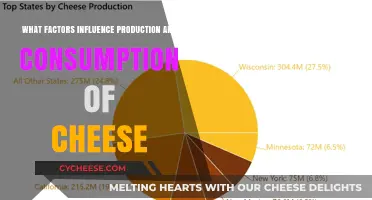

The diverse flavors of cheese are shaped by a combination of factors, including the type of milk used (cow, goat, sheep, or buffalo), the specific breed of the animal, and the animal’s diet, which can impart unique nuances. The cheese-making process itself plays a critical role, with variations in pasteurization, coagulation methods, and the addition of bacterial cultures or molds contributing to distinct taste profiles. Aging time and conditions, such as temperature and humidity, further develop flavors, while regional practices, terroir, and the use of specific techniques or ingredients, like smoking or herbs, add layers of complexity. Together, these elements create the wide array of flavors found in cheeses worldwide.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Milk Source | Cow, Goat, Sheep, Buffalo, Camel. Different animals produce milk with varying fat, protein, and mineral content, affecting flavor. |

| Milk Treatment | Pasteurized, Raw, Thermized. Heat treatment alters milk’s microbial content and enzyme activity, influencing flavor development. |

| Microbial Cultures | Starter cultures (e.g., Lactococcus, Streptococcus), secondary cultures (e.g., Penicillium, Geotrichum). Microbes ferment lactose and produce flavor compounds. |

| Coagulation Method | Rennet (animal or microbial), Acid (e.g., vinegar, lemon juice). Coagulation affects curd formation and texture, impacting flavor. |

| Aging Time | Fresh (e.g., Mozzarella), Semi-soft (e.g., Havarti), Hard (e.g., Parmesan). Longer aging intensifies flavors due to enzymatic and microbial activity. |

| Aging Environment | Temperature, Humidity, Airflow. Controlled environments promote specific mold growth and moisture loss, shaping flavor profiles. |

| Salt Content | Surface salting, Brine immersion, Dry salting. Salt preserves cheese, controls moisture, and enhances or suppresses flavors. |

| Geography | Terroir (soil, climate, local microbes). Regional factors influence milk composition and microbial diversity, creating unique flavors. |

| Additives | Herbs, Spices, Smoke, Wine, Nuts. Added ingredients directly contribute to flavor complexity. |

| Milk Fat Content | Whole milk, Low-fat, Skim. Fat content affects creaminess and the intensity of flavor compounds. |

| Production Method | Artisanal, Industrial. Traditional methods often allow for more complex flavor development due to variability and microbial exposure. |

| pH Level | Acidic, Neutral. pH influences microbial activity and protein structure, affecting flavor and texture. |

| Rind Development | Natural, Washed, Waxed. Rinds host specific microbes and molds that contribute to flavor and protect the cheese. |

| Moisture Content | High (e.g., Fresh cheeses), Low (e.g., Hard cheeses). Moisture levels impact texture and the concentration of flavor compounds. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Milk Source: Cow, goat, sheep, or buffalo milk affects cheese flavor due to fat and protein content

- Aging Process: Longer aging intensifies flavors, creating sharper, more complex tastes in cheese varieties

- Bacteria & Mold: Specific cultures and molds added during production contribute unique flavors and textures

- Region & Climate: Local environment, feed, and traditions influence milk quality and cheese characteristics

- Production Method: Techniques like pasteurization, pressing, and brining alter flavor and consistency

Milk Source: Cow, goat, sheep, or buffalo milk affects cheese flavor due to fat and protein content

The type of milk used in cheese production is a fundamental determinant of its flavor profile, with cow, goat, sheep, and buffalo milk each imparting distinct characteristics. Cow’s milk, the most commonly used, offers a balanced fat (typically 3.5–4%) and protein (around 3.3%) content, resulting in mild, creamy cheeses like Cheddar or Mozzarella. Goat’s milk, with lower fat (3–4%) and higher protein (3.5–4%) levels, produces cheeses with a tangy, slightly acidic flavor, exemplified by Chèvre or Gouda made from goat’s milk. Sheep’s milk, richer in fat (6–8%) and protein (5–6%), yields robust, nutty cheeses such as Manchego or Pecorino Romano. Buffalo milk, with its high fat content (7–8%) and moderate protein (4–5%), creates luxuriously creamy cheeses like Mozzarella di Bufala, known for their rich, buttery mouthfeel.

