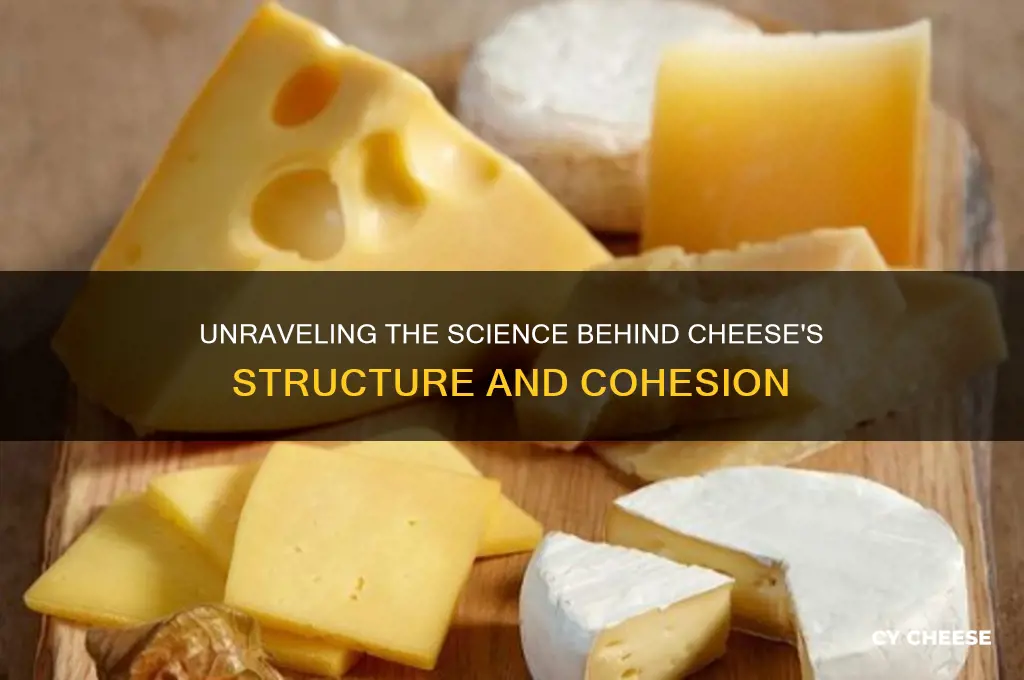

Cheese, a beloved dairy product with a rich history and diverse varieties, is held together by a complex interplay of proteins, fats, and moisture. The primary structural component is casein, a group of milk proteins that coagulate during the cheesemaking process, forming a network that traps fat and water molecules. This network is further strengthened by the action of rennet or other coagulating agents, which cause the casein micelles to bond together, creating a semi-solid mass. Additionally, the aging process plays a crucial role, as enzymes break down proteins and fats, altering the texture and contributing to the cheese's overall cohesion. Understanding these mechanisms not only sheds light on the science behind cheese but also highlights the artistry involved in crafting its myriad forms.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Protein Matrix | Casein proteins (primarily αs1-, αs2-, β-, and κ-casein) form a network through aggregation and micelle structures. |

| Fat Content | Fat globules dispersed within the protein matrix contribute to texture and structure. |

| Moisture Content | Water binds to casein proteins and affects cheese consistency (higher moisture = softer cheese). |

| Calcium Ions (Ca²⁺) | Stabilize casein micelles by cross-linking proteins, crucial for structure. |

| pH Level | Lower pH (more acidic) during curdling promotes casein precipitation and aggregation. |

| Enzymatic Action | Rennet or microbial enzymes (e.g., chymosin) cleave κ-casein, destabilizing micelles and enabling curd formation. |

| Salt | Enhances protein matrix strength by reducing moisture and stabilizing casein interactions. |

| Microbial Activity | Bacteria (e.g., lactic acid bacteria) produce acids and enzymes that influence curd formation and texture. |

| Heat Treatment | Applied during processing to denature proteins and strengthen the matrix. |

| Pressure/Stretching | Mechanical processes (e.g., stretching in mozzarella) align proteins and improve cohesion. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Milk Proteins: Casein proteins coagulate, forming a network that binds cheese curds together during production

- Enzymes: Rennet or microbial enzymes clot milk, initiating curd formation and structure development

- Moisture Content: Water expulsion during pressing determines density and cohesion in cheese texture

- Salt Role: Salt draws out moisture, tightens protein bonds, and strengthens the cheese matrix

- Aging Process: Microbial activity and enzyme breakdown during aging enhance protein bonding and texture

Milk Proteins: Casein proteins coagulate, forming a network that binds cheese curds together during production

Cheese, a culinary marvel, owes its structure to a fascinating process centered on milk proteins, specifically casein. These proteins, comprising about 80% of milk's protein content, play a pivotal role in cheese production. When milk is acidified or exposed to rennet, casein proteins undergo a transformation: they coagulate, forming a complex network that traps fat and other milk components, resulting in the formation of cheese curds. This natural process is the foundation of cheese-making, turning liquid milk into a solid, sliceable delight.

