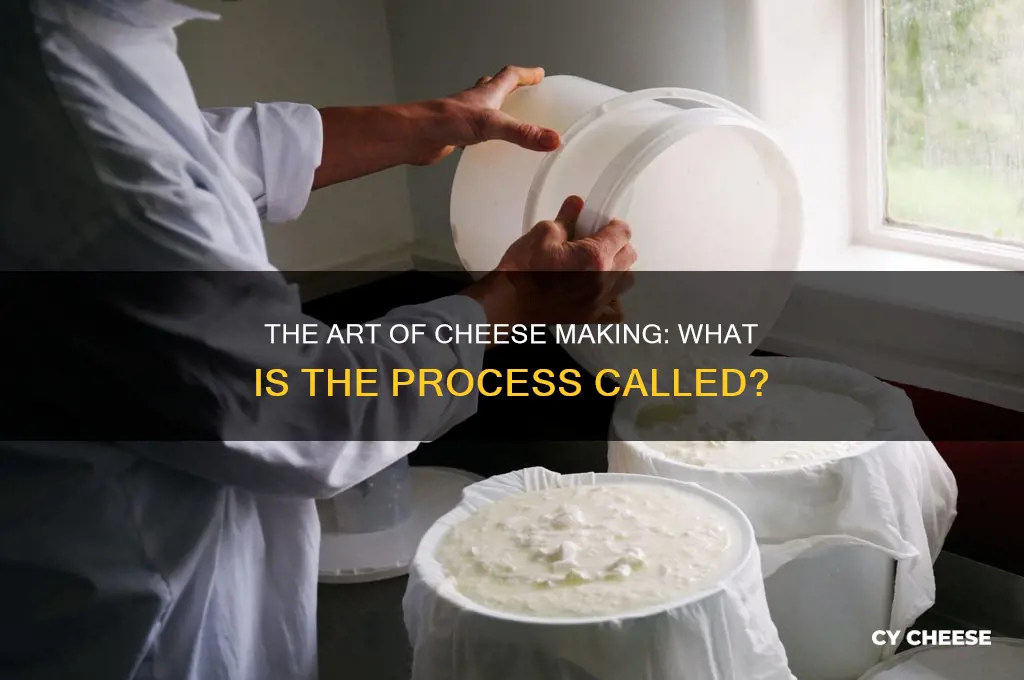

Cheesemaking, also known as caseiculture, is the intricate process of transforming milk into cheese through a series of steps involving coagulation, curdling, and aging. This ancient craft, practiced for thousands of years, combines science and artistry to create a diverse array of cheeses, each with its unique flavor, texture, and aroma. The process typically begins with the addition of rennet or bacterial cultures to milk, causing it to curdle and separate into solids (curds) and liquid (whey). These curds are then pressed, salted, and aged, allowing microorganisms and enzymes to develop the cheese’s characteristic qualities. Whether crafting a creamy Brie or a sharp Cheddar, cheesemaking remains a revered tradition that bridges culinary heritage and innovation.

Explore related products

$14.05 $17.49

What You'll Learn

- Curdling Process: Coagulating milk to separate curds and whey, essential for cheese formation

- Rennet Usage: Enzyme addition to milk to speed up curdling and texture development

- Culturing Milk: Introducing bacteria to ferment milk, creating flavor and acidity

- Pressing Curds: Removing excess whey by applying pressure to form cheese structure

- Aging Cheese: Ripening cheese over time to enhance flavor, texture, and complexity

Curdling Process: Coagulating milk to separate curds and whey, essential for cheese formation

The curdling process is the cornerstone of cheese making, transforming liquid milk into the solid foundation of cheese. This critical step involves coagulating milk to separate it into curds (the solid part) and whey (the liquid part). Without this separation, cheese as we know it cannot form. The process is both a science and an art, relying on precise conditions and careful manipulation to achieve the desired texture and flavor.

