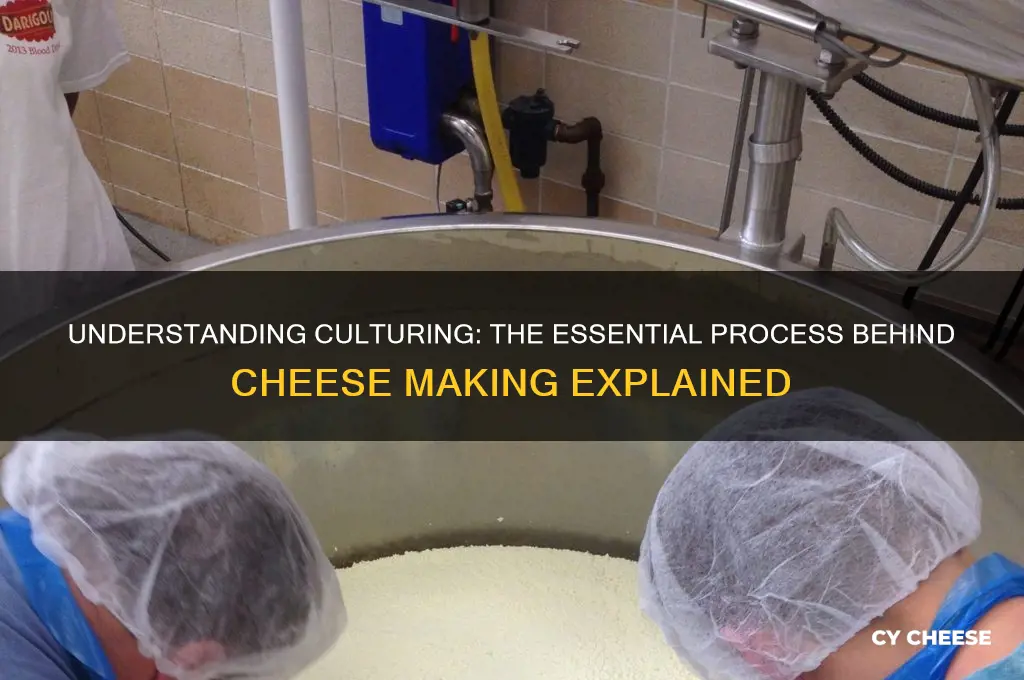

Culturing in cheese is a fundamental process in cheesemaking that involves the use of specific bacteria and sometimes molds to transform milk into cheese. These microorganisms, often referred to as starter cultures, are added to milk to initiate the fermentation process, which lowers the pH and coagulates the milk proteins. This step is crucial as it not only contributes to the texture and structure of the cheese but also develops its distinctive flavors and aromas. Different strains of bacteria and molds can be used to create a wide variety of cheeses, from the mild and creamy to the sharp and pungent, making culturing a key factor in defining the character of the final product.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Culturing in cheese refers to the process of introducing and nurturing specific bacteria and/or molds to transform milk into cheese. These microorganisms ferment lactose (milk sugar) into lactic acid, which coagulates milk proteins and develops flavor, texture, and aroma. |

| Primary Microorganisms | Lactic acid bacteria (e.g., Lactococcus, Lactobacillus, Streptococcus thermophilus), Propionibacterium (for Swiss cheese), Penicillium molds (e.g., Penicillium camemberti, Penicillium roqueforti), and others depending on cheese type. |

| Purpose | 1. Acidification: Lowers pH, causing milk to curdle. 2. Flavor Development: Produces enzymes and metabolites that create unique taste profiles. 3. Texture Formation: Influences moisture content and structure. 4. Preservation: Inhibits harmful bacteria growth. |

| Types of Cultures | Mesophilic (active at 20–40°C, e.g., Cheddar), Thermophilic (active at 40–45°C, e.g., Mozzarella), Mold Cultures (e.g., Brie, Blue Cheese), and Mixed Cultures (combination of bacteria and molds). |