The Coagulation Process: A Delicate Balance

Coagulation is not a random event but a precise chemical reaction. Rennet, an enzyme complex, hydrolyzes κ-casein, removing its stabilizing effect and allowing other casein proteins to aggregate. This aggregation is temperature-sensitive, typically occurring between 28°C and 35°C (82°F to 95°F). For home cheese-makers, maintaining this temperature range is critical. Too low, and coagulation slows; too high, and the curd may become tough. Adding 1/4 teaspoon of rennet to a gallon of milk is a common starting point, though adjustments depend on milk type and desired cheese texture.

Casein’s Network: Strength in Structure

Once coagulated, casein proteins form a gel-like matrix that binds curds together. This network is both flexible and strong, allowing cheese to hold its shape while remaining sliceable. The density of this network determines cheese texture: a tighter network yields harder cheeses like cheddar, while a looser one results in softer varieties like mozzarella. Understanding this structure empowers cheese-makers to manipulate variables like pH, temperature, and rennet dosage to achieve specific outcomes. For instance, lowering pH accelerates coagulation, ideal for quick-setting cheeses like ricotta.

Practical Tips for Optimal Coagulation

For those crafting cheese at home, precision is key. Use a thermometer to monitor milk temperature, and avoid stirring excessively once rennet is added, as this can weaken the curd. If using acid (like lemon juice) instead of rennet, add it gradually while stirring gently until the milk separates into curds and whey. For harder cheeses, press the curds under weights to expel whey and tighten the casein network. Experimenting with different milk types (cow, goat, sheep) can also yield unique textures, as their casein structures vary slightly.

The Takeaway: Casein’s Role in Cheese Unity

Casein’s coagulation is the unsung hero of cheese-making, transforming milk into a cohesive, edible masterpiece. By mastering this process, cheese-makers can control texture, flavor, and structure, turning a simple ingredient into a diverse array of culinary delights. Whether crafting a creamy brie or a sharp parmesan, the casein network remains the binding force that holds cheese together, both literally and figuratively.

Should Block Cheese Be Refrigerated? Storage Tips for Freshness

You may want to see also

Enzymes: Rennet or microbial enzymes clot milk, initiating curd formation and structure development

Enzymes play a pivotal role in transforming milk into cheese, acting as the catalysts that initiate curd formation and structure development. Among these, rennet and microbial enzymes are the most commonly used. Rennet, derived from the stomach lining of ruminant animals, contains chymosin, an enzyme that specifically cleaves kappa-casein, a protein in milk, causing it to coagulate. Microbial enzymes, on the other hand, are produced by bacteria or fungi and offer a vegetarian-friendly alternative. Both types of enzymes achieve the same goal: converting liquid milk into a solid mass by clotting proteins, but their sources, specificity, and applications differ significantly.

To use rennet effectively, precise dosage is critical. Typically, 1/4 to 1/2 teaspoon of liquid rennet diluted in cool, non-chlorinated water is added per 2 gallons (8 liters) of milk. This mixture should be stirred gently for a few seconds to ensure even distribution. The milk is then left undisturbed at a controlled temperature (usually 86–100°F or 30–38°C) for 30–60 minutes, depending on the recipe. Overuse of rennet can result in a bitter taste or excessively firm curds, while underuse may lead to weak curds that fail to hold together. For microbial enzymes, follow the manufacturer’s instructions, as dosages can vary widely based on the product’s concentration.

Microbial enzymes offer versatility, particularly for vegetarian or organic cheese production. They are often preferred in soft cheeses like mozzarella or fresh cheeses like paneer, where a milder coagulation is desired. However, they may not always match the firmness achieved with rennet, making them less ideal for hard cheeses like cheddar. When substituting microbial enzymes for rennet, experiment with dosages and observe curd formation closely. For example, a common microbial enzyme blend might require 1/2 to 1 teaspoon per 2 gallons of milk, but this can vary based on the enzyme’s activity level.

The choice between rennet and microbial enzymes also depends on the desired texture and flavor profile. Rennet-coagulated cheeses often have a cleaner, sharper flavor and a more elastic texture, making them suitable for aged varieties. Microbial enzymes, however, can introduce subtle flavor nuances due to the metabolic byproducts of the microorganisms involved. For home cheesemakers, starting with rennet for traditional recipes and experimenting with microbial enzymes for innovative creations can provide a deeper understanding of how enzymes shape cheese characteristics.

