The exterior of a cheese wheel, often referred to as the rind, is a crucial yet frequently overlooked component that plays a significant role in the cheese's development, protection, and flavor profile. Depending on the type of cheese, the rind can vary widely in texture, color, and composition, ranging from soft and bloomy to hard and wax-coated. For example, Brie features a velvety white mold rind, while Parmesan boasts a hard, natural rind that forms during aging. Some rinds are edible, contributing to the overall taste and texture, while others are purely protective and meant to be removed before consumption. Understanding the rind not only enhances appreciation for the cheese-making process but also guides proper handling and serving techniques.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Rind Type | Natural, Waxed, Cloth-bound, Ash-coated, Brined, Mold-ripened |

| Texture | Smooth, Rough, Wrinkled, Sticky, Dry, Hard |

| Color | White, Yellow, Orange, Brown, Gray, Blue-green (from mold) |

| Mold Presence | Penicillium, Geotrichum, Brevibacterium (for smear-ripened cheeses) |

| Coating Material | Wax, Plastic, Cloth, Ash, Oil, Paper |

| Markings | Brand logos, Production dates, Batch numbers, Country of origin |

| Aroma | Mild, Pungent, Earthy, Ammonia-like (in strong cheeses) |

| Edibility | Edible (e.g., natural rinds) or Non-edible (e.g., waxed rinds) |

| Thickness | Varies from thin (e.g., Brie) to thick (e.g., Parmesan) |

| Purpose | Protection from moisture loss, Mold development, Flavor enhancement |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Natural Rind: Outer layer, often mold-ripened, protecting cheese, influencing flavor, texture, and aging process

- Wax Coating: Applied to preserve moisture, prevent mold, and extend shelf life of cheese

- Ash Layer: Thin coating of edible ash, adding earthy flavor and unique appearance to cheese

- Brined Surface: Salt-cured exterior, creating a firm texture and tangy taste, common in feta

- Artificial Wrapping: Plastic or cloth coverings used for protection, moisture control, and flavor development

Natural Rind: Outer layer, often mold-ripened, protecting cheese, influencing flavor, texture, and aging process

The natural rind of a cheese wheel is a living, breathing entity, a protective barrier that shields the delicate interior from the outside world. This outer layer, often mold-ripened, plays a crucial role in the cheese-making process, influencing not only the flavor and texture but also the overall aging process. As the cheese matures, the rind develops a complex ecosystem of microorganisms, including bacteria, yeasts, and molds, which contribute to the unique characteristics of each cheese variety. For instance, the rind of a Camembert cheese is inoculated with *Penicillium camemberti*, a mold that imparts a distinctive earthy flavor and creamy texture to the cheese.

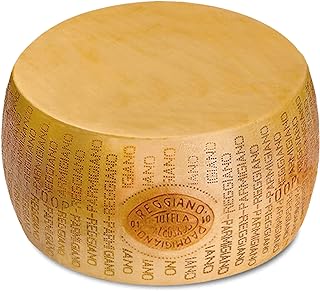

To understand the significance of the natural rind, consider the aging process of a cheese wheel. As the cheese matures, the rind acts as a semipermeable membrane, allowing moisture to evaporate while preventing excessive drying. This delicate balance is critical, as it enables the cheese to develop its characteristic flavor and texture. In the case of hard cheeses like Parmigiano-Reggiano, the rind is brushed with a mixture of salt and oil to create a hard, protective barrier that slows down the aging process, resulting in a dense, granular texture and a sharp, nutty flavor. On the other hand, soft cheeses like Brie have a thinner, more delicate rind that allows for a faster aging process, resulting in a creamy, rich interior and a mild, earthy flavor.

When working with natural-rind cheeses, it's essential to handle them with care to preserve the integrity of the rind and the cheese itself. For example, when cutting a cheese wheel, use a sharp, sterile knife to minimize damage to the rind, and avoid touching the cut surface with your hands to prevent contamination. Additionally, store natural-rind cheeses in a cool, humid environment, such as a cheese cave or a refrigerator with a dedicated cheese drawer, to maintain the optimal conditions for aging. As a general guideline, soft cheeses with natural rinds should be consumed within 2-3 weeks of purchase, while hard cheeses can be aged for several months or even years, depending on the variety.

