Rind cheese refers to any cheese that has a protective outer layer, known as the rind, which forms naturally or is added during the cheese-making process. This rind can vary in texture, from soft and bloomy to hard and waxy, and it plays a crucial role in shaping the cheese's flavor, texture, and shelf life. While some rinds are edible and contribute to the overall taste experience, others are meant to be removed before consumption. Understanding the characteristics and purpose of the rind enhances appreciation for the complexity and diversity of cheeses, making it an essential aspect of cheese connoisseurship.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | A cheese with a protective outer layer (rind) formed during aging. |

| Purpose of Rind | Protects the cheese from spoilage, influences flavor, texture, and appearance. |

| Types of Rind | Natural, bloomy, washed, smeared, hard, artificial. |

| Natural Rind | Formed by bacteria and molds naturally present on the cheese surface. |

| Bloomy Rind | Thin, velvety, white rind (e.g., Brie, Camembert) from Penicillium candidum. |

| Washed Rind | Soft, sticky, orange/red rind (e.g., Munster, Époisses) from brine washing. |

| Smeared Rind | Similar to washed rind but with a thicker, tackier surface (e.g., Limburger). |

| Hard Rind | Thick, hard outer layer (e.g., Parmesan, Gruyère) from long aging. |

| Artificial Rind | Coated with wax, cloth, or other materials for protection (e.g., Cheddar). |

| Flavor Contribution | Adds earthy, nutty, pungent, or savory flavors depending on the rind type. |

| Edibility | Some rinds are edible (e.g., bloomy, washed), while others are not (e.g., hard). |

| Aging Impact | Rind development and characteristics intensify with aging time. |

| Examples | Brie, Camembert, Époisses, Parmesan, Limburger, Munster. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Types of Rind Cheese: Hard, soft, natural, washed, bloomy, each type has unique characteristics and flavors

- Rind Formation Process: Bacteria, mold, aging, and environment contribute to rind development on cheese surfaces

- Edibility of Rinds: Some rinds are edible, adding texture and flavor, while others are meant to be removed

- Flavor Contribution: Rinds enhance cheese flavor through microbial activity, imparting earthy, nutty, or pungent notes

- Cheese Aging and Rind: Rinds protect cheese during aging, influencing moisture loss, texture, and flavor development

Types of Rind Cheese: Hard, soft, natural, washed, bloomy, each type has unique characteristics and flavors

Rind cheeses are a diverse category, each type distinguished by its texture, flavor, and the method used to develop its exterior. Among the most notable are hard, soft, natural, washed, and bloomy rind cheeses, each offering a unique sensory experience. Understanding these types not only enhances appreciation but also guides pairing and serving choices.

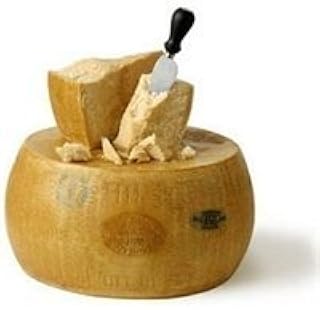

Hard Rind Cheeses: The Aged Masters

Hard rind cheeses, such as Parmigiano-Reggiano and Pecorino, are aged for months or even years, developing a dense, granular texture and a sharp, nutty flavor. Their rinds are typically natural, formed during the aging process, and are often inedible but serve to protect the cheese. To enjoy, grate over pasta or shave thinly onto salads. A practical tip: store hard cheeses in the refrigerator wrapped in wax paper to maintain moisture without promoting mold.

Soft Rind Cheeses: Creamy Indulgence

Soft rind cheeses, like Brie and Camembert, are characterized by their bloomy, edible rinds and velvety interiors. These cheeses age for a shorter period, usually 4–8 weeks, resulting in mild, earthy flavors. The rind is a key player, contributing complexity and a slight tang. Serve at room temperature to fully appreciate their texture. Pair with a crisp white wine or fresh fruit for a balanced experience.

Natural Rind Cheeses: Simplicity at Its Best

Natural rind cheeses, such as Tomme or young Gouda, develop their rinds through exposure to air during aging. These rinds are often thin and edible, adding a subtle earthy or grassy note to the cheese. The interior ranges from semi-soft to firm, depending on age. For optimal flavor, let the cheese breathe at room temperature for 30 minutes before serving. These cheeses pair well with rustic bread and light salads.