| Stages | 1. Inoculation: Adding starter cultures to milk. 2. Fermentation: Cultures multiply and produce acids/enzymes. 3. Ripening/Aging: Cultures continue to develop flavor and texture over time. |

| Factors Affecting Culturing | Milk type (cow, goat, sheep), temperature, humidity, salt concentration, and duration of aging. |

| Examples of Cultured Cheeses | Cheddar, Camembert, Gouda, Blue Cheese, Parmesan, Feta, and more. |

| Health Benefits | Probiotics (live cultures) in some cheeses may support gut health, depending on the survival of cultures during aging and consumption. |

| Challenges | Contamination by unwanted microorganisms, inconsistent fermentation due to environmental factors, and pH imbalances. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Starter Cultures: Bacteria/fungi added to milk to initiate fermentation, defining cheese flavor and texture

- Ripening Process: Aging cheese to develop complex flavors, textures, and aromas over time

- Culture Types: Mesophilic vs. thermophilic bacteria, each suited for specific cheese varieties

- Culture Role: Converts lactose to lactic acid, coagulating milk and preserving cheese

- Natural Cultures: Using raw milk’s native bacteria for unique, regional cheese characteristics

Starter Cultures: Bacteria/fungi added to milk to initiate fermentation, defining cheese flavor and texture

Cheese begins with milk, but it’s the starter cultures—specific strains of bacteria and fungi—that transform this liquid into a solid, flavorful masterpiece. These microorganisms are the unsung heroes of cheesemaking, initiating fermentation by converting lactose (milk sugar) into lactic acid. This process not only preserves the milk but also creates the foundation for the cheese’s texture and flavor profile. Without starter cultures, cheese would lack its characteristic tang, complexity, and structure.

Consider the precision required in selecting and dosing starter cultures. For example, mesophilic bacteria like *Lactococcus lactis* thrive at moderate temperatures (20–30°C) and are ideal for cheeses like Cheddar or Gouda, while thermophilic bacteria such as *Streptococcus thermophilus* prefer higher temperatures (35–45°C), making them suitable for Swiss or mozzarella. Dosage matters too: a typical inoculation rate is 0.5–2% of the milk volume, but this varies based on the desired acidity and fermentation speed. Too little culture, and fermentation stalls; too much, and the cheese becomes overly acidic or crumbly.

The interplay between bacteria and fungi in starter cultures also shapes cheese diversity. For instance, blue cheeses like Roquefort rely on *Penicillium roqueforti*, a fungus introduced alongside bacterial cultures. This fungus creates the distinctive veins and pungent aroma, while the bacteria contribute to the creamy texture. Similarly, surface-ripened cheeses like Brie use *Penicillium camemberti* in tandem with lactic acid bacteria to develop a bloomy rind and soft interior. Each combination of cultures is a recipe for a unique cheese, highlighting their role as both artists and architects in the process.

Practical tips for home cheesemakers underscore the importance of handling starter cultures with care. Always use fresh cultures, as their viability diminishes over time. Store freeze-dried cultures in the freezer and rehydrate them in sterile, lukewarm milk before adding to the batch. Monitor temperature closely, as deviations can alter fermentation rates and outcomes. For example, a 5°C drop can slow mesophilic cultures, while a spike can stress thermophilic strains. Finally, experiment with single-strain vs. mixed-strain cultures to understand their individual contributions—a single strain might offer a cleaner flavor, while a blend adds complexity.

In essence, starter cultures are the cornerstone of cheese identity, dictating everything from its melt to its bite. They are not just ingredients but catalysts, turning milk into a canvas for flavor and texture. By mastering their use, cheesemakers—whether professionals or hobbyists—can craft products that range from mild and creamy to bold and earthy. The science is precise, but the art lies in understanding how these microscopic organisms can be harnessed to create something extraordinary.

