Blue cheese is made by adding mould cultures, such as Penicillium roqueforti, to cow, sheep, or goat milk. The mould creates the distinctive blue-green veins that run through the cheese, giving it its name and its sharp, salty flavour. The mould is activated when exposed to oxygen, which happens when the cheese is pierced to create air tunnels. Blue cheese was likely discovered by accident when cheeses were stored in caves with controlled temperature and moisture levels that happened to be favourable environments for harmless moulds.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| How it's made | Blue cheese is made by adding cultures of edible moulds, such as Penicillium roqueforti, to milk from cows, sheep or goats. |

| Colour | Blue cheese can have blue or green veins or spots. |

| Flavour | Blue cheese varies in flavour from mild to strong, slightly sweet to salty or sharp. |

| Smell | Blue cheese has a distinctive smell, caused by the mould and bacteria. |

| Texture | Blue cheese can vary in texture from liquid to hard. |

| History | Blue cheese was believed to have been discovered by accident when cheeses were stored in caves with naturally controlled temperatures and moisture levels, creating an environment favourable for mould. |

| Health concerns | People who are allergic to penicillin should avoid blue cheese. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Blue cheese is made with the addition of edible moulds

- The moulds create blue-green spots or veins through the cheese

- Blue cheese is believed to have been discovered by accident

- Penicillium roqueforti creates the characteristic blue veins in blue cheese

- Blue cheese is aged in temperature-controlled environments

Blue cheese is made with the addition of edible moulds

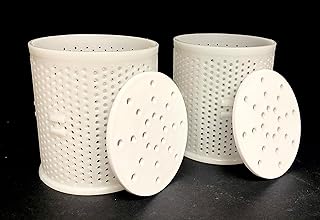

Blue cheese is made by adding edible moulds to milk from cows, sheep, or goats. The mould, Penicillium roqueforti, is added to the milk mixture, which is then incubated for three to four days. Salt and/or sugar are added, and aerobic incubation continues for another one to two days. The mixture is then ladled into containers to drain and form into cheese wheels. The Penicillium roqueforti inoculum is sprinkled on top of the curds, along with Brevibacterium linens, and the curds are then pressed into moulds to form cheese loaves with a relatively open texture.

