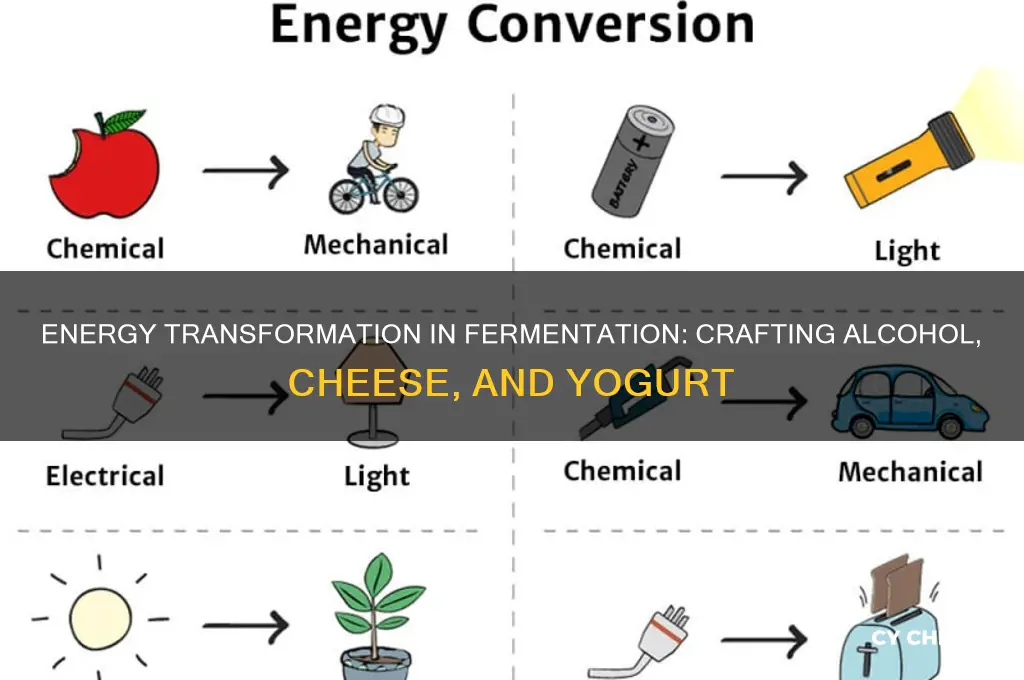

Energy transformation plays a crucial role in the production of alcohol, cheese, and yogurt, as these processes rely on the conversion of energy from one form to another. In alcohol production, such as in brewing and winemaking, the transformation begins with the breakdown of sugars by yeast through fermentation, converting chemical energy stored in carbohydrates into alcohol and carbon dioxide. Similarly, in cheese and yogurt making, microorganisms like bacteria and fungi transform the chemical energy in milk sugars (lactose) into lactic acid, a process that not only preserves the milk but also alters its texture and flavor. These transformations highlight the interplay between biological activity and energy conversion, showcasing how living organisms harness and redirect energy to create diverse food products.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Process in Alcohol | Fermentation of sugars by yeast converts glucose into ethanol and CO₂. |

| Energy Transformation (Alcohol) | Chemical energy in sugars → Chemical energy in ethanol + Heat. |

| Process in Cheese | Fermentation of lactose by bacteria and molds, followed by curdling. |

| Energy Transformation (Cheese) | Chemical energy in lactose → Chemical energy in lactic acid + Heat. |

| Process in Yogurt | Fermentation of lactose by lactic acid bacteria. |

| Energy Transformation (Yogurt) | Chemical energy in lactose → Chemical energy in lactic acid + Heat. |

| Common Factor | Microbial fermentation drives energy transformation in all three products. |

| End Products | Alcohol (ethanol), Cheese (curds + lactic acid), Yogurt (lactic acid). |

| Energy Source | Sugars (glucose/lactose) from raw materials (grains, milk). |

| Byproducts | CO₂ (alcohol), Heat (all processes), Whey (cheese). |

| Applications | Food preservation, flavor enhancement, nutritional value. |

Explore related products

$11.88 $16.99

What You'll Learn

- Fermentation Process: Converts sugars into alcohol, acids, gases via microorganisms like yeast, bacteria