Washed Rind Cheeses: Bold and Pungent

Washed rind cheeses, like Époisses and Taleggio, are brushed with brine, wine, or beer during aging, fostering bacteria that create a sticky, orange rind and a robust aroma. Beneath the surface lies a creamy, rich interior with flavors ranging from savory to slightly meaty. These cheeses are not for the faint of heart but are perfect for those seeking intensity. Serve with dark bread or cured meats to complement their boldness.

Bloomy Rind Cheeses: The Delicate Balance

Bloomy rind cheeses, such as Saint André or Coulommiers, are coated in a white mold (Penicillium camemberti) that creates a soft, edible rind and a luscious interior. Aging typically lasts 4–6 weeks, resulting in a mild, buttery flavor with hints of mushroom. These cheeses are best enjoyed at room temperature, spread on crackers or paired with honey for a sweet contrast. A caution: avoid overheating, as it can cause the cheese to become greasy.

Each type of rind cheese offers a distinct journey, from the aged complexity of hard rinds to the creamy decadence of bloomy varieties. By understanding their characteristics, you can elevate your cheese board and culinary creations, ensuring every bite is a discovery.

Elegant Smoked Salmon and Cheese Platter Display Ideas & Tips

You may want to see also

Rind Formation Process: Bacteria, mold, aging, and environment contribute to rind development on cheese surfaces

The rind of a cheese is not merely a protective barrier but a complex ecosystem where bacteria, mold, aging, and environmental factors collaborate to create texture, flavor, and character. This natural process transforms the cheese’s surface into a dynamic layer that ranges from soft and bloomy to hard and crystalline. Understanding the rind formation process reveals the intricate science behind one of cheese’s most distinctive features.

Bacteria and Mold: The Microbial Architects

Rind development begins with microorganisms introduced intentionally or naturally during cheesemaking. For example, Brie and Camembert rinds are cultivated with *Penicillium camemberti*, a mold that creates a velvety white exterior. Similarly, washed-rind cheeses like Époisses rely on *Brevibacterium linens*, a bacterium responsible for their orange-red hue and pungent aroma. These microbes break down proteins and fats on the cheese surface, producing enzymes that contribute to flavor and texture. The type and concentration of bacteria or mold determine whether the rind becomes bloomy, washed, or natural. For instance, a dosage of 10^6 CFU/mL of *Penicillium* spores is commonly used to inoculate bloomy rinds, ensuring even coverage and consistent growth.

Aging: Time as a Transformative Force

Aging is critical to rind formation, as it allows microbial activity to mature and deepen the cheese’s characteristics. During this phase, moisture evaporates, and the rind thickens or hardens, depending on the cheese variety. For instance, a young Gouda has a thin, pliable rind, but after 12–24 months of aging, it becomes a hard, wax-like barrier. In contrast, a washed-rind cheese like Taleggio develops its signature sticky texture and robust flavor after 6–10 weeks of aging, during which it is regularly brushed with brine to encourage bacterial growth. The longer the aging period, the more pronounced the rind’s attributes become, though over-aging can lead to excessive dryness or off-flavors.

Environment: The Unseen Influencer

The environment in which cheese ages plays a pivotal role in rind development. Humidity, temperature, and airflow dictate how microbes thrive and how moisture is retained or lost. For example, bloomy-rind cheeses require high humidity (around 90–95%) to support mold growth, while hard cheeses like Parmigiano-Reggiano benefit from drier conditions (50–60%) to prevent mold and encourage crystallization. Temperature control is equally crucial; washed-rind cheeses age best at 10–13°C (50–55°F), fostering bacterial activity without spoilage. Practical tips for home aging include using a wine fridge set to 12°C (54°F) and placing a bowl of water inside to maintain humidity.

Practical Takeaways for Rind Appreciation

Understanding the rind formation process enhances both cheesemaking and consumption. For makers, controlling microbial inoculation, aging time, and environmental conditions is key to achieving desired outcomes. For consumers, knowing the rind’s role allows for informed decisions—whether to eat it (as with bloomy or washed rinds) or remove it (as with some waxed cheeses). Pairing cheese with beverages or dishes can also highlight the rind’s unique flavors; for instance, a bold washed-rind cheese pairs well with a robust red wine, while a delicate bloomy rind complements sparkling wine. By appreciating the science behind rind formation, one gains a deeper respect for the artistry of cheese.