Anti-Caking Secrets: How Additives Keep Shredded Cheese Fresh and Separated

You may want to see also

Ripening Process: Aging cheese to develop complex flavors, textures, and aromas over time

The ripening process, often referred to as aging, is the transformative phase where cheese evolves from a simple curd into a complex, flavorful masterpiece. This stage is where time, temperature, and humidity work in harmony to develop the unique characteristics that define each cheese variety. For instance, a young cheddar aged for 2 months will have a mild, creamy profile, while one aged for 2 years can exhibit sharp, tangy notes with a crumbly texture. Understanding this process allows both cheesemakers and enthusiasts to appreciate the artistry behind every wheel.

To initiate ripening, cheese is typically moved to a controlled environment known as a aging room or cave. Here, temperature and humidity levels are meticulously maintained—ideally between 50–55°F (10–13°C) and 80–90% humidity for most varieties. These conditions encourage the growth of beneficial molds and bacteria, which break down proteins and fats, creating amino acids and fatty acids responsible for flavor development. For example, blue cheeses like Roquefort rely on Penicillium roqueforti to create their distinctive veins and pungent aroma, while hard cheeses like Parmigiano-Reggiano develop their granular texture and nutty flavor through slow aging over 12–36 months.

Aging time varies dramatically depending on the desired outcome. Fresh cheeses like mozzarella or chèvre are consumed within days or weeks, while others, such as Gruyère or Gouda, may age for 6–12 months. Some cheeses, like the Spanish Manchego, are aged for a minimum of 60 days but can extend to a year for a more intense flavor. During this period, cheesemakers often flip and brush the wheels to ensure even moisture distribution and prevent unwanted mold growth. Patience is key—rushing the process can result in unbalanced flavors or undesirable textures.

The ripening process also involves chemical transformations that contribute to aroma and mouthfeel. Lipolysis, the breakdown of fats, releases compounds that add richness and complexity, while proteolysis, the breakdown of proteins, enhances umami and savory notes. For instance, aged Gouda develops a caramelized sweetness due to the Maillard reaction, a chemical process that occurs during prolonged aging. These reactions are why a well-aged cheese can offer a symphony of flavors—earthy, fruity, nutty, or even buttery—that a younger version lacks.

Practical tips for home aging include using a wine fridge or a cooler with a humidity tray to mimic professional conditions. Wrap cheese in wax paper or cheese paper to allow it to breathe, and avoid plastic, which traps moisture and encourages spoilage. Regularly inspect the cheese for unwanted mold or off-odors, and trust your senses—if it smells or tastes off, it’s best discarded. By mastering the ripening process, even amateur cheesemakers can elevate their creations, turning simple ingredients into extraordinary culinary experiences.

Mastering Melty Cheese: Tips to Keep It Gooey and Runny

You may want to see also

Culture Types: Mesophilic vs. thermophilic bacteria, each suited for specific cheese varieties

Cheese culturing relies on bacteria to transform milk into curds and whey, a process as ancient as it is precise. Among the myriad microbial players, two broad categories dominate: mesophilic and thermophilic bacteria. Each thrives in distinct temperature ranges, dictating their suitability for specific cheese varieties. Mesophiles, comfortable at 20–40°C (68–104°F), are the workhorses of softer, milder cheeses like Cheddar and Camembert. Thermophiles, on the other hand, flourish at 40–55°C (104–131°F), essential for crafting harder, more complex cheeses such as Parmesan and Gruyère. Understanding these temperature preferences is the first step in mastering the art of cheese culturing.

Consider the mesophilic bacteria, often added in dosages of 0.5–2% of milk volume, depending on the recipe. These bacteria, such as *Lactococcus lactis*, excel in cooler environments, making them ideal for cheeses that require slower acidification. For instance, in Cheddar production, mesophiles work over 8–12 hours to achieve the desired pH of 4.6–4.8, crucial for proper curd formation. However, their sensitivity to higher temperatures means they must be handled carefully to avoid killing them during pasteurization. A practical tip: always ensure the milk is cooled to below 30°C (86°F) before adding mesophilic cultures to maintain their viability.

