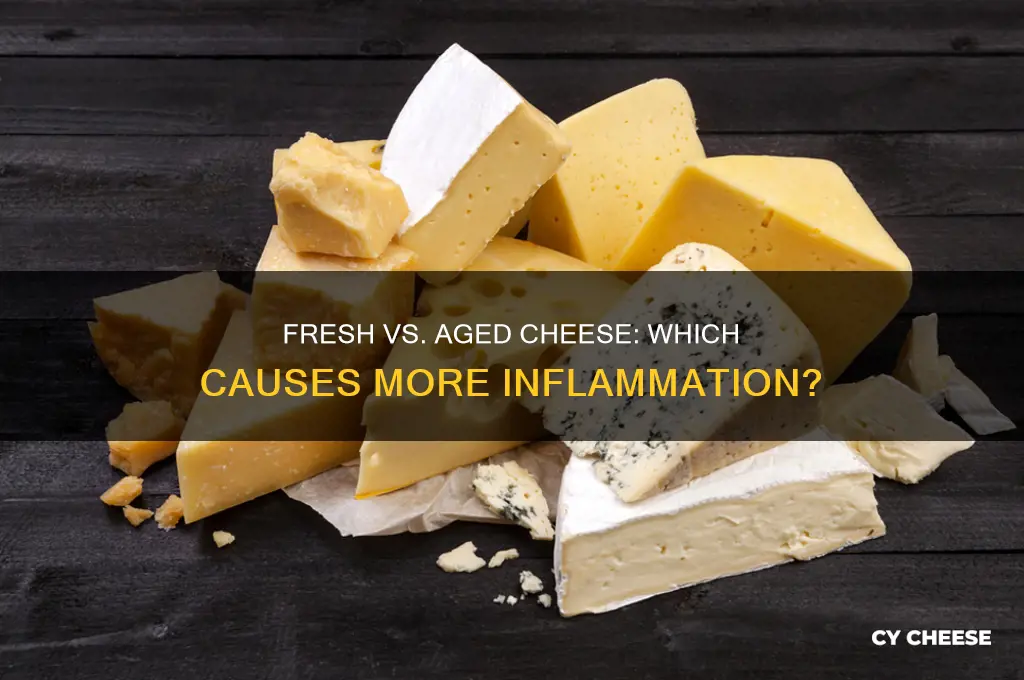

The question of whether fresh cheese or aged cheese is more inflammatory is a nuanced one, as it depends on various factors including individual tolerance, the specific type of cheese, and the aging process. Fresh cheeses, such as mozzarella or ricotta, typically contain higher levels of lactose and moisture, which can trigger inflammation in individuals with lactose intolerance or dairy sensitivities. On the other hand, aged cheeses, like cheddar or Parmesan, have lower lactose content due to the fermentation and aging process, which breaks down lactose and reduces its inflammatory potential for some people. However, aged cheeses often contain higher levels of histamine and advanced glycation end products (AGEs), which can exacerbate inflammation in those with histamine intolerance or certain chronic conditions. Ultimately, the inflammatory impact of fresh versus aged cheese varies based on personal health factors and dietary sensitivities.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Lactose Content | Fresh cheese generally contains more lactose, which can be inflammatory for lactose-intolerant individuals. Aged cheese has lower lactose due to fermentation. |

| Protein Composition | Aged cheese has higher levels of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) and casein, which may trigger inflammation in some people. Fresh cheese has fewer AGEs. |

| Fat Content | Both can be high in saturated fats, but aged cheese often has a higher fat concentration, which may contribute to inflammation in excess. |

| Histamine Levels | Aged cheese contains higher histamine levels due to fermentation, which can cause inflammatory responses in histamine-sensitive individuals. Fresh cheese has lower histamine. |

| Additives/Preservatives | Fresh cheese typically has fewer additives, while aged cheese may contain more preservatives or molds, potentially increasing inflammation in sensitive individuals. |

| Digestibility | Fresh cheese is generally easier to digest due to lower lactose and histamine, reducing inflammatory potential for most people. |

| Overall Inflammatory Impact | Aged cheese is more likely to be inflammatory due to higher AGEs, histamine, and casein, while fresh cheese is milder for most individuals. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Lactose Content Comparison: Fresh cheese has more lactose, potentially triggering inflammation in lactose-intolerant individuals

- Protein Structure Changes: Aging breaks down proteins, reducing inflammatory potential in aged cheese

- Fat Composition Impact: Aged cheese has higher saturated fats, which may promote inflammation in some

