Cheese, a beloved and versatile dairy product, is a staple in many diets worldwide, but understanding its place within the food groups is essential for balanced nutrition. When considering the food group for cheese, it falls primarily under the Protein Foods Group, as it is derived from milk and provides essential nutrients like protein, calcium, and vitamins. However, cheese also contains significant amounts of fat, which aligns it with the Dairy Group in dietary guidelines, emphasizing its role as a source of calcium and vitamin D. The classification can vary depending on the type of cheese and its nutritional profile, making it important to consume it in moderation as part of a well-rounded diet.

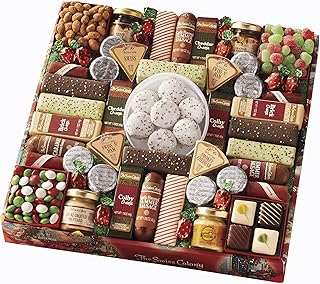

Explore related products

$19.99 $24.99

What You'll Learn

- Cheese Classification: Categorizing cheese by type (hard, soft, blue) and milk source (cow, goat, sheep)

- Nutritional Value: Protein, calcium, fat, and vitamin content in different cheese varieties

- Fermentation Process: Role of bacteria and enzymes in cheese production and flavor development

- Dietary Considerations: Cheese in lactose intolerance, keto, and low-carb diets

- Storage and Pairing: Best practices for storing cheese and ideal food/wine pairings

Cheese Classification: Categorizing cheese by type (hard, soft, blue) and milk source (cow, goat, sheep)

Cheese, a staple in diets worldwide, is classified into various categories based on texture and milk source, each offering distinct flavors and culinary uses. Understanding these classifications—hard, soft, and blue cheeses, alongside cow, goat, and sheep milk origins—empowers both chefs and enthusiasts to make informed choices. For instance, hard cheeses like Parmesan are ideal for grating due to their low moisture content, while soft cheeses such as Brie excel in spreads or desserts. Blue cheeses, with their distinctive veins, add complexity to salads or pairings with sweet accompaniments like honey.

Analyzing milk sources reveals nuanced differences in taste and texture. Cow’s milk cheeses, the most common, range from mild Cheddar to sharp Gruyère, offering versatility for various dishes. Goat’s milk cheeses, like Chevre, present a tangy, lighter profile, making them perfect for salads or pairing with fruit. Sheep’s milk cheeses, such as Manchego, are richer and nuttier, often used in tapas or as standalone indulgences. These variations stem from differences in milk fat content and protein structure, influencing both flavor and consistency.

For practical application, consider pairing hard cheeses with bold wines or using them in pasta dishes for a savory finish. Soft cheeses shine in appetizers or as dessert components, their creamy texture complementing crackers or fresh berries. Blue cheeses, though polarizing, elevate dishes when used sparingly—think crumbled over steak or mixed into dressings. When selecting by milk source, note that goat and sheep cheeses are naturally lower in lactose, making them suitable for those with mild dairy sensitivities.

A comparative approach highlights the interplay between type and milk source. For example, a hard cow’s milk cheese like Pecorino Romano shares the firmness of Parmesan but carries a sheep’s milk richness. Conversely, a soft goat’s milk cheese like Bucheron offers a tangier alternative to cow’s milk Camembert. Blue cheeses, regardless of milk source, share a pungency that divides opinions but unites in versatility—from Roquefort (sheep) to Gorgonzola (cow).

In conclusion, mastering cheese classification enhances culinary creativity and appreciation. By understanding the interplay of texture and milk source, one can tailor selections to specific dishes or dietary needs. Whether crafting a cheese board or experimenting in the kitchen, this knowledge transforms cheese from a simple ingredient into a sophisticated element of flavor and texture.

Cheese Wedges Per Pound: A Guide to Portioning Cheese

You may want to see also

Nutritional Value: Protein, calcium, fat, and vitamin content in different cheese varieties

Cheese, a staple in many diets worldwide, is a nutrient-dense food that belongs to the dairy group. Its nutritional profile varies widely depending on the type, making it essential to understand the differences to make informed dietary choices. From protein and calcium to fat and vitamin content, each cheese variety offers unique benefits and considerations.

Analyzing Protein Content: A Muscle-Building Perspective

Protein is a cornerstone of cheese’s nutritional value, with harder varieties like Parmesan (41g per 100g) and Gruyère (29g per 100g) leading the pack. These options are ideal for individuals aiming to increase protein intake without consuming large portions. Softer cheeses like Brie (21g per 100g) or cream cheese (6g per 100g) provide less protein but can still contribute to daily needs. For athletes or older adults, pairing high-protein cheeses with lean meats or plant-based proteins ensures a balanced intake. A 30g serving of Parmesan, for instance, delivers 12g of protein, nearly 25% of the daily requirement for an average adult.

