Aged cheese, often referred to as mature or ripened cheese, is a category of cheese that has been carefully stored and allowed to develop its flavors and textures over an extended period, ranging from several months to several years. This aging process, also known as ripening, involves controlled environments where factors like temperature, humidity, and airflow are meticulously managed to encourage the growth of beneficial bacteria and molds. As the cheese ages, its moisture content decreases, leading to a firmer texture, while enzymes break down proteins and fats, intensifying its flavor profile. The result is a complex, often nutty or sharp taste, with a denser, sometimes crumbly consistency that distinguishes aged cheeses from their younger counterparts. Popular examples include Parmesan, Cheddar, and Gouda, each showcasing unique characteristics shaped by their specific aging techniques and traditions.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Cheese that has been matured or stored for an extended period, typically ranging from several months to several years. |

| Texture | Harder, drier, and more crumbly compared to younger cheeses. Texture varies by type (e.g., Parmesan is granular, while Gouda becomes crystalline). |

| Flavor | More intense, complex, and sharper due to the breakdown of proteins and fats during aging. Notes can include nutty, caramelized, or umami flavors. |

| Aroma | Stronger and more pronounced, often with earthy, fruity, or pungent undertones. |

| Color | Deeper or darker hues, especially in the rind or interior, due to oxidation and microbial activity. |

| Moisture Content | Lower moisture content as water evaporates during aging, contributing to a firmer texture. |

| Fat Content | Fat concentration increases relative to moisture loss, enhancing richness. |

| Protein Breakdown | Proteins break down into amino acids, contributing to deeper flavors and umami qualities. |

| Microbial Activity | Beneficial bacteria and molds continue to develop, influencing flavor and texture. |

| Rind Development | Rinds become thicker, harder, or more pronounced, often with natural molds or wax coatings. |

| Examples | Parmesan, Cheddar, Gouda, Gruyère, Manchego, Pecorino, and Alpine-style cheeses. |

| Storage Requirements | Requires controlled environments (cool, humid, and well-ventilated) to prevent spoilage. |

| Shelf Life | Longer shelf life compared to fresh cheeses, but quality peaks at specific aging points. |

| Culinary Uses | Ideal for grating, shaving, or pairing with wines, crackers, and fruits due to bold flavors. |

| Nutritional Changes | Higher concentration of nutrients like calcium and protein per gram due to moisture loss. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Aging Process: Time, temperature, humidity transform fresh cheese into complex, flavorful aged varieties

- Types of Aged Cheese: Cheddar, Parmesan, Gouda, Gruyère, and more, each with unique characteristics

- Flavor Development: Aging intensifies taste, adding nuttiness, sharpness, or sweetness to the cheese

- Texture Changes: From soft to hard, crumbly to crystalline, texture evolves during aging

- Health Benefits: Higher protein, lower lactose, and probiotics make aged cheese a healthier option

Aging Process: Time, temperature, humidity transform fresh cheese into complex, flavorful aged varieties

Time is the alchemist of the cheese world, transforming humble curds into complex, nuanced masterpieces. The aging process, a delicate dance of time, temperature, and humidity, is the secret behind the depth of flavor and texture in aged cheeses. Consider this: a young cheddar, mild and supple, becomes a sharp, crumbly powerhouse after months or even years of maturation. This metamorphosis isn’t random; it’s a carefully controlled science.

The Role of Time: Aging duration dictates the intensity of flavor and texture. Soft cheeses like Camembert may age for just a few weeks, developing a creamy interior and bloomy rind. Harder cheeses, such as Parmigiano-Reggiano, require a minimum of 12 months, often extending to 36 months or more, to achieve their granular texture and umami-rich profile. Each additional day in the aging room deepens the cheese’s character, breaking down proteins and fats into amino acids and fatty acids that contribute to its complexity.

Temperature and Humidity: The Unseen Hands: Optimal aging requires precise environmental control. Temperatures typically range between 45°F and 55°F (7°C–13°C), with humidity levels between 80% and 90%. Too warm, and the cheese may spoil; too dry, and it will crack or lose moisture too quickly. For example, Alpine cheeses like Gruyère thrive in cooler, damper conditions, allowing their eyes (holes) to form and their nutty flavors to develop. In contrast, blue cheeses like Stilton benefit from slightly warmer temperatures to encourage mold growth, which creates their signature veins and pungency.

