The term cheese refers to a diverse group of dairy products made from the milk of cows, goats, sheep, or other animals, through a process of curdling, draining, and aging. Derived from the Latin word caseus, cheese has been a staple in human diets for thousands of years, with evidence of its production dating back to ancient civilizations. The term encompasses a wide range of varieties, each with unique flavors, textures, and aromas, influenced by factors such as milk type, bacterial cultures, aging time, and production techniques. Understanding the term cheese involves exploring its historical significance, cultural importance, and the intricate processes that transform milk into this beloved and versatile food.

Explore related products

$21.87 $23.35

What You'll Learn

- Types of Cheese: Categorized by texture, milk source, aging, and production methods

- Cheese Aging Process: Transforms flavor, texture, and appearance over time

- Cheese Pairings: Matches with wine, fruits, nuts, and other foods

- Cheese Making Steps: Curdling, pressing, salting, and ripening milk into cheese

- Cheese Terminology: Common terms like rind, pasteurized, artisanal, and brined explained

Types of Cheese: Categorized by texture, milk source, aging, and production methods

Cheese, a culinary chameleon, transforms dramatically based on its texture, milk source, aging process, and production methods. Understanding these categories unlocks a world of flavor and pairing possibilities.

Let's delve into the fascinating world of cheese classification.

Texture: From Crumbly to Creamy

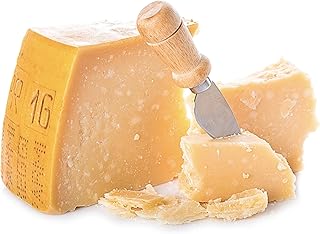

Imagine a spectrum: at one end, the dry, crumbly feta, perfect for salads and adding a salty tang. At the other, the luxuriously creamy Brie, oozing decadence and begging for a crusty baguette. In between lies a symphony of textures: semi-soft Cheddar, ideal for melting onto burgers, and semi-hard Gruyère, adding depth to soups and sauces. Hard cheeses like Parmesan, aged to a granular perfection, grate beautifully over pasta, while fresh cheeses like mozzarella, with their delicate, moist texture, star in caprese salads.

Milk Source: A Symphony of Flavors

The animal providing the milk significantly influences a cheese's character. Cow's milk cheeses, like Cheddar and Gouda, offer a familiar, buttery richness. Goat's milk cheeses, such as Chèvre and Feta, bring a tangy, slightly acidic note, often with a crumbly texture. Sheep's milk cheeses, like Manchego and Pecorino, are known for their nutty, earthy flavors and firmer textures. Buffalo milk, used in Mozzarella di Bufala, lends a uniquely rich, creamy mouthfeel.

Aging: Time's Transformative Touch

Aging is the alchemist's touch, transforming fresh curds into complex, flavorful cheeses. Fresh cheeses, like ricotta and cottage cheese, are minimally aged, retaining a mild, delicate flavor. Semi-soft cheeses, aged for a few weeks to months, develop deeper flavors and a softer texture, as seen in Havarti and Muenster. Hard cheeses, aged for months or even years, become firm, nutty, and sometimes crystalline, like Parmesan and aged Gouda. Blue cheeses, inoculated with Penicillium mold, develop distinctive veins and a pungent, spicy flavor profile.

Production Methods: Artistry in Action

Beyond milk and aging, production methods further refine a cheese's identity. Pasteurization, heating milk to kill bacteria, is common, but raw milk cheeses, made from unpasteurized milk, are prized for their complex flavors. Rennet, an enzyme, is traditionally used to curdle milk, but vegetarian alternatives are increasingly popular. The way curds are cut, heated, pressed, and molded all contribute to a cheese's final texture and character. From the washed rinds of Limburger to the smoked flavors of Gouda, these techniques add layers of complexity to the cheese-making art.

Is Shepherd's Hope a Cheese? Unraveling the Mystery Behind the Name

You may want to see also

Cheese Aging Process: Transforms flavor, texture, and appearance over time

The cheese aging process, often referred to as affinage, is a meticulous art that transforms a simple curd into a complex, flavorful masterpiece. During this period, which can range from a few weeks to several years, cheese undergoes profound changes in flavor, texture, and appearance. For instance, a young cheddar is mild and supple, but after 12 to 24 months, it develops a sharp, tangy profile and a crumbly texture. This transformation is driven by microbial activity, enzyme breakdown, and moisture loss, all of which occur in carefully controlled environments.

To understand the aging process, consider the role of temperature and humidity. Most cheeses age in caves or specialized rooms where temperature is maintained between 50°F and 55°F (10°C and 13°C), and humidity levels hover around 85-95%. These conditions encourage the growth of beneficial molds and bacteria, such as *Penicillium camemberti* in Camembert or *Brevibacterium linens* in Limburger. For example, a wheel of Brie aged for 4 to 6 weeks develops a bloomy rind and a creamy interior, while the same cheese aged for 8 weeks becomes richer and more unctuous, with a pronounced ammonia aroma.