- Histamine Levels: Aged cheese contains more histamine, a known inflammatory compound for sensitive people

- Additive Differences: Fresh cheese often lacks additives, while aged cheese may include inflammatory preservatives

Lactose Content Comparison: Fresh cheese has more lactose, potentially triggering inflammation in lactose-intolerant individuals

Fresh cheese, such as mozzarella or ricotta, retains significantly more lactose compared to aged varieties like cheddar or Parmesan. This is because the aging process breaks down lactose into simpler sugars, reducing its overall content. For lactose-intolerant individuals, this distinction is critical. Consuming even small amounts of lactose can trigger digestive discomfort, bloating, and inflammation. A single ounce of fresh mozzarella contains roughly 0.5–1 gram of lactose, while the same portion of aged cheddar has less than 0.1 gram. This disparity highlights why fresh cheese is more likely to exacerbate inflammatory responses in sensitive individuals.

Understanding lactose’s role in inflammation requires a closer look at how the body processes it. Lactose intolerance occurs when the enzyme lactase, which breaks down lactose in the small intestine, is insufficient. Undigested lactose ferments in the gut, producing gas and triggering an immune response that can lead to inflammation. For those with severe intolerance, even trace amounts matter. Aged cheeses, with their minimal lactose content, often become a safer alternative. However, portion control remains essential, as cumulative intake can still cause issues.

Practical tips can help lactose-intolerant individuals navigate cheese consumption. Start by limiting fresh cheese intake to no more than 1–2 ounces per serving, monitoring symptoms closely. Pairing fresh cheese with lactase enzymes or opting for lactose-free versions can mitigate reactions. Aged cheeses, while generally safer, should still be consumed mindfully, especially in larger quantities. For instance, a 2-ounce serving of aged Parmesan, though low in lactose, is high in fat and calories, which could contribute to other health concerns if overindulged.

Comparatively, the inflammatory potential of fresh versus aged cheese hinges on lactose content and individual tolerance. While aged cheese is a better option for most lactose-intolerant people, it’s not a one-size-fits-all solution. Factors like overall diet, gut health, and the presence of other food sensitivities play a role. For instance, someone with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) might still react to aged cheese due to its high histamine content. Tailoring choices to personal tolerance levels and consulting a dietitian can provide a more nuanced approach.

In conclusion, the lactose content in fresh cheese makes it a more inflammatory option for lactose-intolerant individuals compared to aged varieties. By understanding this difference and adopting practical strategies, such as portion control and enzyme supplementation, those with sensitivities can enjoy cheese without triggering discomfort. Aged cheese, while generally safer, should still be consumed thoughtfully, considering individual health factors. This knowledge empowers informed dietary choices, balancing enjoyment with well-being.

Is American Cheese a Blend of Two Cheeses? Uncovering the Truth

You may want to see also

Protein Structure Changes: Aging breaks down proteins, reducing inflammatory potential in aged cheese

Aging cheese is a transformative process that alters its nutritional profile, particularly the structure of its proteins. Fresh cheese, such as mozzarella or ricotta, contains proteins in their native, intact form. These proteins can sometimes trigger inflammatory responses in sensitive individuals, as the immune system may recognize them as foreign. In contrast, aged cheeses like cheddar or Parmesan undergo proteolysis, where enzymes break down complex proteins into smaller peptides and amino acids. This breakdown reduces the protein’s ability to provoke an inflammatory reaction, making aged cheese generally less inflammatory than its fresh counterparts.

Consider the mechanism behind this transformation. During aging, enzymes like rennet and bacteria-produced proteases act on the cheese’s protein matrix, cleaving large proteins into smaller fragments. These fragments are less likely to bind to immune receptors that trigger inflammation. For example, casein, a major protein in milk, is hydrolyzed into bioactive peptides with anti-inflammatory properties. Studies show that these peptides can modulate immune responses, reducing markers of inflammation such as cytokines. This is why individuals with mild lactose intolerance or dairy sensitivities often tolerate aged cheeses better than fresh ones.

Practical implications of this protein breakdown are worth noting. For those monitoring inflammation through diet, opting for aged cheeses can be a strategic choice. A 30-gram serving of aged cheddar, for instance, provides a lower inflammatory load compared to the same amount of fresh cheese. However, moderation is key, as aged cheeses are often higher in sodium and fat. Pairing aged cheese with anti-inflammatory foods like nuts, berries, or leafy greens can further enhance its benefits. For optimal results, choose cheeses aged at least 6 months, as longer aging correlates with greater protein breakdown and reduced inflammatory potential.