Practical Tips for Home Aging: While industrial aging rooms are highly controlled, home enthusiasts can experiment with smaller-scale setups. Use a wine fridge set to 50°F (10°C) and place a bowl of water inside to maintain humidity. Wrap the cheese in cheesecloth or wax paper, not plastic, to allow it to breathe. Turn the cheese weekly to ensure even moisture distribution. Start with forgiving varieties like cheddar or Gouda, aging them for 2–4 weeks to observe the transformation.

The Takeaway: Aging cheese is both an art and a science, where time, temperature, and humidity collaborate to create something greater than the sum of its parts. Whether you’re a cheesemaker or a connoisseur, understanding this process deepens your appreciation for the craft. Next time you savor a wedge of aged cheese, remember: every bite is the result of months or years of patient, deliberate transformation.

Sharp White Cheese Sticks: Carb Count and Nutritional Insights

You may want to see also

Types of Aged Cheese: Cheddar, Parmesan, Gouda, Gruyère, and more, each with unique characteristics

Aged cheese is a testament to the transformative power of time, where milk evolves into a complex, flavor-packed delicacy. Among the myriad varieties, Cheddar, Parmesan, Gouda, and Gruyère stand out, each with distinct characteristics shaped by their aging process. Cheddar, for instance, ranges from mild (aged 2–3 months) to extra sharp (aged 1–2 years), developing a deeper tang and crumbly texture as it matures. This progression highlights how aging intensifies flavor and alters texture, making Cheddar a versatile choice for everything from sandwiches to sauces.

Consider Parmesan, a hard Italian cheese aged a minimum of 12 months, often up to 36 months. Its extended aging results in a granular texture and a nutty, umami-rich profile that elevates dishes like pasta and risotto. Unlike younger cheeses, Parmesan’s aging process involves a natural rind formation and a slow moisture loss, concentrating its flavors. A practical tip: use a microplane grater to maximize its melt-in-your-mouth quality when garnishing dishes.

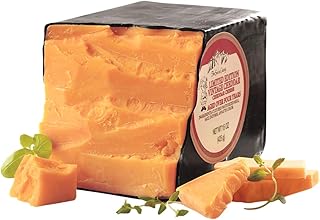

Gouda, a Dutch cheese, showcases how aging can shift a cheese’s identity. Young Gouda is mild and creamy, but as it ages (6–24 months), it becomes firmer, developing caramelized notes and a butterscotch hue. Aged Gouda’s crystalline texture and complex sweetness make it a standout on cheese boards or paired with bold wines. This transformation underscores the importance of aging duration in defining a cheese’s character.

Gruyère, a Swiss cheese aged 5–12 months, is celebrated for its meltability and nutty, slightly salty flavor. Its aging process fosters the development of small cracks and a smooth, hard texture, ideal for fondue or gratins. Unlike Cheddar or Parmesan, Gruyère’s aging focuses on enhancing its functionality in cooking while maintaining a balanced flavor profile. A caution: overcooking can cause oiling out, so monitor heat levels when using it in recipes.

Beyond these classics, aged cheeses like Manchego (Spain, 6–12 months), Pecorino Romano (Italy, 8–12 months), and Comté (France, 4–24 months) offer further diversity. Each reflects its region’s traditions and aging techniques, from Manchego’s sheep’s milk richness to Comté’s fruity, hazelnut undertones. The takeaway? Aged cheese is a culinary journey, where time, technique, and terroir converge to create unparalleled flavors and textures. Experiment with different varieties to discover how aging transforms the ordinary into the extraordinary.

Milk Sensitivity vs. Cheese Tolerance: Unraveling the Dairy Dilemma

You may want to see also

Flavor Development: Aging intensifies taste, adding nuttiness, sharpness, or sweetness to the cheese

Aged cheese is a testament to the transformative power of time, where patience yields complexity. As cheese matures, its flavor profile deepens, revealing layers of nuttiness, sharpness, or sweetness that were dormant in its younger state. This evolution is not random but a deliberate process guided by microbial activity, moisture loss, and enzymatic reactions. For instance, a young cheddar may present a mild, creamy character, but after 12 to 24 months of aging, it develops a pronounced tang and a crumbly texture, with notes of toasted nuts and caramel emerging prominently.