Can Dogs Eat Jalapeño Poppers Cheese Curls? Safety Guide

You may want to see also

Edibility of Rinds: Some rinds are edible, adding texture and flavor, while others are meant to be removed

Cheese rinds are not one-size-fits-all. Their edibility varies widely, influenced by factors like the cheese-making process, aging time, and type of bacteria or mold used. For instance, the bloomy rind of a Camembert is not only edible but prized for its creamy texture and earthy flavor, while the thick, wax-like rind of a Gouda is typically removed before consumption. Understanding this distinction can elevate your cheese experience from mundane to masterful.

When approaching a cheese rind, consider its appearance and texture as your first clue. Soft, bloomy rinds, such as those on Brie or Saint André, are almost always edible and contribute to the cheese’s overall character. In contrast, hard, natural rinds like those on Parmigiano-Reggiano or aged Cheddar are often too tough or flavorless to enjoy. A notable exception is the rind of Alpine cheeses like Comte, which, while firm, can be pleasantly nutty and worth nibbling. Always inspect the rind for any signs of spoilage, such as off-colors or odors, before deciding whether to eat it.

For those new to cheese exploration, start with varieties where the rind is intentionally part of the experience. A young, washed-rind cheese like Taleggio has a thin, edible rind that adds a pungent, savory kick. Pair it with crusty bread or fruit to balance its intensity. Conversely, when serving semi-hard cheeses like Manchego, encourage guests to peel away the inedible rind to focus on the cheese’s interior. This simple act of discernment demonstrates respect for the cheese’s craftsmanship and ensures every bite is enjoyable.

Finally, don’t shy away from experimenting with rinds in cooking. Edible rinds can be melted into sauces, grated over dishes, or even baked for a crispy topping. For example, the rind of a high-quality Gruyère can add depth to soups or casseroles. However, always avoid cooking with rinds that are waxed, heavily treated, or show signs of mold beyond the intended variety. By treating cheese rinds as an ingredient in their own right, you unlock a world of culinary possibilities while minimizing waste.

Cheesy Strategies to Escape Silver Rank in Competitive Gaming

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Flavor Contribution: Rinds enhance cheese flavor through microbial activity, imparting earthy, nutty, or pungent notes

Cheese rinds are not merely protective barriers; they are dynamic ecosystems teeming with microorganisms that significantly influence flavor. These microbial communities—bacteria, yeasts, and molds—metabolize compounds within the cheese, breaking down proteins and fats into volatile compounds that contribute to its aroma and taste. For instance, *Penicillium camemberti* on Camembert rinds produces earthy and mushroom-like notes, while *Brevibacterium linens* on washed-rind cheeses like Époisses imparts pungent, barnyard aromas. This microbial activity is a cornerstone of rind-ripened cheeses, transforming them from bland curds into complex, flavorful masterpieces.

To understand the flavor contribution of rinds, consider the aging process. As cheese matures, the rind acts as a living interface, regulating moisture exchange and fostering microbial growth. In semi-soft cheeses like Brie, the rind’s white mold blooms, creating an ammonia-like compound that mellows into nutty, buttery flavors over 4–6 weeks. Harder cheeses, such as aged Gouda, develop crystalline tyrosine through microbial activity, adding a crunchy texture and caramelized, toffee-like notes. The longer the aging, the more pronounced these flavors become, with some cheeses aged up to 2 years for maximum depth.

Practical tip: When selecting rind-ripened cheeses, inspect the rind for uniformity and color, as these indicate proper microbial development. For washed-rind cheeses, a sticky, orange-hued rind signals active *Brevibacterium* cultures, promising robust flavors. Conversely, a dry, cracked rind on a soft cheese may indicate over-aging or improper storage. Always store rind cheeses in wax paper or cheese wrap to allow breathability, and serve them at room temperature to fully appreciate the rind’s flavor contribution.

Comparatively, rindless cheeses like fresh mozzarella or cream cheese lack the microbial complexity of their rinded counterparts. While they offer clean, milky flavors, they miss the earthy, nutty, or pungent notes that rinds provide. This contrast highlights the rind’s role as a flavor enhancer, not just a structural element. For those hesitant to consume rinds, note that many are edible and safe, though thicker, waxier rinds (like those on Cheddar) are often removed.

