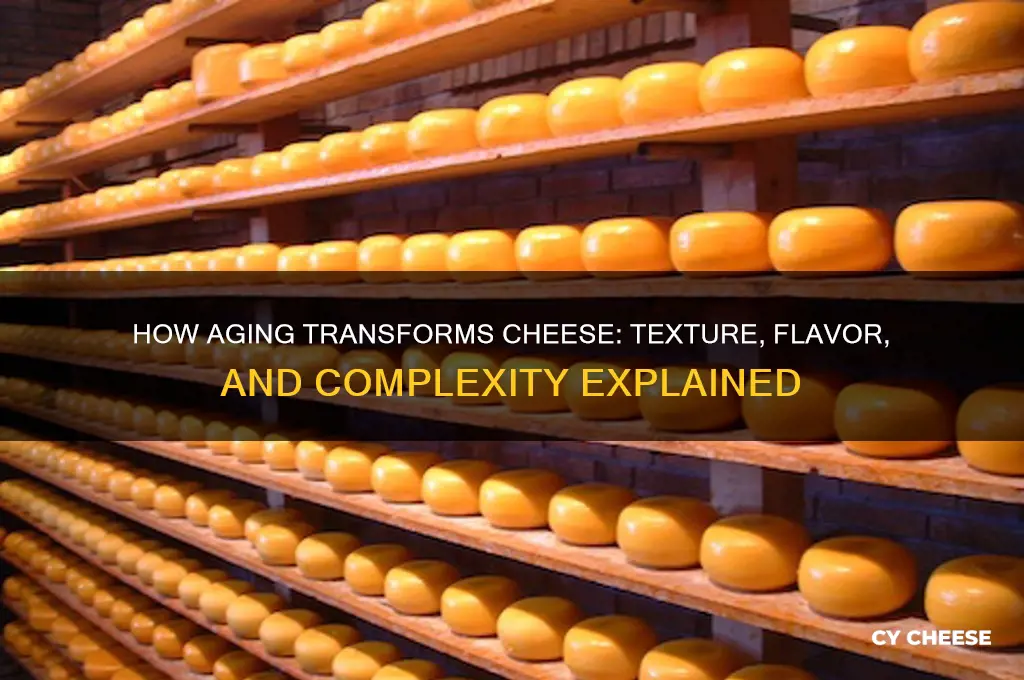

The aging process, also known as ripening, is a crucial step in cheese production that significantly transforms its texture, flavor, and aroma. During this stage, cheese is stored under controlled conditions of temperature and humidity, allowing enzymes, bacteria, and molds to break down proteins and fats, resulting in complex chemical reactions. As cheese ages, its moisture content decreases, leading to a firmer texture, while the breakdown of proteins and fats produces a wide range of flavor compounds, from mild and creamy to sharp and pungent. The aging process also encourages the development of eyes (holes) in some cheeses, such as Swiss, and the formation of a rind, which can range from soft and bloomy to hard and crusty. Ultimately, the duration and method of aging determine the unique characteristics of each cheese variety, making it a fascinating and essential aspect of the cheese-making art.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Texture Changes: Cheese hardens or crumbles as moisture evaporates during aging

- Flavor Development: Enzymes break down proteins, creating complex, deeper flavors over time

- Color Transformation: Rind and interior darken due to oxidation and microbial activity

- Aroma Evolution: Volatile compounds increase, producing stronger, more distinct smells

- Moisture Loss: Aging reduces water content, concentrating flavors and altering consistency

Texture Changes: Cheese hardens or crumbles as moisture evaporates during aging

As cheese ages, its texture undergoes a dramatic transformation, primarily due to moisture loss. This process, known as syneresis, causes the cheese to harden or crumble, depending on its initial moisture content and aging conditions. For example, a young, moist cheese like fresh mozzarella contains around 55-60% water, while a well-aged Parmigiano-Reggiano can drop to 30-32% moisture. This significant reduction in water content is a key driver of texture change.

The science behind this phenomenon lies in the breakdown of the cheese matrix. As moisture evaporates, the protein and fat molecules within the cheese draw closer together, forming a denser, more compact structure. In harder cheeses, this results in a firm, often granular texture, ideal for grating or shaving. Think of the crystalline, crumbly texture of aged Gouda or the flaky, brittle nature of long-aged Cheddar. Softer cheeses, on the other hand, may develop a drier, more friable rind while retaining a slightly moist interior, as seen in aged goat cheeses.

