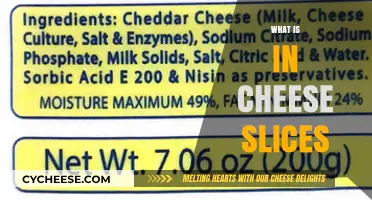

Cheese food, often found in processed or packaged products, is a blend of natural cheese and additional ingredients designed to enhance texture, shelf life, and flavor. Unlike traditional cheese, which is primarily made from milk, rennet, and cultures, cheese food typically includes emulsifiers, stabilizers, preservatives, and sometimes artificial additives. Common ingredients in cheese food products are whey, milkfat, sodium phosphate, and salt, along with coloring agents to mimic the appearance of natural cheese. While it offers convenience and versatility, cheese food often lacks the complexity and nutritional profile of real cheese, making it a subject of debate among food enthusiasts and health-conscious consumers. Understanding its composition is key to making informed choices about its role in one's diet.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Primary Ingredient | Milk (cow, goat, sheep, or other mammals) |

| Fat Content | Varies (e.g., low-fat, full-fat, depending on type) |

| Protein Content | High (typically 20-30 grams per 100 grams) |

| Calcium | Rich source (e.g., ~700 mg per 100 grams in cheddar) |

| Vitamins | Vitamin A, B12, riboflavin (B2), and phosphorus |

| Cholesterol | Present (e.g., ~100 mg per 100 grams in cheddar) |

| Sodium | High (e.g., ~600 mg per 100 grams in cheddar) |

| Carbohydrates | Low (typically <5 grams per 100 grams) |

| Lactose | Varies (hard cheeses have less lactose than soft cheeses) |

| Additives | May include salt, enzymes, cultures, preservatives, and colorings |

| Texture | Ranges from soft (e.g., Brie) to hard (e.g., Parmesan) |

| Flavor | Diverse (mild, sharp, nutty, tangy, depending on type and aging) |

| Aging Process | Varies (from a few weeks to several years) |

| Shelf Life | Depends on type (e.g., fresh cheeses: short; aged cheeses: longer) |

| Allergens | Contains milk (potential allergen for lactose intolerant or dairy allergic individuals) |

| Processed Cheese Food | Contains cheese, emulsifiers, stabilizers, and additional ingredients |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Milk Sources: Cheese is made from cow, goat, sheep, or buffalo milk, each adding unique flavors

- Coagulation Process: Rennet or acids curdle milk, separating solids (curds) from liquids (whey)

- Aging & Ripening: Time and bacteria transform texture and taste, from mild to sharp

- Common Additives: Salt, enzymes, and cultures enhance flavor, preservation, and consistency in cheese

- Nutritional Content: Cheese contains protein, calcium, fat, and vitamins like B12 and A

Milk Sources: Cheese is made from cow, goat, sheep, or buffalo milk, each adding unique flavors

Cheese, a culinary chameleon, owes its diverse flavors and textures to the milk from which it's crafted. The choice of milk—cow, goat, sheep, or buffalo—isn't merely a detail; it's the foundation of the cheese's character. Each milk type brings its own unique profile, influenced by the animal's diet, breed, and even the region where it's raised. For instance, cow's milk, the most commonly used, tends to produce cheeses with a mild, buttery flavor, as seen in classics like Cheddar and Mozzarella. However, the fat and protein content in cow's milk can vary, affecting the cheese's texture and melting properties.

To truly appreciate the impact of milk source, consider the following experiment: compare a young goat cheese (chèvre) to a sheep's milk cheese like Manchego. The goat cheese will likely have a tangy, slightly acidic taste with a creamy texture, ideal for spreading on crusty bread. In contrast, Manchego offers a nuttier, richer flavor with a firmer bite, perfect for pairing with bold wines. This comparison highlights how the milk's inherent qualities are amplified during the cheesemaking process.

When selecting cheese, understanding the milk source can guide your choice based on desired flavor and texture. For instance, buffalo milk, with its higher fat content, creates cheeses like Mozzarella di Bufala, known for their luxurious creaminess and delicate, milky flavor. This makes it a premium choice for dishes like Caprese salad, where the cheese's texture and taste are center stage. Sheep's milk, on the other hand, is ideal for aged cheeses due to its high protein and fat content, resulting in robust, complex flavors as seen in Pecorino Romano.