Calcium Variations: Bone Health Across Ages

Cheese is a calcium powerhouse, crucial for bone density and muscle function. Hard cheeses like Cheddar (721mg per 100g) and Swiss (741mg per 100g) provide more calcium per serving than softer varieties like mozzarella (578mg per 100g). For children aged 9–18, who need 1,300mg of calcium daily, a 30g serving of Swiss cheese contributes 222mg, making it an excellent snack option. Pregnant women and postmenopausal adults, who require 1,000–1,200mg daily, can benefit from incorporating harder cheeses into meals. However, those with lactose intolerance should opt for aged cheeses like Parmesan, which contain minimal lactose while retaining high calcium levels.

Fat Content: Navigating Saturated Fats and Health

Fat content in cheese varies significantly, with full-fat options like Blue Cheese (35g per 100g) and Goat Cheese (21g per 100g) containing higher levels of saturated fats. While fat contributes to flavor and satiety, excessive saturated fat intake is linked to cardiovascular risks. Low-fat alternatives like part-skim mozzarella (17g per 100g) or cottage cheese (4g per 100g) offer a healthier profile without sacrificing taste. For heart-conscious individuals, limiting portions to 30–50g per serving and pairing cheese with fiber-rich foods like whole-grain crackers can mitigate potential risks. The American Heart Association recommends keeping saturated fat intake below 13g daily, making portion control key.

Vitamin Contributions: Beyond the Basics

Cheese is a notable source of vitamins, particularly vitamin B12, essential for nerve function and DNA synthesis, and vitamin A, vital for immune health and vision. Aged cheeses like Gouda (3.3µg of B12 per 100g) and Cheddar (1.4µg per 100g) provide substantial B12, while soft cheeses like Camembert (280µg of vitamin A per 100g) are rich in vitamin A. For vegans or those with dietary restrictions, cheese can be a reliable alternative to meat or fish for B12 intake. However, it’s important to note that cheese is not a significant source of vitamin D or C, so pairing it with fortified foods or fruits can create a more rounded nutrient profile.

Practical Tips for Maximizing Cheese’s Nutritional Value

To harness cheese’s benefits, consider these actionable steps: opt for harder, aged cheeses for higher protein and calcium; choose low-fat varieties for heart health; and pair cheese with nutrient-dense foods like nuts, fruits, or vegetables. For example, a snack of apple slices with 30g of Cheddar combines fiber, antioxidants, and calcium. Always check labels for sodium content, as processed cheeses often contain higher levels. Moderation is key—enjoy cheese as part of a balanced diet rather than a standalone solution. By understanding the nutritional nuances of different varieties, you can make cheese a valuable addition to your meals.

Timing Salt Addition in Cheese Ripening: A Crucial Step Explained

You may want to see also

Fermentation Process: Role of bacteria and enzymes in cheese production and flavor development

Cheese, a staple in many diets, belongs to the dairy food group, renowned for its rich nutritional profile and versatility. However, its transformation from milk to cheese is a complex process driven by fermentation, where bacteria and enzymes play pivotal roles. Understanding this process not only highlights the science behind cheese production but also explains the diverse flavors and textures that make each variety unique.

The fermentation process begins with the introduction of specific bacteria cultures into milk. These bacteria, such as *Lactococcus lactis* and *Streptococcus thermophilus*, convert lactose (milk sugar) into lactic acid. This acidification lowers the milk’s pH, causing it to curdle and separate into curds (solids) and whey (liquid). The type and amount of bacteria used dictate the cheese’s acidity, texture, and initial flavor profile. For example, cheddar relies on *Lactococcus lactis* subsp. *lactis*, while Swiss cheese uses *Streptococcus thermophilus* for its characteristic eye formation. Dosage matters: a 1-2% inoculation rate of bacterial culture per volume of milk is typical, but variations can lead to distinct outcomes.

Enzymes, particularly rennet, further refine the fermentation process. Derived from animal sources or produced through microbial fermentation, rennet contains chymosin, an enzyme that coagulates milk proteins (casein) into a firmer curd. This step is crucial for cheeses like Parmesan or Gouda, where a strong curd structure is essential. However, not all cheeses require rennet; some, like cottage cheese, rely solely on bacterial acidification. The timing and dosage of enzyme addition are critical—too much rennet can lead to a bitter taste, while too little results in a weak curd. A standard dosage is 0.02-0.05% of rennet to milk volume, adjusted based on the desired cheese type.

As cheese ages, secondary bacteria and molds contribute to flavor development. For instance, *Penicillium camemberti* in Camembert or *Penicillium roqueforti* in blue cheese create distinct flavors through proteolysis (protein breakdown) and lipolysis (fat breakdown). These processes release amino acids, fatty acids, and other compounds that give aged cheeses their complex, nuanced tastes. Temperature and humidity control during aging are vital; a slight deviation can alter bacterial activity, impacting flavor. For home cheesemakers, maintaining a consistent 50-55°F (10-13°C) and 85-90% humidity is key for optimal flavor development.

In summary, the fermentation process in cheese production is a delicate interplay of bacteria and enzymes, each contributing to texture, flavor, and structure. From the initial acidification by lactic acid bacteria to the enzymatic action of rennet and the transformative role of aging cultures, every step is a testament to the precision required in cheesemaking. By understanding these mechanisms, one can appreciate the artistry behind cheese and even experiment with crafting unique varieties at home.