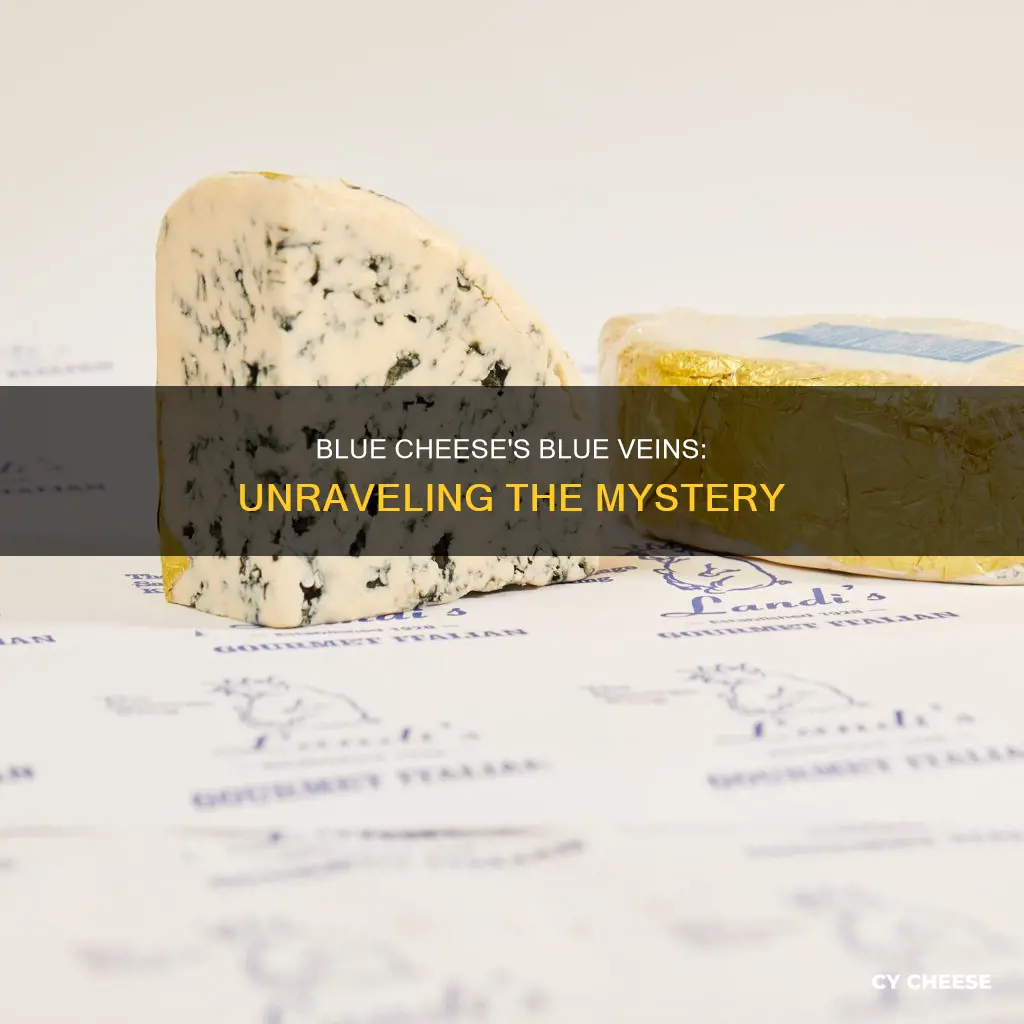

The mould in blue cheese is responsible for its characteristic blue veins. After the cheese has been aged and pierced to form air tunnels, the mould grows along the surface of the curd-air interface, creating blue or blue-green veins throughout the cheese. These veins contribute to the unique flavour and aroma of blue cheese. The piercing of the cheese during the ageing process encourages the growth of the mould and enhances the blue taste.

Blue cheese is believed to have been discovered by accident when cheeses were stored in caves with naturally controlled temperature and moisture levels, creating an environment favourable for the growth of harmless mould. This accidental mould in cheeses can be delicious and is sometimes sought after by customers. The accidental bluing can even transform a non-blue cheese into an entirely different cheese, such as the blue-veined Appleby's Cheshire, also known as "Green Fade".

The mould in blue cheese, Penicillium, is the same type of mould used to make antibiotics like penicillin. While the mould in blue cheese is generally safe to consume, those with allergies to penicillin should avoid it as it may trigger an allergic reaction.

Blue Cheese Buying: Best Places to Purchase

You may want to see also

The moulds create blue-green spots or veins through the cheese

Blue cheese is any cheese made with the addition of cultures of edible mould. The moulds create blue-green spots or veins throughout the cheese. The mould most commonly used is Penicillium roqueforti, which is added to autoclaved, homogenized milk via a sterile solution. The mould is also sometimes Penicillium glaucum, which is related to Penicillium roqueforti.

After the curds have been ladled into containers, the Penicillium roqueforti inoculum is sprinkled on top of the curds along with Brevibacterium linens. The curds are then formed into cheese loaves with a relatively open texture, to allow for air gaps between them. The mould grows along the surface of the curd-air interface. Piercing the cheese and creating air tunnels allows oxygen to reach the mould, which then activates and turns blue or blue-green. This process also adds flavour and changes the texture of the cheese.

The blue veins in the cheese are responsible for its signature sharp and salty flavour, as well as its distinctive smell. The mould, along with certain types of bacteria, gives blue cheese its special aroma. Brevibacterium linens, for example, is the same bacteria behind foot and human body odour.

Blue cheeses vary in flavour, colour, and consistency. They are typically aged in temperature-controlled environments. Blue cheese is believed to have been discovered by accident when cheeses were stored in caves with naturally controlled temperature and moisture levels, which created a favourable environment for harmless mould to grow.

The Bluest of Mild Blues: A Cheese Exploration

You may want to see also

Blue cheese is believed to have been discovered by accident

The mould responsible for the distinctive flavour and appearance of blue cheese is called Penicillium roqueforti. It breaks down the cheese's proteins and fats, releasing flavour compounds that contribute to its pungency, sharpness, and piquant notes. Penicillium roqueforti is not the only mould that can be used to make blue cheese; Penicillium glaucum is another option. However, both of these moulds require the presence of oxygen to grow. Therefore, initial fermentation of the cheese is done by lactic acid bacteria, which are then killed by the low pH, allowing the Penicillium roqueforti to take over and maintain a pH in the aged cheese above 6.0.

To make blue cheese, cheesemakers start with milk from cows, sheep, goats, or even buffalo. This milk may be raw or pasteurized, and the diet of the animals whose milk is used can affect the final product. The milk is then mixed with sterile salt to create a fermentation medium, and a spore-rich Penicillium roqueforti culture is added. Next, modified milk fat is added, stimulating a progressive release of free fatty acids via lipase action, which is essential for rapid flavour development.