To control this process, cheesemakers manipulate aging conditions such as temperature (typically 10-15°C), humidity (85-95%), and air circulation. For instance, a higher humidity level slows moisture loss, resulting in a softer texture, while lower humidity accelerates drying and hardening. Home enthusiasts can experiment with aging cheese in a wine fridge or a dedicated cheese cave, monitoring humidity with a hygrometer and adjusting as needed. Aim for a consistent environment to achieve predictable texture changes.

Practical tips for home aging include wrapping cheese in cheese paper or breathable waxed cloth to allow moisture to escape gradually. Avoid plastic wrap, which traps moisture and can lead to mold or off-flavors. Regularly inspect the cheese, flipping it weekly to ensure even drying. For harder cheeses, aim for an aging period of 6-12 months, while softer varieties may only require 2-4 weeks. Remember, the goal is to strike a balance between moisture loss and flavor development, as over-drying can make cheese unpalatably hard or chalky.

In conclusion, understanding how moisture loss affects cheese texture during aging empowers both cheesemakers and enthusiasts to craft desired outcomes. By controlling environmental factors and monitoring progress, one can transform a simple curd into a complex, textured masterpiece. Whether aiming for a crumbly blue cheese or a shatteringly hard Pecorino, the key lies in mastering the delicate dance of moisture evaporation and its impact on the cheese matrix.

Whataburger's Double Bacon Cheese Burger: Toppings and Dressing Explained

You may want to see also

Flavor Development: Enzymes break down proteins, creating complex, deeper flavors over time

Enzymes are the unsung heroes of cheese aging, acting as microscopic chefs that transform simple proteins into a symphony of flavors. These biological catalysts, present in milk and often added during cheesemaking, work tirelessly as the cheese matures. Their primary task? Breaking down large, complex proteins into smaller peptides and amino acids. This process is not just a chemical reaction; it’s the foundation of flavor development. For instance, in a young cheddar, the proteins remain largely intact, resulting in a mild, milky taste. But after 6 to 12 months of aging, enzymes like plasmin and rennet-derived proteases begin to dismantle these proteins, releasing compounds that contribute to nutty, buttery, or even sharp notes. The longer the cheese ages, the more pronounced and layered these flavors become.

Consider the difference between a 6-month-old Gruyère and a 12-month-old version. The younger cheese retains a sweeter, more delicate profile, while its older counterpart boasts a deeper, more complex flavor with hints of caramel and toasted nuts. This transformation is directly tied to enzyme activity, which accelerates as moisture evaporates and the cheese’s structure changes. For home cheesemakers, understanding this process is key. To encourage flavor development, maintain a consistent aging temperature (ideally 50–55°F) and humidity (85–90%). These conditions optimize enzyme activity without promoting unwanted mold growth. Additionally, flipping the cheese regularly ensures even moisture distribution, allowing enzymes to work uniformly throughout the wheel.

Not all enzymes operate at the same pace or intensity. Some, like lipases, break down fats alongside proteins, adding pungent or piquant flavors often found in aged pecorino or blue cheeses. Others, such as glycosidases, target carbohydrates, contributing to sweetness or umami. The interplay of these enzymes depends on the cheese variety and aging conditions. For example, a semi-soft cheese like Brie relies on surface molds and enzymes to create its creamy texture and earthy flavor, while a hard cheese like Parmesan depends on prolonged enzyme activity to develop its granular texture and savory depth. Experimenting with aging times—starting at 3 months and extending to 24 months or more—allows you to observe how enzymes progressively shape flavor profiles.

Practical tip: If you’re aging cheese at home, monitor the rind’s appearance and aroma as indicators of enzyme activity. A rind that darkens or becomes more textured suggests active protein breakdown. Similarly, a deeper, more complex smell indicates that flavors are intensifying. For cheeses prone to excessive moisture loss, wrap them in cheese paper or breathable waxed cloth to retain enough humidity for enzymes to function. Avoid plastic wrap, which traps moisture and can lead to off-flavors or spoilage. By controlling these variables, you can harness the power of enzymes to craft cheeses with flavors that evolve from simple to sublime.