Thermophilic bacteria, such as *Streptococcus thermophilus* and *Lactobacillus delbrueckii*, are the champions of high-heat environments. They are typically added at 1–3% of milk volume, depending on the cheese type. These bacteria are indispensable for Swiss-style cheeses like Emmental, where they withstand the elevated temperatures needed for proper curd development. For example, during Gruyère production, thermophiles work at 50–55°C (122–131°F) to produce lactic acid and contribute to the cheese’s distinctive eye formation. Their resilience also makes them ideal for fermented milk products like yogurt, though their primary domain remains thermophilic cheese varieties.

The choice between mesophilic and thermophilic bacteria isn’t just about temperature—it’s about the flavor, texture, and aging potential of the final product. Mesophiles tend to produce milder, buttery flavors, while thermophiles contribute to nuttier, more complex profiles. For instance, the sharp tang of aged Parmesan owes much to the work of thermophiles, whereas the creamy richness of Brie is a testament to mesophilic activity. When experimenting with cheese culturing, consider the desired outcome: a softer, quicker-aging cheese calls for mesophiles, while a harder, longer-aging variety demands thermophiles.

In practice, combining both culture types can yield unique results. For example, in Italian cheeses like Provolone, a blend of mesophilic and thermophilic bacteria is used to balance acidity and flavor development. However, this approach requires careful monitoring, as the temperature must be adjusted to accommodate both cultures. A cautionary note: avoid overheating mesophiles or underheating thermophiles, as this can halt the culturing process entirely. By understanding the strengths and limitations of each culture type, cheesemakers can tailor their techniques to create cheeses that are not only delicious but also distinctly their own.

Discover the Perfect Party Platter: Cheese and Meat Tray Names

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Culture Role: Converts lactose to lactic acid, coagulating milk and preserving cheese

Culturing is the backbone of cheese production, and its primary role is to transform milk into a solid, flavorful cheese. At the heart of this process are bacteria cultures, which perform a crucial task: converting lactose, the natural sugar in milk, into lactic acid. This seemingly simple reaction is the catalyst for a chain of events that coagulates milk, preserves the cheese, and develops its unique flavor profile.

The Science Behind the Transformation

When bacteria cultures are added to milk, they metabolize lactose, producing lactic acid as a byproduct. This acidification lowers the milk’s pH, causing proteins to denature and coagulate. For example, in cheddar cheese, mesophilic cultures (active at 20–30°C) are typically used at a dosage of 0.5–1% of milk volume. This precise balance ensures the milk solidifies into a curd, separating from the whey. Without this step, cheese would remain a liquid, devoid of structure.

Preservation Through Acidification

Lactic acid isn’t just a coagulating agent—it’s a natural preservative. By lowering the pH, it creates an environment hostile to harmful bacteria, extending the cheese’s shelf life. This is why fresh cheeses like mozzarella or ricotta, which use higher doses of cultures (up to 2%), spoil more slowly than uncultured milk. For aged cheeses, such as Parmesan, the gradual acidification during culturing also slows down spoilage, allowing flavors to develop over months or years.

Flavor Development: A Byproduct of Function

While the primary role of cultures is functional, their impact on flavor is undeniable. Different strains of bacteria produce varying levels of lactic acid and other compounds, influencing the cheese’s tanginess, sharpness, or nuttiness. For instance, thermophilic cultures (active at 40–45°C), used in Swiss or Gruyère, create a milder acidity compared to mesophilic cultures. Experimenting with culture types and dosages allows cheesemakers to tailor flavors, proving that culturing is as much an art as it is a science.

Practical Tips for Home Cheesemakers

If you’re culturing cheese at home, precision is key. Always measure culture dosage accurately—too little won’t acidify sufficiently, while too much can lead to a bitter, overly sour cheese. Maintain consistent temperatures, as fluctuations can slow or halt bacterial activity. For fresh cheeses, aim for a pH of 4.6–4.8; for aged varieties, target 5.0–5.4. Finally, use high-quality cultures and store them properly (usually refrigerated at 2–4°C) to ensure viability.