To incorporate this knowledge into daily habits, start by reading labels to identify aging durations. Cheeses labeled as "aged," "sharp," or "extra mature" are ideal. Experiment with varieties like Gruyère, Gouda, or aged goat cheese to diversify your intake. If you’re new to aged cheeses, begin with milder options and gradually explore stronger flavors. For those with specific health concerns, consult a dietitian to tailor cheese choices to individual needs. By understanding the science of protein structure changes, you can make informed decisions that align with your dietary goals while enjoying the rich flavors of aged cheese.

Halloumi vs. Queso Blanco: Are These Cheeses Truly Interchangeable?

You may want to see also

Fat Composition Impact: Aged cheese has higher saturated fats, which may promote inflammation in some

Aged cheeses, revered for their complex flavors and textures, undergo a transformation that concentrates their fat content. This process results in a higher proportion of saturated fats compared to fresh cheeses. Saturated fats, particularly when consumed in excess, have been linked to increased inflammation in certain individuals. For example, a 30g serving of aged cheddar contains approximately 5g of saturated fat, while the same portion of fresh mozzarella contains around 2g. This disparity highlights the potential inflammatory impact of aged cheese, especially for those with sensitivities or pre-existing conditions.

Consider the mechanism behind this effect: saturated fats can trigger the release of pro-inflammatory molecules in the body, such as cytokines. Over time, chronic inflammation may contribute to conditions like cardiovascular disease or arthritis. A study published in the *Journal of Nutrition* found that diets high in saturated fats were associated with elevated inflammatory markers in participants. However, the response to saturated fats varies; some individuals may metabolize them differently, reducing their inflammatory risk. Understanding your body’s reaction to these fats is crucial for making informed dietary choices.

Practical steps can mitigate the inflammatory potential of aged cheese. First, moderation is key. Limiting aged cheese intake to 1–2 servings per week can balance enjoyment with health considerations. Pairing aged cheese with anti-inflammatory foods, such as nuts, berries, or leafy greens, can also offset its effects. For instance, a small portion of aged gouda alongside a handful of almonds provides a satisfying snack while introducing healthy fats and antioxidants. Additionally, opting for lower-fat aged cheeses or blending them with fresh varieties can reduce saturated fat intake without sacrificing flavor.

Age and health status play a significant role in how saturated fats from aged cheese affect inflammation. Younger, healthy individuals may tolerate higher saturated fat intake without noticeable inflammatory responses. However, older adults or those with metabolic conditions like diabetes or obesity may experience heightened sensitivity. For these groups, substituting aged cheese with fresh alternatives or plant-based options could be beneficial. Consulting a healthcare provider or dietitian can provide personalized guidance based on individual health profiles.

In conclusion, while aged cheese offers unparalleled culinary richness, its higher saturated fat content warrants attention for those concerned about inflammation. By understanding the science, adopting practical strategies, and considering individual health factors, it’s possible to enjoy aged cheese while minimizing its inflammatory potential. This nuanced approach allows for a balanced diet that prioritizes both taste and well-being.

Creative Ways to Use Leftover Cheesecake Filling: Delicious Ideas

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Histamine Levels: Aged cheese contains more histamine, a known inflammatory compound for sensitive people

Aged cheeses, such as cheddar, Parmesan, and blue cheese, undergo a fermentation process that increases their histamine content. Histamine is a compound naturally produced by bacteria during aging, and it’s a double-edged sword: while it contributes to the rich, complex flavors of aged cheeses, it can trigger inflammation in sensitive individuals. For those with histamine intolerance or conditions like mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS), even small amounts of histamine can lead to symptoms like headaches, hives, digestive issues, or nasal congestion. Fresh cheeses, such as mozzarella or ricotta, bypass this issue because they are not aged, making them a safer option for histamine-sensitive individuals.

Consider this: a 1-ounce serving of aged cheddar can contain up to 100–200 mg of histamine, while the same amount of fresh mozzarella typically contains less than 1 mg. For someone with histamine intolerance, the difference is significant. The threshold for histamine sensitivity varies, but many individuals begin experiencing symptoms after consuming 50–100 mg in a single meal. If you’re unsure of your tolerance, start by tracking your symptoms after consuming aged cheeses and compare them to how you feel after eating fresh varieties. Keeping a food diary can help identify patterns and pinpoint histamine as the culprit.