Practical tips for home aging include investing in a wine fridge or a cooler with humidity control. Start with semi-hard cheeses like Gouda or Gruyère, which are forgiving and develop desirable crystalline tyrosine structures over 6 to 12 months. Wrap the cheese in cheese paper or parchment, not plastic, to allow it to breathe. Regularly flip the wheel to ensure even moisture distribution and prevent mold overgrowth. For blue cheeses, pierce the interior with skewers to introduce oxygen, fostering vein development.

Comparatively, the aging process in hard cheeses like Parmigiano-Reggiano is far more rigorous. These cheeses are aged for a minimum of 12 months, often up to 36 months, during which they lose 30-40% of their moisture. This concentration intensifies flavors and creates a granular, brittle texture. In contrast, fresh cheeses like mozzarella or chèvre are minimally aged, if at all, to preserve their mild, milky character. Understanding these differences highlights how aging duration and conditions dictate a cheese’s final identity.

The takeaway is that the cheese aging process is both a science and an art, requiring patience, precision, and a keen sensory palate. Whether you’re a home enthusiast or a professional affineur, mastering this process unlocks a world of flavors and textures. Experiment with aging times and conditions to discover how a single cheese can evolve into multiple distinct personalities, each with its own story to tell.

Does Stromboli Have Cheese? Unraveling the Cheesy Truth Inside

You may want to see also

Cheese Pairings: Matches with wine, fruits, nuts, and other foods

Cheese pairings elevate the sensory experience, transforming simple ingredients into a symphony of flavors. The key lies in balancing textures, intensities, and complementary notes. For instance, a sharp cheddar’s nuttiness pairs brilliantly with a crisp apple, while a creamy Brie finds its match in the sweetness of fresh figs. Understanding these dynamics unlocks endless possibilities for both casual snacking and sophisticated entertaining.

When pairing cheese with wine, consider the rule of regional affinity—cheeses often harmonize with wines from the same area. A bold Cabernet Sauvignon complements the richness of aged Gouda, while a light, fruity Riesling enhances the tanginess of goat cheese. For a foolproof approach, match intensity levels: mild cheeses like mozzarella pair well with lighter wines, while robust blues like Stilton stand up to full-bodied ports. Serving temperature matters too; chill whites slightly less than usual to avoid overpowering delicate cheeses.

Fruits and nuts introduce contrasting textures and flavors that highlight cheese’s versatility. The crunch of toasted almonds alongside creamy Camembert adds depth, while the juiciness of pears softens the saltiness of Manchego. For a sweet-savory contrast, drizzle honey over blue cheese and pair it with walnut halves. When creating a cheese board, arrange pairings in a clockwise progression from mild to strong, allowing guests to explore flavors systematically without overwhelming their palate.

Beyond the classics, experiment with unconventional pairings to discover unexpected delights. Try sharp Parmesan with dark chocolate for a savory-sweet interplay, or crumble feta over watermelon and mint for a refreshing summer bite. For a hearty option, pair melted raclette with cured meats and cornichons. The goal is to create balance—whether through mirroring flavors or introducing contrasts—ensuring each element enhances rather than overshadows the other.

Practical tips can streamline the pairing process. Start with small portions to avoid waste and encourage exploration. Label cheeses and pairings for clarity, especially when serving guests with dietary restrictions. For aging cheeses, allow them to come to room temperature for optimal flavor, but serve fresh cheeses chilled to maintain their texture. Finally, trust your taste buds—while guidelines are helpful, personal preference ultimately dictates the perfect pairing.

Mastering Cheese Strategies for Maniac Bird Cat Battles in Battle Cats

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Cheese Making Steps: Curdling, pressing, salting, and ripening milk into cheese

Cheese making is a transformative process that turns milk into a diverse array of flavors, textures, and aromas. At its core, the journey from milk to cheese involves four fundamental steps: curdling, pressing, salting, and ripening. Each stage is critical, requiring precision and patience to achieve the desired outcome. Understanding these steps not only demystifies the art of cheese making but also empowers enthusiasts to experiment with their own creations.

Curdling: The Foundation of Cheese

The first step, curdling, is where milk transitions from liquid to solid. This process involves adding a coagulant, such as rennet or acid (e.g., lemon juice or vinegar), to milk. The coagulant causes the milk proteins (casein) to bind together, forming curds (solid masses) and whey (liquid). For example, hard cheeses like cheddar typically use rennet, while soft cheeses like ricotta often rely on acid. Temperature control is crucial here—milk heated to 30–35°C (86–95°F) ensures optimal curd formation. Overheating can toughen the curds, while underheating may prevent proper coagulation. The curdling stage sets the stage for the cheese’s texture and structure, making it a cornerstone of the process.

Pressing: Shaping Texture and Moisture

Once curds form, pressing removes excess whey and consolidates the curds into a cohesive mass. The pressure applied and duration vary by cheese type. For instance, fresh cheeses like mozzarella require minimal pressing, while hard cheeses like Parmesan are pressed under heavy weights for hours or even days. Pressing not only shapes the cheese but also influences its moisture content and density. A practical tip: use cheese molds with holes to allow whey to drain efficiently. Improper pressing can lead to uneven texture or unwanted pockets of whey, so consistency is key.