In conclusion, enzymes are the unsung heroes of cheese making, driving the transformation from liquid milk to solid curds. Whether using rennet or microbial enzymes, precision in dosage and attention to temperature are key to achieving the desired structure and flavor. By mastering these tools, cheesemakers can control the outcome, crafting cheeses that range from delicate and creamy to firm and complex. Understanding the role of enzymes not only demystifies the cheese-making process but also empowers experimentation and creativity in the craft.

Is Raw Milk Cheese Legal in the US? What You Need to Know

You may want to see also

Moisture Content: Water expulsion during pressing determines density and cohesion in cheese texture

The amount of water expelled during pressing is a critical factor in determining the final texture of cheese. This process, known as syneresis, directly influences the density and cohesion of the curd, shaping the cheese's mouthfeel and structural integrity. Harder cheeses like Parmesan or Cheddar undergo more aggressive pressing, expelling a higher percentage of moisture (up to 50-60% of their weight) compared to softer cheeses like Brie or Camembert, which retain more water (around 40-50%). This variation in moisture content is a primary reason why a slice of Cheddar crumbles differently than a wedge of Brie spreads.

Understanding this relationship allows cheesemakers to precisely control texture by adjusting pressing time, pressure, and temperature during production.

Imagine pressing a sponge: the firmer you squeeze, the denser it becomes. Cheese curds behave similarly. During pressing, the curd's protein matrix tightens as water is expelled, forcing the proteins closer together. This increased protein density creates a firmer, more cohesive structure. For example, a young Cheddar pressed for 12-18 hours at 30-40 psi will have a tighter, more crumbly texture than one pressed for only 6 hours at 20 psi. Controlling pressing parameters allows cheesemakers to fine-tune the desired texture, from a flaky, open-textured cheese to a dense, sliceable one.

A crucial consideration is the curd's initial moisture content. Curds with higher moisture require longer pressing times or higher pressures to achieve the same density as drier curds. This highlights the interconnectedness of various cheese-making steps, as factors like coagulation time and cutting technique also influence initial moisture levels.

While pressing is essential for moisture expulsion, it's not the sole determinant of texture. The type of milk, starter cultures, and aging process all play significant roles. For instance, cheeses made with thermophilic bacteria tend to be firmer due to the production of lactic acid, which strengthens the protein matrix. However, without proper pressing to remove excess moisture, even these cheeses would lack the desired density and cohesion. Understanding the interplay between moisture content, pressing, and other factors empowers cheesemakers to craft cheeses with specific textural profiles, from creamy and spreadable to hard and grateable.

Does String Cheese Cause Acne? Unraveling the Dairy-Skin Connection

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$14.85

$14.85

Salt Role: Salt draws out moisture, tightens protein bonds, and strengthens the cheese matrix

Salt is the unsung hero in the intricate process of cheese making, playing a pivotal role in shaping the final product's texture and structure. Its primary function is threefold: drawing out moisture, tightening protein bonds, and fortifying the cheese matrix. When added to curds, salt initiates a process known as syneresis, where it draws moisture out of the cheese, concentrating the proteins and fats. This dehydration is crucial for creating a firmer texture, as seen in cheeses like cheddar or Parmesan, where salt is added directly to the curds or during brining. The amount of salt used is critical; typically, 1-3% of the cheese's weight is added, depending on the desired outcome. Too little salt can result in a soft, unstable cheese, while too much can overpower the flavor and inhibit proper aging.

The tightening of protein bonds is another essential function of salt in cheese making. Proteins in milk, particularly casein, form a network that holds the cheese together. Salt acts as a bridge between these proteins, strengthening their bonds and creating a more cohesive structure. This process is particularly evident in hard cheeses, where the curds are heated and pressed, and salt is added to enhance the protein matrix. For example, in the production of Swiss cheese, salt is carefully measured and added to ensure the proteins form a tight, resilient network that can withstand the development of large eyes (holes) during aging. Without salt, the protein bonds would remain weak, leading to a crumbly or overly soft texture.

Strengthening the cheese matrix is perhaps salt's most transformative role. By reducing moisture content and tightening protein bonds, salt creates a stable environment that resists spoilage and supports the aging process. This is especially important in aged cheeses, where the matrix must remain intact over months or even years. For instance, in the production of Gouda, salt is added in precise amounts (around 2% of the cheese's weight) to ensure the matrix can withstand the long aging process, resulting in a cheese that is both firm and flavorful. The matrix's strength also affects the cheese's ability to slice, melt, and maintain its shape, making salt a key determinant of the final product's functionality.

Practical application of salt in cheese making requires attention to timing and method. Salt can be added directly to the curds, mixed in during milling, or applied through brining. Direct salting is common in hard cheeses, where the salt is evenly distributed throughout the curds before pressing. Brining, on the other hand, is often used for semi-soft cheeses like mozzarella or feta, where the cheese is submerged in a saltwater solution to absorb salt gradually. Home cheese makers should note that the type of salt matters; non-iodized salt is preferred, as iodine can affect flavor and texture. Additionally, monitoring the cheese's moisture content during salting is crucial, as over-salting can lead to a dry, unpalatable product.

