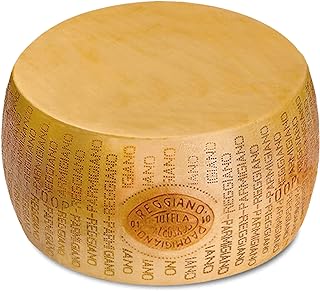

When discussing large quantities of cheese, the term wheel is commonly used to describe a big unit, particularly for varieties like cheddar, Parmesan, or Gouda. These wheels can vary significantly in size, often weighing anywhere from 20 to 100 pounds or more, depending on the type of cheese and the traditions of the region where it is produced. For instance, a wheel of Parmesan can weigh around 80 pounds, while a wheel of cheddar might range from 50 to 60 pounds. The size and shape of these units are not only practical for storage and aging but also reflect the craftsmanship and heritage of cheese-making. Understanding these large units is essential for both consumers and industry professionals, as it impacts pricing, handling, and culinary applications.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Wheel: Large, round cheese form, aged for flavor, common in hard varieties like Parmesan

- Block: Rectangular shape, often used for slicing, typical in cheddar or Swiss cheese

- Loaf: Semi-circular or cylindrical, seen in cheeses like Brie or Camembert

- Head: Traditional term for large, round cheeses, especially in historical contexts

- Truckle: Small to medium wheel, often used for artisanal or specialty cheeses

Wheel: Large, round cheese form, aged for flavor, common in hard varieties like Parmesan

A wheel of cheese is a masterpiece of patience and precision, a testament to the art of aging. This large, round form is not just a shape but a vessel for transformation, where milk becomes a complex, hard cheese like Parmesan. The wheel’s size—often weighing between 60 to 100 pounds—is no accident; it’s a balance of surface area and volume that allows for slow, even maturation. Over months or even years, the cheese develops its signature crystalline texture and nutty depth, a process that smaller forms cannot replicate.

To appreciate a wheel of cheese, consider its anatomy. The rind, often natural or waxed, acts as a protective barrier, regulating moisture loss and shielding the interior from contaminants. Beneath it, the paste (the interior of the cheese) evolves from supple to firm, its flavor intensifying with time. For example, a young Parmesan wheel at 12 months is milder and more crumbly, while one aged 24 months or more becomes granular, sharp, and ideal for grating. This progression is why wheels are prized in hard cheeses—they allow for a spectrum of flavors within a single form.

If you’re handling a wheel of cheese, whether in a kitchen or a shop, there are practical steps to ensure its integrity. First, store it in a cool, humid environment (ideally 50–55°F with 80–85% humidity) to mimic the aging cave conditions. When cutting into it, use a cheese wire or a thin, sharp knife to preserve the structure—a rough break can expose too much surface area, accelerating drying. For longevity, wrap unused portions in wax paper and foil, not plastic, to allow the cheese to breathe.

The wheel’s dominance in hard cheeses isn’t just tradition—it’s science. Its circular shape minimizes exposure to air while maximizing the amount of cheese that can age uniformly. Compare this to smaller blocks or wedges, which lose moisture faster and develop uneven textures. For instance, a 100-pound wheel of Parmesan has a surface-to-volume ratio that allows it to age gracefully, whereas a 5-pound wedge would dry out before reaching the same complexity. This efficiency is why wheels are the preferred format for cheesemakers aiming for premium, aged varieties.

Finally, the wheel’s cultural significance cannot be overlooked. From the Alpine dairies of Switzerland to the hills of Italy, large rounds of cheese have been a symbol of craftsmanship and community for centuries. Sharing a wedge from a wheel is more than a meal—it’s a connection to history and the labor of cheesemakers. So, the next time you grate Parmesan over pasta or savor a slice of aged Gouda, remember: you’re not just enjoying cheese, you’re partaking in a legacy shaped, quite literally, by the wheel.

Should You Refrigerate Ham and Cheese Croissants? Storage Tips Revealed

You may want to see also

Block: Rectangular shape, often used for slicing, typical in cheddar or Swiss cheese

A block of cheese is a staple in many kitchens, prized for its versatility and ease of use. Its rectangular shape is no accident—it’s designed for efficiency, allowing for clean, uniform slices that suit everything from sandwiches to cheese boards. This form factor is particularly common in harder varieties like cheddar and Swiss, where the density of the cheese supports slicing without crumbling. For home cooks, a block offers better value than pre-shredded options, as it lasts longer when stored properly. Wrap it tightly in wax paper or aluminum foil, then place it in an airtight container to maintain freshness and prevent absorption of other flavors in the fridge.