Salting: Flavor and Preservation

Salting is more than just seasoning—it’s a preservative and a flavor enhancer. Salt can be applied directly to the curds or added to the brine in which the cheese soaks. The method depends on the cheese variety. For example, feta is brined for several weeks, while cheddar is dry-salted and flipped regularly. The salt concentration typically ranges from 1.5% to 3% of the cheese’s weight. Salting also slows bacterial growth, extending shelf life. Over-salting can overpower the cheese’s natural flavors, so measure carefully and taste as you go.

Ripening: Developing Character

Ripening, or aging, is where cheese develops its unique flavor, aroma, and texture. During this stage, bacteria and molds break down proteins and fats, creating complex compounds. Ripening conditions—temperature, humidity, and duration—vary widely. Soft cheeses like Brie may age for 2–4 weeks at 12°C (54°F) and 90% humidity, while aged cheeses like Gruyère can mature for 6–12 months in cooler, drier environments. Regularly flipping and brushing the cheese prevents mold overgrowth and ensures even ripening. Patience is paramount here; rushing the process can result in underdeveloped flavors or undesirable textures.

In mastering these steps—curdling, pressing, salting, and ripening—one gains the ability to craft cheese with intention and creativity. Each stage offers opportunities for customization, from the choice of milk and coagulant to the aging environment. Whether you’re a novice or an experienced cheesemaker, understanding these fundamentals transforms the process from alchemy to art.

Elegant Cheese Displays: A Step-by-Step Guide for Reception Setup

You may want to see also

Cheese Terminology: Common terms like rind, pasteurized, artisanal, and brined explained

Cheese, a beloved food with a rich history, comes with its own vocabulary that can be both fascinating and confusing. Understanding key terms like rind, pasteurized, artisanal, and brined not only enhances your appreciation of cheese but also empowers you to make informed choices. Let’s break these terms down, starting with the often-misunderstood rind.

The rind is the outer layer of a cheese, acting as a protective barrier during aging. It can vary widely in texture, from the thin, delicate skin of a fresh chèvre to the thick, hard crust of a Parmigiano-Reggiano. Rinds are not always meant to be eaten—some are purely functional, while others contribute to flavor and texture. For example, the bloomy rind of a Brie, covered in white mold, is edible and adds a rich, earthy note. When selecting cheese, consider whether the rind is part of the experience or if it should be trimmed.

Next, pasteurized cheese refers to cheese made from milk heated to a specific temperature (typically 161°F for 15 seconds) to kill harmful bacteria. This process ensures safety, particularly for pregnant individuals or those with weakened immune systems. However, pasteurization can alter the milk’s natural enzymes and microbes, sometimes affecting flavor complexity. Raw milk cheeses, on the other hand, retain these elements, often resulting in deeper, more nuanced flavors. Always check labels if pasteurization is a concern for your health or culinary goals.

The term artisanal has become a buzzword in the cheese world, but what does it truly mean? Artisanal cheeses are crafted in small batches, often using traditional methods and high-quality, locally sourced milk. Unlike mass-produced cheeses, artisanal varieties prioritize unique flavors and textures over uniformity. For instance, an artisanal cheddar might age for 12–24 months, developing sharp, complex notes, while its factory-made counterpart is often aged for just 60 days. Supporting artisanal cheesemakers not only elevates your cheese board but also sustains local farming communities.

Finally, brined cheeses are soaked or cured in a saltwater solution, which preserves them and imparts a tangy, savory flavor. Feta is a classic example, traditionally brined to achieve its signature crumbly texture and salty kick. Brining also slows spoilage, making these cheeses excellent for long-term storage. If you’re experimenting with brined cheeses, remember to pat them dry before use to avoid overpowering dishes with saltiness.

Understanding these terms transforms cheese from a simple ingredient into a subject of exploration. Whether you’re selecting a rind-on cheese for a charcuterie board, opting for pasteurized varieties for safety, savoring the craftsmanship of artisanal creations, or enjoying the tang of brined cheeses, this knowledge deepens your connection to the food you love. Cheese terminology isn’t just jargon—it’s a gateway to a richer, more mindful culinary experience.

Perfect Cheese Pairings for Your Ultimate Salmon Burger Experience

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The term "curd" refers to the solid mass that forms when milk coagulates during the cheese-making process. It is the basis of cheese, created by the action of rennet or acids on milk proteins.

"Pasteurized" refers to the process of heating milk to a specific temperature to kill harmful bacteria while preserving its suitability for cheese making. This ensures the cheese is safe for consumption.

The "rind" is the outer layer or crust of a cheese, which can form naturally or be added during production. It protects the cheese and can influence its flavor, texture, and appearance.

An "affineur" is a specialist who ages and cares for cheeses, ensuring they develop the desired flavor, texture, and quality. They manage humidity, temperature, and turning during the aging process.

![Fresh Mozzarella Snacking Cheese is a fresh mild-flavored cheese that's perfect for snacking or sandwiches. Just 70 calories each and packed with protein, these individual packages are the ultimate grab-and-go snack. [ 18 oz , 1.12 pound ]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/61LL+nnP4LL._AC_UY218_.jpg)