- Alcohol Production: Grains, fruits fermented to produce ethanol in beer, wine, spirits

- Cheese Making: Milk curdled, fermented by bacteria, enzymes to create cheese varieties

- Yogurt Formation: Milk fermented with lactic acid bacteria, thickening into yogurt

- Energy Efficiency: Microbial metabolism transforms chemical energy into food products with minimal waste

Fermentation Process: Converts sugars into alcohol, acids, gases via microorganisms like yeast, bacteria

The fermentation process is a metabolic marvel, a microscopic dance where sugars are transformed into a spectrum of compounds—alcohol, acids, gases—by the tireless work of microorganisms like yeast and bacteria. This ancient practice, honed over millennia, underpins the creation of staples like alcohol, cheese, and yogurt, each a testament to the power of biological energy transformation. At its core, fermentation is a survival mechanism for these microbes, but its byproducts have become integral to human culture and cuisine.

Consider the production of alcohol, a process dominated by yeast. When yeast cells metabolize sugars in the absence of oxygen, they produce ethanol and carbon dioxide through anaerobic respiration. For instance, in winemaking, *Saccharomyces cerevisiae* ferments the glucose in grape juice, converting it into alcohol at a typical efficiency of 51% of the sugar content. This transformation is not just chemical but also energetic: the energy stored in sugar molecules is redistributed, with a portion captured in the alcohol and the rest released as heat and gas. The alcohol content in beverages can be controlled by adjusting fermentation time, temperature (ideally 18–25°C for yeast), and sugar concentration, making this a precise yet accessible process for both industrial and home brewers.

In contrast, the fermentation of dairy into cheese and yogurt relies on lactic acid bacteria, such as *Lactobacillus* and *Streptococcus*. These microbes break down lactose, the sugar in milk, into lactic acid, which coagulates milk proteins and gives these foods their characteristic tang and texture. For yogurt, a starter culture containing *Lactobacillus bulgaricus* and *Streptococcus thermophilus* is added to milk heated to 40–43°C, where it ferments for 4–7 hours. The lactic acid produced lowers the pH, preserving the product and creating a thick, creamy consistency. Cheese fermentation is more complex, often involving additional microbes like *Propionibacterium* in Swiss cheese, which produces carbon dioxide bubbles, or molds in blue cheese, which contribute unique flavors. Here, energy transformation is evident in the shift from lactose to lactic acid, a process that not only preserves milk but also enhances its nutritional profile by increasing bioavailable nutrients like calcium and B vitamins.

Practical applications of fermentation extend beyond food production. Home fermenters can experiment with simple setups: for yogurt, use a yogurt maker or wrap a glass jar in a towel to maintain warmth; for cheese, invest in a pH meter to monitor acidification. However, caution is essential. Contamination by unwanted microbes can spoil batches, so sterilize equipment and maintain hygienic conditions. Temperature control is critical—too high, and microbes die; too low, and fermentation stalls. For alcohol, monitor sugar levels with a hydrometer to track fermentation progress, and always ferment in containers that can withstand gas production to prevent explosions.

In essence, fermentation is a masterclass in energy redirection, where microorganisms convert sugars into products that sustain both themselves and humanity. Whether crafting a batch of kombucha, aging a wheel of cheddar, or brewing beer, understanding this process empowers creators to harness its potential. By manipulating variables like temperature, microbe selection, and substrate composition, one can tailor fermentation outcomes, blending science and art to transform energy into flavor, texture, and tradition. This ancient practice remains a cornerstone of food culture, a reminder that even the smallest organisms can drive profound transformations.