When selecting a block, consider the intended use. A 1-pound block is a practical size for most households, providing enough cheese for several meals without overwhelming storage space. For larger gatherings or commercial kitchens, 5-pound blocks are available, though they require more careful handling to avoid waste. The uniformity of a block also makes it ideal for grating or cubing, tasks that are more cumbersome with irregularly shaped cheeses. If you’re slicing for a charcuterie board, aim for pieces about 1/4-inch thick—thin enough to melt in the mouth but substantial enough to showcase texture.

The rectangular shape of a block isn’t just functional; it’s also a nod to tradition. Cheddar and Swiss cheeses have been produced in block form for centuries, reflecting their origins in regions where practicality and preservation were paramount. This shape minimizes exposed surface area, slowing moisture loss and mold growth. For those aging cheese at home, blocks are easier to monitor and flip than wheels or wedges. Keep aging blocks in a cool, humid environment, such as a wine fridge set to 50–55°F, and inspect them weekly for proper rind development.

While blocks are celebrated for their utility, they’re not without quirks. Slicing through a cold block can be challenging, often resulting in jagged edges or uneven thickness. To achieve professional-looking slices, let the cheese sit at room temperature for 15–20 minutes before cutting. Use a sharp, non-serrated knife for clean edges, and apply gentle, even pressure. For softer varieties like young cheddar, a wire cheese slicer can produce wafer-thin pieces ideal for layering in dishes like quiches or grilled cheese sandwiches.

Finally, the block’s simplicity belies its role as a canvas for creativity. Beyond basic slicing, it can be carved into decorative shapes, melted into sauces, or cubed for salads and skewers. For a crowd-pleasing appetizer, try cutting a block of Swiss into 1-inch cubes, wrapping each in a slice of prosciutto, and baking until golden. The block’s consistent texture ensures even cooking, while its flavor profile complements a wide range of ingredients. Whether you’re a casual cook or a culinary enthusiast, mastering the block opens up a world of cheesy possibilities.

Teacher's Unexpected Reaction to Ogars' Cheese Report: A Surprising Twist

You may want to see also

Loaf: Semi-circular or cylindrical, seen in cheeses like Brie or Camembert

A loaf, in the context of cheese, is a distinctive shape that immediately brings to mind the creamy, indulgent textures of Brie and Camembert. These semi-circular or cylindrical forms are not just aesthetically pleasing but also functional, allowing the cheese to mature evenly and develop its signature rind. The loaf shape is particularly suited to soft, surface-ripened cheeses, where the exterior mold plays a crucial role in flavor development. For instance, Brie’s white, velvety rind contrasts beautifully with its gooey interior, a result of the loaf’s design enabling proper airflow and moisture retention during aging.

When selecting a loaf-shaped cheese, consider the size and weight, as these factors influence both portioning and storage. A standard wheel of Brie typically weighs between 2 and 3 pounds, making it ideal for small gatherings or as a centerpiece on a cheese board. For larger events, opt for a double or triple crème variety, which often comes in slightly larger loaves. To maintain freshness, store the cheese in its original wrapping or wax paper, and place it in the refrigerator’s warmest section, usually the bottom shelf. Allow the cheese to come to room temperature before serving to enhance its flavor and texture.

The loaf shape also lends itself to creative presentation. For a rustic touch, serve the cheese on a wooden board surrounded by fresh fruit, nuts, and crusty bread. For a more elegant display, slice the loaf into wedges and arrange them on a marble platter with a drizzle of honey or a scattering of edible flowers. Pairing is key: Brie and Camembert pair beautifully with sparkling wines or light, fruity reds. For a non-alcoholic option, try a crisp apple cider or a rich, dark stout to complement the cheese’s earthy notes.

From a culinary perspective, the loaf’s shape makes it versatile in recipes. Use slices of Brie as a melting topping for burgers or sandwiches, or bake the entire wheel in puff pastry for a decadent appetizer. Camembert, with its slightly tangier profile, works well in sauces or as a stuffing for mushrooms. When cooking with loaf cheeses, avoid overheating, as this can cause the interior to become oily or separate. Instead, aim for a gentle warmth that allows the cheese to soften and meld with other ingredients.

In conclusion, the loaf is more than just a shape—it’s a testament to the artistry of cheesemaking. Whether enjoyed on its own or incorporated into dishes, this form ensures a sensory experience that balances texture, flavor, and visual appeal. By understanding its characteristics and handling it with care, you can elevate any culinary moment, proving that sometimes, the best things in life are shaped like a loaf.

Perfect Quiche Measurements: How Many Ounces of Manchego Cheese to Use?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Head: Traditional term for large, round cheeses, especially in historical contexts

In the annals of cheese history, the term "head" emerges as a venerable designation for large, round cheeses, particularly those crafted in bygone eras. This nomenclature harkens back to a time when cheese-making was as much an art as it was a science, and the size and shape of the final product were dictated by tradition and practicality. A head of cheese, often weighing between 50 to 100 pounds, was a testament to the cheesemaker’s skill and the abundance of milk from local herds. Such cheeses were not merely food but also symbols of prosperity and community, often shared during festivals or traded in markets.