Analytical Perspective: Coagulation occurs when milk proteins, primarily casein, are destabilized and aggregate. This can be triggered by acidification (using acids like vinegar or lemon juice) or enzymatic action (using rennet or microbial transglutaminase). Acidification lowers the milk’s pH, causing proteins to lose their negative charge and clump together. Enzymes, on the other hand, cleave specific bonds in the casein micelles, initiating a rapid and controlled curdling process. The choice of method depends on the type of cheese being made—acid-coagulated cheeses (like ricotta) are softer and more delicate, while rennet-coagulated cheeses (like cheddar) are firmer and more complex.

Instructive Approach: To initiate curdling at home, start with high-quality, non-homogenized milk for better results. Heat the milk to 30–35°C (86–95°F), then add 1–2 drops of liquid rennet per liter of milk, diluted in cool water. Stir gently for 1–2 minutes, then let the mixture rest undisturbed for 10–60 minutes, depending on the recipe. For acid coagulation, add 1–2 tablespoons of vinegar or lemon juice per liter of milk, stirring until curds form. Once curds and whey separate, use a slotted spoon or cheesecloth to gently remove the curds, being careful not to break them excessively.

Comparative Insight: The curdling process in cheese making parallels the natural souring of milk but is controlled to produce specific outcomes. While spoiled milk curdles due to bacterial overgrowth and uncontrolled acidification, cheese making employs deliberate techniques to achieve consistency. For example, traditional cheeses like feta use a combination of rennet and bacterial cultures to create a firm yet crumbly texture, whereas fresh cheeses like paneer rely solely on acid coagulation for a soft, crumbly structure. Understanding these differences highlights the versatility of the curdling process across cheese varieties.

Descriptive Takeaway: Watching milk curdle is a mesmerizing transformation—a smooth, uniform liquid gradually gives way to distinct curds floating in translucent whey. This visual shift signals the birth of cheese, a testament to the precision of the curdling process. The curds, initially delicate and fragile, will eventually be cut, heated, and pressed to expel more whey and develop the cheese’s final texture. This step is where the cheese maker’s skill shines, as subtle adjustments in temperature, acidity, or timing can dramatically alter the end product. Mastery of the curdling process is essential for anyone seeking to craft cheese with intention and excellence.

Does Cheese Go Bad? Understanding Expiration Dates on Cheese Blocks

You may want to see also

Rennet Usage: Enzyme addition to milk to speed up curdling and texture development

Cheese making, or caseiculture, involves a delicate interplay of science and art, where milk transforms into a diverse array of cheeses. Central to this process is rennet, a complex of enzymes that accelerates curdling and shapes the final texture. Derived from animal sources or microbial cultures, rennet contains chymosin, the primary enzyme responsible for coagulating milk proteins. Without it, curd formation would be sluggish and unpredictable, underscoring rennet’s role as a cornerstone of efficient cheese production.

Dosage precision is critical when adding rennet to milk. Typically, 1–2 drops of liquid rennet per gallon of milk (or 1/8–1/4 teaspoon of diluted rennet) suffice for most cheeses. Overuse can lead to bitter flavors or excessively firm curds, while underuse results in weak curds that fail to hold structure. Temperature matters too: milk should be warmed to 30–35°C (86–95°F) before rennet addition, as cooler temperatures hinder enzyme activity. Stir gently for 1–2 minutes to distribute rennet evenly, then let the milk rest undisturbed for 30–60 minutes to allow curdling.

For those seeking alternatives, microbial rennet or plant-based coagulants like fig tree bark extract offer viable options, especially for vegetarian cheeses. However, these alternatives may yield slightly different textures or require adjusted dosages. For instance, microbial rennet often works best at slightly higher temperatures (35–40°C) and may take longer to set curds. Experimentation is key to mastering these substitutes, ensuring they align with desired cheese characteristics.

Texture development is where rennet’s magic truly shines. By cleaving kappa-casein proteins, rennet allows calcium to strengthen curd bonds, creating a matrix that determines the cheese’s final consistency. Soft cheeses like mozzarella require minimal rennet for a delicate curd, while hard cheeses like cheddar demand more to achieve a firm, sliceable texture. Understanding this relationship empowers cheesemakers to tailor rennet usage to their vision, whether crafting a creamy brie or a crumbly feta.

