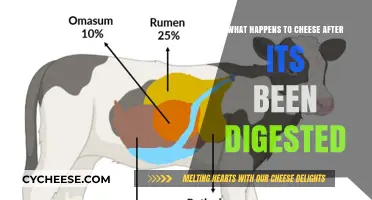

When lactase, an enzyme that breaks down lactose (milk sugar), is added to cheese, it primarily affects cheeses that contain residual lactose. Most aged cheeses naturally have low lactose levels due to the fermentation process, where bacteria consume lactose to produce lactic acid. However, in fresher or softer cheeses with higher lactose content, adding lactase can hydrolyze lactose into simpler sugars (glucose and galactose), reducing its concentration. This process can make the cheese more digestible for lactose-intolerant individuals, as lactose is the primary trigger for their digestive discomfort. Additionally, the breakdown of lactose may subtly alter the cheese’s texture and flavor, potentially making it sweeter due to the release of simple sugars.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Lactose Breakdown | Lactase enzyme breaks down lactose (milk sugar) into simpler sugars: glucose and galactose. |

| Reduced Lactose Content | Significantly lowers lactose levels in cheese, making it more tolerable for lactose intolerant individuals. |

| Improved Digestibility | Easier digestion due to reduced lactose, leading to fewer gastrointestinal symptoms like bloating, gas, and diarrhea. |

| Altered Texture | May become slightly softer or creamier due to the breakdown of lactose and potential changes in moisture content. |

| Flavor Changes | Can develop a sweeter taste due to the presence of glucose and galactose. |

| Shelf Life | Potentially shorter shelf life due to increased susceptibility to bacterial growth from the broken-down sugars. |

| Applications | Used in producing lactose-free or reduced-lactose cheeses for lactose intolerant consumers. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Lactase breaks down lactose in cheese, reducing its presence and altering texture and taste

- Cheese with added lactase becomes more digestible for lactose-intolerant individuals

- Lactase addition can speed up cheese aging by modifying lactose content

- Flavor changes occur as lactose breakdown affects microbial activity in cheese

- Texture becomes softer or crumbly due to lactose reduction in cheese structure

Lactase breaks down lactose in cheese, reducing its presence and altering texture and taste

Lactase, an enzyme that breaks down lactose into simpler sugars (glucose and galactose), plays a transformative role when added to cheese. In raw milk, lactose is a primary carbohydrate, but during cheesemaking, bacteria convert much of it into lactic acid. However, residual lactose often remains, particularly in fresher cheeses like mozzarella or cottage cheese. When lactase is introduced, it accelerates the breakdown of this remaining lactose, significantly reducing its concentration. This enzymatic action is especially useful for creating low-lactose or lactose-free cheese products, catering to individuals with lactose intolerance.

The process of adding lactase to cheese is both a science and an art. Typically, lactase is added in liquid or powdered form during the cheese-making process, with dosages ranging from 0.05% to 0.2% of the milk’s weight, depending on the desired lactose reduction. For example, in a 100-liter batch of milk, 50–200 grams of lactase might be used. The enzyme works most effectively at temperatures between 40–45°C (104–113°F) and requires time—often 24 to 48 hours—to fully hydrolyze lactose. This step is crucial for ensuring the final product meets lactose-free standards, typically defined as less than 0.1% lactose content.

The impact of lactase on cheese texture and taste is subtle yet significant. As lactose breaks down into glucose and galactose, the cheese becomes slightly sweeter, as these simple sugars are more perceptible to the palate. Simultaneously, the reduction in lactose alters the cheese’s moisture content and structure. Fresher cheeses may become softer or more crumbly due to the loss of lactose’s binding properties, while harder cheeses might retain their texture but gain a smoother mouthfeel. For instance, lactase-treated cheddar often exhibits a creamier profile compared to its untreated counterpart.

Practical applications of lactase in cheesemaking extend beyond lactose intolerance solutions. Artisanal cheesemakers use lactase to experiment with flavor profiles, creating unique products that appeal to broader audiences. For home cheesemakers, adding lactase is straightforward: dissolve the enzyme in warm water and mix it into the milk before coagulation. However, caution is advised—overuse of lactase can lead to excessive sweetness or textural instability. Monitoring pH levels during the process ensures the cheese develops properly, as the breakdown of lactose can slightly alter acidity.

In summary, lactase’s role in cheese is twofold: it reduces lactose content for dietary inclusivity and subtly enhances sensory qualities. By understanding dosage, timing, and temperature, cheesemakers can harness this enzyme to craft products that are both accessible and delightful. Whether for commercial production or home experimentation, lactase offers a versatile tool for innovating in the world of cheese.

Mastering the BL2 Raid Boss: Easy Cheesing Strategies Revealed

You may want to see also

Cheese with added lactase becomes more digestible for lactose-intolerant individuals

Lactose intolerance affects millions worldwide, making dairy consumption a challenge. However, adding lactase to cheese during production breaks down lactose into simpler sugars, glucose and galactose, which are easily absorbed without triggering digestive discomfort. This enzymatic process transforms cheese into a more digestible option for those with lactose intolerance, allowing them to enjoy dairy without the usual side effects.