For home cheesemakers or enthusiasts, experimenting with different milk sources can be a rewarding way to explore cheese diversity. Start with a simple recipe like ricotta, which can be made from any of these milks, and note the subtle differences in taste and texture. Cow's milk ricotta will be milder and more versatile, while goat's milk ricotta will have a distinct tang, adding a unique twist to desserts or pasta dishes. Sheep's milk ricotta, though less common, offers a richer, more decadent option.

Incorporating cheeses from various milk sources into your diet not only broadens your culinary horizons but also supports diverse agricultural practices. Each milk type reflects the terroir and traditions of its origin, making cheese a delicious way to explore global cultures. Whether you're a cheese connoisseur or a casual enthusiast, paying attention to the milk source can deepen your appreciation for this ancient food, turning every bite into a journey of discovery.

Is Mascarpone Cheese Tart? Unveiling Its Unique Flavor Profile

You may want to see also

Coagulation Process: Rennet or acids curdle milk, separating solids (curds) from liquids (whey)

The transformation of milk into cheese begins with coagulation, a process that separates milk into solid curds and liquid whey. This fundamental step is achieved through the use of rennet or acids, each bringing distinct characteristics to the final product. Rennet, derived from the stomach lining of ruminant animals, contains chymosin, an enzyme that efficiently clots milk proteins at a typical dosage of 1:10,000 (1 drop of rennet per 10 liters of milk). Acids, such as citric acid or vinegar, work by lowering the milk’s pH, causing proteins to precipitate out. While rennet produces a cleaner break and is ideal for hard cheeses like cheddar, acids are often used in softer, fresher cheeses like ricotta, where a quicker, less precise curdling is acceptable.

Understanding the coagulation process requires a closer look at the science behind it. When rennet is added to milk, chymosin cleaves kappa-casein, a protein that stabilizes micelles, allowing them to aggregate into curds. This reaction is temperature-sensitive, typically occurring between 30°C and 35°C (86°F to 95°F). Acids, on the other hand, denature milk proteins directly by disrupting their structure, a process that works best in warmer milk (around 55°C or 131°F). The choice between rennet and acids depends on the desired texture, flavor, and aging potential of the cheese. For instance, rennet-coagulated cheeses tend to have a smoother, more elastic texture, while acid-coagulated cheeses are often crumbly and mild.

For home cheesemakers, mastering coagulation is both an art and a science. Beginners should start with acid-coagulated cheeses like paneer or queso blanco, as they require fewer variables to control. Simply heat milk to 80°C (176°F), add 2–3 tablespoons of white vinegar or lemon juice per gallon of milk, and stir gently until curds form. For rennet-based cheeses, precision is key. Dissolve 1/4 teaspoon of liquid rennet in 1/4 cup of cool, non-chlorinated water, then stir into 4 gallons of milk at 30°C (86°F). Allow the mixture to set undisturbed for 12–24 hours, depending on the recipe. Always use food-grade thermometers and sanitized equipment to ensure consistency and safety.

Comparing the two methods highlights their unique strengths and limitations. Rennet coagulation is slower but yields a more cohesive curd, essential for aged cheeses that require pressing and molding. Acid coagulation is faster and simpler, making it ideal for fresh cheeses consumed within days. However, acids can impart a tangy flavor, which may not suit all palates. For those experimenting with both methods, consider blending them: a small amount of acid can speed up rennet coagulation, a technique often used in artisanal cheesemaking. Ultimately, the choice of coagulant shapes not only the cheese’s structure but also its identity, from the sharp bite of cheddar to the delicate crumble of ricotta.

In practice, the coagulation process is a gateway to creativity in cheesemaking. Experimenting with different coagulants, temperatures, and milk types (cow, goat, sheep) allows for endless variations. For instance, using goat’s milk with rennet produces a tangier, firmer cheese compared to cow’s milk. Adding calcium chloride (1/4 teaspoon per gallon of milk) can improve curd formation in pasteurized milk, which often lacks sufficient calcium. Whether you’re crafting a complex Gruyère or a simple queso fresco, understanding coagulation empowers you to control the outcome, turning humble milk into a culinary masterpiece.

Understanding Rennet: Which Cheeses Contain This Coagulant and Why

You may want to see also

Aging & Ripening: Time and bacteria transform texture and taste, from mild to sharp

Cheese, in its myriad forms, owes much of its complexity to the aging and ripening process, a delicate dance between time and bacteria. This transformation is not merely a waiting game but a precise science that dictates texture, flavor, and aroma. Consider the difference between a young, creamy Brie and a mature, crumbly Parmesan—both start as milk, yet their journeys diverge dramatically. The key players here are microorganisms, primarily lactic acid bacteria and molds, which break down proteins and fats, releasing compounds that deepen and sharpen the cheese’s character. Without this process, cheese would remain a bland, uniform product, lacking the nuanced profiles that enthusiasts cherish.