Cheese-Throwing Baby Trend: Unraveling the Bizarre Parenting Ritual

You may want to see also

Alcohol Production: Grains, fruits fermented to produce ethanol in beer, wine, spirits

Fermentation is a metabolic process where microorganisms convert carbohydrates into alcohol and carbon dioxide, a transformation central to alcohol production. Grains like barley, wheat, and rye, as well as fruits such as grapes and apples, serve as the primary substrates. For instance, beer production begins with malted barley, which is soaked, germinated, and dried to activate enzymes that break down starches into fermentable sugars. These sugars are then consumed by yeast, producing ethanol and CO₂, resulting in an alcoholic beverage typically ranging from 4% to 6% ABV (Alcohol By Volume). This process exemplifies how chemical energy stored in carbohydrates is transformed into the kinetic energy of fermentation and the potential energy of alcohol.

Wine production, on the other hand, relies heavily on the natural sugars present in grapes. The process starts with crushing the fruit to release juices, which are then fermented by yeast. Unlike beer, wine fermentation often occurs without the addition of external sugars, yielding alcohol levels between 9% and 16% ABV. The transformation here is more direct, as the sugars in grapes are immediately accessible for fermentation. However, the complexity of flavors in wine arises from secondary transformations, such as the conversion of malic acid to lactic acid during malolactic fermentation, which softens the acidity and adds depth to the final product.

Spirits, including whiskey, vodka, and brandy, involve an additional step: distillation. After initial fermentation, the alcoholic liquid is heated to separate ethanol from water and other compounds, concentrating the alcohol content to 40% ABV or higher. This process requires precise control, as distillation temperatures must remain below ethanol’s boiling point (78.4°C) to avoid unwanted compounds. For example, whiskey is distilled to around 60%–70% ABV before aging in oak barrels, which imparts flavor and color. Here, energy transformation extends beyond fermentation, as heat energy is used to refine and concentrate the alcohol.

Practical considerations in alcohol production include temperature control, yeast selection, and sanitation. Fermentation temperatures must be maintained within specific ranges—typically 18°C to 24°C for beer and 20°C to 30°C for wine—to ensure optimal yeast activity and flavor development. Using specialized yeast strains, such as *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*, can enhance efficiency and flavor profiles. Sanitation is critical to prevent contamination by unwanted microorganisms, which can spoil the product. For homebrewers, sterilizing equipment with a solution of 1 tablespoon of bleach per gallon of water is a simple yet effective method.

The energy transformation in alcohol production is not only biochemical but also ecological. Grains and fruits require significant agricultural energy inputs, from cultivation to harvesting. For example, producing 1 liter of beer consumes approximately 100–200 liters of water, highlighting the resource intensity of the process. However, innovations like spent grain recycling—where leftover grains are used for animal feed or bioenergy—demonstrate how byproducts can be repurposed, reducing waste and improving sustainability. This holistic view of energy transformation underscores the interconnectedness of food, energy, and environmental systems in alcohol production.

Does Aldi Shredded Cheese Contain Cellulose? A Closer Look

You may want to see also

Cheese Making: Milk curdled, fermented by bacteria, enzymes to create cheese varieties

Cheese making is a fascinating process that transforms milk into a diverse array of flavors, textures, and aromas through curdling and fermentation. At its core, this transformation involves the conversion of milk’s chemical energy into the complex structures of cheese, driven by bacteria, enzymes, and precise techniques. Milk, a nutrient-rich liquid, is curdled using rennet or acid, separating it into solid curds and liquid whey. This initial step is not just mechanical but an energy-driven reaction, as enzymes break down proteins and release latent energy stored in molecular bonds. The curds then undergo fermentation, where bacteria metabolize lactose into lactic acid, further altering the energy composition and creating the foundation for cheese’s unique characteristics.

Consider the role of bacteria in this process, a critical energy transformation. Starter cultures, such as *Lactococcus lactis*, are added in specific dosages—typically 1-2% of milk volume—to initiate fermentation. These bacteria consume lactose, a sugar in milk, and produce lactic acid, which lowers the pH and preserves the curds. This metabolic activity is an energy transfer: the chemical energy in lactose is converted into the kinetic energy of bacterial growth and the thermal energy released during fermentation. The type and amount of bacteria used dictate the cheese variety; for example, *Streptococcus thermophilus* and *Lactobacillus bulgaricus* are common in hard cheeses like Cheddar, while *Propionibacterium freudenreichii* creates the distinctive eye holes in Swiss cheese.