In summary, salt's role in cheese making is both complex and indispensable. By drawing out moisture, tightening protein bonds, and strengthening the cheese matrix, it transforms a simple mixture of curds into a structured, durable, and flavorful product. Understanding the precise application of salt—whether in dosage, timing, or method—allows cheese makers to control texture, aging potential, and overall quality. From the crumbly bite of a well-salted feta to the smooth melt of a perfectly brined mozzarella, salt is the silent architect behind every great cheese.

Biblical Dairy: Does the Bible Mention Butter or Cheese?

You may want to see also

Aging Process: Microbial activity and enzyme breakdown during aging enhance protein bonding and texture

The aging of cheese is a transformative journey where time, microbes, and enzymes collaborate to create a complex structure and flavor profile. During this process, microbial activity and enzyme breakdown play pivotal roles in enhancing protein bonding and texture, turning a simple curd into a sophisticated cheese. Lactic acid bacteria, molds, and yeasts metabolize lactose and proteins, releasing enzymes that break down casein—the primary protein in milk. This breakdown allows for the formation of stronger bonds between protein molecules, resulting in a firmer, more cohesive texture. For instance, in aged cheddar, the activity of proteolytic enzymes over months or even years creates a crumbly yet tightly bound interior, a stark contrast to its younger, softer counterparts.

Consider the step-by-step process of how this transformation occurs. Initially, cheese curds are rich in moisture and loosely structured proteins. As aging begins, microbes like *Penicillium camemberti* in Camembert or *Propionibacterium freudenreichii* in Swiss cheese produce enzymes that cleave casein into smaller peptides and amino acids. This enzymatic action reduces water content and increases protein-protein interactions, tightening the cheese matrix. Temperature and humidity control are critical here—ideally, aging rooms maintain 50–55°F (10–13°C) and 85–95% humidity to optimize microbial activity without promoting spoilage. Too high a temperature accelerates enzyme activity, risking over-softening, while too low a temperature stalls the process entirely.

A comparative analysis highlights how different cheeses leverage microbial activity and enzyme breakdown uniquely. Hard cheeses like Parmigiano-Reggiano age for 12–36 months, during which lipases break down fats and proteases enhance protein bonding, resulting in a granular yet unified texture. In contrast, semi-soft cheeses like Gruyère rely on propionic acid bacteria to create eyes (holes) while maintaining structural integrity through moderate enzyme activity. Blue cheeses, such as Roquefort, showcase a dramatic interplay of *Penicillium roqueforti* mold and proteases, creating a creamy yet crumbly texture with distinct veins. Each cheese type demonstrates how tailored microbial and enzymatic processes dictate texture and cohesion.

Practical tips for home cheesemakers emphasize the importance of patience and precision in aging. For beginners, start with a semi-hard cheese like Gouda, aging it for 2–6 months at controlled conditions. Use a wine fridge or a cool basement, ensuring consistent temperature and humidity. Regularly flip the cheese to prevent moisture accumulation on one side, which can lead to uneven enzyme activity. For advanced makers, experiment with surface molds by introducing *Penicillium candidum* spores to create a bloomy rind like Brie. Monitor pH levels—a drop from 5.5 to 5.0 indicates active microbial metabolism, signaling optimal aging conditions. Remember, aging is as much art as science; small adjustments yield significant textural differences.

In conclusion, the aging process is a delicate dance of microbial activity and enzyme breakdown that strengthens protein bonding and refines texture. By understanding the mechanisms at play—from enzyme specificity to environmental control—cheesemakers can craft products with desired characteristics. Whether producing a firm, crystalline Parmesan or a creamy, veined blue cheese, the principles remain consistent: time, microbes, and enzymes are the architects of cheese cohesion. Master these, and the possibilities are as boundless as the varieties of cheese themselves.

Mastering Trials of Osiris: Easy Cheese Strategies for Destiny 2 Wins

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Cheese is held together by a network of proteins, primarily casein, which coagulates during the cheesemaking process. This network traps fat and moisture, creating the cheese's structure.

Rennet, an enzyme, breaks down casein proteins into a gel-like structure, causing the milk to curdle. This curd formation is essential for holding cheese together during and after production.

Yes, fat acts as a binder within the protein matrix, contributing to the cheese's texture and cohesion. Higher fat content often results in a creamier, more cohesive cheese.

The type of milk, aging process, moisture content, and production techniques (e.g., pressing or heating) determine how well a cheese holds together. Harder cheeses are typically more cohesive due to lower moisture and longer aging.