To understand ripening, imagine cheese as a canvas where bacteria are the artists. During aging, these microbes metabolize lactose and proteins, producing acids, alcohols, and esters that contribute to flavor development. For instance, in Cheddar, the longer the aging, the more pronounced the sharpness, as bacteria break down lactose into lactic acid, intensifying the tang. Similarly, in blue cheeses like Roquefort, Penicillium molds create veins that introduce a pungent, earthy note. Temperature and humidity play critical roles here—a cool, moist environment slows ripening, allowing flavors to develop gradually, while warmer conditions accelerate the process. For home enthusiasts, maintaining a consistent 50-55°F (10-13°C) and 85-90% humidity in a dedicated fridge or aging box can replicate ideal conditions.

The texture of cheese also undergoes a remarkable evolution during aging. Fresh cheeses like mozzarella retain their moisture and softness due to minimal ripening, but as cheese ages, moisture evaporates, and proteins tighten, leading to a firmer, sometimes crumbly texture. Take Gruyère, for example—young versions are supple and slightly elastic, while aged wheels become hard and granular, ideal for grating. This transformation is not accidental; it’s a result of enzymes breaking down casein (milk protein) and fat globules, creating a denser structure. For those experimenting at home, monitor moisture loss by weighing the cheese weekly—a 20-30% reduction over several months is typical for hard cheeses.

Practical tips for appreciating aged cheeses abound. Pairing is an art: sharp, aged cheeses like aged Gouda or Manchego complement sweet accompaniments such as honey or dried fruit, balancing their intensity. When cooking, use younger, milder cheeses for melting (think grilled cheese with young Cheddar) and reserve aged varieties for grating or shaving over dishes to add a flavor punch without overwhelming the palate. Storage matters too—wrap aged cheeses in wax or parchment paper to allow breathability, and avoid plastic, which traps moisture and promotes spoilage. For optimal flavor, let cheese sit at room temperature for 30 minutes before serving, allowing its aromatic compounds to fully express.

In essence, aging and ripening are the alchemy that turns milk into a culinary masterpiece. By understanding the role of time, bacteria, and environmental factors, one can better appreciate—and even replicate—the magic behind cheese’s transformation. Whether you’re a casual consumer or a budding cheesemaker, recognizing how these processes shape texture and taste elevates every bite from mere sustenance to an experience. After all, in the world of cheese, patience isn’t just a virtue—it’s the secret ingredient.

Is String Cheese Acidic? Unraveling the pH Mystery of This Snack

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Common Additives: Salt, enzymes, and cultures enhance flavor, preservation, and consistency in cheese

Salt, enzymes, and cultures are the unsung heroes of cheese, working behind the scenes to transform milk into a diverse array of flavors, textures, and shelf lives. Salt, for instance, is more than just a flavor enhancer. It acts as a preservative by drawing moisture out of the cheese, creating an environment hostile to bacteria that cause spoilage. In hard cheeses like Parmesan, salt is added at a rate of about 2-3% of the milk weight, while softer cheeses like mozzarella use less, around 0.5-1%, to maintain their pliable texture. Too much salt can overpower the delicate flavors, while too little can lead to a shorter shelf life and potential bacterial growth.

Enzymes, particularly rennet and its microbial alternatives, play a pivotal role in curdling milk, a critical step in cheese making. Rennet contains chymosin, an enzyme that coagulates milk proteins into a solid mass (curds) and liquid (whey). For those avoiding animal products, microbial enzymes derived from fungi or bacteria offer a vegetarian-friendly solution. The dosage of rennet is precise: typically 0.02-0.05% of the milk volume, depending on the type of cheese. Overuse can result in a bitter taste, while underuse may prevent proper curdling. Understanding this balance is key for both artisanal and industrial cheese production.

Cultures, often a blend of bacteria and sometimes molds, are the architects of cheese flavor and texture. Lactic acid bacteria, for example, ferment lactose into lactic acid, lowering the pH and contributing to the tangy taste of cheeses like cheddar. In blue cheeses, Penicillium molds create veins and a distinctive pungency. Starter cultures are added at a rate of 0.5-2% of the milk volume, depending on the desired outcome. The choice of culture determines whether a cheese will be mild or sharp, crumbly or creamy. For home cheese makers, selecting the right culture and maintaining proper temperature (typically 72-100°F) during fermentation is crucial for success.

