Blue cheese is made with mould—specifically, the fungus Penicillium roqueforti. This fungus is added early in the cheesemaking process and produces enzymes that release amino acids, which quickly break down the cheese's proteins. This process, called proteolysis, makes the cheese creamy, especially near the active amino acids in the grey-blue veins. Penicillium roqueforti also triggers another biochemical event called lipolysis, which releases methyl ketone and gives the cheese its distinct blue look, pungent smell, and sharp flavour.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Penicillium roqueforti is the fungus in blue cheese

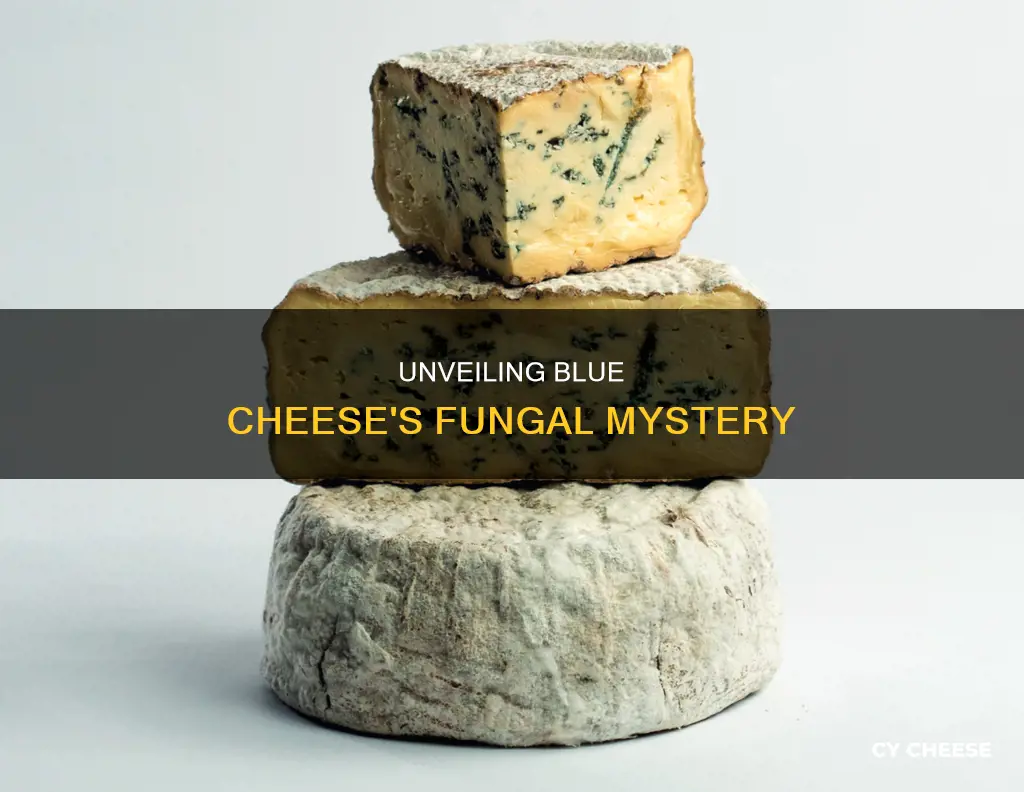

Penicillium roqueforti is a common fungus in the genus Penicillium. It is widespread in nature and can be isolated from soil, decaying organic matter, and plants. This fungus is added to cheese early in the cheesemaking process. During ripening, metal spikes are introduced to create small air-filled passages in the cheese, allowing the fungus to grow and produce blue-green spores that give blue cheese its typical appearance.

P. roqueforti is perhaps best known for its use in the production of blue cheese. It is added as a starter culture during cheese production and is essential to the development of flavour and texture. The growth of the fungus produces volatile and non-volatile flavour components, and it triggers biochemical events that give the cheese its distinct blue look, odd smell, and sharp flavour. P. roqueforti produces enzymes that release amino acids, which quickly break down the cheese's proteins (casein). This process, called proteolysis, makes the cheese creamy, particularly near where the amino acids are most active—the grey, blue veins.

P. roqueforti also triggers another biochemical event called lipolysis, which catalyzes enzymes that lead to the creation of free fatty acids and the release of methyl ketone. This is what gives the cheese its distinct blue look, pungent flavour, and odd smell. The entire world's yearly supply of Roquefort cheese—about 18,000 tons—comes from the small southern French village of the same name.

P. roqueforti is also used in the production of compounds that can be employed as antibiotics, flavours, and fragrances. It has a chitinous texture and is capable of producing harmful secondary metabolites (alkaloids and other mycotoxins) under certain growth conditions. Aristolochene is a sesquiterpenoid compound produced by P. roqueforti, which is likely a precursor to the PR toxin, made in large amounts by the fungus. However, the PR toxin breaks down into the less toxic PR imine in cheese, and the levels of other neurotoxins produced by the fungus are usually too low to be dangerous.

Figs and Blue Cheese: A Perfect Pairing Appetizer

You may want to see also

It's added early in the cheese-making process

The fungus in blue cheese is called Penicillium roqueforti, a common saprotrophic fungus in the genus Penicillium. It is added early in the cheese-making process. Penicillium roqueforti is widespread in nature and can be isolated from soil, decaying organic matter, and plants. It is also used in the production of antifungals, flavouring agents, and antibiotics.