Counting Weight Watchers Points in a Whopper with Cheese

You may want to see also

Color Transformation: Rind and interior darken due to oxidation and microbial activity

As cheese ages, its appearance undergoes a striking metamorphosis, particularly in the darkening of both the rind and interior. This transformation is a direct result of oxidation and microbial activity, two key processes that contribute to the cheese's evolving character. The rind, often the first to exhibit these changes, develops a deeper, richer hue, ranging from golden brown to near black, depending on the cheese variety and aging conditions. Simultaneously, the interior may take on a more intense, sometimes ivory or yellowish tone, signaling the complex chemical reactions occurring within.

To understand this phenomenon, consider the role of oxidation. As cheese is exposed to air, oxygen reacts with the fats and proteins present, leading to the breakdown of these compounds. This process is akin to the browning of an apple when cut and left exposed. In cheese, oxidation not only darkens the color but also contributes to the development of nutty, caramelized, or even umami flavors. For instance, aged Gouda owes its distinctive dark exterior and rich, complex taste to prolonged oxidation during its maturation period, which can span from 1 to over 5 years.

Microbial activity plays an equally vital role in this color transformation. Bacteria and molds on the rind metabolize lactose and proteins, producing enzymes that further break down the cheese’s structure. Certain molds, such as *Penicillium camemberti* in Camembert or *Penicillium roqueforti* in blue cheeses, actively contribute to darkening by releasing pigments as they grow. These microorganisms thrive in specific humidity and temperature conditions—typically 85-95% humidity and 45-55°F (7-13°C)—which cheesemakers carefully control to encourage desired microbial development.

Practical tips for observing or managing this process include monitoring aging environments closely. Home cheesemakers should ensure proper airflow to facilitate oxidation while maintaining consistent temperature and humidity levels to support microbial activity. For those aging harder cheeses like Parmesan, flipping the cheese regularly can promote even darkening of the rind. Conversely, softer cheeses like Brie may require less handling to preserve their delicate microbial ecosystems.

In conclusion, the darkening of cheese during aging is a visually captivating indicator of the intricate interplay between oxidation and microbial activity. This transformation not only enhances the cheese’s aesthetic appeal but also deepens its flavor profile, making it a cornerstone of the aging process. By understanding and controlling these mechanisms, cheesemakers can craft products that embody the full spectrum of sensory experiences cheese has to offer.

Slicing Cheese: Uncovering the Ounce Count in Every Slice

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Aroma Evolution: Volatile compounds increase, producing stronger, more distinct smells

As cheese ages, its aroma undergoes a dramatic transformation, becoming more intense and complex. This evolution is driven by the increase in volatile compounds, which are the chemical molecules responsible for the smells we detect. These compounds are produced through the breakdown of proteins and fats by bacteria and enzymes during the aging process. For instance, a young cheddar might have a mild, milky scent, but after 12 to 18 months of aging, it develops sharp, tangy notes with hints of nuttiness and even a faint fruity undertone. This change is not just a matter of time; it’s a precise interplay of microbiology and chemistry.

To understand this process, consider the role of lipolysis and proteolysis. Lipolysis breaks down fats into free fatty acids, some of which are volatile and contribute to aromas like butteriness or creaminess. Proteolysis, on the other hand, degrades proteins into amino acids and peptides, leading to savory, brothy, or even meaty smells. In aged Parmigiano-Reggiano, for example, the concentration of volatile compounds like butyric acid and acetic acid increases significantly, creating its signature pungent and slightly acidic aroma. These reactions are temperature- and humidity-dependent, meaning a cheese aged at 50°F (10°C) and 85% humidity will develop differently than one aged at 55°F (13°C) and 90% humidity.

Practical tips for maximizing aroma evolution include monitoring the aging environment closely. For home cheesemakers, investing in a hygrometer and thermometer is essential. Aim for a consistent temperature range of 45°F to 55°F (7°C to 13°C) and adjust humidity levels by misting the cheese or using a humidifier. Regularly flip the cheese to ensure even exposure to air, which encourages the growth of surface molds that contribute to aroma complexity. For example, a blue cheese like Roquefort develops its distinctive earthy, spicy smell through the activity of Penicillium roqueforti, which thrives in cooler, moist conditions.