Enzymes play an equally vital role, acting as catalysts that accelerate reactions without being consumed. Rennet, an enzyme complex, is added at a rate of 0.02-0.05% of milk weight to coagulate milk proteins into curds. This step is energy-efficient, as enzymes lower the activation energy required for protein bonding, allowing the transformation to occur at milder temperatures (around 30°C or 86°F). Other enzymes, like lipases, break down milk fats, releasing fatty acids that contribute to flavor profiles. For instance, lipase-treated milk produces cheeses with a sharp, tangy taste, such as Pecorino or Feta. The precision in enzyme dosage and timing ensures the desired energy transformation, balancing texture and flavor development.

Practical tips for home cheese makers highlight the importance of controlling energy inputs. Maintaining a consistent temperature during fermentation is crucial; fluctuations can disrupt bacterial activity and enzyme function. For soft cheeses like mozzarella, keep the curds at 35-40°C (95-104°F) during stretching, while harder cheeses require higher temperatures for pressing. Aging cheese is another energy-intensive phase, as humidity and temperature control the slow breakdown of proteins and fats. A cool, humid environment (10-15°C or 50-59°F, 85-90% humidity) is ideal for most varieties, allowing flavors to develop over weeks or months. Monitoring these conditions ensures the energy transformation aligns with the desired outcome, whether a creamy Brie or a crumbly Parmesan.

In essence, cheese making is a masterclass in energy transformation, where milk’s potential energy is reshaped by bacteria, enzymes, and human ingenuity. Each step—curdling, fermenting, aging—relies on precise control of energy inputs to create distinct varieties. Understanding these processes not only deepens appreciation for cheese but also empowers makers to experiment with flavors and textures. From the microbial metabolism of lactose to the catalytic action of enzymes, cheese making exemplifies how energy can be harnessed and redirected to craft a culinary delight.

Chalk and Cheese: Unlikely Pair, Surprising Commonalities Explored

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Yogurt Formation: Milk fermented with lactic acid bacteria, thickening into yogurt

The transformation of milk into yogurt is a fascinating process that hinges on the metabolic activity of lactic acid bacteria (LAB). These microorganisms, primarily *Lactobacillus bulgaricus* and *Streptococcus thermophilus*, convert lactose (milk sugar) into lactic acid through fermentation. This biochemical reaction not only acidifies the milk but also causes it to thicken, resulting in the characteristic texture and tang of yogurt. The energy transformation here is subtle yet profound: the chemical energy stored in lactose is partially converted into lactic acid, with the remainder used by the bacteria for growth and reproduction. This process is a prime example of how microbial activity can alter the physical and chemical properties of a food substrate.

To create yogurt at home, start by heating milk to 180°F (82°C) to denature whey proteins, which will later contribute to the yogurt’s thickness. After cooling the milk to 110°F (43°C), add a starter culture—either store-bought yogurt or a commercial starter—at a ratio of 1 tablespoon per 1 quart (1 liter) of milk. The starter introduces the necessary LAB, which require this specific temperature range to thrive. Incubate the mixture in a warm environment (110°F) for 6–8 hours, during which the bacteria will ferment the lactose. The longer the fermentation, the tangier and thicker the yogurt becomes. For a firmer texture, strain the yogurt through cheesecloth to remove whey, reducing its volume by up to 50%.

While the process appears straightforward, several factors can influence the outcome. Maintaining a consistent temperature is critical; fluctuations below 100°F (38°C) slow fermentation, while higher temperatures can kill the bacteria. Using whole milk yields creamier yogurt, but low-fat milk works too, albeit with a lighter texture. For those with lactose intolerance, the fermentation process reduces lactose content by up to 20%, making yogurt more digestible. Adding flavorings like honey or fruit should occur after fermentation to avoid disrupting bacterial activity.

