In the process of making cheese, milk is coagulated to separate it into curds and whey, a crucial step that transforms liquid milk into a solid cheese base. This coagulation is typically achieved by adding specific enzymes or acids, with the most common being rennet, a complex of enzymes derived from the stomachs of ruminant animals. Rennet contains chymosin, which acts on the milk protein casein, causing it to form a gel-like structure. Alternatively, microbial transglutaminase or acid-producing bacteria can be used, especially in vegetarian or certain traditional cheese-making methods. These coagulants work by destabilizing the milk’s colloidal structure, allowing the curds to form and the whey to separate, setting the stage for further cheese production.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Type of Coagulant | Rennet (animal-derived), Microbial Enzymes, Acid (e.g., vinegar, lemon juice), Vegetable-based coagulants (e.g., fig tree bark, nettles) |

| Primary Enzyme | Chymosin (in rennet), Mucor miehei (microbial), Pepsin (animal-derived alternative) |

| Function | Coagulates milk by curdling casein proteins, separates curds from whey |

| Optimal pH Range | 6.0–6.6 (rennet), 4.5–5.5 (acid coagulation) |

| Optimal Temperature | 30–35°C (86–95°F) for rennet, varies for microbial enzymes |

| Source | Animal stomach lining (rennet), microbial cultures, plants, or synthetic production |

| Strength | Measured in IMCU (International Milk Clotting Units) for rennet |

| Effect on Flavor | Neutral to mild (rennet), tangy (acid), varies with vegetable coagulants |

| Common Use | Hard and semi-hard cheeses (rennet), fresh cheeses (acid), traditional/vegetarian cheeses (vegetable) |

| Vegetarian/Vegan Suitability | No (animal rennet), Yes (microbial, acid, vegetable coagulants) |

| Allergen Concerns | Potential for milk allergens; vegetable coagulants may cause reactions in sensitive individuals |

| Shelf Stability | Varies; liquid rennet requires refrigeration, powdered forms are stable |

| Cost | Rennet is moderate to high, acid is low-cost, microbial enzymes vary |

| Availability | Widely available (rennet, acid), specialized sources (vegetable coagulants) |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Rennet Enzymes: Animal-derived chymosin and pepsin are traditional coagulants for cheese making

- Microbial Coagulants: Vegetarian alternatives include Mucor miehei and Rhizomucor miehei enzymes

- Acid Coagulation: Vinegar, lemon juice, or lactic acid can curdle milk for fresh cheeses

- Plant-Based Coagulants: Extracts from fig trees, nettles, or thistles are used in some regions

- Synthetic Enzymes: Lab-produced chymosin offers consistent results for industrial cheese production

Rennet Enzymes: Animal-derived chymosin and pepsin are traditional coagulants for cheese making

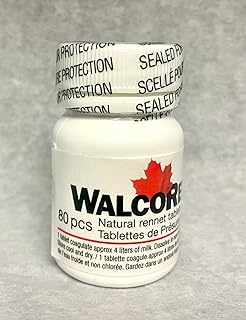

Rennet enzymes, specifically animal-derived chymosin and pepsin, have been the cornerstone of cheese making for centuries. These enzymes, extracted primarily from the stomach lining of ruminant animals like calves, lambs, and goats, play a pivotal role in coagulating milk. Chymosin, the more potent of the two, selectively cleaves the milk protein κ-casein, causing the milk to curdle into a firm, elastic curd ideal for cheese production. Pepsin, while less specific, works in tandem to ensure complete coagulation. This traditional method not only preserves the integrity of the cheese’s texture and flavor but also aligns with historical practices that have stood the test of time.

The application of rennet enzymes in cheese making is both an art and a science. Typically, 0.02% to 0.05% of liquid rennet (diluted in water) is added to milk at a temperature of 30–35°C (86–95°F), depending on the cheese variety. For harder cheeses like Cheddar, a higher dosage of chymosin is used to achieve a firmer curd, while softer cheeses like Brie may require a lower dosage. It’s crucial to stir the rennet gently into the milk for 30–60 seconds to ensure even distribution, then allow the mixture to rest undisturbed for 30–60 minutes until a clean break is achieved. Overuse of rennet can lead to a bitter taste, while underuse may result in a weak, crumbly curd.