Comparatively, the aging of soft cheeses like Brie or Camembert showcases a different aroma profile. Here, the white mold rind (Penicillium camemberti) plays a central role in producing volatile compounds like methyl ketones, which give off a mushroomy, ammonia-like scent. These cheeses age more quickly, typically over 3 to 4 weeks, but their aroma development is just as profound. Unlike hard cheeses, soft cheeses require higher humidity (around 95%) and slightly warmer temperatures (50°F to 54°F or 10°C to 12°C) to achieve optimal flavor.

In conclusion, the aroma evolution in aged cheese is a fascinating interplay of science and art. By understanding the mechanisms behind volatile compound production and controlling aging conditions, cheesemakers can craft distinct sensory experiences. Whether you’re aging a hard cheese for months or a soft cheese for weeks, the key lies in precision and patience. The result? A cheese that doesn’t just taste better—it smells like a masterpiece.

Perfect Quesadilla Cheese Amount: Ounces for Ideal Melt and Flavor

You may want to see also

Moisture Loss: Aging reduces water content, concentrating flavors and altering consistency

As cheese ages, it undergoes a natural transformation, and one of the most significant changes is moisture loss. This process is not merely about drying out; it's a delicate dance that intensifies flavors and reshapes texture. Imagine a young, moist cheese like fresh mozzarella, with its high water content (around 50-60%) and mild taste. As it matures, the moisture evaporates, leaving behind a more concentrated, complex flavor profile. For instance, a 6-month-old Parmigiano-Reggiano loses approximately 30% of its original moisture, resulting in a harder texture and a rich, nutty taste that lingers on the palate.

The science behind moisture loss is both simple and fascinating. During aging, cheese is typically stored in controlled environments with specific humidity and temperature levels. These conditions encourage the growth of beneficial molds and bacteria, which break down proteins and fats while simultaneously allowing water to escape. In hard cheeses like Cheddar or Gruyère, this process can reduce moisture content to as low as 30-35%, creating a dense, crumbly texture. Soft cheeses, such as Brie or Camembert, experience a milder version of this transformation, retaining more moisture (around 40-50%) and maintaining their creamy consistency while still developing deeper flavors.

For cheese enthusiasts and home cheesemakers, understanding moisture loss is crucial for achieving desired results. To control this process, consider the aging environment: a cooler, more humid space slows moisture loss, preserving softness, while a warmer, drier setting accelerates it, intensifying flavors and hardening textures. For example, aging a semi-hard cheese like Gouda at 50-55°F (10-13°C) and 85% humidity will yield a smoother texture, whereas 55-60°F (13-15°C) and 80% humidity will produce a firmer, more flavorful cheese. Regularly flipping and brushing the cheese also helps distribute moisture evenly, preventing uneven drying.

The practical implications of moisture loss extend beyond texture and taste. As water content decreases, the cheese becomes less hospitable to unwanted bacteria, extending its shelf life. This is why aged cheeses like Pecorino or aged Gouda can last for months, even years, when properly stored. However, this process requires patience; rushing aging by increasing temperature or reducing humidity can lead to cracks, mold, or off-flavors. For optimal results, follow a gradual aging schedule, monitoring the cheese’s moisture levels and adjusting conditions as needed.

In essence, moisture loss is not a flaw but a feature of the aging process, a key to unlocking a cheese’s full potential. It transforms humble curds into complex, nuanced creations, each slice telling a story of time, craft, and science. Whether you’re a connoisseur or a novice, appreciating this phenomenon deepens your connection to the art of cheesemaking. So, the next time you savor a piece of aged cheese, remember: its concentrated flavor and unique texture are the result of carefully managed moisture loss, a testament to the magic of patience and precision.

Bear Paws Three Cheese Crackers: Peanut-Free Snack or Allergy Risk?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The aging process allows cheese to develop its flavor, texture, and aroma through the breakdown of proteins and fats by bacteria, molds, and enzymes.

Aging causes cheese to become firmer, drier, or crumbly as moisture evaporates and proteins break down, depending on the type of cheese.

Yes, aging intensifies and deepens the flavor of cheese as enzymes and microorganisms transform lactose and proteins into complex compounds.

Rinds form during aging due to the growth of surface molds, bacteria, or through waxing, which protects the cheese and contributes to flavor development.

Aging times vary widely—fresh cheeses may not be aged at all, while hard cheeses like Parmesan can age for over a year to achieve their distinctive characteristics.