Comparatively, yogurt formation differs from cheese and alcohol production in its reliance on lactic acid fermentation alone. Cheese involves coagulation of milk proteins with rennet or acid, while alcohol production requires yeast to convert sugars into ethanol. Yogurt’s transformation is uniquely focused on acidification and thickening, making it a milder, more accessible fermentation process. This simplicity, combined with its health benefits—probiotics, calcium, and protein—explains yogurt’s global popularity as a functional food.

In essence, yogurt formation is a delicate balance of microbiology and chemistry, where energy stored in milk is redirected to create a new food product. By understanding the role of LAB and controlling fermentation conditions, anyone can harness this transformation to produce yogurt tailored to their preferences. Whether for culinary experimentation or nutritional benefit, the process exemplifies how energy shifts in food systems can yield both practical and sensory rewards.

Lemon Cheese vs. Lemon Curd: Understanding the Sweet Differences

You may want to see also

Energy Efficiency: Microbial metabolism transforms chemical energy into food products with minimal waste

Microbial metabolism is a powerhouse of efficiency, converting chemical energy into food products like alcohol, cheese, and yogurt with minimal waste. Unlike industrial processes that often generate significant byproducts, microorganisms such as yeast, bacteria, and fungi excel at channeling energy into desired outputs. For instance, in alcoholic fermentation, yeast metabolizes sugars into ethanol and carbon dioxide, with nearly 90% of the sugar’s energy content directed into alcohol production. This precision makes microbial processes inherently sustainable, reducing the environmental footprint of food production.

Consider the production of yogurt, where lactic acid bacteria ferment lactose into lactic acid, thickening milk and creating a tangy flavor. This transformation is remarkably efficient, as the bacteria utilize almost all available lactose, leaving behind a nutrient-dense product with minimal residual sugars. Similarly, in cheese-making, microbial cultures break down milk proteins and fats, converting them into complex flavors and textures while producing only whey as a byproduct, which is often repurposed in other industries. These examples highlight how microbial metabolism maximizes resource use, aligning with principles of circular economy.

To harness this efficiency in home fermentation, start with precise ingredient measurements. For alcohol production, use a hydrometer to measure sugar levels in your fermentable base, ensuring optimal conditions for yeast activity. In yogurt-making, maintain a consistent temperature of 110°F (43°C) during fermentation to encourage bacterial growth without energy waste. For cheese, select specific microbial cultures tailored to the desired variety, as different strains have varying metabolic efficiencies. These small steps amplify the inherent energy efficiency of microbial processes.

While microbial metabolism is inherently efficient, external factors can disrupt its performance. Contamination by unwanted microorganisms or fluctuations in temperature can divert energy into unwanted byproducts or slow down fermentation. To mitigate this, sterilize equipment using a 1:10 bleach solution or boiling water, and monitor fermentation environments with digital thermometers. Additionally, avoid overloading the substrate with excessive sugars or proteins, as this can overwhelm the microbes and lead to incomplete transformations. By optimizing conditions, you can ensure that microbial metabolism operates at peak efficiency, delivering high-quality food products with minimal waste.

The takeaway is clear: microbial metabolism offers a blueprint for energy-efficient food production. By understanding and supporting these processes, we can create sustainable, resource-conscious systems that minimize waste and maximize output. Whether you’re brewing beer, culturing yogurt, or crafting cheese, embracing microbial efficiency not only yields delicious results but also contributes to a more sustainable food future.

Low-Sodium Cheese Options: Discover the Healthiest Choices for Your Diet

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Energy transformation refers to the process of converting one form of energy into another. In the production of alcohol, cheese, and yogurt, biological and chemical processes transform the energy stored in raw materials (like sugars and proteins) into new products, often involving microbial activity and heat.

During alcohol fermentation, yeast converts sugars (such as glucose) into ethanol and carbon dioxide. This process transforms the chemical energy stored in sugars into the chemical energy of alcohol, with heat being released as a byproduct of the metabolic activity.

In cheese and yogurt production, bacteria transform lactose (milk sugar) into lactic acid through fermentation. This process converts the chemical energy in lactose into the energy stored in lactic acid, which also causes milk proteins to coagulate. Heat is often applied to further transform the structure and energy distribution in the final product.