To understand how milk composition translates to flavor, consider the role of fat and protein. Higher fat content amplifies creaminess and richness, while protein levels influence texture and complexity. For instance, the elevated fat in sheep’s milk contributes to the dense, crumbly texture of Pecorino, while its protein content enhances its savory depth. Conversely, the lower fat in goat’s milk allows its natural acidity to shine, creating a bright, tangy profile. When selecting cheese, note that milk source isn’t just about flavor—it also affects digestibility. Goat and sheep milk, for example, contain smaller fat globules and different protein structures, making them easier to digest for some individuals compared to cow’s milk.

Practical tip: Experiment with cheeses made from the same milk type but different regions or aging processes to isolate the impact of milk source. For instance, compare a young French goat cheese (Chèvre frais) to an aged Dutch goat Gouda. The former highlights the milk’s natural tang, while the latter showcases how aging transforms its flavor. Similarly, taste Mozzarella made from cow’s milk versus buffalo milk side by side to experience how fat content elevates creaminess and richness.

A cautionary note: While milk source is a primary flavor driver, it’s not the sole factor. Other variables like pasteurization, coagulation methods, and aging conditions also play roles. For example, pasteurized goat’s milk may produce a milder cheese compared to raw goat’s milk, which retains more of its natural complexity. However, the baseline flavor profile—tangy, rich, or buttery—remains rooted in the milk’s inherent fat and protein composition.

In conclusion, the choice of milk source acts as a flavor blueprint for cheese, with fat and protein content dictating its core characteristics. Cow’s milk provides versatility, goat’s milk adds brightness, sheep’s milk delivers intensity, and buffalo milk offers opulence. By understanding these distinctions, cheese enthusiasts can better predict and appreciate the flavors they’ll encounter, making informed choices that align with their palate preferences.

Pecorino Romano Cheese: Unveiling Its Iron Content in Grams

You may want to see also

Aging Process: Longer aging intensifies flavors, creating sharper, more complex tastes in cheese varieties

The aging process, or affinage, is a transformative journey for cheese, akin to the maturation of fine wine. During this period, which can range from a few weeks to several years, cheeses develop their distinctive flavors, textures, and aromas. The science behind this lies in the breakdown of proteins and fats by bacteria and enzymes, a process that accelerates with time. For instance, a young cheddar aged for 2 months will have a mild, creamy profile, while one aged for 2 years becomes sharply pungent and crumbly. This evolution is not merely a matter of time but a delicate balance of humidity, temperature, and microbial activity, all of which contribute to the intensity and complexity of the final product.

To understand the impact of aging, consider the difference between fresh mozzarella and aged Parmigiano-Reggiano. The former is aged for just a few days, retaining its soft, milky character, while the latter undergoes a 24-month aging process that concentrates its flavors, resulting in a hard, granular texture and a rich, nutty taste. This transformation is not linear; the first few months often bring out lactic and buttery notes, while longer aging introduces savory, umami, and even caramelized flavors. For home enthusiasts, experimenting with aging times can reveal how a single cheese variety can offer vastly different sensory experiences. A practical tip: store cheese in a cool, humid environment (around 50-55°F and 85% humidity) to mimic professional aging conditions.

Aging also affects the texture of cheese, which in turn influences its flavor perception. Younger cheeses tend to be moist and pliable, allowing their milder flavors to meld smoothly on the palate. As cheese ages, moisture evaporates, and the texture becomes firmer or even crystalline, as seen in aged Gouda. This dryness concentrates flavors, making each bite more pronounced and lingering. For example, a 6-month aged Gruyère will have a slightly grainy texture and a hint of sweetness, while a 12-month version will be harder, with intensified earthy and brothy notes. Pairing aged cheeses with beverages or dishes requires consideration of their intensified profiles; a bold, aged cheddar pairs beautifully with a robust red wine, while a younger, milder version might overwhelm a delicate white.

For those looking to experiment with aging at home, start with hard cheeses like cheddar or gouda, which are more forgiving. Wrap the cheese in cheesecloth or wax paper, place it in a container with a lid, and store it in the refrigerator. Check weekly, adjusting the wrapping if mold appears (some surface mold is normal but can be wiped off with brine). For optimal results, aim for a minimum of 3 months of aging, though 6-12 months will yield more dramatic changes. Keep a journal to track flavor and texture developments, as this will help refine your technique. Remember, aging is both an art and a science, and patience is key to unlocking the full potential of your cheese.

Cheese Sticks and Yogurt: Weight Loss Allies or Diet Myths?

You may want to see also

Bacteria & Mold: Specific cultures and molds added during production contribute unique flavors and textures

The microscopic world of bacteria and mold is a cheese maker's secret weapon, a hidden force that transforms simple milk into a symphony of flavors and textures. These tiny organisms, when carefully selected and introduced during production, become the architects of a cheese's unique character. Imagine a painter's palette, but instead of colors, it's filled with cultures and molds, each contributing distinct notes and sensations.