In practice, troubleshooting rennet-related issues is essential. If curds fail to set, verify milk temperature and rennet freshness, as expired enzymes lose potency. Conversely, if curds are too rubbery, reduce rennet quantity or adjust milk acidity. For home cheesemakers, keeping a log of rennet type, dosage, and outcomes can refine techniques over time. With patience and precision, rennet becomes not just an ingredient, but a tool for transforming milk into a masterpiece.

Is Raclette a Cheese? Unraveling the Melty Mystery of Raclette

You may want to see also

Culturing Milk: Introducing bacteria to ferment milk, creating flavor and acidity

Cheese making, often referred to as cheesemaking, begins with a transformative process: culturing milk. This step is where the magic happens, as specific bacteria are introduced to ferment the milk, breaking down lactose into lactic acid. This not only preserves the milk but also creates the foundational flavors and acidity essential for cheese. Without culturing, there would be no cheese—only milk.

The process starts with selecting the right bacteria, known as starter cultures. These cultures are carefully measured and added to the milk at precise temperatures, typically between 86°F and 100°F (30°C to 38°C), depending on the cheese variety. For example, mesophilic cultures thrive at lower temperatures (around 86°F) and are used for cheeses like cheddar and mozzarella, while thermophilic cultures prefer higher temperatures (up to 100°F) and are essential for hard cheeses like Gruyère and Parmesan. The dosage of these cultures is critical—usually 1-2% of the milk’s weight—to ensure proper fermentation without overpowering the milk’s natural characteristics.

As the bacteria ferment the milk, they produce lactic acid, which lowers the pH and causes the milk to curdle. This acidity is a double-edged sword: too little, and the cheese lacks flavor; too much, and the curds become too soft or bitter. Monitoring the pH during culturing is key, with most cheeses aiming for a pH range of 5.0 to 6.0. For instance, a pH of 5.4 is ideal for cheddar, while a slightly higher pH of 5.6 works for Gouda. This delicate balance is what distinguishes a well-crafted cheese from a mediocre one.

Practical tips for successful culturing include using high-quality, fresh milk to ensure the bacteria have ample nutrients to thrive. Stirring the milk gently after adding the cultures helps distribute them evenly, preventing uneven fermentation. Additionally, maintaining a consistent temperature throughout the process is crucial; fluctuations can slow or halt fermentation. For home cheesemakers, investing in a reliable thermometer and a warm, draft-free space can make all the difference.

In essence, culturing milk is both a science and an art. It’s the first step in transforming humble milk into a complex, flavorful cheese. By understanding the role of bacteria, controlling temperature and pH, and following precise techniques, anyone can master this foundational process. Whether you’re making a simple ricotta or a complex blue cheese, culturing milk is where the journey begins—and where the true character of the cheese is born.

Transforming Fresh Cheese into Sharp Cheese: A Step-by-Step Aging Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Pressing Curds: Removing excess whey by applying pressure to form cheese structure

Cheese making, or caseiculture, involves a series of precise steps to transform milk into a solid, flavorful product. Among these, pressing curds is a critical phase where excess whey is expelled, and the cheese begins to take its final shape. This step is not merely about removing liquid; it’s about building texture, density, and structure, which vary dramatically depending on the cheese type. For example, a soft cheese like Brie requires minimal pressing, while a hard cheese like Parmesan demands intense pressure over hours or even days.

Steps to Press Curds Effectively:

- Prepare the Curds: After cutting and heating, allow the curds to settle and release whey naturally. For harder cheeses, ensure the curds are firm and matte, not shiny, indicating proper acidity and moisture levels.

- Choose the Right Press: Use a cheese press with adjustable weights or a DIY setup with heavy objects (e.g., canned goods) on a draining mold. For soft cheeses, a light press or weighted plate suffices.