The flavor and texture of a natural-rind cheese are not only influenced by the rind itself but also by the aging process and the specific microorganisms present. For instance, the rind of a blue cheese like Roquefort is inoculated with *Penicillium roqueforti*, a mold that produces a distinctive blue-green veining and a sharp, pungent flavor. To enhance the flavor of natural-rind cheeses, consider pairing them with complementary foods and beverages. For example, a rich, creamy Brie pairs well with a crisp, acidic white wine, while a sharp, nutty Parmigiano-Reggiano is perfectly complemented by a full-bodied red wine or a drizzle of balsamic vinegar. By understanding the unique characteristics of natural-rind cheeses and how to properly handle and pair them, you can unlock a world of complex flavors and textures that will elevate any culinary experience.

In a comparative analysis, natural-rind cheeses can be contrasted with cheeses that have been treated with wax or other artificial coatings. While these coatings may provide a longer shelf life and a more consistent appearance, they often lack the depth of flavor and complexity that natural-rind cheeses offer. Furthermore, the use of artificial coatings can hinder the aging process, resulting in a less nuanced flavor profile. By choosing natural-rind cheeses, you not only support traditional cheese-making methods but also experience the unique flavors and textures that can only be achieved through a natural aging process. As you explore the world of natural-rind cheeses, remember to experiment with different varieties, aging times, and pairings to discover the vast array of flavors and textures that these cheeses have to offer.

Unveiling the Mystery: Why Babybel Cheese Wears a Red Coat

You may want to see also

Wax Coating: Applied to preserve moisture, prevent mold, and extend shelf life of cheese

A cheese wheel's exterior often features a wax coating, a protective barrier that serves multiple purposes. This layer is not merely decorative; it is a functional shield, meticulously applied to safeguard the cheese within. The art of waxing cheese has been honed over centuries, with modern techniques ensuring optimal preservation.

The Science Behind Wax Coating

Wax acts as an impermeable barrier, effectively sealing the cheese and creating a microenvironment that slows down the aging process. This is particularly crucial for cheeses intended for long-term storage or transportation. The wax coating prevents moisture loss, a critical factor in maintaining the cheese's texture and flavor. As cheese ages, it naturally loses moisture, and without protection, this process can lead to an undesirable dry and crumbly texture. The wax layer also inhibits mold growth, a common issue in humid environments. By creating a physical barrier, it reduces the risk of mold spores settling and proliferating on the cheese's surface.

Application Techniques and Best Practices

Applying wax to a cheese wheel is a precise process. The cheese is typically heated slightly to ensure the wax adheres properly. Food-grade wax, often a blend of paraffin and microcrystalline wax, is melted and applied in thin, even coats. Multiple layers may be necessary to achieve the desired thickness, usually around 1-2 millimeters. It is essential to ensure the wax is free from any contaminants, as impurities can affect the cheese's flavor and safety. After application, the wax hardens, forming a protective shell. This process is especially vital for artisanal cheesemakers who aim to preserve the unique characteristics of their craft.

Benefits and Considerations

The wax coating significantly extends the cheese's shelf life, allowing it to mature gracefully. It is a preferred method for aging hard and semi-hard cheeses, such as Cheddar, Gouda, and Swiss. However, not all cheeses benefit from waxing. Soft and blue-veined cheeses, for instance, require different preservation methods due to their higher moisture content and unique aging processes. Additionally, while wax provides excellent protection, it is not a permanent solution. Over time, the wax can crack, especially if the cheese is subjected to temperature fluctuations. Regular inspection and re-waxing may be necessary for long-term storage.

A Practical Guide for Cheese Enthusiasts

For those aging cheese at home, waxing is a valuable skill. Start by sourcing food-grade wax and a suitable melting pot. Ensure the cheese is at room temperature before application. Brushes or dipping techniques can be employed, depending on the desired finish. After waxing, store the cheese in a cool, dry place, ideally with consistent temperature and humidity levels. Regularly check for any signs of wax deterioration and reapply as needed. This hands-on approach allows cheese enthusiasts to experiment with aging and develop a deeper appreciation for the craft.