The Art of Selection: Choosing the right bacteria and mold cultures is a precise science. For instance, *Lactococcus lactis* and *Streptococcus thermophilus* are commonly used starter cultures, responsible for the initial acidification of milk, a crucial step in curd formation. But it's the secondary bacteria and molds that truly differentiate cheeses. *Penicillium camemberti*, when added to the surface of Camembert, creates its signature white rind and creamy interior. In contrast, the blue veins in Stilton are the handiwork of *Penicillium roqueforti*, which imparts a pungent, spicy flavor. The dosage and timing of these additions are critical; a slight variation can lead to vastly different outcomes. For example, a higher concentration of *P. roqueforti* can result in a more intense, sharper flavor, while a lower dose might produce a milder, more subtle taste.

Aging and Transformation: As cheese ages, these microorganisms continue their work, breaking down proteins and fats, releasing enzymes, and creating complex flavor compounds. This process is akin to a slow-motion culinary dance, where time and temperature are key partners. In the case of aged Cheddar, bacteria like *Propionibacterium freudenreichii* produce carbon dioxide gas, creating the characteristic open texture and nutty flavor. The longer the cheese ages, the more pronounced these flavors become. For home cheese makers, controlling temperature and humidity during aging is essential to encourage the desired bacterial activity. A cool, consistent environment, around 50-55°F (10-13°C), is ideal for most cheeses, allowing the cultures to work their magic without spoilage.

Texture and Taste: The impact of bacteria and mold goes beyond flavor. They are instrumental in developing the texture we associate with different cheeses. Soft, creamy cheeses like Brie owe their texture to the action of molds that break down curds, while hard cheeses like Parmesan rely on bacteria to create a dense, crystalline structure. This is where the art of cheese making becomes a delicate balance. Too much bacterial activity can lead to an overly soft or even runny cheese, while too little might result in a dry, crumbly texture. For instance, in the production of Mozzarella, stretching the curd develops its characteristic stringy texture, but it's the specific bacteria cultures that ensure the cheese remains elastic and moist.

In the world of cheese, bacteria and mold are not mere ingredients but master artisans. Their role is a testament to the intricate relationship between microbiology and gastronomy. By understanding and manipulating these microscopic cultures, cheese makers can craft an astonishing array of flavors and textures, turning a simple dairy product into a culinary masterpiece. This section highlights the precision and creativity required in cheese production, where the tiniest organisms have the most significant impact.

Muenster Cheese Slice: Calorie Count and Nutritional Points Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Region & Climate: Local environment, feed, and traditions influence milk quality and cheese characteristics

The terroir of a region—its soil, climate, and local flora—imprints itself on every wheel of cheese produced there. Consider the lush pastures of Normandy, where cows graze on grass rich in alpha-linolenic acid, a compound that contributes to the buttery, nutty flavors of Camembert. In contrast, the arid landscapes of Spain’s Manchego region yield grasses and herbs like thyme and rosemary, which impart earthy, slightly spicy notes to the sheep’s milk cheese. This connection between land and flavor is no coincidence; it’s a direct result of the feed consumed by the animals, which translates into the milk’s chemical composition. For instance, studies show that cows grazing on diverse pastures produce milk with higher levels of conjugated linoleic acid (CLA), a fatty acid linked to richer, more complex flavors in cheese.

To harness this phenomenon, cheesemakers often focus on seasonal variations in feed. In alpine regions like Switzerland, cows are moved to high-altitude pastures in summer, where they consume wildflowers and grasses that contribute to the floral, slightly sweet notes of Gruyère. Conversely, winter feed—typically hay or silage—results in milk with a milder profile. For home cheesemakers or enthusiasts, replicating these flavors requires attention to feed sources. If raising animals isn’t feasible, sourcing milk from local farms with pasture-based practices can yield similar results. For example, using milk from grass-fed cows in a cheddar recipe will produce a sharper, more robust flavor compared to milk from grain-fed animals.

Climate also plays a pivotal role in shaping cheese characteristics, particularly during aging. Humidity, temperature, and microbial environments in a region’s caves or cellars influence rind development and flavor profiles. In the damp, cool caves of France’s Roquefort region, Penicillium roqueforti molds thrive, creating the cheese’s signature blue veins and tangy, pungent flavor. Similarly, the warm, humid cellars of Italy’s Parmigiano-Reggiano producers encourage the growth of beneficial bacteria that contribute to the cheese’s granular texture and savory, umami-rich taste. For those aging cheese at home, mimicking these conditions is key. A wine fridge set to 50–55°F (10–13°C) with 85% humidity can approximate the environment needed for developing complex flavors.