Finding Cheese Whiz: A Guide to Its Grocery Store Location

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Dietary Considerations: Cheese in lactose intolerance, keto, and low-carb diets

Cheese, a dairy product, is often scrutinized in diets due to its lactose and carbohydrate content. However, its role varies significantly across dietary restrictions, particularly in lactose intolerance, keto, and low-carb diets. Understanding its composition and impact is crucial for tailored consumption.

For individuals with lactose intolerance, cheese can be both a friend and a foe. Hard cheeses like cheddar, Swiss, and Parmesan contain minimal lactose (less than 1 gram per ounce) due to the fermentation process, which breaks down most of the sugar. Soft cheeses like ricotta or cream cheese, however, retain higher lactose levels and may trigger discomfort. A practical tip is to start with small portions of hard cheese and monitor tolerance. Pairing cheese with lactase enzymes or opting for lactose-free varieties can further alleviate symptoms. Age plays a role here; older adults with age-related lactase deficiency may need stricter portion control.

In keto and low-carb diets, cheese is a staple due to its high fat and protein content, with minimal carbs (typically 0.5–2 grams per ounce). For keto dieters aiming for 20–50 grams of carbs daily, cheese fits seamlessly. However, portion control is key; excessive consumption can lead to calorie surplus, hindering weight loss. Opt for full-fat, unprocessed varieties like mozzarella, gouda, or blue cheese to maximize satiety and nutritional value. A cautionary note: processed cheese products often contain added carbs and preservatives, making them less ideal.

Comparatively, while cheese aligns well with keto and low-carb goals, its sodium content warrants attention. A single ounce of cheddar provides roughly 170 mg of sodium, contributing to daily intake limits (2,300 mg recommended). Those with hypertension or sodium sensitivity should balance cheese consumption with low-sodium foods. Additionally, pairing cheese with fiber-rich vegetables or nuts can enhance digestion and nutrient absorption, a strategy particularly beneficial for low-carb dieters.

In conclusion, cheese’s role in dietary considerations is nuanced. For lactose intolerance, hard cheeses in moderation offer a safe option. In keto and low-carb diets, it’s a versatile, nutrient-dense choice but requires mindful portioning and variety selection. By understanding these specifics, individuals can integrate cheese effectively into their dietary plans without compromising health goals.

Is 'He's the Big Cheese' an Idiom or Metaphor?

You may want to see also

Storage and Pairing: Best practices for storing cheese and ideal food/wine pairings

Cheese, a cornerstone of the dairy group, demands thoughtful storage to preserve its flavor and texture. Optimal conditions hinge on humidity and temperature. Hard cheeses like Parmesan thrive in cooler environments (35°F–40°F), wrapped in wax paper to breathe, while soft cheeses such as Brie require higher humidity (around 50°F) and should be stored in their original packaging until use. Semi-soft varieties like cheddar fall in between, benefiting from refrigeration at 45°F–50°F and rewrapping in parchment after opening. Always avoid plastic wrap, which traps moisture and accelerates spoilage.

Pairing cheese with wine elevates both, but the art lies in balancing intensity. Bold, aged cheeses like Gouda or sharp cheddar pair seamlessly with full-bodied reds such as Cabernet Sauvignon, their richness mirroring the wine’s tannins. Conversely, delicate cheeses like fresh mozzarella or chèvre shine alongside crisp whites like Sauvignon Blanc or sparkling wines, which cut through their mildness without overwhelming them. For blue cheeses, dessert wines like Port or late-harvest Riesling offer a sweet contrast that complements their pungency.

Beyond wine, cheese pairings extend to nuts, fruits, and charcuterie. Hard, nutty cheeses like Gruyère find harmony with toasted almonds or walnuts, enhancing their earthy undertones. Creamy cheeses such as Camembert pair beautifully with tart apples or pears, while salty, cured meats like prosciutto offset the richness of semi-soft cheeses like Havarti. For a playful twist, drizzle honey over blue cheese to temper its sharpness or pair aged cheddar with a tangy chutney for a savory-sweet interplay.

Practical storage tips ensure longevity. Always store cheese in the least cold part of the refrigerator, such as the vegetable drawer, to prevent drying. For longer preservation, freeze hard cheeses in portions, though texture may slightly alter. Label leftovers with dates to track freshness, and let cheese sit at room temperature for 30–60 minutes before serving to unlock its full flavor profile. By mastering storage and pairing, you transform cheese from a simple ingredient into a centerpiece of culinary delight.

Pairing Perfection: Bread and Cheese Combos You Can’t Resist

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Cheese belongs to the Protein Foods Group in the USDA MyPlate guidelines, as it is a good source of protein.

Yes, cheese is also classified under the Dairy Group because it is made from milk and provides similar nutrients like calcium.

Cheese is included in the protein food group because it is a rich source of high-quality protein, essential amino acids, and other nutrients.

Yes, cheese can be part of a balanced diet when consumed in moderation, as it provides protein, calcium, and vitamins but is also high in fat and sodium.

Yes, the classification of cheese can vary by country. For example, in some dietary guidelines, it is primarily grouped under dairy, while others emphasize its protein content.