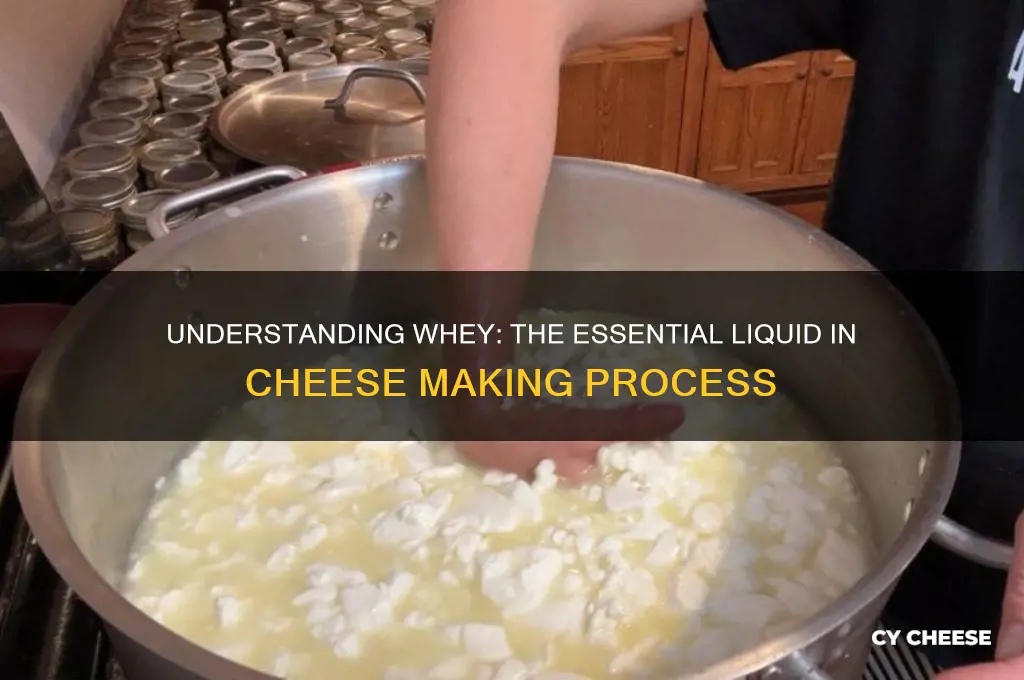

The liquid part of the cheese-making process, known as whey, is a byproduct that plays a crucial role in the transformation of milk into cheese. During the initial stages, rennet or acid is added to milk, causing it to curdle and separate into solid curds and liquid whey. While the curds are further processed into cheese, whey is often collected and utilized for its nutritional value, containing proteins, lactose, vitamins, and minerals. This versatile liquid is not only a staple in various food products but also finds applications in animal feed and even as a base for biogas production, making it an essential yet often overlooked component of cheese production.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Name | Whey |

| Definition | The liquid byproduct of the cheese-making process, separated from the curds. |

| Composition | Primarily water, lactose, proteins (e.g., whey protein, immunoglobulins), vitamins (B-complex, vitamin C), and minerals (calcium, potassium, phosphorus). |

| Types | Sweet whey (from rennet-coagulated cheese), Acid whey (from acid-coagulated cheese like cottage cheese or Greek yogurt). |

| Appearance | Thin, milky liquid, often slightly yellowish or translucent. |

| Taste | Mildly sweet or tangy, depending on the type. |

| Uses | Food ingredient (e.g., protein powders, baked goods), animal feed, dietary supplements, and wastewater treatment. |

| Nutritional Value | Low in fat, high in protein, and rich in essential nutrients. |

| pH Level | Typically ranges from 4.5 to 6.5, depending on the cheese type. |

| Volume Produced | Approximately 9-10 liters of whey per 1 kilogram of cheese produced. |

| Environmental Impact | Historically considered waste, but now increasingly utilized to reduce environmental impact. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Curdling Milk: Acid or rennet is added to milk to separate curds from whey