When placed into cream and aerated, P. roqueforti produces a concentrated blue cheese flavouring, a type of enzyme-modified cheese. It produces enzymes that release amino acids, which quickly break down the cheese's proteins (casein). This process, called proteolysis, makes the cheese creamy, particularly near where the amino acids are most active—the grey, blue veins. In addition, P. roqueforti triggers another biochemical event called lipolysis, which leads to the creation of free fatty acids and the release of methyl ketone, giving the cheese its distinct blue look, sharp flavour, and odd smell.

During the 2 to 3 months that the cheese "ages", P. roqueforti also produces between 100 to 200 volatile compounds, particularly methyl ketones, that produce the typical, pungent flavour of blue cheese. The colour in most blue cheeses is created by the blue-green spores that develop as the fungus multiplies. The asexual sporulation of the fungus in the cavities of the cheese results in the characteristic blue-veined appearance.

Recent research has shown significant differences in metabolite production between P. roqueforti populations. The cheese-making populations, particularly the non-Roquefort strains, produce fewer metabolites compared to non-cheese populations found in lumber and silage. The non-cheese populations maintain higher metabolite diversity, particularly in fatty acids and terpenoids, which may provide competitive advantages in more complex environments where fungi must compete with other microorganisms.

The Evolution of Blue Cheese: A Cheese Odyssey

You may want to see also

It produces enzymes that break down cheese proteins

The fungus in blue cheese is called Penicillium roqueforti, a common saprotrophic fungus in the genus Penicillium. It is widespread in nature and can be isolated from soil, decaying organic matter, and plants. The major industrial use of this fungus is the production of blue cheeses, flavouring agents, antifungals, polysaccharides, proteases, and other enzymes.

P. roqueforti produces enzymes that break down cheese proteins through a process called proteolysis. This process releases amino acids, which quickly break down the cheese's proteins (casein). This process makes the cheese creamy, particularly near where the amino acids are most active—the grey, blue veins.

In addition to proteolysis, P. roqueforti also triggers another biochemical event called lipolysis, which catalyzes enzymes that lead to the creation of free fatty acids and the release of methyl ketone. This gives the cheese its distinct blue look, odd smell, and sharp flavour.

The entire world's yearly supply of Roquefort cheese—about 18,000 tons—comes from the small southern French village of the same name. The process of making this cheese has been refined over the centuries since its discovery, which is attributed to a shepherd who left his lunch of rye bread and sheep's milk cheese in a cave for several months. Upon returning, the shepherd found his lunch covered in a thick layer of P. roqueforti mold and decided to eat it anyway. Fortunately, this particular mold is not only safe for human consumption but may also have health benefits.

Cheese Choices for Cordon Bleu Perfection

You may want to see also

Explore related products

It's also used to make flavouring agents and antibiotics

The fungus that is intentionally added to blue cheese is called Penicillium. This genus of fungi is also used in many other applications, including the creation of flavouring agents and antibiotics.

Penicillium plays a key role in the production of

The Perfect Blue Stilton Platter: A Guide to Serving

You may want to see also

It's found in the Roquefort, Stilton, and Gorgonzola cheeses

The fungus found in Roquefort, Stilton, and Gorgonzola cheeses is called Penicillium roqueforti. It is a common saprotrophic fungus in the genus Penicillium and is widespread in nature, isolated from sources such as soil, decaying organic matter, and plants. The fungus is added early in the cheesemaking process and is responsible for the distinctive blue veins in these cheeses. During the ageing process, which takes 2 to 3 months, metal spikes are inserted to create small air-filled passages for the fungus to grow and produce blue-green spores.

P. roqueforti is also known for its role in flavour and texture development. It produces between 100 to 200 volatile compounds, particularly methyl ketones, that contribute to the pungent flavour of blue cheese. The fungus also produces enzymes that soften the curd and develop the desired body and texture of the cheese. Additionally, P. roqueforti has been used to produce flavouring agents, antifungals, polysaccharides, proteases, and other enzymes.

While P. roqueforti is generally safe for consumption, some strains can produce harmful secondary metabolites, such as alkaloids and mycotoxins, under certain growth conditions. One such mycotoxin is the PR toxin, which has been linked to incidents of mycotoxicoses from consuming contaminated grains. However, in the context of cheese, the PR toxin breaks down into the less toxic PR imine, and the levels of other neurotoxins like roquefortine C are typically too low to cause toxic effects.

The colour of blue cheese has recently gained attention, with researchers successfully altering the genes responsible for the blue hue without affecting flavour or increasing toxin levels. This discovery opens up the possibility of creating blue cheeses in different colours, such as red, green, or white, while retaining the iconic taste of varieties like Roquefort, Stilton, and Gorgonzola.

Safeway's Wishbone Light Blue Cheese Dressing: Where to Find It

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The fungus in blue cheese is called Penicillium roqueforti.

Penicillium roqueforti produces enzymes that release amino acids, which quickly break down the cheese's proteins (casein). This process, called proteolysis, makes the cheese creamy, especially near where the amino acids are most active — the gray, blue veins.

Yes, the fungus is safe to eat. While the PR toxin produced by the fungus can be harmful under certain growth conditions, it breaks down into the less toxic PR imine in cheese.