For those who love cheese but struggle with histamine sensitivity, the solution isn’t necessarily to eliminate cheese entirely. Instead, focus on portion control and frequency. Limit aged cheese consumption to small servings (e.g., 1 ounce or less) and pair it with low-histamine foods like fresh vegetables or grains to dilute its impact. Alternatively, opt for fresh cheeses as your go-to choice, as they provide the creamy texture and flavor without the histamine load. If you’re dining out, ask about the types of cheese used in dishes and choose options like goat cheese or feta, which are lower in histamine compared to aged varieties.

It’s also worth noting that not all aged cheeses are created equal. Harder, longer-aged cheeses like Parmesan tend to have higher histamine levels than semi-soft varieties like young Gouda. If you’re experimenting with aged cheeses, start with milder, shorter-aged options and monitor your body’s response. Additionally, pairing cheese with anti-inflammatory foods like berries, turmeric, or leafy greens can help offset potential inflammation. For those with severe histamine intolerance, consulting a dietitian or allergist can provide personalized guidance on managing symptoms while still enjoying dairy.

Finally, while histamine is a key concern, it’s not the only factor in cheese’s inflammatory potential. Aged cheeses are also higher in tyramine, another compound that can trigger migraines or blood pressure fluctuations in sensitive individuals. However, histamine remains the primary inflammatory concern for most. By understanding the histamine content of different cheeses and making informed choices, you can savor cheese without compromising your health. Fresh cheeses offer a histamine-friendly alternative, but for those who can’t resist aged varieties, moderation and mindful pairing are key.

Carb Count: Ham and Cheese Sandwich Carbohydrate Breakdown

You may want to see also

Additive Differences: Fresh cheese often lacks additives, while aged cheese may include inflammatory preservatives

Fresh cheese, such as mozzarella or ricotta, is typically consumed within days of production, leaving little time for additives to enter the equation. This minimal processing preserves the cheese's natural state, free from preservatives, artificial colors, or flavor enhancers. In contrast, aged cheeses like cheddar or Parmesan undergo a lengthy maturation process, often requiring additives to prevent spoilage and enhance shelf life. These additives can include natamycin, a common antifungal agent, or synthetic preservatives like sorbic acid. While these substances serve a functional purpose, they introduce potential inflammatory triggers for sensitive individuals.

Consider the case of natamycin, a preservative widely used in aged cheeses. Approved by the FDA, natamycin is considered safe for consumption in regulated amounts (typically 20 ppm or less). However, studies suggest that even trace amounts of this additive can provoke inflammatory responses in individuals with pre-existing conditions like irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) or Crohn’s disease. For instance, a 2020 study published in the *Journal of Food Science* found that natamycin exposure exacerbated gut inflammation in mice models, highlighting the need for caution among vulnerable populations.

To minimize inflammatory risks, prioritize fresh cheeses or opt for aged varieties labeled "additive-free" or "naturally preserved." Artisanal cheesemakers often rely on traditional methods, such as wax coating or brine curing, to extend shelf life without synthetic additives. When purchasing aged cheese, scrutinize labels for E-numbers (e.g., E235 for natamycin) or generic terms like "preservatives." If you’re unsure, consult a cheesemonger or choose organic options, which adhere to stricter additive regulations.

For those with known sensitivities, a practical tip is to monitor portion sizes. Limiting aged cheese intake to 30–50 grams per serving can reduce additive exposure while still allowing enjoyment of its flavor profile. Pairing aged cheese with anti-inflammatory foods, such as walnuts or olive oil, may also mitigate potential adverse effects. Ultimately, understanding the additive differences between fresh and aged cheeses empowers consumers to make informed choices tailored to their health needs.

Locatelli Romano Cheese: Sheep or Cow's Milk? Unraveling the Mystery

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Aged cheese is generally considered more inflammatory due to its higher levels of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) and histamine, which can trigger inflammatory responses in some individuals.

Aged cheeses undergo longer fermentation and aging processes, which increase their histamine and AGEs content. These compounds can stimulate inflammation in sensitive individuals.

Fresh cheeses are less likely to cause inflammation for most people, but individual tolerance varies. Some may still react to lactose or other components in fresh cheese.

Fresh cheese is generally a better option for those with inflammatory conditions, but it’s best to monitor personal reactions, as dairy can still trigger inflammation in some cases.

Opt for fresh cheeses like mozzarella or ricotta, consume cheese in moderation, and pair it with anti-inflammatory foods like vegetables or healthy fats to minimize potential inflammatory effects.