- Cutting Curds: Curds are cut into smaller pieces to release more whey

- Heating Whey: Whey is heated to shrink curds and expel more liquid

- Draining Whey: Excess whey is drained off, leaving behind the curds

- Pressing Curds: Curds are pressed to remove remaining whey for firmer cheese

Curdling Milk: Acid or rennet is added to milk to separate curds from whey

Curdling milk is a pivotal step in cheese making, where the liquid milk transforms into solid curds and watery whey. This process relies on the addition of acid or rennet, each triggering a distinct biochemical reaction. Acidification, often achieved with vinegar, lemon juice, or cultured buttermilk, lowers the milk’s pH, causing casein proteins to lose their charge and clump together. Rennet, on the other hand, contains enzymes that cleave kappa-casein, destabilizing the protein matrix and allowing curds to form. The choice between acid and rennet depends on the desired cheese type; acid-coagulated cheeses like cottage cheese or queso fresco are softer and simpler, while rennet-coagulated cheeses like cheddar or Parmesan develop firmer textures and complex flavors.

To curdle milk effectively, precision in dosage and timing is critical. For acid coagulation, a general rule is 1–2 tablespoons of vinegar or lemon juice per gallon of milk, added gradually while stirring gently. The milk should curdle within 5–10 minutes at room temperature, with visible separation of curds and whey. Rennet requires more careful measurement; typically, 1/4 teaspoon of liquid rennet diluted in 1/4 cup of cool water is sufficient for 2 gallons of milk. After adding rennet, the milk should set within 30–60 minutes, depending on temperature and milk type. Over-acidifying or using too much rennet can result in tough, rubbery curds, so monitoring the process closely is essential.

The curdling process is not just about separation but also about controlling texture and flavor. Acid-coagulated cheeses tend to have a tangy, fresh taste due to the lactic acid produced during curdling. Rennet-coagulated cheeses, however, retain more sweetness and develop deeper flavors during aging. For example, a hard cheese like Gruyère relies on rennet for its smooth, melt-in-your-mouth texture, while a soft cheese like ricotta uses acid for its crumbly, delicate structure. Understanding these differences allows cheesemakers to tailor the curdling method to the final product’s characteristics.

Practical tips for curdling milk include using fresh, high-quality milk for better results, as ultra-pasteurized milk may not curdle effectively. Maintaining a consistent temperature—around 86°F (30°C) for rennet and room temperature for acid—ensures optimal enzyme activity. After curdling, allowing the curds to rest for 5–10 minutes before cutting or draining improves their firmness. For beginners, starting with acid-coagulated cheeses like paneer or queso blanco offers a forgiving introduction to the process, while experimenting with rennet in simple cheeses like mozzarella builds confidence in handling more complex techniques. Mastery of curdling milk is the foundation of cheese making, unlocking endless possibilities for crafting unique and delicious cheeses.

Cheesecloth Method: Perfectly Warming Up Your Turkey Every Time

You may want to see also

Cutting Curds: Curds are cut into smaller pieces to release more whey

The curd-cutting step in cheese making is a pivotal moment that transforms a gelatinous mass into the foundation of your future cheese. Imagine a vat of warm, coagulated milk – this is your curd. Cutting it isn't just about aesthetics; it's a strategic move to expel whey, the liquid byproduct of cheese making.

Think of it like squeezing water from a sponge. The smaller the sponge pieces, the more water you release. Similarly, cutting curds into smaller pieces increases their surface area, allowing more whey to drain. This whey removal is crucial for several reasons. Firstly, it concentrates the milk solids, intensifying the cheese's flavor and texture. Secondly, it helps control moisture content, influencing the final cheese's hardness and shelf life.

A cheese maker's tool of choice for this task is often a long-bladed knife or a curd cutter, a specialized tool with multiple wires for efficient slicing. The size of the cuts depends on the desired cheese type. For example, cheddar curds are cut into pea-sized pieces, while mozzarella curds are left in larger chunks for a stretchier texture.