In the world of cheese preservation, wax coating stands as a time-tested method, offering a simple yet effective solution to extend the life of this beloved dairy product. Its application is both an art and a science, requiring precision and an understanding of the cheese's unique needs.

Garlic Cheese Sticks: Unveiling the Quantity in a Single Order

You may want to see also

Ash Layer: Thin coating of edible ash, adding earthy flavor and unique appearance to cheese

A thin layer of edible ash on a cheese wheel is not merely decorative; it serves as a functional and sensory enhancer. This technique, rooted in centuries-old cheesemaking traditions, particularly in France, transforms the exterior of cheeses like Morbier and Saint-André into a canvas of flavor and texture. The ash, typically derived from vegetable sources such as vine or wood, is applied as a fine powder or mixed with salt to create a paste. Its primary purpose is to regulate acidity, inhibit unwanted mold growth, and foster the development of desirable bacteria, resulting in a cheese that is both visually striking and culinarily complex.

Applying an ash layer requires precision and care. For home cheesemakers, a common method involves dusting the ash evenly over the cheese’s surface during the first few days of aging. Commercial producers often use a slurry, combining ash with a small amount of water or brine to ensure adherence. The thickness of the layer is crucial: too much can overpower the cheese’s natural flavors, while too little may not achieve the desired effect. A general guideline is to use 1-2 grams of ash per kilogram of cheese, adjusting based on the specific variety and desired intensity. This step is typically performed before the cheese is wrapped or aged further, allowing the ash to interact with the rind as it matures.

The ash layer’s impact extends beyond aesthetics, contributing a distinct earthy, slightly smoky flavor that complements the cheese’s interior. In Morbier, for example, the ash-dusted line running through the center not only adds visual intrigue but also creates a contrast between the milder top layer and the more robust bottom. This interplay of flavors and textures makes ash-coated cheeses particularly appealing to connoisseurs seeking complexity. Pairing suggestions include crusty bread, full-bodied red wines, or even dark honey to balance the ash’s subtle bitterness.

Despite its benefits, working with ash requires caution. Edible ash must be food-grade and free from contaminants, as improper sourcing can pose health risks. Additionally, while the ash itself is safe to consume, some individuals may find its gritty texture unappealing. To mitigate this, cheeses with ash layers are often served with the rind removed, though purists argue that doing so sacrifices the full sensory experience. For those new to ash-coated cheeses, starting with milder varieties like Saint-André can provide a gentler introduction to this unique tradition.

In conclusion, the ash layer on a cheese wheel is a testament to the artistry and science of cheesemaking. It bridges the gap between tradition and innovation, offering both functional benefits and a sensory experience that elevates the cheese to a new level. Whether you’re a seasoned aficionado or a curious newcomer, understanding and appreciating this technique enriches the enjoyment of one of the world’s most beloved foods.

Should You Cover Cheese-Topped Dishes When Baking in the Oven?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Brined Surface: Salt-cured exterior, creating a firm texture and tangy taste, common in feta

A brined surface on a cheese wheel is a testament to the transformative power of salt and moisture. This method, often associated with cheeses like feta, involves submerging the cheese in a saltwater solution, which not only preserves the cheese but also imparts a distinctive firm texture and tangy flavor. The brine acts as a protective barrier, slowing the growth of unwanted bacteria while encouraging the development of beneficial microbes that contribute to the cheese's unique character.

To achieve a brined surface, the process begins with a carefully measured brine solution, typically consisting of water saturated with salt to the point of crystallization (around 20-25% salinity). The cheese is then fully submerged in this solution, where it remains for a period ranging from a few days to several weeks, depending on the desired outcome. For feta, this brining period can last up to two months, during which the cheese absorbs salt and moisture, developing its signature tanginess and crumbly yet firm texture.

One of the key advantages of a brined surface is its ability to extend the cheese's shelf life. The high salt concentration draws moisture out of the cheese, creating an environment inhospitable to spoilage organisms. This makes brined cheeses particularly well-suited for storage and transportation, a trait that has historically made them popular in regions with limited refrigeration. However, it’s crucial to monitor the brine’s salinity and temperature to prevent over-salting or contamination.