- Apply Pressure Gradually: Start with low pressure (2-5 kg) for the first hour, then increase incrementally. For semi-hard cheeses like Cheddar, aim for 10-15 kg over 4-6 hours. Hard cheeses like Gruyère may require 20-30 kg for 12-24 hours.

- Monitor and Flip: Check every 1-2 hours, flipping the cheese to ensure even moisture removal. Use cheesecloth to prevent sticking and absorb whey.

Cautions to Avoid Common Mistakes:

Over-pressing can lead to cracks or an overly dense texture, while under-pressing leaves excess whey, causing spoilage. Always follow recipes for specific pressure and time guidelines. For example, pressing fresh mozzarella for more than 30 minutes at 2 kg risks a rubbery texture. Additionally, avoid using metal weights directly on the curds, as they can react with acidity and affect flavor.

Practical Tips for Success:

- For even pressing, use a follower (a flat, perforated disk) to distribute weight evenly.

- Keep the pressing area cool (18-22°C) to slow bacterial activity and prevent spoilage.

- For aged cheeses, press in stages, allowing the curds to rest between sessions to relax and bind properly.

Pressing curds is both art and science, requiring attention to detail and patience. By mastering this step, you control the cheese’s final texture and moisture content, ensuring it meets the desired profile. Whether crafting a creamy Camembert or a crumbly Cheshire, the right pressure at the right time transforms curds into a cohesive, delicious cheese.

White vs. Orange American Cheese: Unraveling the Color and Flavor Differences

You may want to see also

Aging Cheese: Ripening cheese over time to enhance flavor, texture, and complexity

Cheese making, known as fromagerie or cheesemaking, encompasses a range of processes, but aging—or ripening—stands out as the transformative phase that elevates cheese from basic to extraordinary. This stage, often overlooked by casual consumers, is where time, temperature, and microbial activity converge to develop depth, complexity, and character. Without aging, many cheeses would remain bland, crumbly, or lacking the nuanced flavors and textures we cherish.

Consider the difference between fresh mozzarella and aged Parmigiano-Reggiano. The former is mild and soft, while the latter is sharp, granular, and intensely savory—a result of 12 to 36 months of aging. Ripening isn’t merely a waiting game; it’s a controlled process where enzymes break down proteins and fats, releasing amino acids and fatty acids that contribute to flavor. Humidity, airflow, and temperature play critical roles: a cave-aged Gruyère, for instance, requires 50–70% humidity and 45–55°F (7–13°C) to develop its signature nutty notes and eyes (holes).

To age cheese at home, start with a hard or semi-hard variety like cheddar or Gouda. Store it in a refrigerator crisper drawer or a wine cooler set to 50–55°F (10–13°C) with 80–85% humidity. Wrap the cheese in cheese paper or parchment, not plastic, to allow it to breathe. Flip it weekly to prevent mold concentration, and monitor for unwanted growth. For advanced hobbyists, a DIY aging box with a humidifier and thermometer can replicate professional conditions.

The timeline for aging varies by cheese type. A young cheddar may ripen in 2–6 months, while a complex Alpine cheese like Comté can take 6–24 months. Taste regularly to track progress—flavor should deepen, texture should firm, and aromas should evolve from milky to earthy, fruity, or even pungent. Patience is key; rushing the process risks uneven ripening or off-flavors.

Aging cheese is both art and science, demanding precision and intuition. It’s a testament to how time, when harnessed thoughtfully, can turn simplicity into sophistication. Whether you’re a maker or a connoisseur, understanding ripening reveals the craftsmanship behind every bite.

Best Cheese Plates in Hattiesburg, MS: Top Restaurant Picks

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Cheese making is called cheesemaking or caseiculture, derived from the Latin word *caseus* meaning cheese.

Yes, the art of cheese making is often referred to as fromagerie, which also denotes a place where cheese is made or sold.

The technical process of cheese making is called coagulation and curdling, as it involves curdling milk to separate curds and whey.

Yes, for example, in French, cheese making is called fabrication du fromage, and in Italian, it is known as produzione di formaggio.