Traditions and local techniques further amplify the influence of region and climate. In the Netherlands, Gouda is often coated in wax, a practice that protects the cheese from the region’s damp climate while allowing it to age slowly. In Mexico, Queso Oaxaca is stretched and braided, a method that adapts to the warm climate by preventing spoilage. These traditions aren’t arbitrary; they’re responses to environmental challenges that have evolved over centuries. For modern cheesemakers, understanding these practices provides a blueprint for innovation. For example, experimenting with natural rinds or using local molds can create unique flavors tied to your specific environment.

Ultimately, the interplay of region, climate, feed, and tradition creates a tapestry of flavors that cannot be replicated elsewhere. This is why a true Parmigiano-Reggiano can only come from Emilia-Romagna, or why a genuine Cheddar must originate in Somerset. For consumers, seeking out cheeses with Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) labels ensures authenticity and supports local traditions. For producers, embracing these factors unlocks the potential to craft cheeses that tell a story of place. Whether you’re a cheesemaker or a connoisseur, recognizing the role of environment in cheese production deepens appreciation for this ancient craft and its enduring connection to the land.

Is the Steak Egg and Cheese Bagel Back on the Menu?

You may want to see also

Production Method: Techniques like pasteurization, pressing, and brining alter flavor and consistency

The transformation of milk into cheese is a delicate dance of science and art, where production methods act as the choreographers shaping flavor and texture. Among these methods, pasteurization, pressing, and brining stand out as pivotal techniques, each leaving its unique imprint on the final product. Consider pasteurization: by heating milk to 161°F (72°C) for 15 seconds or 145°F (63°C) for 30 minutes, this process eliminates harmful bacteria while subtly altering the milk’s protein and enzyme structure. The result? A milder, more consistent flavor profile, as seen in cheeses like mozzarella or cheddar, where pasteurization ensures safety without sacrificing character. However, raw milk cheeses, such as Camembert or Gruyère, retain more complex, earthy notes due to the preservation of native bacteria, highlighting the trade-off between safety and flavor depth.

Pressing, another critical step, determines a cheese’s moisture content and density, directly influencing its texture and taste. Soft cheeses like Brie are barely pressed, retaining up to 50% moisture for a creamy, spreadable consistency. In contrast, hard cheeses such as Parmesan undergo intense pressing, reducing moisture to around 30% and creating a crumbly, crystalline structure. The pressure applied—whether light, medium, or heavy—dictates how whey is expelled, concentrating flavors and proteins. For instance, a semi-hard cheese like Gouda experiences moderate pressing, striking a balance between melt-in-your-mouth creaminess and firm bite. Mastering this technique allows cheesemakers to tailor texture, from velvety to granular, while amplifying or muting specific flavor notes.

Brining, often overlooked, is a flavor and preservation powerhouse. Submerging cheese in a saltwater solution (typically 20–26% salinity) not only slows spoilage but also enhances taste and rind development. Take feta: its signature tang and crumbly texture are achieved through brining, which draws out moisture while infusing saltiness. Similarly, washed-rind cheeses like Limburger owe their pungent aroma to brine washes that encourage bacterial growth. Home cheesemakers can experiment with brining times—2 hours for fresh cheeses, up to 24 hours for aged varieties—to control salt penetration and surface characteristics. However, caution is key: over-brining can lead to an unpalatably salty product, while under-brining risks spoilage.

These techniques, though distinct, intertwine to create cheese’s sensory symphony. Pasteurization sets the stage by stabilizing milk’s foundation, pressing sculpts its physical form, and brining adds the finishing touches. Together, they demonstrate how small adjustments in production yield vast differences in flavor and consistency. For enthusiasts and artisans alike, understanding these methods unlocks the ability to craft cheeses that range from subtly nuanced to boldly assertive. Whether you’re aiming for a delicate chèvre or a robust Pecorino, the secrets lie in mastering these transformative processes.

Moon Cheese at Food Lion: Availability and Shopping Tips

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The type of milk (cow, goat, sheep, or buffalo) significantly influences cheese flavor due to differences in fat content, protein structure, and natural enzymes. For example, goat’s milk tends to produce tangy and earthy flavors, while cow’s milk often results in milder, buttery profiles.

Aging allows enzymes and bacteria to break down proteins and fats, intensifying flavors and developing complex notes. Younger cheeses are milder, while longer-aged cheeses become sharper, nuttier, or even pungent, depending on the variety.

Added ingredients directly contribute to flavor profiles. For instance, blue mold in blue cheese creates a distinct tangy and spicy taste, while herbs and spices like garlic or pepper add specific aromatic and savory notes to the cheese.