The interplay of salt, enzymes, and cultures is a delicate dance, each component influencing the others. Salt not only preserves but also slows down the activity of enzymes and cultures, allowing for controlled ripening. Enzymes set the stage for cultures to work their magic, breaking down proteins and fats into complex flavor compounds. Cultures, in turn, interact with salt to create the unique characteristics of each cheese variety. For instance, in aged cheeses like Gruyère, the combination of high salt content and specific cultures results in a hard, nutty flavor profile. Mastering these additives is essential for crafting cheese that is both delicious and safe to consume.

Practical tips for cheese enthusiasts: when making cheese at home, always measure salt and enzymes precisely—a kitchen scale is your best tool. Experiment with different cultures to explore flavor variations, but start with reliable brands for consistent results. Store cheese properly to maximize the effects of these additives: wrap hard cheeses in wax paper to breathe, and keep softer cheeses in airtight containers to prevent moisture loss. Understanding these common additives not only deepens your appreciation for cheese but also empowers you to create or select the perfect cheese for any occasion.

Is Cheese an Animal Protein Source? Uncovering Dairy's Nutritional Truth

You may want to see also

Nutritional Content: Cheese contains protein, calcium, fat, and vitamins like B12 and A

Cheese, a staple in diets worldwide, is more than just a flavorful addition to meals—it’s a nutrient-dense food that offers a unique blend of essential components. At its core, cheese is a concentrated source of protein, providing approximately 7 grams per ounce, which supports muscle repair and growth. This makes it an excellent choice for athletes, growing children, and anyone looking to meet their daily protein needs without relying solely on meat.

Beyond protein, cheese is a standout source of calcium, delivering around 200 milligrams per ounce. This mineral is critical for bone health, particularly in children, adolescents, and older adults who are at higher risk of osteoporosis. A single serving of cheese can contribute significantly to the recommended daily intake of 1,000–1,300 milligrams, depending on age and life stage. Pairing cheese with vitamin D-rich foods like fortified milk or sunlight exposure enhances calcium absorption, maximizing its benefits.

While cheese is celebrated for its nutritional strengths, its fat content often sparks debate. A one-ounce serving typically contains 6–9 grams of fat, including saturated fat. However, emerging research suggests that the relationship between dairy fat and health is more nuanced than previously thought. For instance, full-fat cheese may promote satiety, reducing overall calorie intake, and some studies link dairy fat to improved lipid profiles. Moderation is key—opt for portion control or choose lower-fat varieties like part-skim mozzarella for a balanced approach.

Vitamins B12 and A are two lesser-known but vital nutrients found in cheese. Vitamin B12, essential for nerve function and DNA synthesis, is abundant in cheese, with one ounce providing up to 10% of the daily value. This makes cheese a valuable option for vegetarians and vegans who may struggle to obtain B12 from plant-based sources. Vitamin A, crucial for immune function and vision, is also present, particularly in orange-hued cheeses like cheddar, which derive their color from carotene-rich milk.

Incorporating cheese into a balanced diet requires mindful choices. For those monitoring sodium intake, opt for fresh cheeses like ricotta or goat cheese, which contain less salt than aged varieties. Pairing cheese with fiber-rich foods like whole-grain crackers or fresh vegetables can offset its higher fat content while creating a satisfying snack. Ultimately, cheese’s nutritional profile—rich in protein, calcium, and key vitamins—makes it a versatile and valuable addition to meals, provided it’s enjoyed in moderation and tailored to individual dietary needs.

Peanut Butter vs. Cheese: Which is Better for Cholesterol?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Cheese food is typically made from a blend of natural cheese, whey, milk, emulsifiers, and preservatives. It often contains less cheese than traditional cheese products and may include added ingredients like salt, flavorings, and stabilizers.

No, cheese food is not the same as real cheese. It is a processed product that contains a mixture of cheese and other ingredients, whereas real cheese is made primarily from milk, cultures, and rennet, with minimal additives.

Cheese food is commonly used as a spread, in sandwiches, or as a topping for snacks like crackers or nachos. Its smooth, meltable texture makes it versatile for quick and convenient applications.

Cheese food often contains higher levels of sodium, additives, and preservatives compared to natural cheese. Consuming it in excess may contribute to health issues like high blood pressure or increased calorie intake. It’s best enjoyed in moderation.