To understand how aging intensifies flavor, consider the role of enzymes and bacteria. During aging, enzymes break down proteins into amino acids and fats into fatty acids, both of which contribute to the cheese’s taste. In hard cheeses like Parmigiano-Reggiano, aging for 24 months or more results in a crystalline texture and a savory umami flavor, often described as brothy or meaty. Similarly, in blue cheeses, such as Roquefort or Stilton, aging allows the Penicillium mold to develop, creating a pungent, spicy profile that balances sweetness and sharpness. The longer the cheese ages, the more concentrated these flavors become, as moisture evaporates, leaving behind a denser, more potent product.

Practical tips for appreciating aged cheese include pairing it with complementary flavors. A sharply aged Gouda, aged for 18 months or more, pairs beautifully with a sweet dessert wine or a dark beer, as its caramelized notes are enhanced by the contrast. For those new to aged cheeses, start with moderately aged varieties, such as a 6-month aged Gruyère, which offers a balance of nutty and slightly salty flavors without overwhelming intensity. When serving, allow the cheese to come to room temperature to fully express its developed flavors.

Comparatively, the aging process in cheese mirrors that of wine or whiskey, where time is a critical factor in flavor development. However, cheese aging is more dynamic, as it involves both internal chemistry and external conditions like humidity and temperature. For example, a cheese aged in a cave will develop different flavors than one aged in a controlled environment due to the unique microbial flora present. This variability makes aged cheese a fascinating subject for exploration, as each wheel tells a story of its origin and maturation.

In conclusion, aging is not merely a preservation method but an art that elevates cheese from a simple dairy product to a complex culinary experience. Whether you’re a connoisseur or a casual enthusiast, understanding how aging intensifies flavor allows you to appreciate the craftsmanship behind each bite. From the subtle nuttiness of an aged Swiss to the bold sharpness of an extra-sharp cheddar, aged cheese offers a spectrum of tastes that reward the patient palate.

Quick Thawing Tips for Perfectly Creamy Cheesecake Every Time

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Texture Changes: From soft to hard, crumbly to crystalline, texture evolves during aging

Aged cheeses undergo a remarkable transformation in texture, a process as fascinating as it is delicious. This evolution is a direct result of moisture loss and the breakdown of proteins and fats over time. Imagine a young, supple Brie, its interior oozing with creamy richness. As it ages, it gradually firms up, becoming a denser, more concentrated version of itself. This journey from soft to hard is not linear; it’s a spectrum, with cheeses like Cheddar transitioning from pliable to crumbly, and others, like Parmigiano-Reggiano, developing a granular, crystalline structure that crackles on the tongue.

To understand this process, consider the role of enzymes and bacteria. During aging, enzymes break down proteins into amino acids and peptides, while bacteria consume lactose, producing lactic acid. This acidification causes the milk proteins (primarily casein) to tighten and shrink, expelling moisture. For example, a young Gouda at 6 months retains a smooth, supple texture with about 45% moisture content. By 24 months, it loses nearly half its moisture, becoming harder, drier, and more brittle, with a moisture content below 35%. This dehydration is key to texture changes, as the cheese matrix becomes more compact and less pliable.

Not all aged cheeses follow the same path. Some, like aged Gouda or Comté, develop a slightly granular texture due to tyrosine crystals—tiny, crunchy deposits formed as proteins break down. These crystals are a sign of long aging and add a desirable nutty, umami flavor. In contrast, cheeses like Pecorino Romano become so hard they’re nearly uncuttable with a knife, ideal for grating. The crumbly texture of aged Cheddar, on the other hand, results from the breakdown of fat globules and protein networks, creating a friable structure that melts smoothly when heated.

Practical tips for appreciating texture evolution: pair younger, softer cheeses with fresh fruits or crusty bread to highlight their creaminess. For harder, crystalline cheeses, serve them at room temperature to enhance their crunch and complexity. When cooking, use aged cheeses like Parmesan for grating over pasta, where their dry, granular texture adds a burst of flavor. For sandwiches or burgers, opt for crumbly cheeses like aged Cheddar, which provide a satisfying contrast to softer ingredients. Understanding these textures not only deepens your appreciation but also guides better pairing and usage in culinary applications.