The art of curd cutting requires precision and timing. Cutting too early can result in a crumbly, dry cheese, while delaying the process might lead to a softer, more moist variety. The curds should be firm enough to hold their shape when cut but still release whey readily. This delicate balance is achieved through careful monitoring of the curd's texture and the rate of whey expulsion.

This step is a testament to the intricate science behind cheese making. By manipulating the curd's structure, cheese makers can control the final product's characteristics, from the creamy smoothness of Brie to the sharp bite of aged cheddar. Cutting curds is not merely a mechanical process; it's a crucial decision point that shapes the cheese's identity.

Perfect Cheesecake Every Time: Tips to Prevent Cracks and Splits

You may want to see also

Heating Whey: Whey is heated to shrink curds and expel more liquid

Whey, the liquid byproduct of cheese making, undergoes a transformative process when heated, playing a pivotal role in curd development. This step, often overlooked, is crucial for achieving the desired texture and moisture content in the final cheese product. By applying heat, typically between 50°C to 60°C (122°F to 140°F), the whey causes the curds to shrink, expelling excess liquid and tightening their structure. This process not only concentrates the curds but also enhances the overall consistency of the cheese, ensuring it is neither too moist nor too dry.

The science behind heating whey lies in its ability to alter the curd’s protein matrix. As whey temperature rises, the curds contract, forcing out whey moisture through syneresis—a natural process where liquid separates from solids. This step is particularly vital in hard and semi-hard cheese production, such as Cheddar or Gouda, where a firmer texture is desired. For example, in Cheddar making, whey is heated to around 39°C to 43°C (102°F to 109°F) during the cheddaring process, further expelling liquid and creating a dense, sliceable cheese.

From a practical standpoint, heating whey requires precision to avoid overcooking the curds. Home cheesemakers should monitor the temperature closely, using a dairy thermometer for accuracy. Stirring the mixture gently during heating ensures even distribution of heat, preventing localized overheating. It’s also essential to note that the duration of heating varies by cheese type; for instance, soft cheeses like mozzarella may require shorter heating times to maintain their pliable texture.

Comparatively, this step distinguishes traditional cheese making from modern, expedited methods. While some industrial processes bypass prolonged heating, artisanal cheesemakers often emphasize this stage to develop deeper flavors and better texture. The slow, controlled heating of whey allows for the retention of beneficial whey proteins and lactose, contributing to the cheese’s nutritional profile and taste complexity.

In conclusion, heating whey is a nuanced yet indispensable part of cheese making. It bridges the gap between liquid and solid, transforming whey from a mere byproduct into a catalyst for curd perfection. Whether crafting a hard cheese or a soft variety, mastering this technique ensures the final product meets both culinary and sensory expectations. By understanding and applying this process, cheesemakers can elevate their craft, creating cheeses that are not only visually appealing but also rich in flavor and texture.

Syns in Tayto Cheese and Onion Crisps: A Slimming World Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Draining Whey: Excess whey is drained off, leaving behind the curds

The liquid part of the cheese-making process, known as whey, is a byproduct of curdling milk. After coagulation, the milk separates into solid curds and liquid whey. This separation is a critical step, as whey contains lactose, vitamins, and minerals, but it’s the curds that form the foundation of cheese. Draining whey is not merely a removal process; it’s a precise technique that influences the final texture, moisture content, and flavor of the cheese. Too much whey left behind can result in a soft, spreadable cheese like ricotta, while thorough draining yields firmer varieties such as cheddar or parmesan.

Steps to Drain Whey Effectively:

- Gather Tools: Use a fine-mesh strainer or cheesecloth to catch curds while allowing whey to pass through. For larger batches, a cheese press with a whey collection tray is ideal.

- Timing Matters: After cutting the curd, let it rest for 5–10 minutes to release whey naturally. Gentle stirring during this phase encourages even drainage.

- Apply Pressure: For harder cheeses, place the curds in a mold lined with cheesecloth and press gradually. Start with 10–15 pounds of pressure for 15 minutes, then increase to 30–40 pounds for 1–2 hours, depending on the recipe.