Consider the practical application: lactase is typically added in precise dosages, often 0.05–0.1% of the cheese’s weight, during the brining or mixing stages. For aged cheeses like cheddar or Swiss, lactase can be incorporated before aging, ensuring lactose breakdown over time. Soft cheeses like mozzarella or cream cheese may require direct lactase addition post-production. Manufacturers often label these products as "lactose-free" or "lactase-treated," providing clarity for consumers. For homemade experiments, lactase drops or tablets can be dissolved in water and mixed into cheese recipes, though results may vary based on cheese type and lactase concentration.

From a comparative standpoint, lactase-treated cheese offers a middle ground between traditional dairy and plant-based alternatives. While lactose-free cheese retains the flavor and texture of conventional cheese, it avoids the processed taste often associated with vegan substitutes. For instance, a lactase-treated cheddar maintains its sharp, tangy profile while becoming accessible to lactose-intolerant individuals. This approach preserves the sensory experience of dairy without compromising digestibility, making it a superior option for those reluctant to switch to non-dairy alternatives.

A critical takeaway is that lactase-treated cheese is not entirely lactose-free but contains significantly reduced levels, typically below 0.1 grams per serving. This threshold is generally tolerable for most lactose-intolerant individuals, though sensitivity varies. For severe cases, consulting a dietitian is advisable to determine safe consumption limits. Pairing lactase-treated cheese with probiotic-rich foods like yogurt or kefir can further enhance digestion by supporting gut health. With proper awareness and moderation, this innovation allows dairy lovers to reclaim their favorite cheeses without fear of discomfort.

Caring for Your Bamboo Cheese Board: Essential Tips for Longevity

You may want to see also

Lactase addition can speed up cheese aging by modifying lactose content

Lactase, the enzyme responsible for breaking down lactose, plays a pivotal role in accelerating the aging process of cheese when added deliberately. By hydrolyzing lactose into glucose and galactose, lactase reduces the cheese’s lactose content, which is particularly beneficial for producing harder, aged cheeses. This enzymatic action mimics the natural breakdown that occurs during aging but at an expedited rate. For instance, in cheddar production, adding lactase at a dosage of 0.05–0.1% (based on milk weight) can significantly shorten the aging time from 6–12 months to just 3–6 months, while maintaining desired texture and flavor profiles.

The mechanism behind this acceleration lies in how lactose influences moisture retention and microbial activity. Lactose naturally binds water, keeping cheese moist during aging. When lactase reduces lactose levels, less water is retained, leading to a drier curd more conducive to rapid aging. Additionally, the resulting glucose and galactose serve as readily available energy sources for lactic acid bacteria, which produce acids and flavor compounds faster. This dual effect—moisture reduction and microbial stimulation—creates an environment where cheese matures more quickly without sacrificing quality.

Practical application of lactase in cheesemaking requires precision. Dosage must be tailored to the cheese variety and desired aging timeline. For semi-hard cheeses like Gouda, a lower lactase concentration (0.03%) may suffice, while harder cheeses like Parmesan benefit from higher doses (up to 0.15%). Monitoring pH and moisture levels during aging is critical, as excessive lactase can lead to over-acidification or crumbly texture. Pairing lactase with controlled temperature and humidity ensures the cheese ages uniformly, preserving its structural integrity.

Comparatively, traditional aging methods rely on time and natural lactose breakdown, which can be unpredictable and resource-intensive. Lactase addition offers a controlled, cost-effective alternative, especially for artisanal producers seeking to scale production. However, it’s essential to balance speed with tradition; over-reliance on lactase may strip cheese of its unique, time-honored characteristics. For optimal results, combine lactase with partial natural aging, allowing the cheese to develop complexity while benefiting from reduced maturation time.

In summary, lactase addition is a strategic tool for cheesemakers aiming to streamline aging without compromising quality. By modifying lactose content, it accelerates moisture loss and microbial activity, shaving months off traditional timelines. With careful dosage and monitoring, this technique bridges innovation and tradition, offering a practical solution for modern cheesemaking demands. Whether crafting aged cheddar or experimental varieties, lactase empowers producers to achieve maturity faster, meeting market needs while retaining artisanal excellence.

Ricotta Cheese and Lactose: Understanding Its Content and Impact

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$31.95

Flavor changes occur as lactose breakdown affects microbial activity in cheese

Lactase, an enzyme that breaks down lactose into simpler sugars (glucose and galactose), significantly alters the flavor profile of cheese by influencing microbial activity. When added to cheese, lactase accelerates lactose hydrolysis, reducing its concentration in the matrix. This shift in sugar availability directly impacts the metabolic pathways of lactic acid bacteria (LAB) and other microorganisms responsible for flavor development. For instance, in young cheeses like mozzarella or fresh cheddar, lactase addition can lead to rapid acidification due to increased glucose and galactose fermentation, resulting in a sharper, tangier flavor within days.