The takeaway is that texture in aged cheese is a dynamic, intentional feature, not a random outcome. It’s a testament to the interplay of time, microbiology, and craftsmanship. From the creamy decadence of youth to the crystalline crunch of maturity, each stage offers a unique sensory experience. By recognizing these changes, you can select cheeses that match your palate or recipe needs, turning a simple meal into a journey through the art of aging.

Why 'Cheez-Its' Stays Singular: The Snack Name Mystery Unpacked

You may want to see also

Health Benefits: Higher protein, lower lactose, and probiotics make aged cheese a healthier option

Aged cheese, with its complex flavors and firm textures, offers more than just a culinary delight—it’s a nutritional powerhouse. As cheese ages, its protein content increases, making it a denser source of this essential macronutrient. For instance, a 1-ounce serving of aged cheddar provides approximately 7 grams of protein, compared to 6 grams in younger cheeses like mozzarella. This higher protein content supports muscle repair, satiety, and overall energy levels, making aged cheese an excellent snack or addition to meals, especially for those aiming to boost their protein intake without consuming large portions.

One of the most significant health advantages of aged cheese lies in its reduced lactose content. During the aging process, lactose—a sugar found in milk—breaks down, leaving behind minimal amounts. This makes aged cheeses like Parmesan, Gruyère, and Gouda ideal for individuals with lactose intolerance. A study published in the *Journal of Nutrition* found that aged cheeses contain less than 0.5 grams of lactose per serving, a negligible amount that is generally well-tolerated. For context, a glass of milk contains around 12 grams of lactose, highlighting the dramatic difference.

Beyond protein and lactose, aged cheese is a natural source of probiotics, particularly in varieties like aged Gouda and Swiss Emmental. These beneficial bacteria, such as *Lactobacillus* and *Bifidobacterium*, support gut health by promoting a balanced microbiome. Probiotics aid digestion, enhance nutrient absorption, and even bolster the immune system. Incorporating a small portion of aged cheese—about 1–2 ounces daily—can contribute to a healthier gut without overwhelming calorie intake. Pair it with fiber-rich foods like apples or whole-grain crackers for optimal digestive benefits.

When considering aged cheese as a healthier option, portion control is key. While its nutritional profile is impressive, aged cheeses are calorie-dense, with 1 ounce typically containing 100–120 calories. Moderation ensures you reap the benefits without overindulging. For children and older adults, aged cheese can be a convenient way to meet protein and calcium needs, but it’s essential to balance it with other nutrient sources. For example, a small cube of aged cheddar paired with a handful of nuts provides a well-rounded snack rich in protein, healthy fats, and minerals.

Incorporating aged cheese into your diet is simple and versatile. Grate Parmesan over salads for a protein boost, melt Gruyère into soups for added depth, or enjoy a slice of aged Gouda as a post-meal treat. Its longevity—many aged cheeses keep for weeks in the fridge—makes it a practical staple for health-conscious individuals. By choosing aged cheese, you’re not just savoring a gourmet experience but also making a smart choice for your body’s nutritional needs.

Cheese Ownership: Unraveling the Quirky Concept of Personal Cheese Belonging

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

An aged cheese is a type of cheese that has been matured or stored for an extended period, allowing it to develop complex flavors, textures, and aromas through natural processes like fermentation and enzymatic activity.

The aging time for cheese varies widely depending on the type, ranging from a few weeks to several years. For example, cheddar may age for 2 months to 5 years, while Parmesan can age for over 12 months.

During aging, cheese loses moisture, becomes firmer, and develops deeper, more intense flavors. Bacteria and molds break down proteins and fats, creating unique taste profiles and textures.

Aged cheeses are generally lower in lactose, making them easier to digest for those with lactose intolerance. They also tend to be higher in protein and calcium but are often richer in fat and calories compared to fresh cheeses.

Popular aged cheeses include Parmesan, Cheddar, Gouda, Gruyère, and Blue Cheese. Each has distinct characteristics due to their specific aging processes and production methods.