For home cheesemakers, replicating a brined surface requires attention to detail. Start by preparing a brine solution using non-iodized salt, as iodine can affect flavor and texture. Submerge the cheese in a food-grade container, ensuring it’s fully covered, and store it in a cool, consistent environment (ideally between 50-55°F). Regularly skim any surface mold from the brine and replace the solution every few weeks to maintain its effectiveness. The result is a cheese with a tangy, salty exterior that contrasts beautifully with its creamy or crumbly interior.

While brined surfaces are most commonly associated with feta, this technique is also used in other cheeses like halloumi and certain types of fresh cheeses. Each cheese benefits uniquely from brining, whether it’s halloumi’s ability to hold its shape when grilled or the refreshing tang of a brined goat cheese. Understanding the brining process allows cheese enthusiasts to experiment with flavors and textures, creating cheeses that are both preserved and enhanced by their salt-cured exteriors.

Measuring Cheese: How Many Ounces Are in a Handful?

You may want to see also

Artificial Wrapping: Plastic or cloth coverings used for protection, moisture control, and flavor development

The exterior of a cheese wheel often features artificial wrapping, a critical yet underappreciated component that serves multiple functions. Plastic and cloth coverings are not merely protective barriers; they are engineered to regulate moisture, shield against contaminants, and even influence flavor development. These materials are selected based on the cheese’s type, age, and desired outcome, making them as much a part of the cheese’s identity as its interior texture and taste.

Consider the role of plastic wrapping, typically made from food-grade polyethylene or polypropylene. These materials create a semi-permeable barrier that allows controlled moisture exchange, essential for cheeses like Cheddar or Gouda that require a drier environment to age properly. For example, a low-density polyethylene wrap with a moisture vapor transmission rate (MVTR) of 50–100 g/m²/day is ideal for semi-hard cheeses, preventing excessive drying while inhibiting mold growth. However, plastic is not without drawbacks; it can trap excess moisture in humid environments, leading to off-flavors or spoilage. Proper storage conditions—such as maintaining a temperature of 50–55°F (10–13°C) and 80–85% humidity—are crucial when using plastic wraps.

Cloth coverings, often treated with wax or paraffin, offer a contrasting approach. Used traditionally for cheeses like clothbound Cheddar or Gruyère, these wraps allow greater breathability, fostering the growth of desirable surface molds and bacteria that contribute to complex flavors. For instance, a cotton cloth soaked in a brine solution and wrapped around a young cheese wheel can introduce salinity and encourage the development of a natural rind. However, cloth requires meticulous handling to avoid contamination. It must be regularly inspected for unwanted mold growth and replaced if necessary, typically every 2–3 weeks during the aging process.

The choice between plastic and cloth ultimately depends on the cheese’s intended profile. Plastic is ideal for consistency and protection, particularly in industrial settings, while cloth is favored for artisanal cheeses where flavor nuance is paramount. Hybrid solutions, such as cheese wrapped in cloth and then encased in a breathable plastic film, are increasingly popular for balancing moisture control and flavor development. Regardless of the material, the wrapping must be applied with precision—too tight, and it restricts airflow; too loose, and it fails to provide adequate protection.

In practice, cheesemakers should experiment with wrapping techniques to achieve their desired outcomes. For plastic, pre-shrinking the wrap by heating it slightly ensures a snug fit without damaging the cheese. For cloth, pre-treating it with a mixture of salt and water can enhance its moisture-regulating properties. Both methods require monitoring, as environmental factors like temperature and humidity can drastically alter their effectiveness. By understanding the science and art of artificial wrapping, cheesemakers can elevate their craft, ensuring each wheel reaches its full potential.

Mastering Vacuum-Sealed Cheese Aging: Techniques for Perfectly Matured Flavors

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The hard outer layer of a cheese wheel is called the rind.

Yes, the rind of many cheese wheels is edible, though it depends on the type of cheese and the rind’s texture.

The outside of a cheese wheel can be coated with materials like wax, cloth, ash, or natural molds, depending on the cheese variety.

Mold on the outside of some cheese wheels is intentional and part of the aging process, contributing to flavor and texture development.