Consider the practical application in aged cheeses, where lactase is often used to make them more digestible for lactose-intolerant consumers. In a 10 kg batch of cheddar, adding 0.1% lactase by weight (10 g) can reduce lactose content by up to 90% within 24 hours. However, this rapid breakdown limits the substrate available for slow-acting flavor-producing microbes, such as *Penicillium* molds in blue cheese. The result? A milder, less complex flavor profile compared to untreated counterparts. This trade-off highlights the delicate balance between digestibility and sensory quality.

To mitigate flavor loss, cheesemakers can employ a staged approach. Start by adding lactase during the final stages of aging, allowing residual lactose to contribute to flavor development earlier in the process. For example, in a 6-month aged Gouda, introduce lactase only in the last 2 months. Alternatively, blend treated and untreated batches to retain complexity while reducing lactose content. Dosage precision is critical; exceeding 0.2% lactase can lead to excessive sweetness from unfermented sugars, overpowering subtler notes.

The microbial community’s response to lactase addition varies by cheese type. In semi-soft cheeses like Brie, where *Penicillium camemberti* drives flavor, lactase-induced sugar changes can enhance surface mold activity, yielding a richer, earthy aroma. Conversely, in hard cheeses like Parmesan, where slow acidification is key, premature lactose breakdown may result in a flat, one-dimensional taste. Monitoring pH and sugar levels post-addition is essential to adjust aging conditions and preserve desired characteristics.

Ultimately, understanding the interplay between lactase, lactose breakdown, and microbial metabolism empowers cheesemakers to innovate without sacrificing flavor. For home enthusiasts experimenting with lactase, start with a 0.05% dosage in soft cheeses and observe changes over 48 hours. Commercial producers should invest in real-time lactose testing to fine-tune applications. While lactase offers digestibility benefits, its use demands strategic planning to ensure flavor remains the star of the cheese board.

Understanding Cheese Brick Weights: How Many Grams Are in One?

You may want to see also

Texture becomes softer or crumbly due to lactose reduction in cheese structure

Lactase, an enzyme that breaks down lactose into simpler sugars, significantly alters the texture of cheese when added. This transformation occurs because lactose, a milk sugar, plays a structural role in cheese, binding moisture and contributing to its firmness. When lactase reduces lactose content, the cheese’s moisture balance shifts, leading to either a softer or crumblier texture depending on the cheese type and lactase dosage. For instance, adding 0.1–0.5% lactase by weight to a semi-hard cheese like Cheddar can result in a noticeably softer interior within 2–4 weeks of aging, as lactose breakdown releases water molecules previously trapped in the matrix.

To achieve a softer texture intentionally, consider applying lactase during the cheese-making process rather than post-production. For fresh cheeses like mozzarella or ricotta, incorporating lactase at a rate of 0.05–0.2% during curdling can yield a creamier mouthfeel without excessive crumbling. However, caution is necessary: over-application of lactase (above 0.5%) can lead to excessive moisture release, causing the cheese to become unpleasantly mushy or prone to spoilage due to increased water activity. Always monitor pH and moisture levels during aging to ensure the desired texture is achieved without compromising shelf life.

The crumblier texture, often desirable in aged cheeses like Parmesan or feta, emerges when lactase activity progresses further, breaking down lactose to the point where the protein matrix weakens. This effect is particularly pronounced in low-moisture cheeses, where lactose reduction disrupts the tight protein network. For example, treating aged Gouda with 0.3% lactase for 6–8 weeks can enhance its crumbly, granular quality, making it ideal for grating or sprinkling. Pairing lactase treatment with controlled humidity (around 85%) during aging can amplify this effect by preventing excessive drying while allowing lactose breakdown to proceed.

Practical tips for home cheesemakers include using lactase in powdered form for even distribution and starting with small test batches to calibrate dosage. For softer cheeses, apply lactase early in the process and monitor texture weekly; for crumbly results, allow longer aging periods and maintain consistent temperature (10–12°C) to encourage gradual lactose breakdown. Remember, the goal is to balance lactose reduction with moisture retention—too little lactase yields minimal effect, while too much risks structural collapse. By understanding this interplay, cheesemakers can harness lactase to craft textures tailored to specific culinary applications.

Vegan Cheese at Pieology River Center: Availability and Options

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

When lactase is added to cheese, it breaks down lactose (milk sugar) into simpler sugars, glucose and galactose. This process reduces the lactose content, making the cheese more tolerable for individuals with lactose intolerance.

Adding lactase typically does not significantly alter the taste or texture of cheese. However, the slight breakdown of lactose into simpler sugars may impart a subtly sweeter flavor in some cases.

Yes, lactase can be added to any type of cheese, but its effectiveness depends on the cheese's lactose content. Fresh cheeses like mozzarella or ricotta, which have higher lactose levels, will show more noticeable changes compared to aged cheeses like cheddar or Parmesan, which naturally contain very little lactose.