In conclusion, the rind is not merely a byproduct of cheese production but a vital component that elevates flavor through microbial activity. From the earthy undertones of a bloomy rind to the pungent kick of a washed rind, these microbial ecosystems create a sensory experience that defines rind-ripened cheeses. By understanding and appreciating this process, cheese enthusiasts can better select, store, and savor these artisanal creations.

Is Black Bomber Cheese Vegetarian? Uncovering the Truth Behind the Label

You may want to see also

Cheese Aging and Rind: Rinds protect cheese during aging, influencing moisture loss, texture, and flavor development

Cheese rinds are not merely outer layers but essential guardians of the aging process, dictating how a cheese evolves in texture, flavor, and moisture content. Consider the difference between a supple Brie with its bloomy white rind and a hard Parmigiano-Reggiano encased in a natural, waxy shell. The rind’s composition—whether it’s smeared with bacteria, coated in wax, or left to develop naturally—determines how much moisture escapes and how microbial cultures interact with the cheese. For instance, a washed-rind cheese like Époisses loses moisture slowly, allowing its interior to remain creamy, while a hard cheese’s rind minimizes moisture loss entirely, resulting in a dry, crumbly texture. Understanding this relationship reveals why rinds are not just protective barriers but active participants in cheese maturation.

To appreciate the rind’s role, observe how it manages moisture during aging. In a humid aging environment, a natural rind on a cheese like Cheddar acts as a semi-permeable membrane, allowing controlled moisture evaporation. This gradual drying concentrates flavors and firms the texture, ideal for cheeses meant to age over months or years. Conversely, a wax-coated rind on a Gouda blocks moisture loss entirely, preserving a pliable interior. Home cheesemakers can experiment with this by aging identical cheeses with and without wax coatings, noting how the latter develops a drier, more crystalline texture over 6–12 months. The key takeaway: rinds are not one-size-fits-all; their design must align with the desired moisture content and aging timeline.

Flavor development in aged cheeses is deeply intertwined with rind composition and microbial activity. Take a blue cheese like Roquefort, where the rind allows Penicillium spores to penetrate the interior, creating veins of sharp, pungent flavor. In contrast, a washed-rind cheese like Taleggio is regularly brushed with brine, encouraging bacteria like Brevibacterium linens to thrive on the surface, imparting earthy, meaty notes. Even non-edible rinds, like those on aged Alpine cheeses, contribute indirectly by fostering an environment where enzymes break down proteins and fats, enriching the flavor profile. For enthusiasts, pairing rind types with specific bacterial cultures—such as Geotrichum candidum for bloomy rinds—can elevate homemade cheeses from good to exceptional.

Practical considerations for aging cheese with rinds include humidity control and rind maintenance. Ideal aging conditions range from 85–90% humidity for bloomy-rind cheeses to 70–75% for harder varieties. Regularly flipping cheeses prevents uneven moisture distribution, while brushing or wiping washed rinds every 2–3 weeks ensures bacterial growth remains balanced. For natural rinds, avoid excessive handling to prevent mold contamination. A pro tip: use a hygrometer to monitor aging conditions and adjust ventilation as needed. By mastering these techniques, even novice cheesemakers can harness the rind’s protective and transformative power, turning humble curds into complex, aged masterpieces.

Is Cheese Fattening at Night? Unraveling the Late-Night Snack Myth

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A rind cheese is a type of cheese that has a protective outer layer, called the rind, which forms naturally or is added during the cheese-making process. The rind can vary in texture, thickness, and flavor, depending on the cheese variety.

The rind of a cheese can form in several ways: through natural mold growth (e.g., Brie), bacterial action (e.g., washed-rind cheeses), waxing or coating (e.g., Cheddar), or pressing and aging (e.g., Parmesan). Each method contributes to the cheese's unique flavor and texture.

Whether the rind is edible depends on the type of cheese. Soft, bloomy rinds (like Brie) are typically edible and add flavor. Hard, waxed rinds (like Gouda) are usually not eaten. Washed or smear rinds (like Epoisses) can be edible but are often strong in flavor. Always check the specific cheese for guidance.