In essence, culturing is where cheese begins—a delicate dance of biology and chemistry that transforms milk into a preserved, flavorful masterpiece. Master this step, and you’ll unlock the secrets to crafting cheese that’s both scientifically sound and delightfully delicious.

Is Provolone a Cheese? Unraveling the Dairy Mystery

You may want to see also

Natural Cultures: Using raw milk’s native bacteria for unique, regional cheese characteristics

Raw milk is a treasure trove of microbial diversity, teeming with native bacteria that impart distinct flavors, textures, and aromas to cheese. These natural cultures, often referred to as the "terroir" of cheese, are the cornerstone of artisanal cheesemaking. By harnessing the indigenous microorganisms present in raw milk, cheesemakers can create products that reflect the unique characteristics of their region, from the grassy notes of Alpine cheeses to the earthy undertones of those from humid climates. This approach not only preserves traditional methods but also elevates cheese to a level of complexity that pasteurized milk, with its standardized bacterial cultures, cannot achieve.

To utilize raw milk’s native bacteria effectively, cheesemakers must first understand the milk’s microbial profile. This involves monitoring factors like pH, temperature, and seasonal variations, as these influence bacterial activity. For instance, milk from cows grazing on spring pastures may contain higher levels of lactic acid bacteria, resulting in a faster acidification process. Dosage is less about precise measurements and more about creating optimal conditions for these bacteria to thrive. A common practice is to allow the milk to sit at room temperature (around 20°C) for several hours, a technique known as "ripening," which encourages the growth of desirable microorganisms. This step is crucial for developing the cheese’s unique flavor profile.

One of the most compelling aspects of using natural cultures is their ability to adapt and evolve. Unlike commercial starter cultures, which are static, raw milk’s bacteria change with the environment, leading to subtle variations in each batch. For example, a cheese made in the same dairy during different seasons may exhibit distinct characteristics due to shifts in the milk’s microbial composition. This unpredictability is both a challenge and a reward, requiring cheesemakers to be attentive and flexible. To maintain consistency, some artisans keep a "mother culture" by reserving a portion of whey from a successful batch, which can be added to future productions to guide the fermentation process.

Practical tips for working with natural cultures include maintaining strict hygiene to prevent unwanted bacteria from dominating and using minimal intervention techniques to let the milk’s native flora take the lead. Cheesemakers should also experiment with aging times, as natural cultures often develop more complex flavors over longer periods. For instance, a raw milk cheese aged for 12 months may exhibit deeper, nuttier notes compared to one aged for only 6 months. This hands-off approach not only honors the milk’s inherent qualities but also fosters a deeper connection between the cheese, its maker, and the land.

In a world increasingly dominated by standardized, mass-produced foods, natural cultures offer a way to celebrate diversity and regional identity. By embracing raw milk’s native bacteria, cheesemakers can craft products that tell a story—one of place, tradition, and craftsmanship. This method is not just about making cheese; it’s about preserving a legacy and offering consumers a taste of something truly unique. For those willing to explore this ancient practice, the rewards are as rich and varied as the cheeses themselves.

Is Killing Rivin with Rockers a Cheese Strategy? Debunked

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Culturing in cheese making is the process of adding specific bacteria or molds (cultures) to milk to initiate fermentation. These cultures convert lactose (milk sugar) into lactic acid, which lowers the milk's pH, causing it to curdle and develop flavor, texture, and preservation qualities.

Cultures are essential because they determine the cheese's flavor, texture, and safety. Different cultures produce distinct flavors and control the growth of harmful bacteria. They also play a key role in coagulating milk and creating the desired structure of the cheese.

There are two main types of cultures used: mesophilic (active at moderate temperatures, around 20-40°C) and thermophilic (active at higher temperatures, around 40-55°C). Examples include lactic acid bacteria (e.g., Lactococcus, Lactobacillus) and molds (e.g., Penicillium for blue cheeses). The choice of culture depends on the type of cheese being made.