Despite their effectiveness, animal-derived rennet enzymes are not without controversy. Ethical concerns surrounding the sourcing of animal byproducts have spurred the development of microbial and plant-based alternatives. However, for purists and traditionalists, animal rennet remains unmatched in its ability to produce cheeses with authentic texture and flavor profiles. For home cheese makers, sourcing high-quality rennet tablets or liquid from reputable suppliers is essential. Always follow the manufacturer’s instructions for dilution and storage, as rennet loses potency when exposed to heat or direct sunlight.

In comparison to modern coagulants, animal-derived rennet enzymes offer a unique advantage: their specificity in targeting κ-casein ensures a consistent and predictable curdling process. Microbial rennets, while vegetarian-friendly, often lack the precision of chymosin, leading to variations in curd formation. For those committed to traditional cheese making, understanding the nuances of rennet enzymes—their dosage, temperature sensitivity, and interaction with milk proteins—is key to mastering the craft. Whether you’re crafting a wheel of Parmesan or a batch of fresh mozzarella, the choice of rennet can make or break the final product.

Tillamook Cheese Factory: Top Activities and Must-Try Experiences for Visitors

You may want to see also

Microbial Coagulants: Vegetarian alternatives include Mucor miehei and Rhizomucor miehei enzymes

Traditional cheesemaking relies heavily on rennet, a complex of enzymes derived from the stomach lining of ruminant animals. However, the demand for vegetarian and vegan alternatives has spurred innovation in microbial coagulants. Among these, enzymes from *Mucor miehei* and *Rhizomucor miehei* have emerged as effective substitutes, offering a plant-based solution without compromising on texture or flavor. These microbial enzymes, known as mucorpeptidase or fungal rennet, act on milk proteins in a manner similar to animal rennet, catalyzing the coagulation process essential for cheese formation.

The application of *Mucor miehei* and *Rhizomucor miehei* enzymes in cheesemaking requires precision. Typically, dosages range from 0.05% to 0.1% of the milk volume, depending on the desired curd firmness and the specific enzyme concentration. For instance, a 100-liter batch of milk might require 50–100 ml of a 10,000 IMCU/ml enzyme solution. It’s crucial to monitor pH levels during coagulation, as these enzymes perform optimally in the range of 6.0 to 6.6. Overuse can lead to bitter flavors or overly firm curds, while underuse may result in weak, rubbery textures.

One of the standout advantages of microbial coagulants is their consistency. Unlike animal rennet, which can vary in potency due to biological differences, *Mucor miehei* and *Rhizomucor miehei* enzymes provide reliable results batch after batch. This predictability is particularly valuable for artisanal and industrial cheesemakers alike, ensuring product uniformity. Additionally, these enzymes are heat-stable, allowing them to withstand pasteurization temperatures, a feature that simplifies processing for certain cheese varieties.

Despite their benefits, microbial coagulants are not without limitations. Some cheesemakers report subtle differences in flavor profiles when compared to traditional rennet, particularly in aged cheeses. However, for fresh and semi-soft cheeses, such as mozzarella or ricotta, the distinction is often negligible. For best results, experiment with enzyme dosages and coagulation times to tailor the process to specific cheese types. Pairing microbial coagulants with vegetarian-friendly cultures can further enhance the authenticity of the final product.

Incorporating *Mucor miehei* and *Rhizomucor miehei* enzymes into cheesemaking not only caters to dietary preferences but also aligns with sustainability goals. By reducing reliance on animal-derived products, cheesemakers can appeal to a broader market while minimizing environmental impact. As the demand for vegetarian cheeses continues to rise, mastering the use of these microbial coagulants will become an essential skill for modern cheesemakers. With careful attention to dosage and technique, these enzymes offer a versatile, effective, and ethical alternative in the art of cheese production.

Broccoli Cheese Quiche Fat Content: A Nutritional Breakdown

You may want to see also

Acid Coagulation: Vinegar, lemon juice, or lactic acid can curdle milk for fresh cheeses

Acid coagulation is a simple, accessible method for curdling milk to make fresh cheeses, relying on common household ingredients like vinegar, lemon juice, or lactic acid. Unlike rennet, which is animal-derived and works by enzymatic action, acids lower the milk’s pH, causing proteins to denature and form curds. This technique is ideal for beginners or those seeking quick, vegetarian-friendly cheese recipes, such as paneer, queso blanco, or chhena. The process is straightforward: heat milk to near-boiling, add the acid, and watch as the curds separate from the whey.

