melt on the tongue. This presentation enhances its nutty, slightly spicy flavor. Ideal for cheese boards or as a garnish, Tête de Moine showcases how hole structure, though subtle, contributes to a cheese’s overall experience.

In summary, holey cheeses are a testament to the precision of cheesemaking. From the large eyes of Emmental to the subtle holes in Tête de Moine, each variety offers a distinct texture and flavor profile. Understanding their origins and characteristics allows enthusiasts to appreciate and utilize them effectively, whether in cooking or savoring them on their own.

What Does Al Forno Mean? Cheesy Ziti Baking Secrets Revealed

You may want to see also

Impact of Milk Treatment

The size and distribution of holes in cheese, often a hallmark of varieties like Emmental or Swiss, are directly influenced by the treatment of milk during the early stages of cheesemaking. One critical factor is the method of pasteurization. High-temperature, short-time (HTST) pasteurization, which heats milk to 72°C (161°F) for 15 seconds, can denature whey proteins more extensively than low-temperature, long-time (LTLT) pasteurization at 63°C (145°F) for 30 minutes. This denaturation affects the curd’s ability to retain carbon dioxide gas produced by starter cultures, leading to smaller or fewer holes. Artisanal cheesemakers often prefer raw milk or LTLT pasteurization to preserve the natural microbial flora and protein structure, fostering optimal gas retention and larger holes.

Another key aspect of milk treatment is the addition of starter cultures and their dosage. For hole formation, specific bacteria like *Propionibacterium freudenreichii* are essential, as they produce carbon dioxide during the slow fermentation of lactate. The concentration of these cultures matters: a dosage of 1–2% (based on milk volume) is typically used for Emmental, but higher doses can accelerate fermentation, causing uneven hole distribution. Timing is equally critical; allowing the cheese to age at 24–26°C (75–79°F) for 2–3 months ensures the bacteria have sufficient time to create the characteristic holes.

The choice of coagulation method also plays a role. Traditional rennet coagulation, which forms a stronger curd, is ideal for hole development as it traps gas more effectively. However, using microbial transglutaminase or acid coagulation can weaken the curd structure, resulting in smaller or collapsed holes. For home cheesemakers, using 0.02–0.05% rennet (by milk weight) and cutting the curd into 1.5 cm cubes ensures a balance between firmness and gas retention.

Finally, the impact of milk treatment extends to the milk’s fat content and homogenization. Whole milk, with its higher fat globules, provides a better matrix for gas retention compared to skimmed or homogenized milk. Homogenization, which breaks down fat globules, disrupts this structure, often leading to fewer holes. For optimal results, use non-homogenized whole milk with a fat content of 3.5–4%, and avoid ultra-high-temperature (UHT) treated milk, as it severely alters protein functionality.

In summary, the treatment of milk—from pasteurization method to starter culture dosage, coagulation technique, and fat content—dictates the size, number, and distribution of holes in cheese. Precision in these steps is not just a technical detail but an art that distinguishes a perfectly holed Emmental from a lesser imitation. For cheesemakers, understanding these variables is key to mastering the craft.

Uncovering Atoned Horror Cheese Spots: Are Any Left to Explore?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The holes in cheese, like Swiss or Emmental, are caused by carbon dioxide gas released by bacteria during the aging process. These bacteria, such as *Propionibacterium freudenreichii*, produce the gas as they break down lactic acid in the cheese.

The holes in cheese are naturally occurring. They form as a result of bacterial activity during the cheese-making and aging process, not from any artificial additives or processes.

No, only specific types of cheese, such as Swiss, Emmental, and some varieties of Gruyère, have holes. These holes are characteristic of cheeses made with specific bacteria and aging techniques.

The size and number of holes can be an indicator of how the cheese was made and aged, but they don’t necessarily determine quality. Consistent, evenly distributed holes are often a sign of proper fermentation, but taste and texture are more important quality factors.

Yes, it’s possible to make cheese with holes at home, but it requires specific bacteria cultures (like *Propionibacterium*) and careful control of temperature and humidity during aging. It’s a more advanced cheese-making process compared to simpler varieties.