Consider the process of crafting a head of cheese: it begins with curdling large quantities of milk, typically from cows, sheep, or goats, followed by pressing the curds into a round mold. The mold’s size and shape were critical, as they determined the cheese’s final form and its ability to age properly. For instance, a traditional Swiss Emmental or a Dutch Gouda often started as a head, its large size allowing for slow, even maturation. This method ensured that the cheese developed complex flavors and a firm yet yielding texture, qualities that were highly prized in historical contexts.

From a practical standpoint, the term "head" also reflects the logistical considerations of cheese production and storage. Large cheeses were easier to handle and transport in an era before modern packaging and refrigeration. A single head could sustain a family or village for weeks, making it a valuable commodity. Additionally, the round shape facilitated stacking and aging in cellars or caves, where controlled humidity and temperature were crucial for ripening. This efficiency made the head a preferred unit for both artisans and merchants.

To appreciate the legacy of the head, one need only look at its enduring presence in culinary traditions. In medieval Europe, a head of cheese was often the centerpiece of feasts, sliced and shared among guests as a sign of hospitality. Today, while smaller cheeses dominate the market, the term still resonates in artisanal cheese-making circles, where preserving historical techniques is paramount. For enthusiasts, seeking out a head of cheese offers a taste of history—a connection to the craftsmanship and communal values of earlier times.

In conclusion, the term "head" encapsulates more than just a unit of measurement; it embodies a rich cultural and practical heritage. Whether you’re a historian, a cheesemaker, or simply a lover of fine cheeses, understanding this traditional term provides a deeper appreciation for the artistry and ingenuity behind one of humanity’s oldest foods. Next time you encounter a large, round cheese, remember the centuries of tradition it represents—and savor it accordingly.

Truckle: Small to medium wheel, often used for artisanal or specialty cheeses

A truckle of cheese, typically weighing between 2 to 4 pounds (0.9 to 1.8 kilograms), is a small to medium-sized wheel that has become synonymous with artisanal and specialty cheeses. This size is ideal for small-batch production, allowing cheesemakers to experiment with unique flavors, textures, and aging processes. Unlike larger wheels, truckles are often handcrafted, ensuring attention to detail and a distinct character that appeals to connoisseurs. Their compact size also makes them accessible for home use, as they are easier to store and consume before spoilage.

From a practical standpoint, truckles are perfect for those looking to explore a variety of cheeses without committing to a larger, more expensive wheel. For instance, a 3-pound truckle of aged cheddar can last a household of four up to two weeks when stored properly in a cheese vault or wrapped in wax paper. To maximize freshness, rotate the truckle weekly and trim any mold with a clean knife, ensuring it doesn’t penetrate more than a quarter-inch into the cheese. This size also lends itself well to gifting, as it’s substantial enough to impress yet manageable for the recipient.

Artisanal cheesemakers favor truckles because they age more predictably than larger wheels. A 2.5-pound truckle of Brie, for example, reaches its optimal creamy texture in just 4 to 6 weeks, compared to the 6 to 8 weeks required for a 5-pound wheel. This quicker turnaround allows producers to test new recipes and respond to market trends more efficiently. Additionally, truckles are often sold at a premium, reflecting the craftsmanship and quality that goes into their production, making them a profitable choice for small-scale operations.

When selecting a truckle, consider the cheese’s intended use. A semi-soft truckle like Taleggio is ideal for melting in dishes like grilled cheese or risotto, while a harder truckle like Pecorino pairs well with crackers and wine. For aging enthusiasts, a young truckle of Gouda can be stored for up to 6 months to develop a crystalline, nutty flavor. Always store truckles in the refrigerator’s vegetable drawer, where humidity is higher, and avoid plastic wrap, which can trap moisture and encourage spoilage.

In comparison to larger cheese formats, truckles offer a balance of convenience and quality. While a 20-pound wheel of Parmesan is cost-effective for restaurants, a truckle provides the same artisanal experience on a smaller scale. This makes truckles particularly appealing to home cooks, cheese boards enthusiasts, and those seeking to support local cheesemakers. Their size also encourages experimentation, allowing consumers to sample rare or seasonal varieties without overwhelming their palate or pantry. Whether you’re a novice or a seasoned cheese lover, truckles are a versatile and rewarding choice.

Frequently asked questions

A large unit of cheese is often called a wheel or block, depending on the shape and type of cheese.

Yes, in some regions, large cheese units are called truckles (in the UK) or forms (in Italy), especially for traditional varieties like Parmesan.

A large unit of cheese, such as a wheel of Cheddar or Gouda, can weigh anywhere from 20 to 100 pounds (9 to 45 kg), depending on the type and production method.