Steps for Acid Coagulation: Begin by heating 1 gallon (3.8 liters) of milk to 180–190°F (82–88°C), stirring occasionally to prevent scorching. Remove from heat and add 1/4 cup (60 ml) of distilled white vinegar or fresh lemon juice (strained to avoid pulp) for every gallon of milk. Stir gently for 10–15 seconds, then let the mixture rest for 5–10 minutes. The curds will form as a solid mass, while the whey becomes a translucent liquid. For a milder flavor, use 1–2 tablespoons of lactic acid diluted in water instead, adjusting based on the milk’s acidity.

Cautions and Tips: Over-stirring or excessive acid can lead to tough, rubbery curds, so precision is key. Distilled white vinegar or fresh lemon juice are preferred for their consistent acidity, while apple cider vinegar or other flavored acids may impart unwanted tastes. Always use full-fat milk for better curd formation, as low-fat or non-fat milk yields fewer curds. If the curds don’t form, reheat the mixture slightly and add a bit more acid, but avoid overdoing it.

Comparative Analysis: Acid-coagulated cheeses differ from rennet-based varieties in texture and flavor. They tend to be firmer and tangier, with a crumbly structure ideal for cooking or frying. Lactic acid, often used in cultured buttermilk, produces a smoother curd and milder taste compared to vinegar or lemon juice. This method is particularly useful for lactose-intolerant individuals, as the acid breaks down lactose during curdling.

Practical Takeaway: Acid coagulation is a versatile, beginner-friendly technique for making fresh cheeses in under an hour. With minimal equipment and common ingredients, it’s an excellent entry point into cheesemaking. Experiment with different acids and milk types to tailor the flavor and texture to your preferences. Whether for paneer in curries or queso blanco in salads, this method delivers quick, satisfying results without the complexity of traditional rennet-based processes.

Perfect Philly Cheese Steak: Mastering the Art of Slicing Meat

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Plant-Based Coagulants: Extracts from fig trees, nettles, or thistles are used in some regions

In the realm of artisanal cheese-making, plant-based coagulants offer a fascinating alternative to traditional animal-derived rennet. Extracts from fig trees, nettles, or thistles have been used for centuries in regions like the Mediterranean and parts of Europe, where local flora provides both flavor and function. These botanical coagulants not only cater to vegetarian and vegan diets but also impart unique characteristics to the cheese, such as earthy undertones or a firmer texture. Understanding their application requires precision, as the dosage and method can significantly impact the final product.

Steps to Using Plant-Based Coagulants:

- Harvesting and Preparation: For fig tree coagulants, collect the sap from the fig tree’s trunk or unripe figs, which contain ficin, a natural enzyme. Nettles and thistles require careful handling due to their spines; steep the leaves or flowers in hot water to extract the coagulating compounds.

- Dosage and Testing: Start with a small ratio, typically 1–2% of the milk volume, as plant enzymes can vary in potency. Test a sample of milk with the coagulant to gauge its strength before applying it to the entire batch.

- Application: Gently stir the coagulant into warmed milk (around 30–35°C) and allow it to rest for 30–60 minutes, depending on the desired curd formation. Over-stirring can weaken the curd, while insufficient mixing may result in uneven coagulation.

Cautions and Considerations:

Plant-based coagulants are less predictable than commercial rennet, as their enzyme activity depends on factors like plant age, season, and extraction method. For example, thistle coagulants work best with sheep’s milk, while fig extracts are more versatile but can overpower delicate cheeses. Additionally, these coagulants may not produce a hard curd suitable for aged cheeses, making them ideal for fresh or semi-soft varieties like ricotta or feta.

Practical Tips for Success:

- Store plant extracts in a cool, dry place to preserve their enzymatic activity.

- Experiment with blending coagulants (e.g., fig and nettle) to balance flavor and texture.

- For beginners, start with a simple cheese recipe like paneer or queso blanco to familiarize yourself with the process.