Once the cheese has been formed into a wheel, it is pierced with stainless steel needles to create crevices that allow oxygen to interact with the cultures in the cheese and promote the growth of the blue mould. Some blue cheeses are injected with spores before the curds form, while others have spores mixed in with the curds after they form. The cheese is then aged in a cool, humid environment, allowing the mould to grow and develop its distinctive flavour and appearance.

Blue Cheese and Eggs: What's the Connection?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Penicillium roqueforti creates the characteristic blue veins in blue cheese

Blue cheese is any cheese made with the addition of cultures of edible moulds, which create blue-green spots or veins throughout the cheese. These veins give the cheese its name, as well as its signature sharp and salty flavour. Penicillium roqueforti is the specific mould that creates the characteristic blue veins in blue cheese.

The process of making blue cheese involves adding salt, sugar, or both to autoclaved, homogenized milk via a sterile solution. This mixture is then inoculated with Penicillium roqueforti and incubated for three to four days at 21–25 °C (70–77 °F). More salt and/or sugar is added, and then aerobic incubation is continued for an additional one to two days. Alternatively, sterilized, homogenized milk and reconstituted non-fat solids or whey solids can be mixed with sterile salt to create a fermentation medium, to which a spore-rich Penicillium roqueforti culture is added.

Once the cheese curds have been formed, they are ladled into containers to drain and form into wheels. At this point, the Penicillium roqueforti inoculum is sprinkled on top of the curds, along with Brevibacterium linens, a type of bacteria that contributes to the distinct aroma of blue cheese. The curds are then knit into moulds to form cheese loaves with a relatively open texture.

The key step in allowing Penicillium roqueforti to create the blue veins occurs after the cheese has been formed and salted. The cheese is pierced, creating air tunnels in the cheese. When exposed to oxygen, the Penicillium roqueforti mould grows along the surface of the curd-air interface, forming the characteristic blue veins. This piercing process is often done multiple times to encourage a quick and heavy bluing, resulting in a more dominant blue flavour.

Blue cheese is believed to have been discovered by accident, when cheeses were stored in caves with naturally controlled temperature and moisture levels that happened to be favourable environments for the growth of harmless moulds. Today, blue cheese is intentionally produced with Penicillium roqueforti to create the distinctive blue veins that give the cheese its unique flavour and aroma.

Blue Cheese and FODMAP: What's the Lowdown?

You may want to see also

Blue cheese is aged in temperature-controlled environments

Blue cheese is believed to have been discovered by accident when cheeses were stored in caves with naturally controlled temperatures and moisture levels, which happened to be favourable environments for the growth of harmless mould. The mould responsible for the characteristic blue veins in blue cheese is Penicillium roqueforti, which requires oxygen to grow.

Once the cheese curds have been formed into loaves, they are pierced to create air tunnels. When exposed to oxygen, the Penicillium roqueforti mould grows along the surface of the curd-air interface, creating the blue veins. The veins are also responsible for the aroma of blue cheese.

Blue cheese is typically aged in temperature-controlled environments. The optimal maturing temperature for most cheeses is about 50 to 55°F (12 to 15°C). If the temperature is any warmer, the cheese may age too rapidly and could spoil. Colder temperatures prevent spoilage but slow the ageing process dramatically. Some cheeses, such as blue cheese, benefit from a slower, colder ripening period, which allows microbes to alter the cheese without growing too quickly. During the ripening period, the temperature and humidity levels are carefully monitored to ensure the cheese does not spoil and maintains its optimal flavour and texture.

Blue cheese can have blue or green mould, and both are safe to eat. However, it is important to watch out for white, pink, or grey fluffy mould that may grow on the surface of the cheese over time.

Blue Cheese: A Rat Killer or Urban Myth?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The blue in blue cheese is a type of mold called Penicillium roqueforti, which creates the characteristic blue-green veins in the cheese.

Yes, the blue mold in blue cheese is safe to eat and even has health benefits. However, some people with mold allergies may have a reaction to it, so it is important to be cautious if you are allergic.

The blue color in blue cheese is a result of the Penicillium mold reacting with oxygen. When the mold is exposed to oxygen, it activates and turns the white paste blue.

The strong smell of blue cheese is caused by the combination of the mold and certain types of bacteria, such as Brevibacterium linens, which is the same bacteria responsible for foot and body odor.