Cautions to Consider:

Over-draining can lead to dry, crumbly curds, while under-draining results in a rubbery texture. Monitor the process closely, especially when making mozzarella or halloumi, where moisture balance is critical. Avoid using heat to speed up drainage, as it can toughen the curds. Instead, rely on gravity and controlled pressure.

Practical Tips for Home Cheesemakers:

Save the drained whey—it’s a versatile ingredient rich in protein. Use it as a substitute for water in bread recipes, ferment it into beverages like kefir, or feed it to animals. For small-scale cheese making, tilt the strainer slightly to encourage faster drainage. If using a press, wrap the curds in cheesecloth to prevent them from sticking to the mold.

Takeaway:

Draining whey is both an art and a science. It requires attention to detail, patience, and an understanding of how moisture affects cheese structure. Master this step, and you’ll gain greater control over the final product, whether crafting a creamy camembert or a sharp, aged cheddar.

Cheese Measurement Guide: Ounces in 1 Tablespoon Explained

You may want to see also

Pressing Curds: Curds are pressed to remove remaining whey for firmer cheese

The liquid part of the cheese-making process, known as whey, is a byproduct of curdling milk. After coagulation, the milk separates into solid curds and liquid whey. While whey is often discarded or used in other products, its removal is crucial for determining the texture and firmness of the final cheese. Pressing curds to expel remaining whey is a pivotal step in this transformation, marking the difference between a soft, spreadable cheese and a hard, sliceable one.

Analytical Perspective:

Pressing curds is a mechanical process that applies controlled pressure to squeeze out whey, concentrating the curds into a denser mass. The force applied and duration of pressing directly influence the cheese’s moisture content. For example, cheddar curds are pressed under 50–100 pounds of pressure for several hours, reducing whey content to 35–40% of the cheese’s weight. In contrast, mozzarella curds are lightly pressed to retain more moisture, resulting in its characteristic stretchiness. This step is not merely about removal but about precision—too little pressure yields a crumbly texture, while too much can expel beneficial fats and proteins.

Instructive Approach:

To press curds effectively, start by placing them in a cheese mold lined with cheesecloth. Apply weight gradually, beginning with 5–10 pounds for softer cheeses like Monterey Jack, and increasing to 50 pounds or more for harder varieties like Parmesan. Use a follower (a flat, weighted plate) to distribute pressure evenly. Press in stages, increasing weight every 30–60 minutes, and flip the curd block periodically to ensure uniform moisture removal. For home cheesemakers, a simple setup with bricks or canned goods as weights works well. Monitor the whey runoff—it should slow to a trickle before pressing is complete.

Comparative Insight:

Unlike other moisture-removal methods, such as heating or draining, pressing offers greater control over texture. For instance, ricotta skips pressing entirely, relying on natural drainage to retain its grainy, moist consistency. In contrast, Gruyère undergoes intense pressing, reducing whey to less than 30% of its weight, which contributes to its dense, crystalline structure. Pressing also differs from salting, which draws out moisture osmotically. While salting affects flavor and preservation, pressing directly shapes the cheese’s physical properties, making it a critical step for harder varieties.

Descriptive Takeaway:

Imagine the curds as a sponge saturated with whey. Pressing wrings them out, transforming a soft, pliable mass into a firm, cohesive wheel. The process is both art and science, requiring intuition to gauge when the curds have released enough whey without becoming dry or brittle. The result is a cheese with a texture tailored to its intended use—whether melted over pasta, grated onto salads, or aged for years in a cellar. Mastery of this step elevates cheese from a simple dairy product to a crafted delicacy.

Finding Nacho Cheese at Target: A Quick Aisle-by-Aisle Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The liquid part of the cheese-making process is called whey. It is the watery byproduct that separates from the curds during coagulation.

Whey is not always discarded; it is often used in various products such as protein supplements, animal feed, and even in making ricotta cheese.

Whey plays a crucial role in cheese making by separating from the curds, allowing the solid part (curds) to be further processed into cheese. It also helps in determining the moisture content and texture of the final cheese product.