Takeaway:

Plant-based coagulants are not just a dietary alternative but a gateway to exploring regional cheese-making traditions. While they require more attention to detail, the reward lies in crafting cheeses with a distinct, natural character. By mastering these techniques, cheese makers can honor age-old practices while appealing to modern tastes and values.

Does Wax-Wrapped Cheese Require Refrigeration? Storage Tips Revealed

You may want to see also

Synthetic Enzymes: Lab-produced chymosin offers consistent results for industrial cheese production

Milk coagulation is a critical step in cheese production, traditionally achieved through the use of rennet, a complex of enzymes derived from the stomach lining of ruminant animals. However, the rise of synthetic enzymes, particularly lab-produced chymosin, has revolutionized industrial cheese-making by offering unparalleled consistency and efficiency. Chymosin, the primary enzyme responsible for curdling milk, is now genetically engineered through microbial fermentation, eliminating reliance on animal sources. This innovation addresses variability issues inherent in animal-derived rennet, ensuring precise control over the coagulation process. For instance, synthetic chymosin is typically added at a dosage of 0.02–0.05% (based on milk weight), a standardized measurement that guarantees optimal curd formation across large-scale production batches.

From an analytical perspective, the adoption of synthetic chymosin reflects a broader trend in food technology: the shift toward bioengineered solutions for enhanced reliability. Unlike animal-derived rennet, which can vary in potency due to factors like animal age or diet, lab-produced chymosin delivers a uniform enzymatic activity. This consistency is particularly crucial in industrial settings, where even minor deviations in coagulation can affect yield, texture, and flavor. Studies show that synthetic chymosin reduces curd formation time by up to 20%, streamlining production schedules and reducing costs. Moreover, its purity minimizes the risk of contaminants, a common concern with animal-based products.

For manufacturers considering the transition to synthetic enzymes, the process is straightforward but requires attention to detail. Begin by assessing your current coagulation method and desired cheese type, as chymosin’s effectiveness varies slightly depending on milk composition and pH. For hard cheeses like cheddar, a slightly higher dosage (0.04%) may be necessary to achieve a firmer curd. Soft cheeses, such as mozzarella, typically require a lower dosage (0.02%) to maintain elasticity. Always calibrate equipment to ensure accurate enzyme dispersion, as uneven distribution can lead to weak or uneven curds. Additionally, monitor milk temperature (ideally 30–35°C) during coagulation, as chymosin’s activity peaks within this range.

A comparative analysis highlights the advantages of synthetic chymosin over traditional rennet and other microbial coagulants. While microbial enzymes like mucorpepsin are vegetarian-friendly, they often produce bitter flavors in aged cheeses, a drawback absent in chymosin-curdled products. Similarly, animal rennet, though effective, faces ethical and sustainability concerns, as its production is tied to the meat industry. Synthetic chymosin, on the other hand, aligns with modern consumer demands for transparency and sustainability, as it reduces dependency on animal byproducts. Its cost-effectiveness further solidifies its position as the enzyme of choice for large-scale cheese producers.

In conclusion, synthetic chymosin exemplifies how biotechnology can address longstanding challenges in food production. By offering precision, scalability, and ethical benefits, it has become indispensable in industrial cheese-making. For producers, the key takeaway is clear: adopting lab-produced enzymes not only ensures consistent quality but also positions brands as innovators in a competitive market. As technology advances, synthetic enzymes like chymosin will likely play an even greater role in shaping the future of dairy processing.

Does Cheese in Gift Baskets Require Refrigeration? Essential Tips

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Rennet, a complex of enzymes, is commonly added to coagulate milk in cheese-making. It contains chymosin, which breaks down milk proteins, causing the milk to curdle.

Yes, vegetarian alternatives include microbial rennet (produced by bacteria or fungi) and plant-based coagulants like fig tree bark extract or thistle.

Yes, acids like vinegar or lemon juice can coagulate milk by lowering its pH, but this method is typically used for simpler cheeses like ricotta or paneer, not aged cheeses.

Calcium chloride is often added to milk, especially when using pasteurized milk, to restore calcium levels and improve the firmness of the curd during coagulation, enhancing the cheese's texture.